In a move that ends a tradition dating more than 150 years, Major League Baseball approved the use of an electronic device for catchers to signal pitches in an effort to eliminate sign stealing and speed games.

Since the beginning of baseball in the 19th century, catchers had used their fingers to signal the type of pitch and its intended location.

As video at balllparks increased in the 21st century, so did sign stealing — and worries about how teams were trying to swipe signals. The Houston Astros were penalized for using a camera and banging a trash can to alert their batters to pitch types during their run to the 2017 World Series title.

Seattle Mariners catcher Tom Murphy wears a wrist-worn device used to call pitches as he catches a ball during the sixth inning of a spring training baseball game against the Kansas City Royals, Tuesday, March 29, 2022, in Peoria, Ariz. The MLB is experimenting with the PitchCom system where the catcher enters information on a wrist band with nine buttons which is transmitted to the pitcher to call a pitch. (AP PhotoCharlie Riedel)

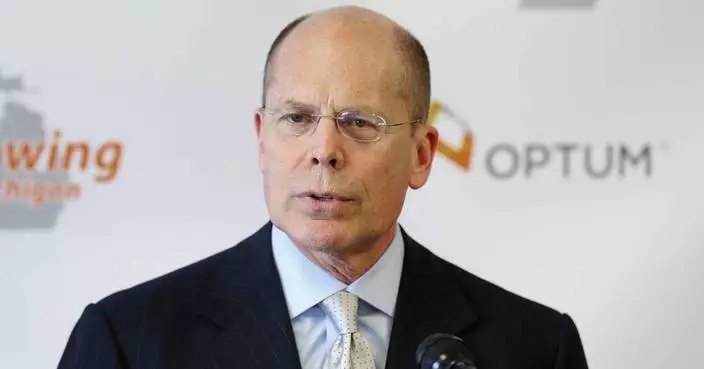

“It basically eliminates all need to create a sign system, for a catcher giving signs,” MLB chief operations and strategy officer Chris Marinak said Tuesday. “You literally just press a button and it delivers the pitch call to the pitcher. And what we've seen so far, it really improves pace of game."

Some teams tried the system in spring training, with manager Tony La Russa of the Chicago White Sox and Aaron Boone of the New York Yankees among those saying they liked what they saw.

MLB is providing each team with three transmitters, 10 receivers and a charging case for the PitchCom Pitcher Catcher Communication Device.

Chris Zagorski, vice president of replay operations and technology at Major League Baseball, watches Spring Training games on screens inside the replay room at MLB headquarters, Tuesday, April 5, 2022 in New York. In an effort to eliminate sign stealing, Major League Baseball says catchers may use a new electronic signal system to call pitches this season. (AP PhotoRon Blum)

“A maximum of five receivers and one transmitter may be in any use at any given time," MLB wrote in a five-page memorandum Tuesday to general managers, assistant GMs, managers and equipment managers, a copy of which was obtained by The Associated Press.

A catcher has nine choices on his wristband device: “four seam high inside, curve hi middle, slider hi outside, change mid inside, sinker middle, cutter mid out, splitter low inside, knuckle lo middle, two seam low outside.”

A thin band tucked inside a cap allows the audio to be heard at an adjustable level, envisioned to be used by pitchers, second baseman, shortstops and center fielders.

Kansas City Royals catcher Cam Gallagher wears a wrist-worn device used to call pitches as he prepares to bat during the sixth inning of a spring training baseball game against the Seattle Mariners, Tuesday, March 29, 2022, in Peoria, Ariz. The MLB is experimenting with the PitchCom system where the catcher enters information on a wrist band with nine buttons which is transmitted to the pitcher to call a pitch. (AP PhotoCharlie Riedel)

“When changing pitchers, the manager shall provide a receiver to the replacement pitcher,” the memo said.

Receivers and transmitters can be used only on the field and may not be operated during games in clubhouses, dugouts or bullpens.

