NEW YORK (AP) — Whitey Herzog, the gruff and ingenious Hall of Fame manager who guided the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and a World Series title in the 1980s and perfected an intricate, nail-biting strategy known as "Whiteyball," has died. He was 92.

Cardinals spokesman Brian Bartow said Tuesday the team had been informed of Herzog's death by his family. Herzog, who had been at Busch Stadium on April 4 for the Cardinals' home opener, died on Monday, according to Bartow.

“Whitey Herzog devoted his lifetime to the game he loved, excelling as a leader on and off the field,” Jane Forbes Clark, chair of the Hall of Fame's board of directors, said in a statement. “Whitey always brought the best out of every player he managed with a forthright style that won him respect throughout the game.”

A crew-cut, pot-bellied tobacco chewer who had no patience for the "buddy-buddy" school of management, Herzog joined the Cardinals in 1980 and helped end the team's decade-plus pennant drought by adapting it to the artificial surface and distant fences of Busch Memorial Stadium. A typical Cardinals victory under Herzog was a low-scoring, 1-run game, sealed in the final innings by a “bullpen by committee,” relievers who might be replaced after a single pitch, or temporarily shifted to the outfield, then brought back to the mound.

The Cardinals had power hitters in George Hendrick and Jack Clark, but they mostly relied on the speed and resourcefulness of switch-hitters Vince Coleman and Willie McGee, the acrobatic fielding of shortstop and future Hall of Famer Ozzie Smith and the effective pitching of starters such as John Tudor and Danny Cox and relievers Todd Worrell, Ken Dayley and Jeff Lahti. For the '82 champions, Herzog didn't bother rotating relievers, but simply brought in future Hall of Famer Bruce Sutter to finish the job.

"They (the media) seemed to think there was something wrong with the way we played baseball, with speed and defense and line-drive hitters," Herzog wrote in his memoir "White Rat: A Life in Baseball," published in 1987. "They called it 'Whiteyball' and said it couldn't last."

Under Herzog, the Cards won pennants in 1982, 1985 and 1987, and the World Series in 1982, when they edged the Milwaukee Brewers in seven games. Herzog managed the Kansas City Royals to division titles in 1976-78, but they lost each time in the league championship to the New York Yankees.

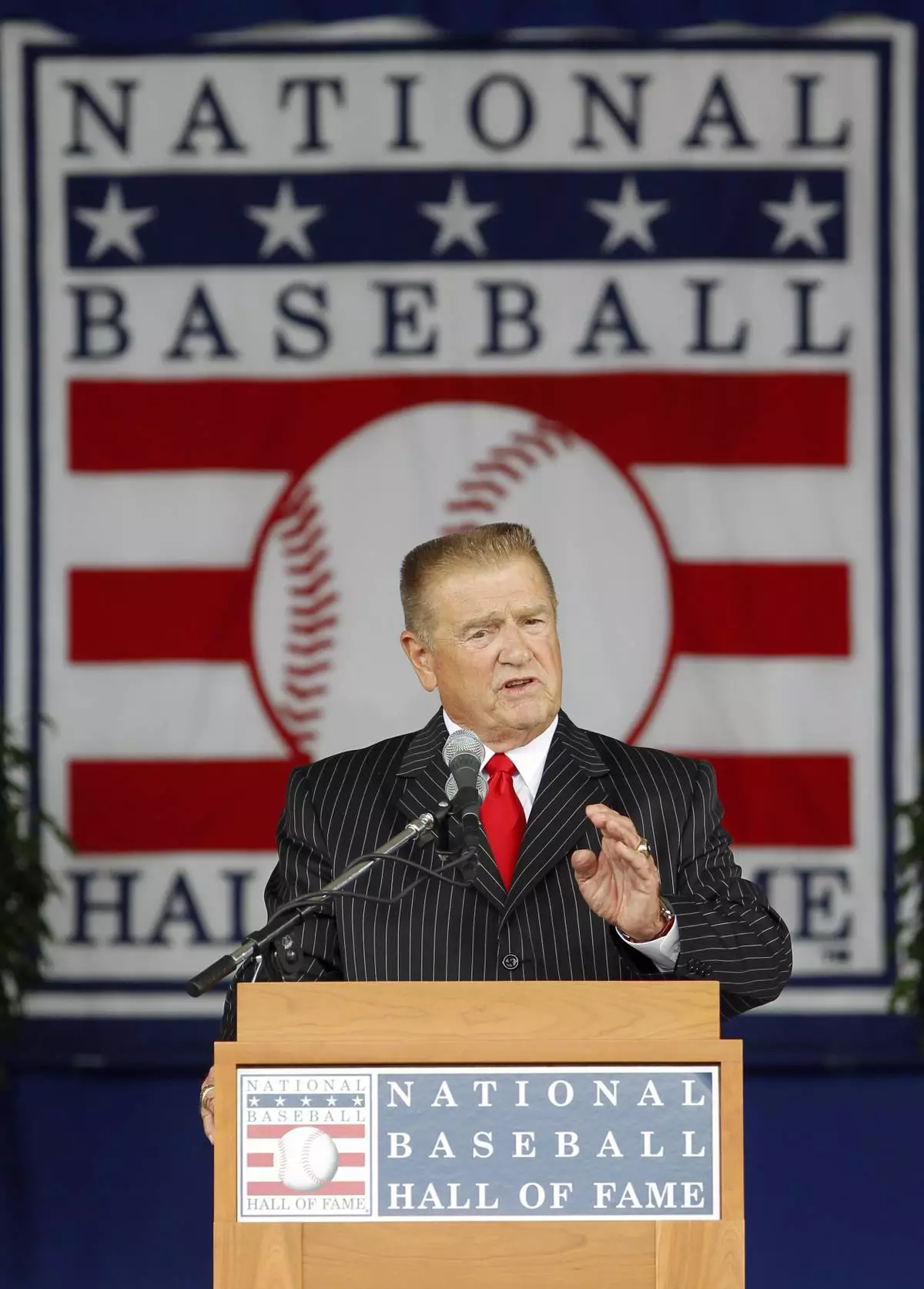

Overall, Herzog was a manager for 18 seasons, compiling a record of 1,281 wins and 1,125 losses. He was named Manager of the Year in 1985 and voted into the Hall by the Veterans Committee in 2010, his plaque noting his "stern, yet good-natured style," and his emphasis on speed, pitching and defense. Just before he formally entered the Hall, the Cardinals retired his uniform number, 24.

When asked about the secrets of managing, he would reply a sense of humor and a good bullpen.

Herzog is survived by his wife of 71 years, Mary Lou Herzog; their three children, Debra, David and Jim, and their spouses; nine grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog was born in New Athens, Illinois, a blue-collar community that would shape him long after he left. He excelled in baseball and basketball and was open to skipping the occasional class to take in a Cardinals game. Signed up by the Yankees, he was a center fielder who discovered that he had competition from a prospect born just weeks before him, Mickey Mantle.

Herzog never played for the Yankees, but he did get to know manager Casey Stengel, another master shuffler of players who became a key influence. The light-haired Herzog was named "The White Rat" because of his resemblance to Yankees pitcher Bob "The White Rat" Kuzava.

Like so many successful managers, Herzog was a mediocre player, batting just .257 over eight seasons and playing several positions. His best year was with Baltimore in 1961, when he hit .291. He also played for the Washington Senators, Kansas City Athletics and Detroit Tigers, with whom he ended his playing career, in 1963.

"Baseball has been good to me since I quit trying to play it," he liked to say.

After working as a scout and coach, Herzog was hired in 1967 by the New York Mets as director of player development, with Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan among the future stars he helped bring along. The Mets liked him well enough to designate him the successor to Gil Hodges, but when the manager died suddenly in 1972 the job went to Yogi Berra. Herzog instead debuted with the Texas Rangers the following season, finishing just 47-91 before being replaced by Billy Martin. He managed the Angels for a few games in 1974 and joined the Royals the following season, his time with Kansas City peaking in 1977 when the team finished 102-60.

Many players spoke warmly of Herzog, but he didn’t hesitate to rid his teams of those he no longer wanted, dumping such Cardinals stars as outfielder Lonnie Smith and starting pitcher Joaquin Andujar. One trade worked out brilliantly: Before the 1982 season, he exchanged .300 hitting shortstop Garry Templeton, whom Herzog had chastised for not hustling, for the Padres' light-hitting Ozzie Smith, now widely regarded as the best defensive shortstop in history. Another deal was less far successful: Gold Glove first baseman Keith Hernandez, with whom Herzog had feuded, to the Mets in the middle of 1983 for pitchers Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. Hernandez led New York to the World Series title in 1986, while Allen and Ownbey were soon forgotten.

Herzog was just as tough on himself, resigning in the middle of 1990 because he was “embarrassed” by the team’s 33-47 record. He served as a consultant and general manager for the Angels in the early '90s and briefly considered managing the Red Sox before the 1997 season.

If the '82 championship was the highlight of his career, his greatest blow was the '85 series. The Cardinals were up 3 games to 2 against his former team, the Royals, and in Game 6 led 1-0 going into the bottom of the ninth, with Worrell brought in to finish the job.

Jorge Orta led off and grounded a 0-2 pitch between the mound and first base. In one of the most famous blown calls in baseball history, he was ruled safe by umpire Don Denkinger, even though replays showed first baseman Jack Clark's toss to Worrell was in time. The Cardinals never recovered. Kansas City rallied for two runs to tie the series and crushed the Cards 11-0 in Game 7.

"No, I'm not bitter at Denkinger," Herzog told the AP years later. "He's a good guy, he knows he made a mistake, and he's a human being. It happened at an inopportune time but I do think they ought to have instant replay in the playoffs and World Series."

As if testing Herzog's humor, the Hall inducted him alongside an umpire, Doug Harvey.

"I don't know why he should get in," Herzog joked at the time. “Doug kicked me out of more games than any other umpire.”

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/MLB

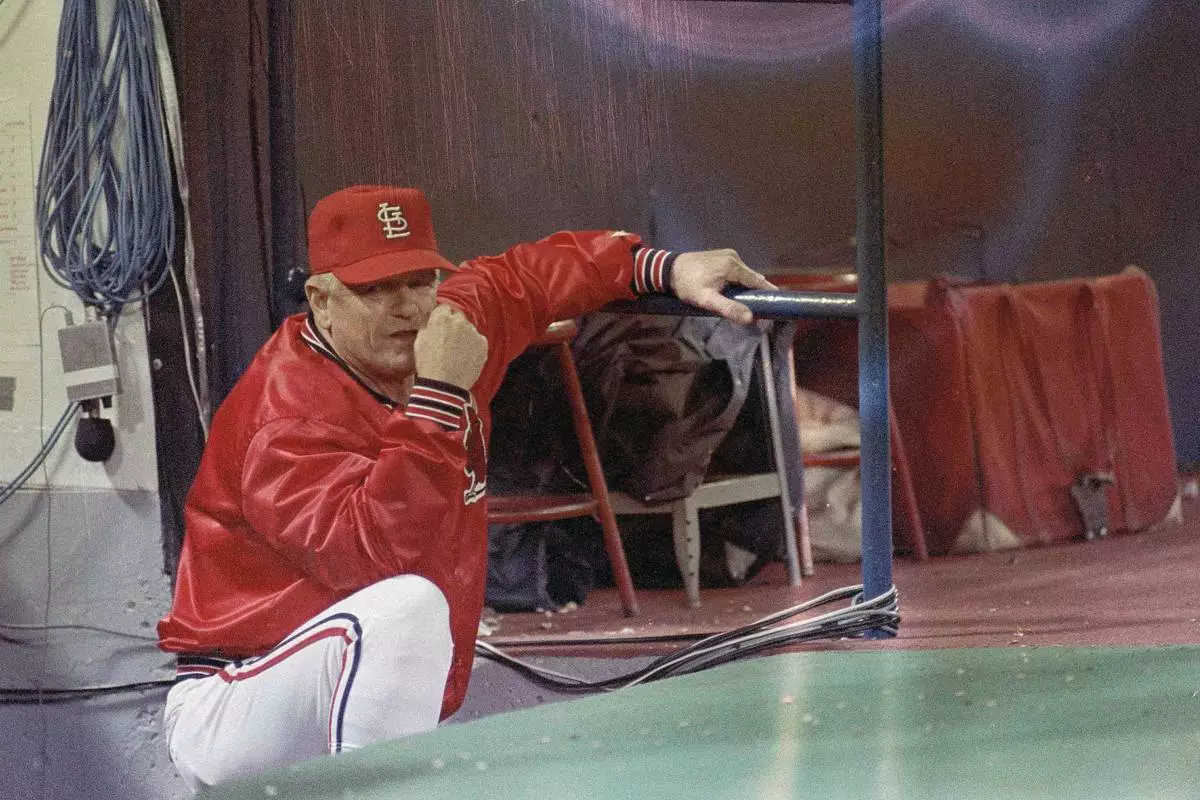

FILE - St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog watches during Game 7 of the World Series against the Kansas City Royals in Kansas City, Oct. 27, 1985. The Cardinals lost 11-0. Herzog, the gruff and ingenious Hall of Fame manager who guided the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and a World Series title in the 1980s and perfected an intricate, nail-biting strategy known as "Whiteyball," has died. He was 92. Cardinals spokesman Brian Bartow said Tuesday, April 16, 2024, the team had been informed of his death by Herzog's family.(AP Photo)

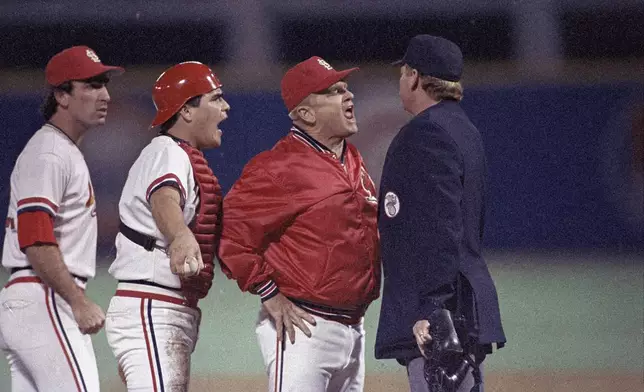

FILE - St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog lets umpire John Shulock, right, know how he feels about Shulock's call on the tag attempt on Kansas City Royals Jim Sundberg by Cardinals catcher Tom Nieto, second from left, in the second inning of Game 5 of the World Series in St. Louis, Mo., Oct. 24, 1985. Shulock had ruled Sundberg safe on the play. The Cardinal player at far left is unidentified.Herzog, the gruff and ingenious Hall of Fame manager who guided the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and a World Series title in the 1980s and perfected an intricate, nail-biting strategy known as "Whiteyball," has died. He was 92. Cardinals spokesman Brian Bartow said Tuesday, April 16, 2024, the team had been informed of his death by Herzog's family. (AP Photo/Peter Southwick, File)

FILE - Whitey Herzog delivers his Baseball Hall of Fame induction speech at the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, N.Y., on Sunday, July 25, 2010. Herzog, the gruff and ingenious Hall of Fame manager who guided the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and a World Series title in the 1980s and perfected an intricate, nail-biting strategy known as "Whiteyball," has died. He was 92. Cardinals spokesman Brian Bartow said Tuesday, April 16, 2024, the team had been informed of his death by Herzog's family.(AP Photo/Mike Groll, File)

FILE - Whitey Herzog, St. Louis Cardinals manager, in March 1987. Herzog, the gruff and ingenious Hall of Fame manager who guided the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and a World Series title in the 1980s and perfected an intricate, nail-biting strategy known as "Whiteyball," has died. He was 92. Cardinals spokesman Brian Bartow said Tuesday, April 16, 2024, the team had been informed of his death by Herzog's family. (AP Photo/Rusty Kennedy, File)

FILE - Former St. Louis Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog is seen before the start a baseball game between the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Mets Saturday, Aug. 19, 2023, in St. Louis. Herzog, the gruff and ingenious Hall of Fame manager who guided the St. Louis Cardinals to three pennants and a World Series title in the 1980s and perfected an intricate, nail-biting strategy known as "Whiteyball," has died. He was 92. Cardinals spokesman Brian Bartow said Tuesday, April 16, 2024, the team had been informed of his death by Herzog's family. (AP Photo/Jeff Roberson, File)