Tensions along the China-India border high in the Himalayas have flared again in recent weeks.

Indian officials say the latest row began in early May, when Chinese soldiers entered the Indian-controlled territory of Ladakh at three different points, erecting tents and guard posts. They said the Chinese soldiers ignored repeated verbal warnings to depart, triggering shouting matches, stone-throwing and fistfights. China has sought to downplay the confrontation while providing little information.

A look at the history and current relations between the two countries and how events may develop:

In this July 22, 2011, file photo, children play cricket by Pangong Lake, near the India-China border in Ladakh, India. Indian officials say Indian and Chinese soldiers are in a bitter standoff in the remote and picturesque Ladakh region, with the two countries amassing soldiers and machinery near the tense frontier. The officials said the standoff began in early May when large contingents of Chinese soldiers entered deep inside Indian-controlled territory at three places in Ladakh, erecting tents and posts. (AP PhotoChanni Anand, File)

BRAWLING TROOPS

Over recent weeks, thousands of soldiers from the two countries have been facing off just a few hundred meters (yards) from each other in Ladakh’s Galwan Valley. China has objected to India building a road through the valley connecting the region to an airstrip, possibly sparking its move to assert control over territory along the border that is not clearly defined in places.

While a brawl between troops has been captured on video, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said Wednesday that the border situation was “generally stable and controllable.”

FILE-In this June 17, 2016, file photo, an Indian tourist rides on a horse back at the Pangong Lake high up in Ladakh region of India. Tensions along the China-India border high in the Himalayas have flared again in recent weeks. Indian officials say the latest row began in early May when Chinese soldiers entered the Indian-controlled territory of Ladakh at three different points, erecting tents and guard posts. (AP PhotoManish Swarup, File)

The sides were communicating through both their front-line military units and their respective embassies to “properly resolve relevant issues through dialogue and consultation,” Zhao said at a daily ministry news briefing in Beijing.

India and China engaged in a similar standoff for 73 days at Doklam, at the other end of their disputed border, in 2017, when Indian troops were mobilized to counter what was seen as moves by the Chinese side to expand its presence along the border with Bhutan. The situation was later defused through diplomatic channels.

WAR AND PEACE BETWEEN TWO ASIAN GIANTS

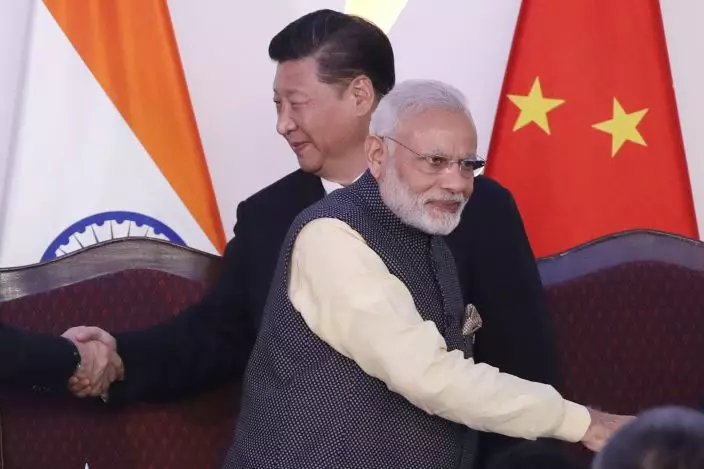

In this Oct. 16, 2016, file photo, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, front and Chinese President Xi Jinping shake hands with leaders at the BRICS summit in Goa, India. Tensions along the China-India border high in the Himalayas have flared again in recent weeks. Indian officials say the latest row began in early May when Chinese soldiers entered the Indian-controlled territory of Ladakh at three different points, erecting tents and guard posts. (AP PhotoManish Swarup, File)

The sides established diplomatic relations in 1950, but a 1962 border war between them set back ties for decades.

In all, China claims some 90,000 square kilometers (35,000 square miles) of territory in India’s northeast, including the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh with its traditionally Buddhist population. India says China occupies 38,000 square kilometers (15,000 square miles) of its territory in the Aksai Chin Plateau in the western Himalayas, including part of the Ladakh region.

Relations are also strained by India’s hosting of the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, who fled his homeland in 1959 during an aborted uprising against Chinese rule. The Dalai Lama established a self-declared government-in-exile in the northern Indian town of Dharmsala, where thousands of Tibetans have settled.

FILE- In this Oct. 10, 2019 file photo, an Indian schoolgirl wears a face mask of Chinese President Xi Jinping to welcome him on the eve of his visit in Chennai, India. Tensions along the China-India border high in the Himalayas have flared again in recent weeks. Indian officials say the latest row began in early May when Chinese soldiers entered the Indian-controlled territory of Ladakh at three different points, erecting tents and guard posts. (AP PhotoR. Parthibhan, File)

EFFORTS FOR A RESOLUTION

In 1993, the two countries signed an agreement on the “Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility” along what is known as the Line of Actual Control along their border.

But they are nowhere near to settling their dispute despite more than 20 rounds of talks along with multiple meetings between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Beijing’s support for Pakistan on the issue of the disputed territory of Kashmir is also a major cause of concern for India. China has built a road through Pakistani-controlled Kashmir and is blocking India’s entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group by insisting on Pakistan’s simultaneous entry. India’s refusal to participate in Xi’s signature foreign policy initiative, the multibillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, hasn’t gone down well with China, while Beijing has paid only lip service to New Delhi’s aspirations to join the U.N. Security Council as a permanent member.

ECONOMIC RIVALRY AMID GROWING TRADE

Despite the sporadic border clashes, economic ties between the two have expanded in the past decade, with China exercising a large trade surplus.

More than 100 Chinese companies, many of them state-owned, have established offices or operations in India, according to India’s External Affairs Ministry. Chinese firms including Xiaomi, Huawei, Vivo and Oppo occupy nearly 60% of India’s mobile phone market, while India’s major exports to China lean toward cotton, copper and gemstones.

Trade volume rose to more than US$95 billion in 2018, and passed $53 billion in the first half of 2019, with almost $43 billion of that being Chinese exports to India. The imbalance has contributed to a push by India to capitalize on China’s rising costs and deteriorating ties with the United States and European nations to become a replacement home for large multinationals.