“Signals communicated via PitchCom may only be given by the catcher in the game. Signals may not be sent from the dugout, bullpen, a different player in the field, or anywhere else,” the memo said. “Clubs are responsible for their PitchCom devices. Any club that loses a transmitter or receiver will be charged a replacement fee of $5,000 per unit.”

Marinak said about half of the 30 MLB clubs had expressed interest.

“I'm not sure that every team will use it," Marinak said during MLB's third annual innovation and fan engagement showcase. “I think this is a kind of a personal preference kind of thing.”

Players may not longer watch in-game video replays on clubhouse televisions but may review video only on iPads controlled by the MLB office. The video will be updated only at the end of each half-inning and players can go back and replay, but may not see content during a half-inning in progress.

“Players don't have access to any technology that's above and beyond what we're offering in terms of in-game video," Marinak said. "We also monitor all the transmission of traffic so that we understand what content is being delivered to the iPad.”

The new system of umpires having microphones to explain video reviews to fans began with an exhibition game at Dodger Stadium on Monday night. MLB also is now taking in video from 104 of 120 minor league ballparks

The automated ball/strike system of computer plate umpires will be used at 10 Triple-A West parks, Charlotte in Triple-A East and Low-A Southeast. MLB intends to illustrate the calls on stadium scoreboards.

Pitch clocks will be used at all minor league stadiums, likely a prelude to their installation at big league ballparks for 2023.

MLB showed off its new 1,400-square foot replay operations center in midtown Manhattan, which opened just as COVID-19 struck in 2020 and replaced a 900-square foot facility in SoHo that had been used since 2014.

There are 90 46-inch professional monitors and 60 24-inch touchscreen monitors in the 31 x 29-foot room, with three desks with six screens behind them for supervisors and administrators, then two more rows with technicians.

MLB takes in 18 cameras from each ballpark showing 60 frames per second plus up to four high-speed cameras as fast as 360-480 frames per second, according to Chris Zagorski, vice president of replay operations and technology.

There is a backup replay center in San Francisco, in case of a power outage in New York. For special event games such as in Dyersville, Iowa, Williamsport, Pennsylvania, and London, a replay room is set up on site.

Marinak said that fans using the MLB Ballpark app to enter stadiums with electronic tickets rose from 3% in 2017 to 19% in 2019 to 56% in 2021.

More AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/MLB and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

HWANGE, Zimbabwe (AP) — When GPS-triggered alerts show an elephant herd heading toward villages near Zimbabwe's Hwange National Park, Capon Sibanda springs into action. He posts warnings in WhatsApp groups before speeding off on his bicycle to inform nearby residents without phones or network access.

The new system of tracking elephants wearing GPS collars was launched last year by the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority and the International Fund for Animal Welfare. It aims to prevent dangerous encounters between people and elephants, which are more frequent as climate change worsens competition for food and water.

“When we started it was more of a challenge, but it’s becoming phenomenal,” said Sibanda, 29, one of the local volunteers trained to be community guardians.

For generations, villagers banged pots, shouted or burned dung to drive away elephants. But worsening droughts and shrinking resources have pushed the animals to raid villages more often, destroying crops and infrastructure and sometimes injuring or killing people.

Zimbabwe's elephant population is estimated at around 100,000, nearly double the land’s capacity. The country hasn’t culled elephants in close to four decades. That's because of pressure from wildlife conservation activists, and because the process is expensive, according to parks spokesman Tinashe Farawo.

Conflicts between humans and wildlife such as elephants, lions and hyenas killed 18 people across the southern African country between January and April this year, forcing park authorities to kill 158 “trouble” animals during that period.

“Droughts are getting worse. The elephants devour the little that we harvest,” said Senzeni Sibanda, a local councilor and farmer, tending her tomato crop with cow dung manure in a community garden that also supports a school feeding program.

