VINEYARD HAVEN, Mass. (AP) — Sheryl Taylor works as an administrator for Martha's Vineyard Regional High School. Each summer, she has to leave the island or stay with friends because she can't afford the high seasonal rents.

How high? The average vacation home rents for $6,500 a week.

Click to Gallery

VINEYARD HAVEN, Mass. (AP) — Sheryl Taylor works as an administrator for Martha's Vineyard Regional High School. Each summer, she has to leave the island or stay with friends because she can't afford the high seasonal rents.

Jason Merrill, owner of Martha's Vineyard Bike Rentals, poses outside his store, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Edgartown, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

People walk dogs in front of homes, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Brick sidewalks line homes in Edgartown, Mass., Tuesday, June 4, 2024. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

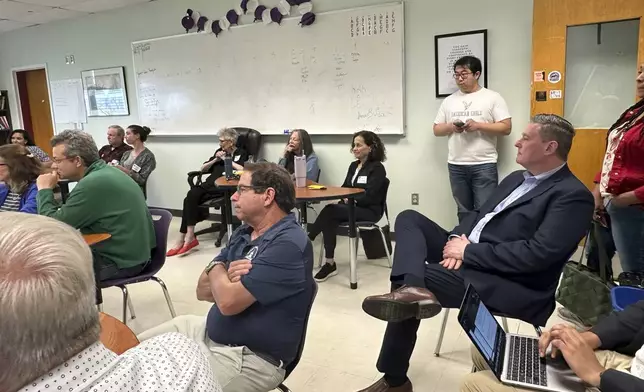

Ed Augustus, seated, right, the Massachusetts State Secretary of Housing and Livable Communities, listens to concerns about housing during an event at the Martha's Vineyard Regional High School, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Ed Augustus, center, the Massachusetts State Secretary of Housing and Livable Communities, listens to concerns about housing during an event at the Martha's Vineyard Regional High School, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Martha's Vineyard Regional High School administrator Sheryl Taylor, left, poses with her daughter Leelyn Thompson at the school on Tuesday June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

“I have spent a significant amount of time couch surfing,” said Taylor, the school’s equity and access coordinator. “With my suitcase in my car, and moving one or two nights here and there with friends on the island.”

Taylor’s plight reflects that of many on the Massachusetts island off Cape Cod. There are plenty of jobs, but restaurants and stores often can’t find enough staff because workers can't afford to live there. Officials worry public safety is being compromised because they can’t retain or lure correctional officers or 911 dispatchers.

Landlords stand to make far more money from short-term tourists than from year-round residents. Meanwhile, many island homes remain almost permanently vacant, their wealthy owners uninterested in renting them out between fleeting visits.

A new report lays out in stark terms just how many low- and middle-income folks are being forced to move away from Martha's Vineyard as its popularity with wealthy vacationers soars, causing the year-round population of 20,000 to swell up to tenfold over summer.

In 2012, 40% of islanders earned less than $50,000 a year, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission housing report found. Ten years later, the figure had dropped to 23%. The proportion of people earning between $50,000 and $100,000 also fell over that time, while those earning more than $100,000 almost doubled to 46%.

“So we’ve had a shift in our income distribution. This speaks to the fact that we’re losing year-round residents," said Laura Silber, the island housing planner who wrote the report. "We’re losing our low- and moderate-income families. We’re losing our middle class, because we have no housing.”

The report shows the average nightly rate among more than 3,000 short-term rentals is $931. And the average home price has more than doubled over the past 11 years to $2.3 million. Nearby Nantucket island is even more extreme, with the median home price reaching $3.55 million.

Dukes County Sheriff Robert Ogden said the cost of housing has become a public safety issue on Martha's Vineyard, with his agency unable to maintain the 11 or so 911 operators it needs to provide lifesaving information over the phone, such as CPR instructions. Operators who stay often get burned out from working too much overtime, he said.

“It's a vicious cycle," Ogden said. “Every year, we're losing two to three dispatchers because of not only the high cost of living here, but the insecurity of housing.”

One trained correctional officer, he said, was forced to instead take cleaning jobs so she didn't earn too much and lose her access to low-income housing.

“Can you imagine, in any society, where you would say that I pay someone too much to stay on the job?" Ogden said. “How insane is that?”

Ogden said he has been involved in an effort over the past six years to try to impose a local tax on home sales to help pay for affordable housing on the island, but it still requires new state legislation.

Jason Merrill, who owns the Martha’s Vineyard Bike Rentals store, said people will often stop to ask him if he’s heard of any jobs that come with housing, or any housing options at all.

“It’s definitely a point of contention here in the towns, and town hall meetings, that Airbnb is taking over," Merrill said.

Many workers, like painting laborer Abelardo Neto, can afford to stay on the island only by cramming together. He said he lives in a place with seven people. They each pay $850 a month in rent.

Olda Deda, an Albanian visiting on a student work visa, said she works three jobs — at a coffee shop and two restaurants — and a big chunk of her wages goes toward her $900 monthly rent. It's about three times higher than she would expect to pay in Europe, she said, and the housing costs came as a shock to her and many other seasonal workers.

Ed Augustus, the state’s secretary of housing and livable communities, visited Martha's Vineyard this month to hear directly from residents.

“We’ve heard examples of folks who are coming in on the ferry every single day, sometimes from Falmouth, sometimes from further locations on the cape, sometimes from off cape,” Augustus said. The extra costs and time for travel are making jobs on the island less appealing or cost-effective.

A sweeping housing bill that was approved by the state House this month would help, Augustus said. The bill contains $6.5 billion in bond authorizations, tax credits and policy initiatives and is aimed at supercharging the creation and renovation of affordable housing. Building on proposed legislation unveiled last year by Democratic Gov. Maura Healey, the bill still needs to be approved by the Senate.

Until then, people like Taylor will need to keep figuring out how to survive the housing challenge. She pays a huge amount to be at the school for a required two weeks over summer, she said, then come fall she faces all the costs associated with moving into a new rental.

A home sits on a freshly mowed lawn in Edgartown, Mass., Tuesday, June 4, 2024. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Jason Merrill, owner of Martha's Vineyard Bike Rentals, poses outside his store, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Edgartown, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

People walk dogs in front of homes, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Brick sidewalks line homes in Edgartown, Mass., Tuesday, June 4, 2024. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Ed Augustus, seated, right, the Massachusetts State Secretary of Housing and Livable Communities, listens to concerns about housing during an event at the Martha's Vineyard Regional High School, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Ed Augustus, center, the Massachusetts State Secretary of Housing and Livable Communities, listens to concerns about housing during an event at the Martha's Vineyard Regional High School, Tuesday, June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

Martha's Vineyard Regional High School administrator Sheryl Taylor, left, poses with her daughter Leelyn Thompson at the school on Tuesday June 4, 2024, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts. High housing costs on Martha's Vineyard are forcing many regular workers to leave and are threatening public safety. (AP Photo/Nick Perry)

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Environmental Protection Agency will not be able to enforce a key rule limiting air pollution in nearly a dozen states while separate legal challenges proceed around the country, under a Supreme Court decision Thursday.

The EPA’s “good neighbor” rule is intended to restrict smokestack emissions from power plants and other industrial sources that burden downwind areas with smog-causing pollution.

Three energy-producing states — Ohio, Indiana and West Virginia — challenged the rule, along with the steel industry and other groups, calling it costly and ineffective.

The Supreme Court put the rule on hold while legal challenges continue, the conservative-led court’s latest blow to federal regulations.

The high court, with a 6-3 conservative majority, has increasingly reined in the powers of federal agencies, including the EPA, in recent years. The justices have restricted EPA’s authority to fight air and water pollution, including a landmark 2022 ruling that limited EPA’s authority to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants that contribute to global warming.

The court is also weighing whether to overturn its 40-year-old Chevron decision, which has been the basis for upholding a wide range of regulations on public health, workplace safety and consumer protections.

A look at the good neighbor rule and the implications of the court decision.

The EPA adopted the rule as a way to protect downwind states that receive unwanted air pollution from other states. Besides the potential health impacts from out-of-state pollution, many states face their own federal deadlines to ensure clean air.

States such as Wisconsin, New York and Connecticut said they struggle to meet federal standards and reduce harmful levels of ozone because of pollution from out-of-state power plants, cement kilns and natural gas pipelines that drift across their borders.

Ground-level ozone, commonly known as smog, forms when industrial pollutants emitted by cars, power plants, refineries and other sources chemically react in the presence of sunlight. High ozone levels can cause respiratory problems, including asthma and chronic bronchitis. People with compromised immune systems, the elderly and children playing outdoors are particularly vulnerable.

Judith Vale, New York’s deputy solicitor general, told the court that for some states, as much as 65% of smog pollution comes from outside its borders.

States that contribute to ground-level ozone must submit plans ensuring that coal-fired power plants and other industrial sites do not add significantly to air pollution in other states. In cases where a state has not submitted a “good neighbor” plan — or where EPA disapproves a state plan — a federal plan is supposed to ensure downwind states are protected.

The Supreme Court decision blocks EPA enforcement of the rule and sends the case back to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which is considering a lawsuit challenging the regulation that was brought by 11 mostly Republican-leaning states.

An EPA spokesman said the agency believes the plan is firmly rooted in its authority under the Clean Air Act and “looks forward to defending the merits of this vital public health protection" before that appeals court.

The spokesman, Timothy Carroll, said the Supreme Court's ruling will "postpone the benefits that the Good Neighbor Plan is already achieving in many states and communities.''

While the plan is on pause, "Americans will continue to be exposed to higher levels of ground-level ozone, resulting in costly public health impacts that can be especially harmful to children and older adults,'' Carroll said. Ozone disproportionately affects people of color, families with low incomes, and other vulnerable populations, he said.

Rich Nolan, president and CEO of the National Mining Association, said he was pleased that the Supreme Court "recognized the immediate harm to industry and consumers posed by this reckless rule. No agency is permitted to operate outside of the clear bounds of the law and today, once again, the Supreme Court reminded the EPA of that fact.''

With a stay in place, Nolan said the mining industry looks forward to making its case in court that the EPA rule “is unlawful in its excessive overreach and must be struck down to protect American workers, energy independence, the electric grid and the consumers it serves,.”

The EPA rule was intended to provide a national solution to the problem of ozone pollution, but challengers said it relied on the assumption that all 23 states targeted by the rule would participate. In fact, only about half that number of states were participating as of early this year.

A lawyer for industry groups that are challenging the rule said it imposes significant and immediate costs that could affect the reliability of the electric grid. With fewer states participating, the rule may result in only a small reduction in air pollution, with no guarantee the final rule will be upheld, industry lawyer Catherine Stetson told the Supreme Court in oral arguments earlier this year.

The EPA has said power-plant emissions dropped by 18% in 2023 in the 10 states where it has been allowed to enforce its rule, which was finalized last year. Those states are Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Wisconsin. In California, limits on emissions from industrial sources other than power plants are supposed to take effect in 2026.

The rule is on hold in another dozen states because of separate legal challenges. The states are Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and West Virginia.

Critics, including Republicans and business groups, call the good neighbor rule an example of government overreach.

The EPA rule and other Biden administration regulations “are designed to hurriedly rid the U.S. power sector of fossil fuels by sharply increasing the operating costs, ... forcing the plants’ premature retirement,” Republican lawmakers said in a brief filed with the high court.

Supporters disputed that and called the "good neighbor'' rule critical to address interstate air pollution and ensure that all Americans have access to clean air.

“Today’s move by far-right Supreme Court justices to stay commonsense clean air rules shows just how radical this court has become,'' said Charles Harper of environmental group Evergreen Action.

“The court is meddling with a rule that would prevent 1,300 Americans from dying prematurely every year from pollution that crosses state borders. We know that low-income and disadvantaged communities with poor air quality will bear the brunt of this delay,'' Harper said.

Roger Reynolds, senior legal director of the environmental group Save the Sound, said the decision hinders the EPA from protecting states such as Connecticut and New York that suffer from ozone pollution generated in the Midwest.

"We cannot reach healthy air quality for our residents without addressing upwind pollution, in addition to local sources,” Reynolds said.

The rule applies mostly to states in the South and Midwest that contribute to air pollution along the East Coast. Some states, such as Texas, California, Pennsylvania, Illinois and Wisconsin, both contribute to downwind pollution and receive it from other states.

Associated Press writer Susan Haigh in Hartford, Connecticut contributed to this story.

FILE - Emissions rise from smokestacks at the Jeffrey Energy Center coal power plant, near Emmett, Kan., Sept. 18, 2021. The Supreme Court decided Thursday, June 27, 2924, that the EPA won't be able to enforce a key rule limiting air pollution in nearly a dozen states while separate legal challenges proceed around the country. The EPA's "good neighbor" rule is intended to restrict smokestack emissions from power plants and other industrial sources that burden downwind areas with smog-causing pollution.Ohio, Indiana and West Virginia challenged the rule, along with the steel industry and other groups. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel, File)

The Supreme Court building is seen, Wednesday, June 26, 2024, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

People walk past the Supreme Court on Thursday, June 27, 2024, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)