TANJUNGPINANG, Indonesia (AP) — Morwan Mohammad walks down an old hotel corridor on Batam Island in northwestern Indonesia before entering a 6-square-meter (64-square-foot) room that has been home to him and his growing family for the past eight years.

Mohammad, who fled war in Sudan, is one of hundreds of refugees living in community housing on the island while waiting for resettlement in a third country.

Click to Gallery

Rahima Farhangdost, an Afghan refugee who has been living in Indonesia since August 2014 after the Taliban banned her from working as a nurse and teacher, stands outside her boarding house in Bogor, Indonesia, Thursday, May 30, 2024. "I heard the process is faster and that after two or three years, we could get resettlement. So that's why I came to Indonesia. But it's been a very, very long time — 10 years now. I really regret it. I would prefer to die in Afghanistan, and not have come to Indonesia," she said. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Sudanese woman Rawda Yousif, who has been in Indonesia for eight years, stands for a photograph in her room at Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Hamid Mohammad, 28, an Afghan who has been in Indonesia for 11 years, looks into a mirror at a resort turned into a shelter for refugees, in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Indonesia, despite having a long history of accepting refugees, is not a signatory to the U.N. Refugee Convention of 1951 and its 1967 Protocol, and the government does not allow refugees and asylum-seekers to work.(AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Two of four Myanmarese fishermen, stranded because they cannot afford to pay for their onward travel, rest inside their cell at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

TANJUNGPINANG, Indonesia (AP) — Morwan Mohammad walks down an old hotel corridor on Batam Island in northwestern Indonesia before entering a 6-square-meter (64-square-foot) room that has been home to him and his growing family for the past eight years.

Rahima Farhangdost, an Afghan refugee who has been living in Indonesia since August 2014 after the Taliban banned her from working as a nurse and teacher, stands outside her boarding house in Bogor, Indonesia, Thursday, May 30, 2024. "I heard the process is faster and that after two or three years, we could get resettlement. So that's why I came to Indonesia. But it's been a very, very long time — 10 years now. I really regret it. I would prefer to die in Afghanistan, and not have come to Indonesia," she said. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Majdah Ishag, from Sudan, sits for a photograph in her room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Ishag has been at the community housing for eight years while waiting for resettlement in a third country. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Refugees talk outside a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Bintan, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Mohammad Khan Husaini, a 30-year-old Afghan who has been in Indonesia for 11 years, stands at a resort turned into a shelter in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Many refugees had fled to the sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago as a jumping-off point hoping to eventually reach Australia by boat, but are now stuck in what feels like an endless limbo. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Morwan Mohammad and his wife Nagad Daoud Abdallah, who fled war in Sudan, pose for a photograph in their room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. They are among hundreds of refugees living in community housing on the island while waiting for resettlement in a third country. All three of Mohammad's children were born in Indonesia and he does not know where his family will ultimately settle. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Sudanese woman Rawda Yousif, who has been in Indonesia for eight years, stands for a photograph in her room at Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