Technology now supports the traditional tactics. Through the EarthRanger platform introduced by IFAW, authorities track collared elephants in real time. Maps show their proximity to the buffer zone — delineated on digital maps, not by fences — that separate the park and hunting concessions from community land.

At a park restaurant one morning IFAW field operations manager Arnold Tshipa monitored moving icons on his laptop as he waited for breakfast. When an icon crossed a red line, signaling a breach, an alert pinged.

“We’re going to be able to see the interactions between wildlife and people,” Tshipa said. “This allows us to give more resources to particular areas."

The system also logs incidents like crop damage or attacks on people and livestock by predators such as lions or hyenas and retaliatory attacks on wildlife by humans. It also tracks the location of community guardians like Capon Sibanda.

“Every time I wake up, I take my bike, I take my gadget and hit the road,” Sibanda said. He collects and stores data on his phone, usually with photos. “Within a blink,” alerts go to rangers and villagers, he said.

His commitment has earned admiration from locals, who sometimes gift him crops or meat. He also receives a monthly food allotment worth about $80 along with internet data.

Parks agency director Edson Gandiwa said the platform ensures that “conservation decisions are informed by robust scientific data.”

Villagers like Senzeni Sibanda say the system is making a difference: “We still bang pans, but now we get warnings in time and rangers react more quickly.”

Still, frustration lingers. Sibanda has lost crops and water infrastructure to elephant raids and wants stronger action. “Why aren’t you culling them so that we benefit?” she asked. “We have too many elephants anyway.”

Her community, home to several hundred people, receives only a small share of annual trophy hunting revenues, roughly the value of one elephant or between $10,000 and $80,000, which goes toward water repairs or fencing. She wants a rise in Zimbabwe's hunting quota, which stands at 500 elephants per year, and her community's share increased.

The elephant debate has made headlines. In September last year, activists protested after Zimbabwe and Namibia proposed slaughtering elephants to feed drought-stricken communities. Botswana’s then-president offered to gift 20,000 elephants to Germany, and the country’s wildlife minister mock-suggested sending 10,000 to Hyde Park in the heart of London so Britons could “have a taste of living alongside elephants.”

Zimbabwe's collaring project may offer a way forward. Sixteen elephants, mostly matriarchs, have been fitted with GPS collars, allowing rangers to track entire herds by following their leaders. But Hwange holds about 45,000 elephants, and parks officials say it has capacity for 15,000. Project officials acknowledge a huge gap remains.

In a recent collaring mission, a team of ecologists, vets, trackers and rangers identified a herd. A marksman darted the matriarch from a distance. After some tracking using a drone and a truck, team members fitted the collar, whose battery lasts between two and four years. Some collected blood samples. Rangers with rifles kept watch.

Once the collar was secured, an antidote was administered, and the matriarch staggered off into the wild, flapping its ears.

“Every second counts,” said Kudzai Mapurisa, a parks agency veterinarian.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority officers record measurements of an elephant in the Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

An official shows how the EarthRanger platform operates at Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

A GPS-enabled satellite collar on an elephant in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority and the International Fund for Animal Welfare officers collar an elephant in the Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Capon Sibanda, a local volunteer trained to be a community guardian for encounters between people and elephants, rides on a bicycle in Hwange, Zimbabwe, Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority and the International Fund for Animal Welfare officers stand around a collared elephant in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

An elephant walks in the Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Monday, April 28 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority and the International Fund for Animal Welfare officers monitor an elephant's movement using a drone in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority officer carries a collar to be used to track an in elephant in the Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Kudzai Mapurisa, a Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority veterinarian, prepares to dart an elephant in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

A Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority ranger carries a dart gun for elephants in the Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, Tuesday, April 29, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)

Capon Sibanda, left, a community guardian for encounters between people and elephants, talks with Senzeni Sibanda, a local councilor and farmer, in Hwange, Zimbabwe, Wednesday, April 30, 2025. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli)