Octogenarian Majorie Carter, who competed in the 1952 and 1960 Games, has now bagged the top prize of an Inspirational Generation competition.

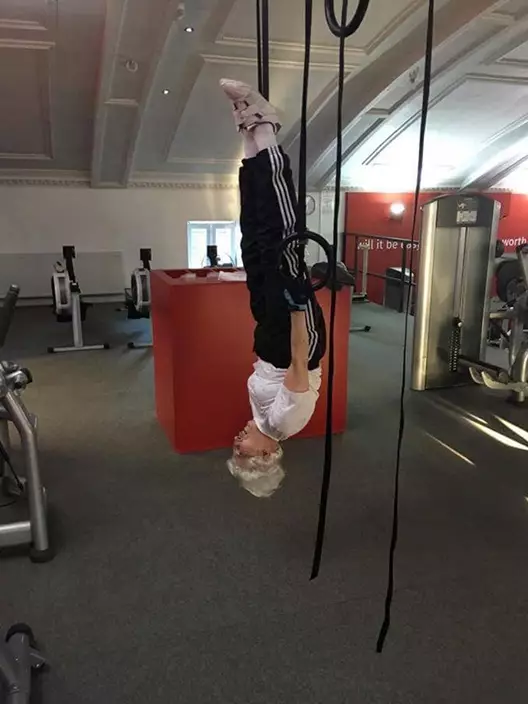

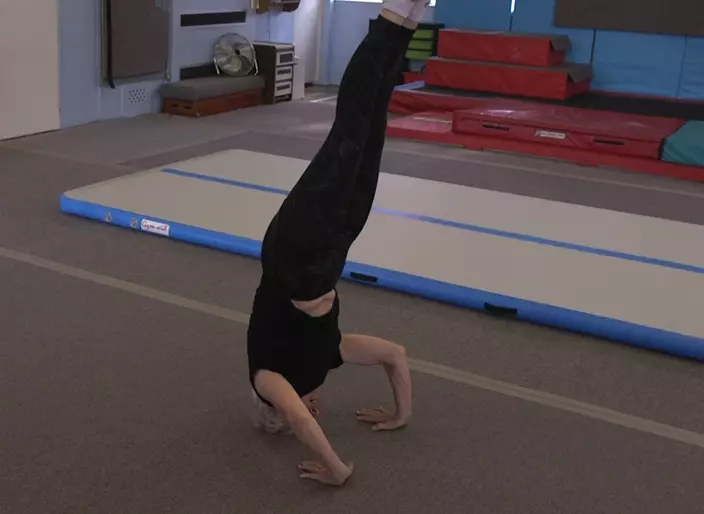

A former athlete, who competed in the Olympics twice, is still performing gravity-defying gymnastic routines at the grand old age of 84.

Age is no barrier for amazing Majorie Carter, a member of the British gymnastics squad at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, and the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Italy – just missing out on medals at both.

The octogenarian, who went on to have an impressive coaching career, nurturing the next generation of gymnasts, still trains three times a week – hitting the gym at 6 am.

Majorie, who lives in a McCarthy & Stone retirement property just outside Bradford, West Yorkshire, said: “I still make sure I train now – I’ve never, ever stopped.

“You need to keep as healthy as you can to live longer. It’s particularly important for older people to help maintain that independence and mobility.

“As they say, ‘use it or you lose it.’”

PA Photo

Grandmother-of-five Majorie, who has been married to her husband Geoffrey, 87, a former photo technician, for 61 years, told how her earliest memory of gymnastics was watching a display at a local cricket field when she was around nine.

Immediately taken by the sport, she decided to give it a try and signed up for weekly classes.

“I’d go every Thursday, and took to it right away,” she said.

PA Photo

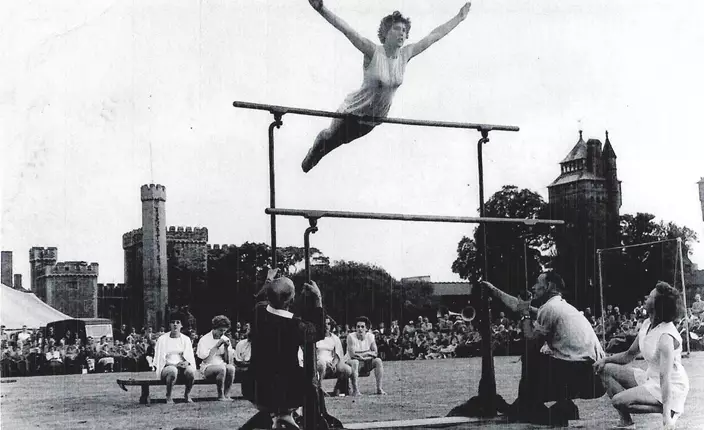

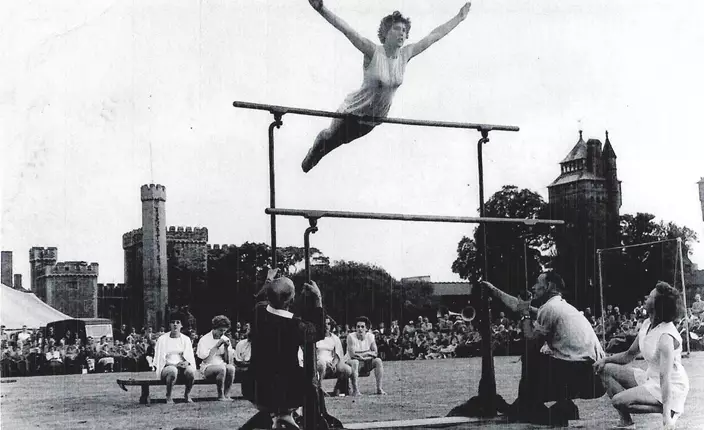

In time, Majorie found herself a coach – Edith Pollard, known as Carrie, who had herself competed in the 1928 Olympic games, then as Edith Pickles, where she and her team won the bronze medal.

As she progressed, Majorie began competing regularly in regional competitions, winning her first title – Yorkshire novice champion – when she was around 16.

“There wasn’t all the funding back then, like there is now, so I was also working full time in a mill to make money to travel to competitions,” she said. “I’d then train in the evenings.”

PA Photo

She added: “I helped to train the younger members of the club I was in and would take them to competitions all over the country.”

Eventually reaching the top of her game, Majorie – mum to Andrew, 56, and Elaine, 53 – was selected to represent her country at the 1952 Olympics, competing for inflow, beam, bars and vault events.

Before heading off to Helsinki, where the Games were held, she and her team-mates were invited to Buckingham Palace to meet Queen Elizabeth, who had only just been crowned.

PA Photo

Majorie recalled: “I was so excited, it was absolutely wonderful. The Queen and Prince Philip mingled and chatted with us all.

“They asked us all about our training and injuries we sustained while practicing.”

Arriving in Helsinki, the Finnish capital, a short while later, Majorie said the atmosphere was electric.

PA Photo

She continued: “Being there was exhilarating, it was such an honor to represent my country. Those memories of the opening ceremony will last a lifetime.

“There was no funding, so we’d paid for our own uniforms, which we wore when we were out together or being interviewed.

“It was a grey skirt, white blouse, grey bag and white shoes – eight girls, eight different shades of grey and styles of shoe.”

PA Photo

She added: “We’d had to work incredibly hard to afford to be there, so it’s wonderful to see all the funding now. It helps give that level playing field, and ensures athletes can focus on their sport.”

Stepping up to compete, Majorie recalls adrenaline coursing through her – together with a determination to show the judges what she could do.

Although her team did not make it to the medals table, she still feels immense pride at making the Games and for the support, the gymnasts gave to each other.

PA Photo

Then, eight years later, she was selected to compete for her country once again, this time at the 1960 Games in Rome.

“We met so many incredible people there. I actually saw Muhammad Ali, who back then was known as Cassius Clay, with his gold medal,” she fondly recalled.

Having put off starting a family until after the Olympics, Majorie fell pregnant in early 1961, welcoming Andrew into the world in November of that same year.

PA Photo

But being a mum didn’t slow her down.

In fact, just 10 months after her son’s birth, she was competing in the British Championships, eventually placing fourth.

Three years later in October 1964, she had her daughter, Elaine, moving into a coaching role for Leeds Athletic Institute shortly after.

PA Photo

“I was coaching part time for 16 hours a week, so it worked out well with the children,” she said.

Since then, Majorie has carved an impressive career as a coach, organizing competitions, choreographing complex routines and nurturing young talent.

Some of her happiest memories are of taking her students to World Gymnaestrada events – a large-scale gymnastics exhibition held every four years, like the Olympics – where the focus is on showcasing rather than winning medals.

PA Photo

“As a coach, you can only get a few to the top for the Olympics,” she said. “But the gymnaestradas are a wonderful chance to perform for everybody.

“It’s organized with a real opening ceremony and it’s lovely to see the students’ faces and how thrilled they are to be there.”

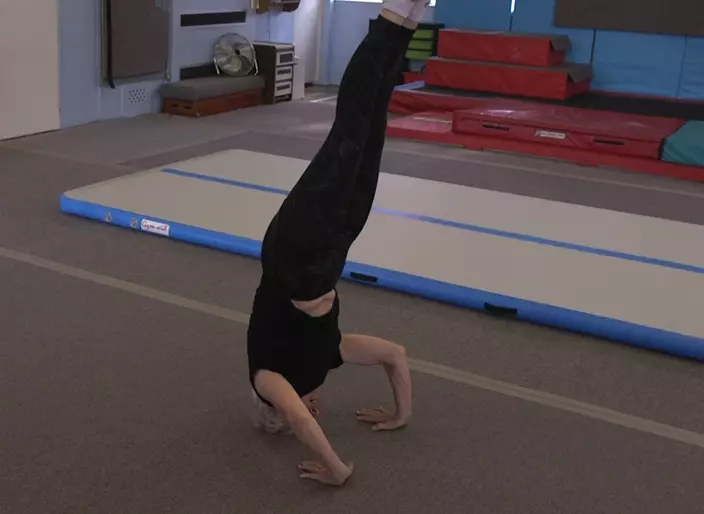

Since retiring eight years ago, Majorie has still been coaching as a volunteer for 12 hours per week.

PA Photo

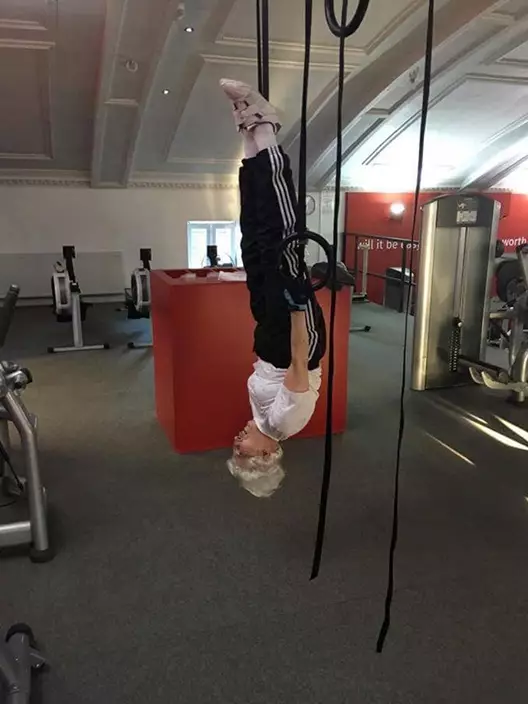

And, keen to ensure she maintains her own fitness, she continues to train and can still do handstands and the splits.

Recently, her incredible feat has been recognized by leading retirement property builders McCarthy & Stone, who, after a nationwide search, crowned her Most Inspirational Older Person 2018.

Speaking of the moment she discovered she’d won the competition, Majorie said: “I found out about the Inspirational Generation competition via a leaflet through the door, and my McCarthy & Stone house manager encouraged me to enter.”

PA Photo

She continued: “I didn’t think I’d win, so I was absolutely overwhelmed to get that congratulations call around two weeks ago.

“I had to take a minute to come to terms with it all.

“It’s been a true honor, and I’ve had a really wonderful life.”

PA Photo

Sharon Gill from McCarthy & Stone, said: “Our Inspirational Generation campaign was focused on raising awareness of the fantastic achievements of those over 60 and how inspirational they are to the younger generation.

“We are delighted for Marjorie, as soon as we saw her entry it was clear she was an exceptionally inspirational lady. She has had a fascinating sporting career and we are delighted to see her recognized in this way, which is what she really deserves.

“Many people see old age as something to dread, and there are lots of negative stereotypes in the media about growing older. Marjorie, like many of our homeowners we see every day, is proving that age is no barrier. It’s just a number and we want to encourage more people to be inspired by Marjorie’s story, and see their retirement as an opportunity – an opportunity to live life to the fullest.”

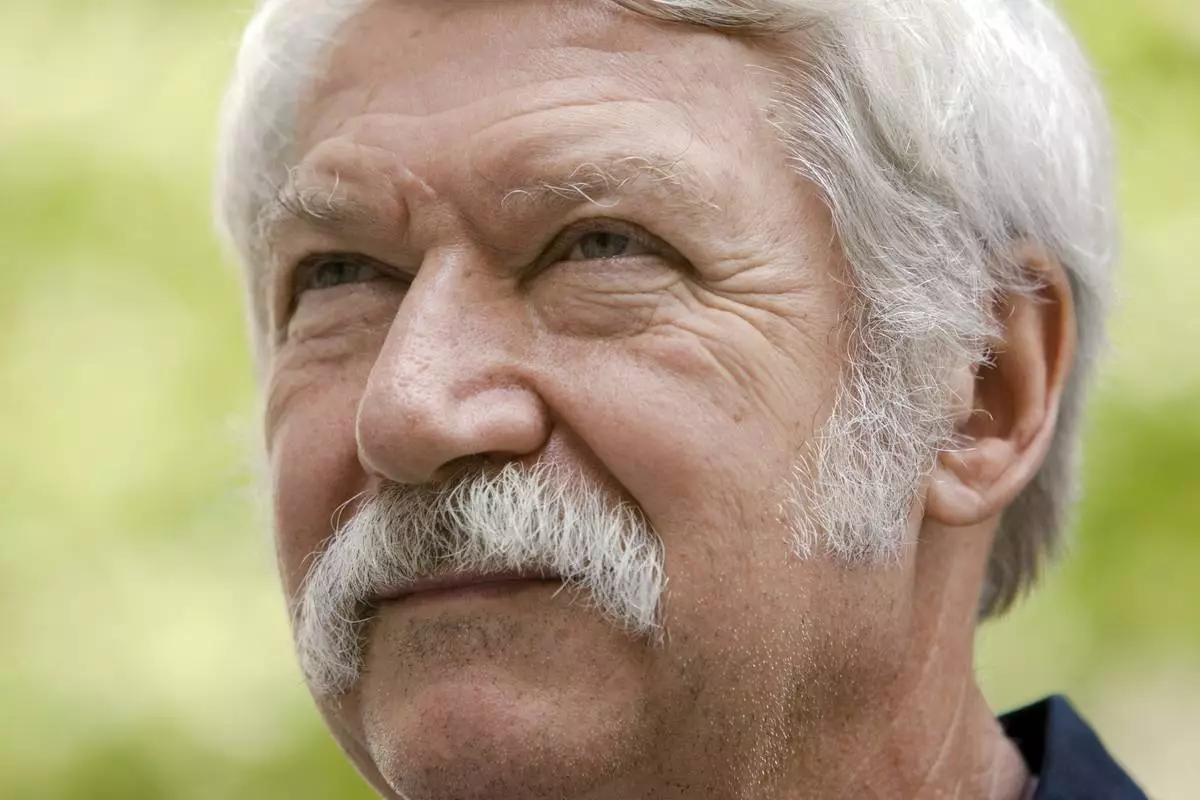

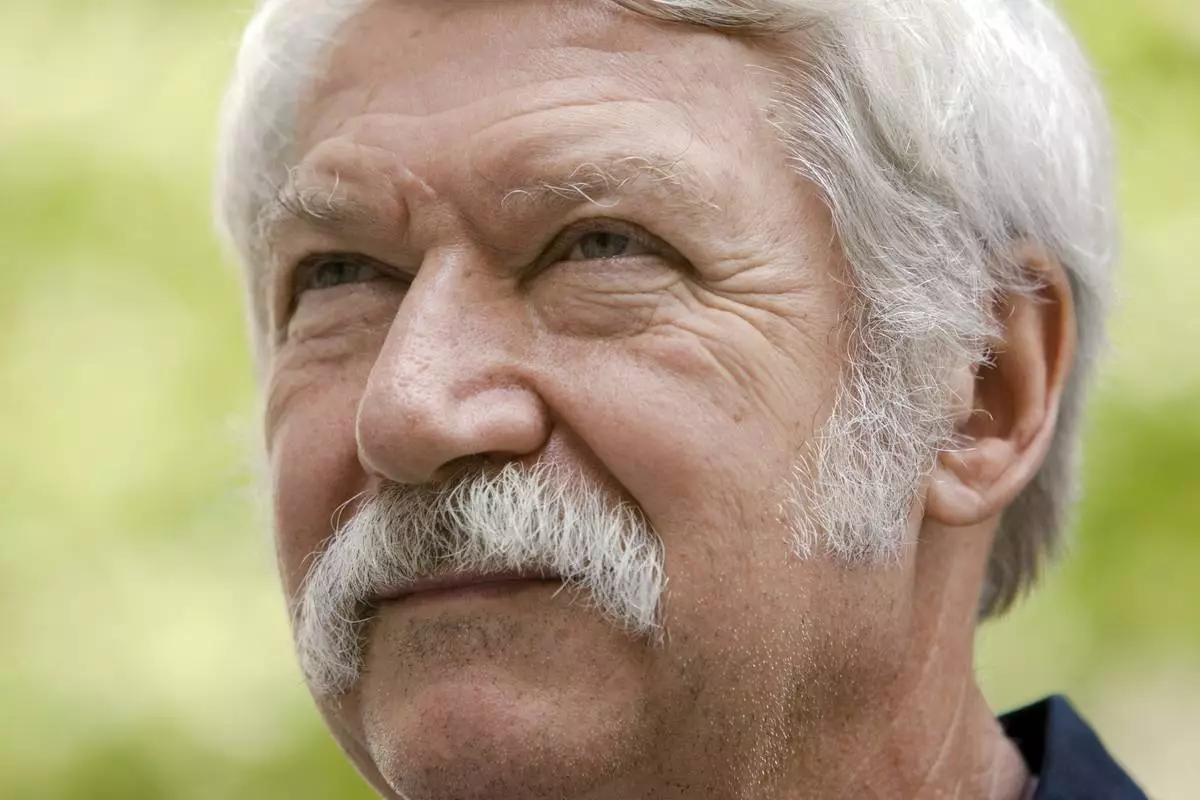

Bela Karolyi, the charismatic if polarizing gymnastics coach who turned young women into champions and the United States into an international power in the sport, has died. He was 82.

USA Gymnastics said Karolyi died Friday. No cause of death was given.

Karolyi and wife Martha trained multiple Olympic gold medalists and world champions in the U.S. and Romania, including Nadia Comaneci and Mary Lou Retton.

“A big impact and influence on my life,” Comaneci, who was just 14 when Karolyi coached her to gold for Romania at the 1976 Montreal Olympics, posted on Instagram.

Yet Karolyi's strident methods sometimes came under fire, most pointedly during the height of the Larry Nassar scandal.

When the disgraced former USA Gymnastics team doctor was effectively given a life sentence after pleading guilty to sexually assaulting gymnasts and other athletes with his hands under the guise of medical treatment, over a dozen former gymnasts came forward saying the Karolyis were part of a system that created an oppressive culture that allowed Nassar’s behavior to run unchecked for years.

While the Karolyis denied responsibility — telling CNN in 2018 they were unaware of Nassar's behavior — the revelations led to them receding from the spotlight. USA Gymnastics eventually exited an agreement to continue to train at the Karolyi Ranch north of Houston, though only after American star Simone Biles took the organization to task for having them train at a site where many experienced sexual abuse.

The Karolyis faded from prominence in the aftermath after spending 30-plus years as a guiding force in American gymnastics, often basking in success while brushing with controversy in equal measure.

The Karolyis defected from Romania to the United States in 1981. Three years later Bela helped guide Retton — all of 16 — to the Olympic all-around title at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. At the 1996 Games in Atlanta, he memorably helped an injured Kerri Strug off the floor after Strug's vault secured the team gold for the Americans.

Karolyi briefly became the national team coordinator for USA Gymnastics women's elite program in 1999 and incorporated a semi-centralized system that eventually turned the Americans into the sport's gold standard. It did not come without a cost. He was removed from the position after the 2000 Olympics when it became apparent his leadership style simply would not work, though he remained around the sport after Martha took over for her husband in 2001.

While the Karolyis approach helped the U.S. become a superpower — an American woman has won each of the last six Olympic titles and the U.S. women earned the team gold at the 2012 and 2016 Games under Martha Karolyi's leadership — their methods came under fire.

Dominique Moceanu, part of the “Magnificent 7” team that won gold in Atlanta, talked extensively about her corrosive relationship with the Karolyis following her retirement. In her 2012 memoir, Moceanu wrote Bela Karolyi verbally abused her in front of her teammates on multiple occasions.

“His harsh words and critical demeanor often weighed heavily on me,” Moceanu posted on X Saturday. “While our relationship was fraught with difficulty, some of these moments of hardship helped me forge and define my own path.”

Some of Karolyi's most famous students were always among his staunchest defenders. When Strug got married, she and Karolyi took a photo recreating their famous scene from the 1996 Olympics, when he carried her onto the medals podium after she vaulted on a badly sprained ankle.

Being a gymnastics pied-piper was never Karolyi’s intent. Born in Clug, Hungary (now Romania) on Sept. 13, 1942, he wanted to be a teacher, getting into coaching in college simply so he could spend more time with Martha.

After graduating, the couple moved to a small coal-mining town in Transylvania. Looking for a way to keep their students warm and entertained during the long, harsh winters, Karolyi dragged out some old mats and he and his wife taught the children gymnastics.

The students showed off their skills to their parents, and the exhibitions soon caught the eye of the Romanian government, which hired the Karolyis to coach the women’s national team at a time when the sport was done almost exclusively by adult women, not young girls.

Karolyi changed all that, though, bringing a team to the Montreal Olympics with only one gymnast older than 14.

It was in Montreal, of course, where the world got its first real glimpse of Karolyi. When a solemn, dark-haired sprite named Nadia Comaneci enchanted the world with the first perfect 10 in Olympic history, a feat she would duplicate six times, Karolyi was there to wrap her in one of his trademark bear hugs.

Romania, which had won only three bronzes in Olympic gymnastics before 1976, left Montreal with seven medals, including Comaneci’s golds in the all-around, balance beam and uneven bars, and the team silver. Comaneci became an international sensation, the first person to appear on the covers of Sports Illustrated, Time and Newsweek in the same week.

Four years later, however, Karolyi was in disgrace.

He was incensed by the judging at the Moscow Olympics, which he thought cost Comaneci a second all-around gold, and the Romanian government was horrified that he had embarrassed the Soviet hosts.

“Suddenly, from a position where we’ve been praised and considered the foremost athletes in the country, I was stigmatized,” he once said. “I thought they could put me away for political misconduct.”

When he and Martha took the Romanian team to New York for an exhibition in March 1981, they were tipped off that they were going to be punished upon their return. Despite not speaking any English and with their then-6-year-old daughter, Andrea, still in Romania, they decided to defect.

“We knew what kind of risks we were taking, because nobody was guaranteeing us anything,” Martha Karolyi once said. “We started out with a suitcase and a little motel room. From there, it’s gradually improved.”

The couple made their way to California, where they learned English by watching television and Bela did odd jobs. A chance encounter with Olympic gold medalist Bart Conner — who would later marry Comaneci — at the Los Angeles airport a few months later led to the Karolyis’ first coaching job in the United States.

Within a year, their daughter had arrived in the U.S. and the Karolyis had their own gym in Houston. It soon became the center of American gymnastics, turning out eight national champions in 13 years.

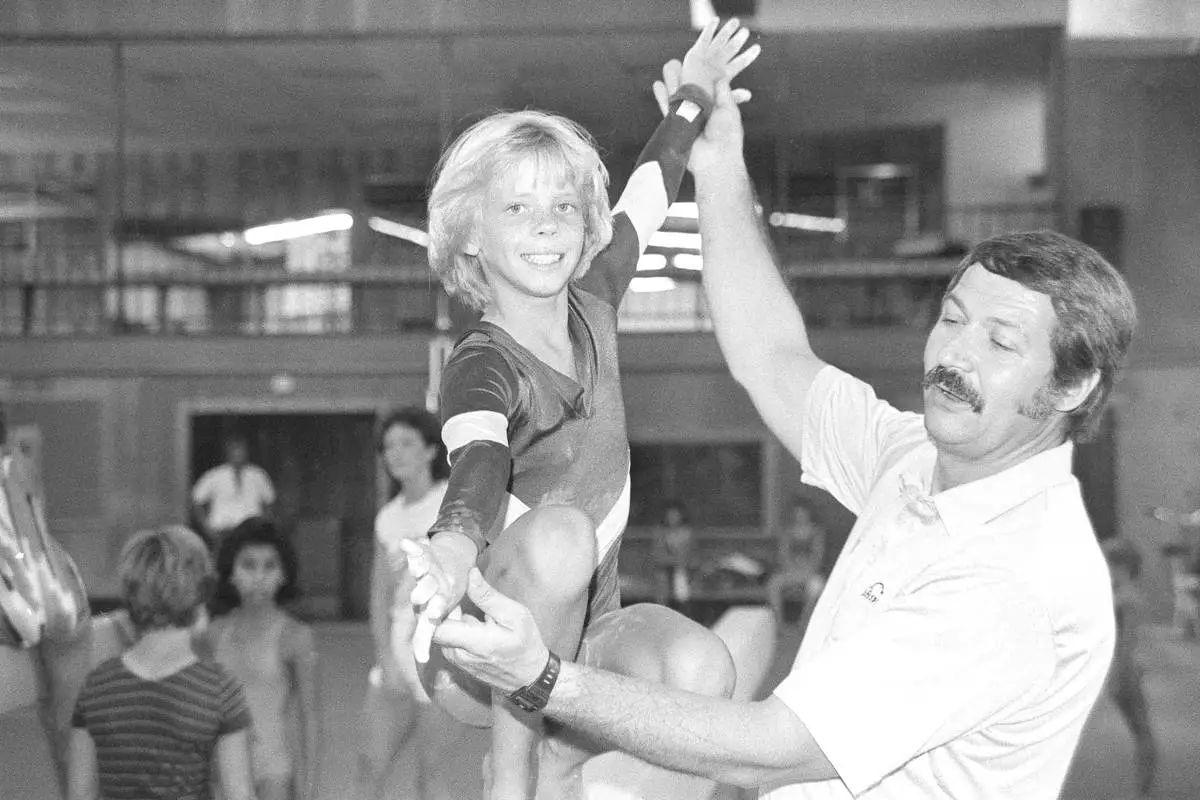

Three years after the Karolyis left Romania, Retton became the first American to win the Olympic all-around title, scoring a perfect 10 on vault to claim gold at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. Retton also posted the highest score in the team competition as the Americans won the silver, their first team medal since 1948.

Four years later, Phoebe Mills, another Karolyi gymnast, won a bronze on balance beam. It was the first individual medal for an American woman at a non-boycotted Games. And in 1991, Kim Zmeskal — “the little Kimbo,” as Bela Karolyi called her — became the first American to win the world all-around title.

“My biggest contribution was giving the kids the faith that they can be the best among the best,” Karolyi once said. “I knew that if the Americans could understand they were not inferior ... then they can be groomed like international, highly visible athletes.”

But as Karolyi’s resume grew, so did the criticism.

Other coaches were irritated by his brash personality and ability to always find his way into the spotlight. When Retton won gold, Karolyi leaped a barrier — he had an equipment manager’s credential, not a coach’s — so he could scoop Retton up in a hug — right in front of the TV cameras, of course.

He could be a harsh taskmaster, calling his gymnasts names, taunting them for their weight and pushing them to their limits.

Even those warm embraces weren’t always quite what they seemed.

“A lot of those big bear hugs came with the whisper of `Not so good,’ in our ears,” Retton wrote.

Yet Retton and Comaneci remained close with Karolyi, making appearances with him at gymnastics events or sitting with him at competitions. Zmeskal had her wedding at the Karolyi ranch.

Karolyi briefly retired after the 1992 Games in Barcelona, where he led the Americans to their first team medal, a bronze, at a non-boycotted Olympics in 44 years. But he kept his gym and summer camps, and by 1994 was again coaching elite-level gymnasts after Zmeskal asked him to help in her attempt to make the Atlanta Games.

Zmeskal didn’t make the Atlanta squad. But two of Karolyi’s other gymnasts, Strug and Moceanu, did, and it was Strug who provided one of the signature moments of the Olympics.

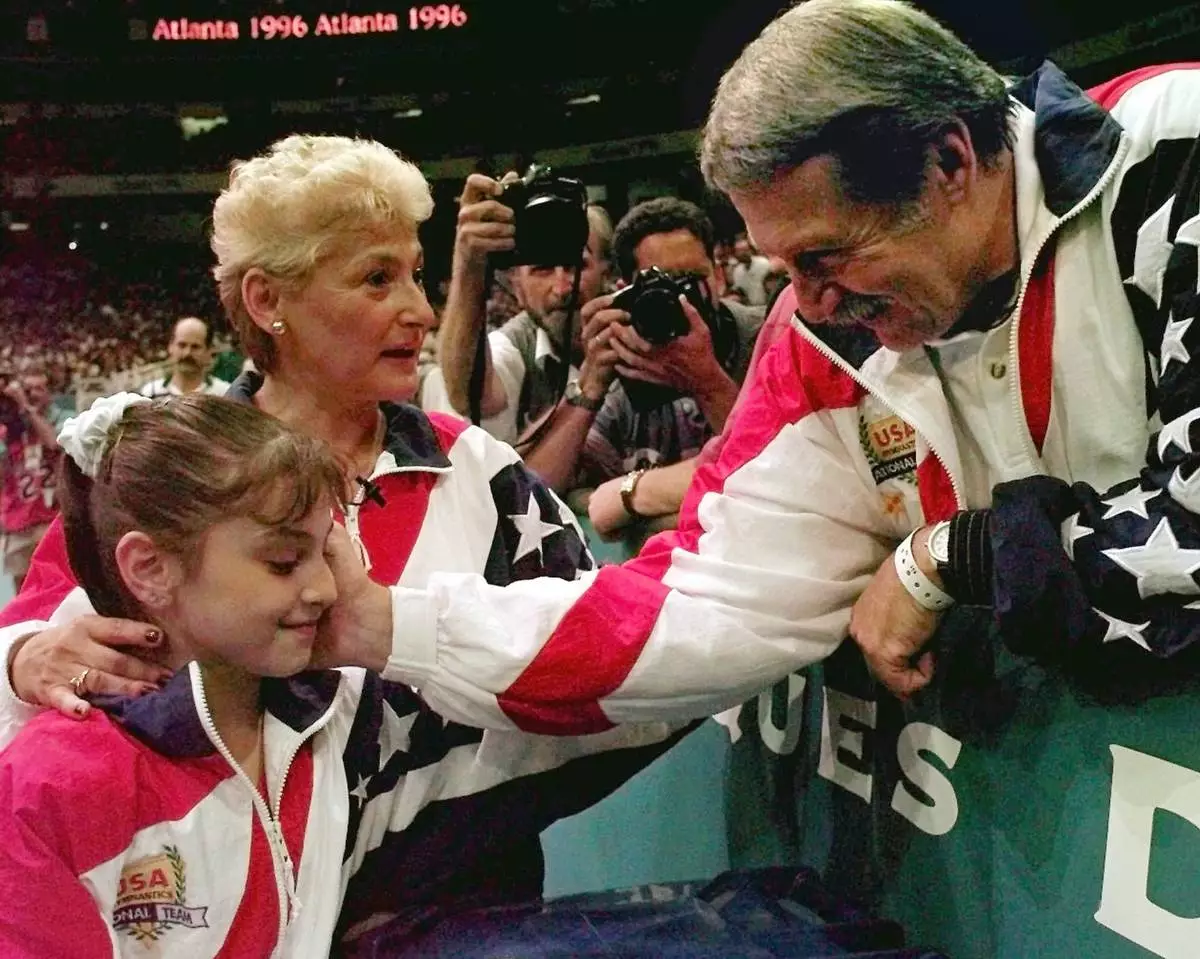

The Americans went into their final event in team finals, vault, trying to hold off Russia for their first-ever title at an Olympics or world championships. Despite injuring her left ankle when she fell on her first vault attempt, Strug went ahead with her second attempt, believing — wrongly — the Americans needed her score to clinch the gold.

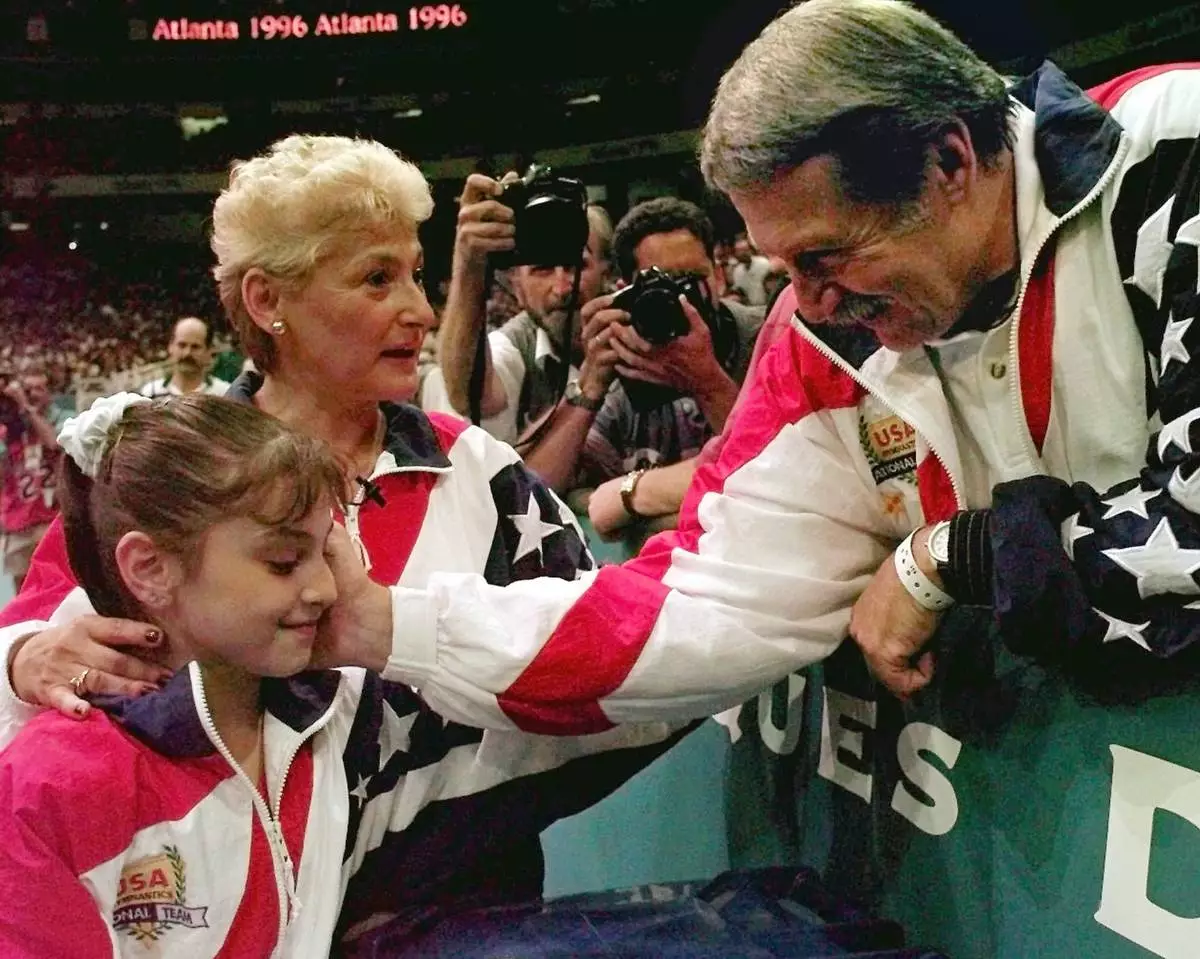

With Karolyi shouting, “You can do it!” Strug sprinted down the runway, soared high above the vault and landed on both feet — ensuring it was a clean vault — before pulling her left leg up. After saluting the judges, she fell to her knees and had to be carried off the podium. Tests would later show she had two torn ligaments in her ankle.

As the rest of the Americans gathered on the podium to receive their gold medals, Karolyi carried Strug back into the arena, cradling her in his arms.

But even that drew criticism. Many said Karolyi never should have encouraged Strug to vault on her injured ankle in the first place, and then should have stayed out of the spotlight rather than carrying her to the podium.

“Bela is a very tough coach and he gets criticism for that,” Strug said at the time. “But that’s what it takes to become a champion. I don’t think it’s really right that everyone tries to find the faults of Bela. Anything in life, to be successful, you’ve got to work really hard.”

The Karolyis retired again after the Atlanta Olympics. But after the U.S. women finished last in the medal round at the 1997 world championships, USA Gymnastics asked Bela Karolyi to come back.

He agreed — but only if he could implement a semi-centralized training system. Rather than a patchwork system of individual coaches who had their own philosophies, Karolyi would oversee the entire U.S. program. Gymnasts could still train with their own coaches, but there would be regular national team camps to ensure they were meeting established training and performance standards.

Though the idea was sound, Karolyi was not the right person to be in charge. Coaches who had been his equal chafed at his heavy-handedness, and were annoyed by his grandstanding. Gymnasts resented his bluster and demands.

By the time the Americans left the Sydney Olympics, about the only thing everyone agreed on was that Karolyi needed to step away.

He stepped aside and was replaced by his wife. Martha Karolyi’s standards were just as high — if not higher — than her husband’s, but on the surface, she was more willing to listen to other opinions.

“She’s more diplomatic. Absolutely,” Bela Karolyi said before the 2012 Olympics. “I’m wild. The opposite.”

AP sports: https://apnews.com/sports

FILE - Gymnastics coach Bela Karolyi is seen in Philadelphia, June 16, 2008. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, File)

FILE - USA's Kerri Strug is carried by her coach, Bela Karolyi, as she waves to the crowd on her way to receiving her gold medal for the women's team gymnastics competition, at the Centennial Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta, July 23, 1996. Strug had two torn ligaments and a sprained ankle from the vault competition. (AP Photo/Susan Ragan, File)

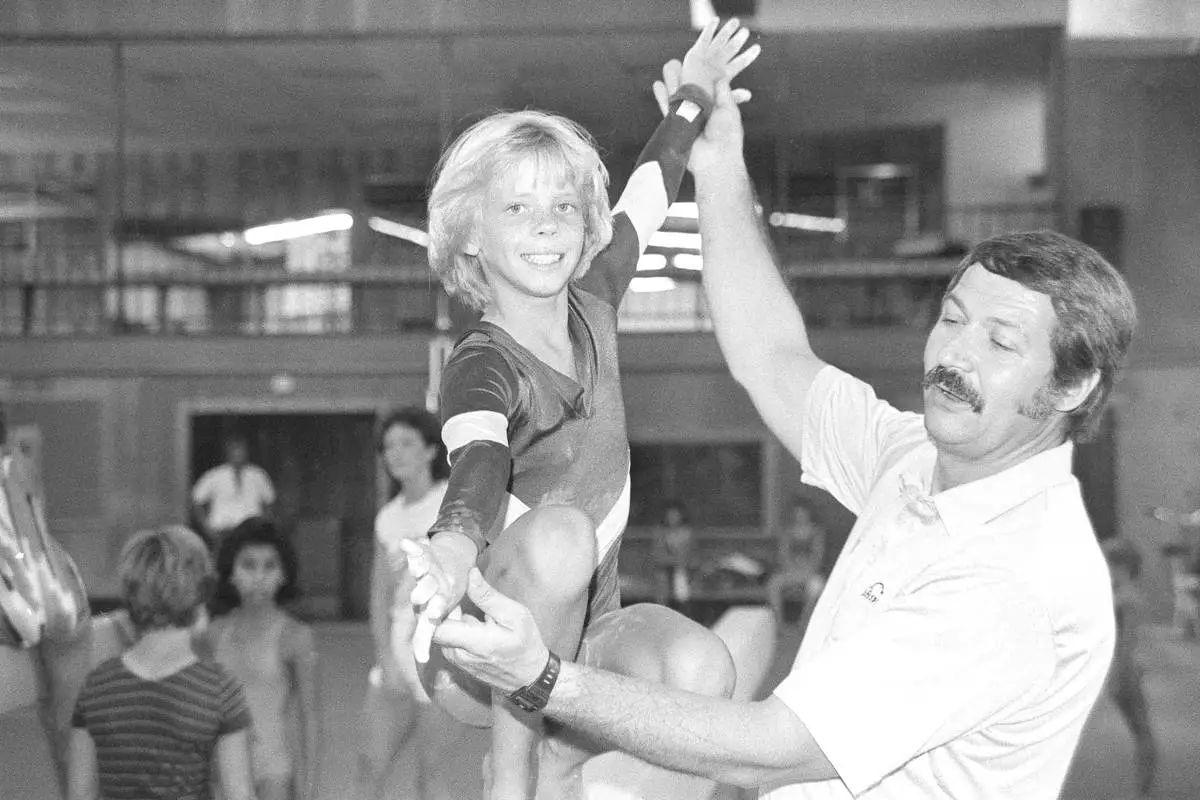

FILE - Mary Lou Retton of the USA is hugged by her coach, Bela Karolyi, following her perfect performance in the floor exercise in Olympic individual all-around finals, Aug. 3, 1984, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Sadayuki Mikami, File)

FILE - Bela Karolyi, left, and his wife, Martha Karolyi, talk on the arena floor before the start of the preliminary round of the women's Olympic gymnastics trials in San Jose, Calif., June 29, 2012. (AP Photo/Gregory Bull, File)

FILE - Olympic gymnastics coach Bela Karolyi, right, instructs Sara Tank on the balance beam at his Olympic training facility in north Houston, Aug. 12, 1985. (AP Photo/Richard J. Carson, File)

FILE - Bela Karolyi reacts with joy as his gymnastics student Kerri Strug finishes a nice routine on the balance beam during the optional portion of the U.S. Olympic Trials in gymnastics, June 30, 1996, in Boston. (AP Photo/Elise Amendola, File)

FILE - Bela Karolyi speaks during the opening of his training center for the U.S. gymnastics women's national team in Huntsville, Texas, May 19, 2003. (Travis Bartoshek/The Huntsville Item via AP, File)

FILE - Bela Karolyi, right, congratulates Dominique Moceanu, left, after the United States captured the gold medal in the women's team gymnastics competition at the Centennial Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta, July 23, 1996. (AP Photo/Amy Sancetta, File)