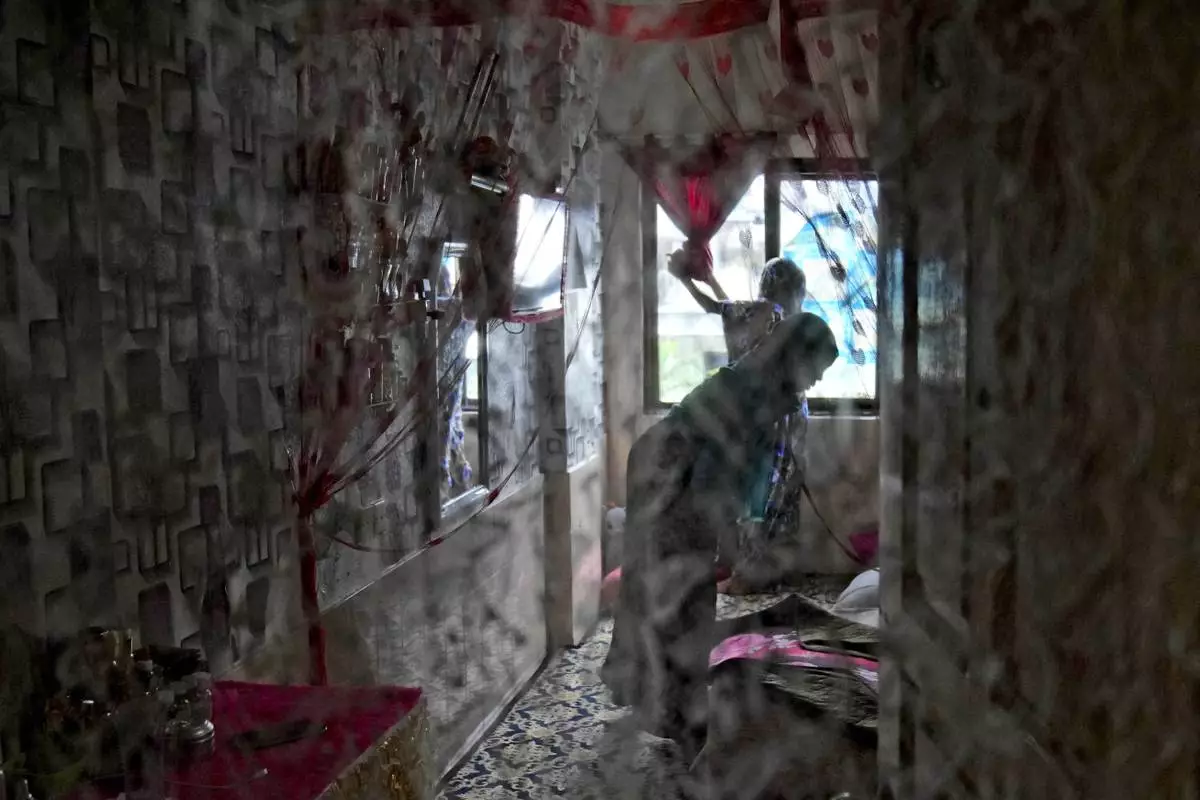

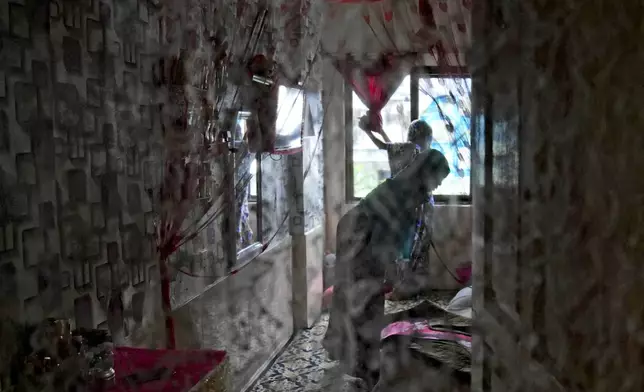

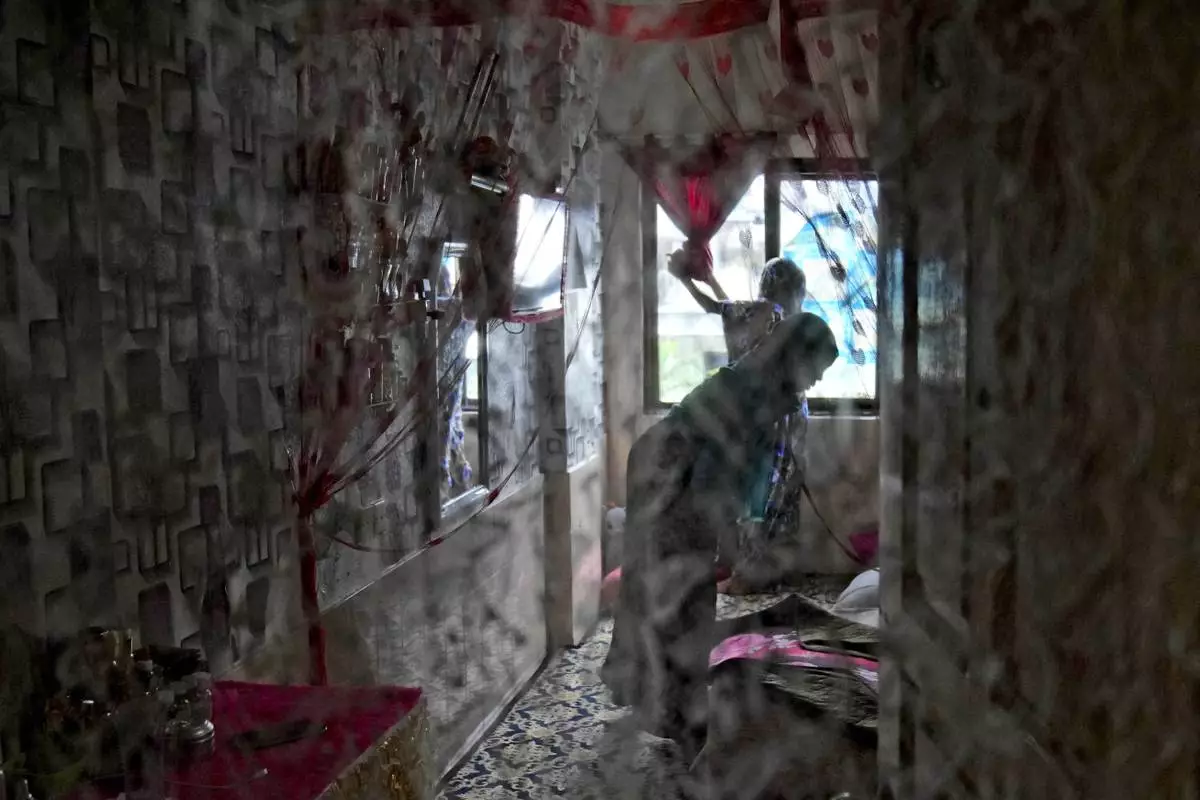

Majdah Ishag, a 36-year-old Sudanese woman, cleans up her room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Ishag has been living in the hotel for eight years after leaving home in search of a better life in Indonesia for her family. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Abdulnasir, a Somalian who has spent 8 years in Indonesia, stands at a resort turned into a shelter in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Many refugees had fled to the sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago as a jumping-off point hoping to eventually reach Australia by boat, but are now stuck in what feels like an endless limbo. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Hamid Mohammad, 28, an Afghan who has been in Indonesia for 11 years, looks into a mirror at a resort turned into a shelter for refugees, in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Indonesia, despite having a long history of accepting refugees, is not a signatory to the U.N. Refugee Convention of 1951 and its 1967 Protocol, and the government does not allow refugees and asylum-seekers to work.(AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Refugees walk outside Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Two of four Myanmarese fishermen, stranded because they cannot afford to pay for their onward travel, rest inside their cell at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

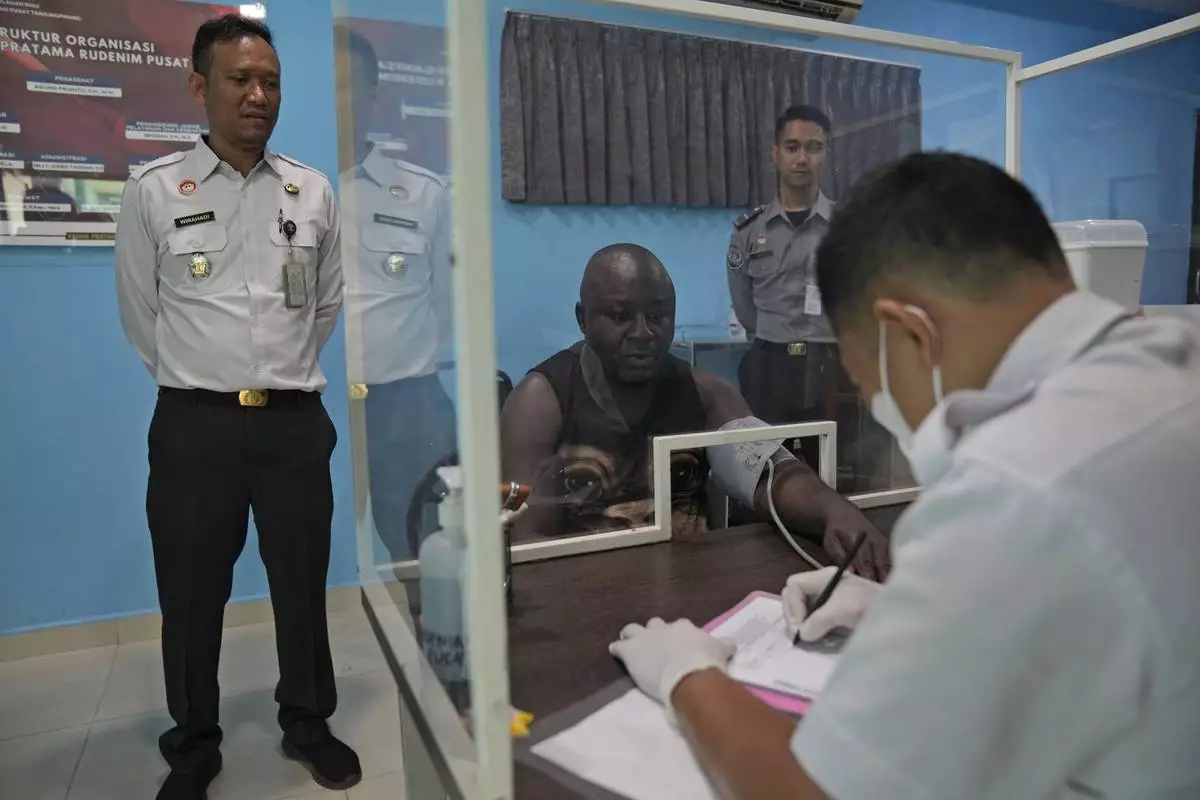

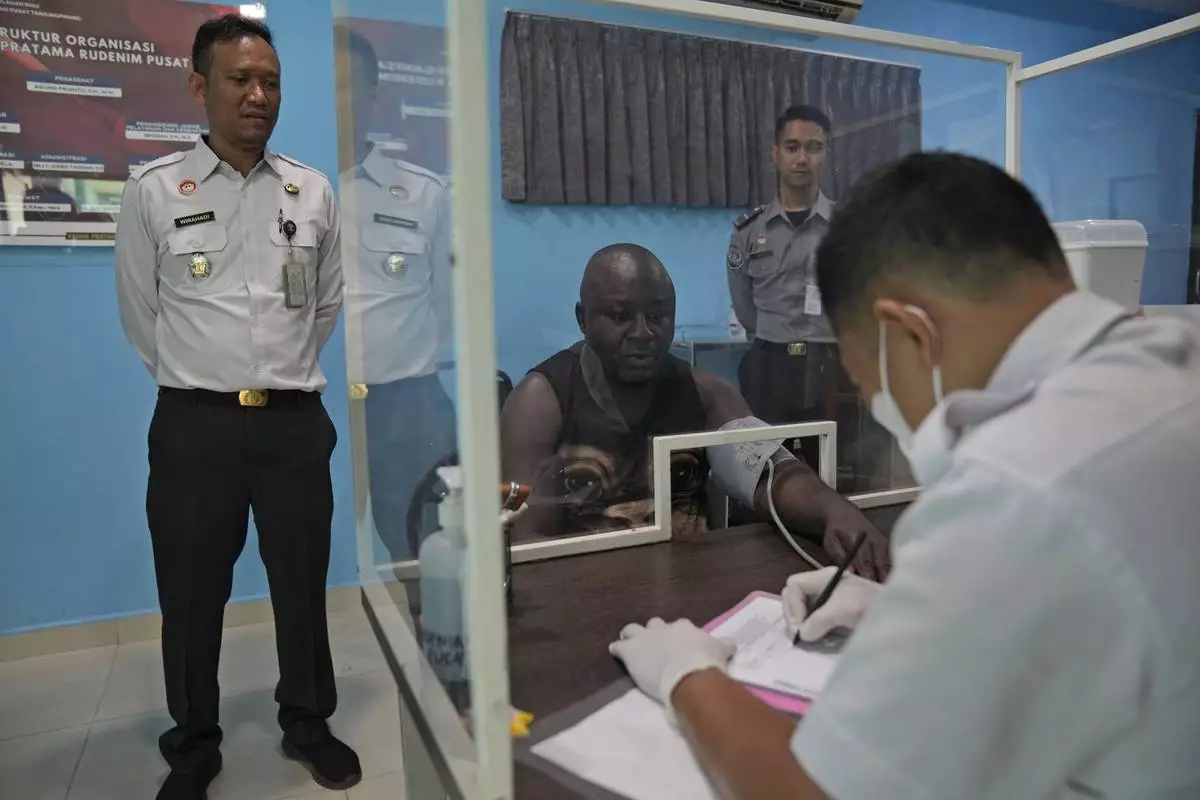

Officers check the health condition of a Nigerian detainee at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Detainees from Nigeria stand inside their cell at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

An Afghan refugee walks at a resort turned into a shelter in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Indonesia, despite having a long history of accepting refugees, is not a signatory to the U.N. Refugee Convention of 1951 and its 1967 Protocol, and the government does not allow refugees and asylum-seekers to work.(AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

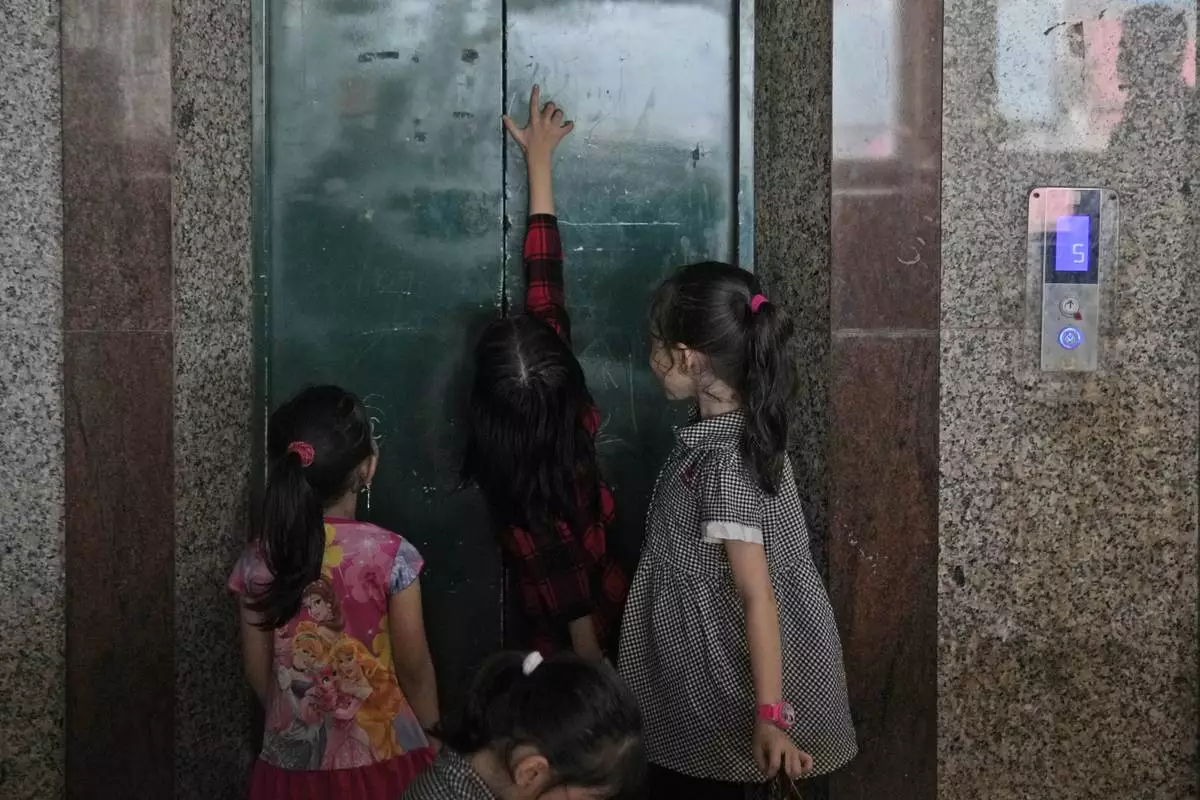

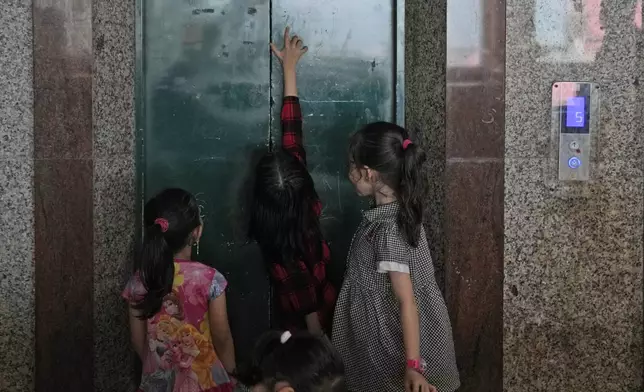

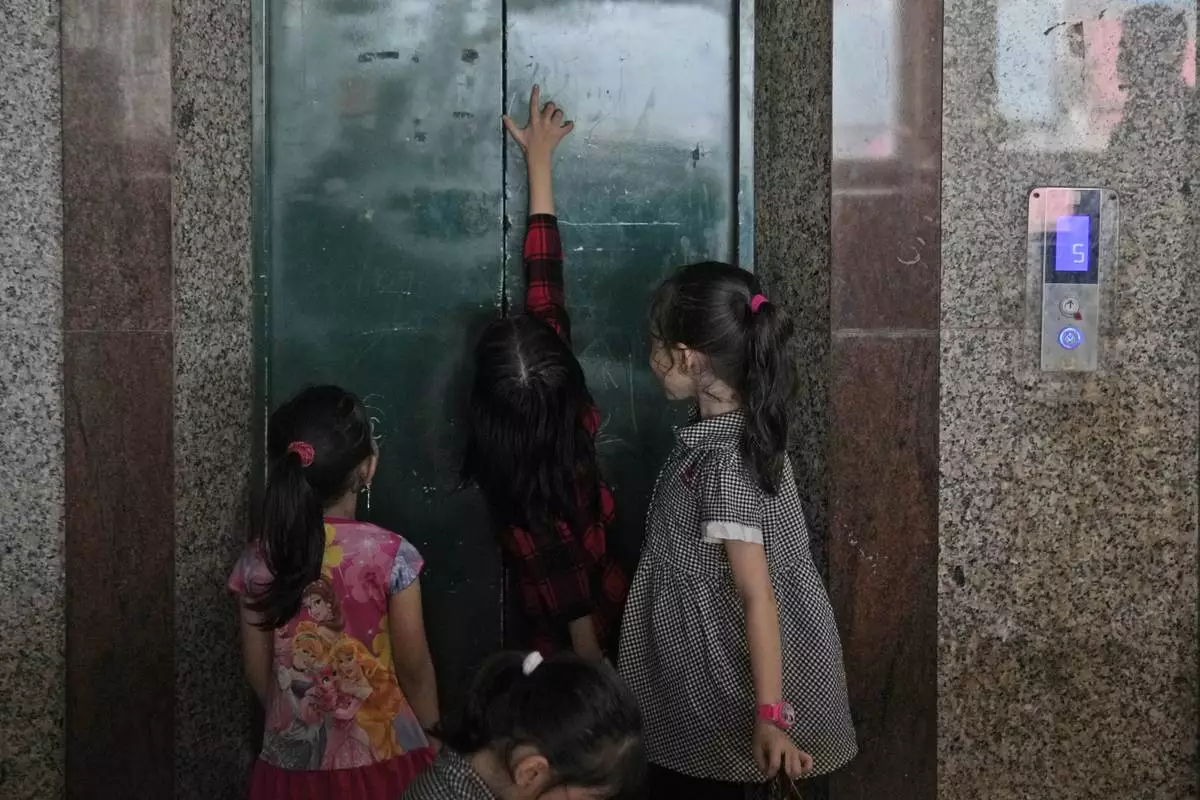

Children play near an elevator at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A refugee stands in front of what used to be the reception desk of Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A child plays with a mobile phone in the hallway of Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Nagad Daoud Abdallah, right, and Majdah Ishag, both from Sudan, sit on a bed in Ishag's room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Both have been at the community housing for eight years while waiting for resettlement in a third country. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Hotel Kolekta, a former tourist hotel, was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. The island, just south of Singapore, has a population of 1.2 million people.

Indonesia, despite having a long history of accepting refugees, is not a signatory to the U.N. Refugee Convention of 1951 and its 1967 Protocol, and the government does not allow refugees and asylum-seekers to work.

Many had fled to Indonesia as a jumping-off point hoping to eventually reach Australia by boat, but are now stuck in what feels like an endless limbo.

Mohammad and his wife arrived in Jakarta nine years ago after traveling from his hometown Nyala to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and onward to the sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago, where their first stop was the U.N. refugee agency office in the capital.

“We did not know where to go — just looking for a safe place to live. The most important thing was to get out of Sudan to avoid war,” he said.

They made their way to Batam in 2016, believing it would be easier to travel from there to a third country for resettlement.

All three of Mohammad’s children were born in Indonesia and he does not know where his family will ultimately settle. He says he wants to have a normal life, working and earning money so he can support himself without relying on others for assistance.

“We left our country, our family. We miss our family members. But life here is also too hard for us because for eight years we are not working, not doing good activities. Just sleep, wake up, eat, repeat,” he said.

Hotel Kolekta is administered by the Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on nearby Bintan Island. That three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing similarly uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, but in conditions that more closely resemble a prison.

Two Palestinian men have languished there for over a year, unable to return home due to the ongoing war in Gaza. Four Burmese fishermen are stranded because they cannot afford to pay for their onward travel.

Those held in the detention center typically violated Indonesia’s immigration regulations, while those living in Hotel Kolekta and other community housing entered the country legally seeking safe haven.

On Batam Island, Majdah Ishag, a 36-year-old Sudanese woman, has been living in the hotel for eight years after leaving home in search of a better life in Indonesia for her family. Her daily needs are met but she worries about the future and doesn’t want her five children to spend their entire lives in Hotel Kolekta.

“I hope I can find work and resettlement,” she said.

The UNHCR office in Indonesia says that nearly one-third of the 12,295 people registered with organization are children who have limited access to education and health services.

Rahima Farhangdost is one of 5,732 refugees from Afghanistan stranded in Indonesia. She lives in Bogor, 60 kilometers (37 miles) from Jakarta, and has been in Indonesia since August 2014 after the Taliban banned her from working as a nurse and teacher in her hometown in the country’s southeast.

For five years, she received money from a cousin in Afghanistan, but that relative died in conflict and she has since had to receive monthly financial support from UNHCR.

“I heard the process is faster and that after two or three years, we could get resettlement. So that’s why I came to Indonesia. But it’s been a very, very long time — 10 years now. I really regret it. I would prefer to die in Afghanistan, and not have come to Indonesia,” she said.

UNHCR Indonesia says more than 12,000 individuals from 40 countries in the country are listed as refugees under Indonesian law, most of them from Afghanistan.

Ann Maymann, a UNHCR representative in Indonesia, said: “Resettlement is not speedy ... because it is not the UNHCR who decides. We cannot decide that a refugee will go to this country.”

Maymann said refugees under the current system cannot be assured of a better future in Indonesia, especially those who will not be resettled.

“That is exactly why we need to work on improving the conditions for the refugees while they are in Indonesia, because resettlement cannot be the only solution. Because it is not the only solution. Because not all will be resettled,” Maymann said.

Tarigan reported from Jakarta.

Refugees talk outside a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Bintan, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Many refugees had fled to the sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago as a jumping-off point hoping to eventually reach Australia by boat, but are now stuck in what feels like an endless limbo. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Rahima Farhangdost, an Afghan refugee who has been living in Indonesia since August 2014 after the Taliban banned her from working as a nurse and teacher, stands outside her boarding house in Bogor, Indonesia, Thursday, May 30, 2024. "I heard the process is faster and that after two or three years, we could get resettlement. So that's why I came to Indonesia. But it's been a very, very long time — 10 years now. I really regret it. I would prefer to die in Afghanistan, and not have come to Indonesia," she said. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Majdah Ishag, from Sudan, sits for a photograph in her room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Ishag has been at the community housing for eight years while waiting for resettlement in a third country. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Refugees talk outside a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Bintan, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Mohammad Khan Husaini, a 30-year-old Afghan who has been in Indonesia for 11 years, stands at a resort turned into a shelter in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Many refugees had fled to the sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago as a jumping-off point hoping to eventually reach Australia by boat, but are now stuck in what feels like an endless limbo. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Morwan Mohammad and his wife Nagad Daoud Abdallah, who fled war in Sudan, pose for a photograph in their room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. They are among hundreds of refugees living in community housing on the island while waiting for resettlement in a third country. All three of Mohammad's children were born in Indonesia and he does not know where his family will ultimately settle. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Sudanese woman Rawda Yousif, who has been in Indonesia for eight years, stands for a photograph in her room at Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Majdah Ishag, a 36-year-old Sudanese woman, cleans up her room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Ishag has been living in the hotel for eight years after leaving home in search of a better life in Indonesia for her family. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Abdulnasir, a Somalian who has spent 8 years in Indonesia, stands at a resort turned into a shelter in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Many refugees had fled to the sprawling Southeast Asian archipelago as a jumping-off point hoping to eventually reach Australia by boat, but are now stuck in what feels like an endless limbo. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Hamid Mohammad, 28, an Afghan who has been in Indonesia for 11 years, looks into a mirror at a resort turned into a shelter for refugees, in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Indonesia, despite having a long history of accepting refugees, is not a signatory to the U.N. Refugee Convention of 1951 and its 1967 Protocol, and the government does not allow refugees and asylum-seekers to work.(AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Refugees walk outside Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Two of four Myanmarese fishermen, stranded because they cannot afford to pay for their onward travel, rest inside their cell at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Officers check the health condition of a Nigerian detainee at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Detainees from Nigeria stand inside their cell at Tanjungpinang Central Immigration Detention Center on Bintan Island, Indonesia, Wednesday, May 15, 2024. This three-story detention facility, with its barred windows and fading paint, is home to dozens of detainees facing uncertain futures, including whether they will ever return to their homelands, in conditions that closely resemble a prison. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

An Afghan refugee walks at a resort turned into a shelter in Tanjungpinang, Bintan Island, Indonesia, Tuesday, May 14, 2024. Indonesia, despite having a long history of accepting refugees, is not a signatory to the U.N. Refugee Convention of 1951 and its 1967 Protocol, and the government does not allow refugees and asylum-seekers to work.(AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Children play near an elevator at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A refugee stands in front of what used to be the reception desk of Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A child plays with a mobile phone in the hallway of Hotel Kolekta, turned into a shelter for refugees, in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. The former tourist hotel was converted in 2015 into a temporary shelter that today houses 228 refugees from conflict-torn nations including Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Nagad Daoud Abdallah, right, and Majdah Ishag, both from Sudan, sit on a bed in Ishag's room at a hotel turned into a shelter for refugees in Batam, an island in northwestern Indonesia, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Both have been at the community housing for eight years while waiting for resettlement in a third country. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A jury found a suburban Seattle police officer guilty of murder Thursday in the 2019 shooting death of a homeless man outside a convenience store, marking the first conviction under a Washington state law easing prosecution of law enforcement officers for on-duty killings.

After deliberating for three days, the jury found Auburn Police Officer Jeffrey Nelson guilty of second-degree murder and first-degree assault for shooting Jesse Sarey twice while trying to arrest him for disorderly conduct. Deliberations had been halted for several hours Wednesday after the jury sent the judge an incomplete verdict form Tuesday saying they were unable to reach an agreement on one of the charges.

The judge revealed Thursday that the verdict the jury was struggling with earlier in the week was the murder charge. They had already reached agreement on the assault charge.

Nelson was taken into custody after the hearing. He's been on paid administrative leave since the shooting in 2019. The judge set sentencing for July 16. Nelson faces up to life in prison on the murder charge and up to 25 years for first-degree assault. His lawyer said she plans to file a motion for a new trial.

Elaine Simons, who had been Sarey's foster mother, said the guilty verdicts provided resolution and peace for his family.

“This has been a long five years for a semblance of justice,” she told The Associated Press. “It has set a precedent for police officers to do what is right. The citizens of Auburn can have a sense of safety.”

Gary Damon, executive director of the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, a group led by families who have lost loved ones to police violence, said the verdict was a significant step toward greater accountability for officers. Leslie Cushman, who was involved in the campaign to change the state's law to make it easier to charge officers, said the trial was profoundly important.

“Had this gone the other way, we would have had a serious disillusionment,” Cushman said. “This is good news and affirming for all who stand for justice.”

The King County Prosecuting Attorney's office thanked the jury for their efforts on the case, which has gone on for more than three weeks.

“We appreciate the hard work of all parties to get to these important verdicts,” spokesman Casey McNerthney said in an email. “All along we felt this was a case that needed to be tried before a jury. Our thoughts continue to be with Mr. Sarey’s loved ones.”

Prosecutors said Nelson punched Sarey several times before shooting him in the abdomen. About three seconds later, Nelson shot Sarey in the forehead. Nelson had claimed Sarey tried to grab his gun and a knife, so he shot him in self-defense, but video showed Sarey was on the ground reclining away from Nelson after the first shot.

The case was the second to go to trial since Washington voters in 2018 removed a standard that required prosecutors to prove an officer acted with malice — a standard no other state had. Now they must show the level of force was unreasonable or unnecessary. In December, jurors acquitted three Tacoma police officers in the 2020 death of Manuel Ellis.

Nelson had responded to reports of a man throwing things at cars, kicking walls and banging on windows in a shopping area in Auburn, a city of 70,000 about 28 miles (45 kilometers) south of Seattle. Callers said the man appeared to be high or having mental health issues.

Sarey was the son of survivors of the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia and became homeless after aging out of foster care, his family said.

Nelson confronted Sarey in front of the store and attempted to get him into handcuffs. When Sarey resisted, Nelson tried to take Sarey down with a hip-throw and then punched him seven times. He pinned Sarey against the wall, pulled out his gun and shot him. Sarey fell to the ground.

Nelson’s gun jammed, he cleared it, looked around and then aimed at Sarey’s forehead, firing once more.

A witness, Steven Woodard, testified that after the first shot, “Mr. Sarey was ‘done,’ lying on the ground in a nonthreatening position.”

Nelson claimed Sarey tried to grab his gun, leading to the first shot. He said he believed Sarey had possession of his knife during the struggle and said he shot him in self-defense. Authorities have said the interaction lasted 67 seconds.

“Jesse Sarey died because this defendant chose to disregard his training at every step of the way,” King County Special Prosecutor Patty Eakes told the jury in her closing argument Thursday. The shooting was “unnecessary, unreasonable and unjustified,” she said.

Nelson’s attorney, Kristen Murray, told the jury officers are allowed to defend themselves.

“When Mr. Sarey went for Officer Nelson’s gun, he escalated it to a lethal encounter,” she said.

Auburn settled a civil rights claim by Sarey’s family for $4 million and has paid nearly $2 million more to settle other litigation over Nelson’s actions as a police officer.

Sarey was the third person Nelson has killed in his law enforcement career. Jurors did not hear evidence about Nelson’s prior uses of deadly force.

Prior to fatally shooting Sarey, Nelson killed Isaiah Obet in 2017. Obet was acting erratically, and Nelson ordered his police dog to attack. He then shot Obet in the torso. Obet fell to the ground, and Nelson fired again, fatally shooting Obet in the head. Police said the officer’s life was in danger because Obet was high on drugs and had a knife. The city reached a settlement of $1.25 million with Obet’s family.

In 2011, Nelson fatally shot Brian Scaman, a Vietnam War veteran with mental issues and a history of felonies, after pulling Scaman’s vehicle over for a burned-out headlight. Scaman got out of his car with a knife and refused to drop it; Nelson shot him in the head. An inquest jury cleared Nelson of wrongdoing.

Jeffrey Nelson, flanked by attorneys, stands at the King County Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash., on Thursday, June 27, 2024. A jury found the suburban Seattle police officer guilty of murder in the 2019 shooting death of a homeless man outside a convenience store, marking the first conviction under a Washington state law easing prosecution of law enforcement officers for on-duty killings. (Kevin Clark/The Seattle Times via AP)

Jeffrey Nelson, flanked by attorneys, stands at the King County Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash., on Thursday, June 27, 2024. A jury found the suburban Seattle police officer guilty of murder in the 2019 shooting death of a homeless man outside a convenience store, marking the first conviction under a Washington state law easing prosecution of law enforcement officers for on-duty killings. (Kevin Clark/The Seattle Times via AP)

FILE - Auburn Police Officer Jeffrey Nelson, center, and defense attorney Tim Leary, behind, attend closing arguments, Thursday, June 20, 2024, at Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash. A jury found the suburban Seattle police officer guilty of murder Thursday, June 27, in the 2019 shooting death of a homeless man outside a convenience store, marking the first conviction under a Washington state law easing prosecution of law enforcement officers for on-duty killings. (Erika Schultz/The Seattle Times via AP, File)

FILE - Auburn Police Officer Jeffrey Nelson, center, attends closing arguments in his trial, Thursday, June 20, 2024, at the Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash. A jury found the suburban Seattle police officer guilty of murder Thursday, June 27, in the 2019 shooting death of a homeless man outside a convenience store, marking the first conviction under a Washington state law easing prosecution of law enforcement officers for on-duty killings. (Erika Schultz/The Seattle Times via AP, File)

Jeffrey Nelson awaits the jury's verdict at the King County Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash., on Thursday, June 27, 2024. (Kevin Clark/The Seattle Times via AP)

Auburn Police Officer Jeffrey Nelson is taken into custody after two guilty verdicts were headed down by the jury Thursday at the King County Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash., on Thursday, June 27, 2024. Nelson was found guilty of second-degree murder and first-degree assault for shooting Jesse Sarey twice while trying to arrest him for disorderly conduct. (Kevin Clark/The Seattle Times via AP)

Auburn Police Officer Jeffrey Nelson, center, and defense attorney Tim Leary, behind, attend closing arguments at Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash., Thursday, June 20, 2024. Officer Nelson is charged with fatally shooting Jesse Sarey, 26, while attempting to arrest him for disorderly conduct on May 31, 2019. (Erika Schultz/The Seattle Times via AP)

Auburn Police Officer Jeffrey Nelson, center, attends closing arguments in his trial, Thursday, June 20, 2024, at the Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent, Wash. Officer Nelson is charged with fatally shooting Jesse Sarey, 26, while attempting to arrest him for disorderly conduct on in 2019. (Erika Schultz/The Seattle Times via AP)