Robin Alderman faces an agonizing reality: Gene therapy might cure her son Camden’s rare, inherited immune deficiency. But it’s not available to him.

In 2022, London-based Orchard Therapeutics stopped investing in an experimental treatment for the condition, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. And there are no gene therapy studies he can join.

“We feel like we are the forgotten,” said Alderman, who's advocated for her 21-year-old son since he was a baby.

Collectively, about 350 million people worldwide suffer from rare diseases, most of which are genetic. But each of the 7,000 individual disorders affects perhaps a few in a million people or less. There’s little commercial incentive to develop or bring to market these one-time therapies to fix faulty genes or replace them with healthy ones. This leaves families like the Aldermans scrambling for help and some trying to raise money themselves for cures that may never come.

“These kids have been unfortunate twice: A, because they got a genetic disease, and B, because the disease is so rare that nobody cares,” said Dr. Giulio Cossu, a professor of regenerative medicine at the University of Manchester in England. “Companies want to make a profit.”

Scientists say this dynamic threatens to thwart progress in the nascent gene therapy field, erasing the potential of a new type of medicine just as a steady stream of research points toward promising treatments for various disorders. Researchers are seeking solutions, often turning to charitable organizations, patient groups and governments.

A major Italian charity announced in February that it’s taking over the Wiskott-Aldrich treatment Orchard had been pursuing. And an arm of the charitable Foundation Fighting Blindness helped launch a company, Opus Genetics, to advance gene therapy work by University of Pennsylvania researcher Dr. Jean Bennett and a colleague.

In many ways, that effort was inspired by patients' families.

“Some of them have bake sales. One family mortgaged their house to give some money for a study for their rare disease,” Bennett said. “I just feel responsible to help them.”

The Aldermans have faced years of pain and frustration.

Camden Alderman was diagnosed as a baby with Wiskott-Aldrich, caused by a mutated gene on the X chromosome. It primarily affects boys – up to 10 out of every million — and can cause frequent infections, eczema and excessive bleeding.

When he was a toddler, doctors removed his spleen because of uncontrolled bleeding. As a young boy, he wound up in the hospital many times and was told he couldn't play baseball.

One treatment is a bone marrow transplant. But he is Black and has Korean heritage, making it difficult to find a donor — people are most likely to match with someone of similar ancestral or ethnic backgrounds. Robin Alderman recalls one doctor saying: “Basically, your son’s only chance at a cure is going to be gene therapy.”

He also told her researchers weren’t then accepting U.S. residents into a clinical trial, which “just kind of broke my heart,” she said.

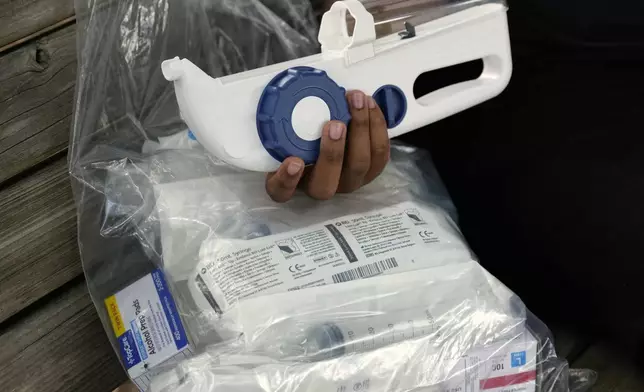

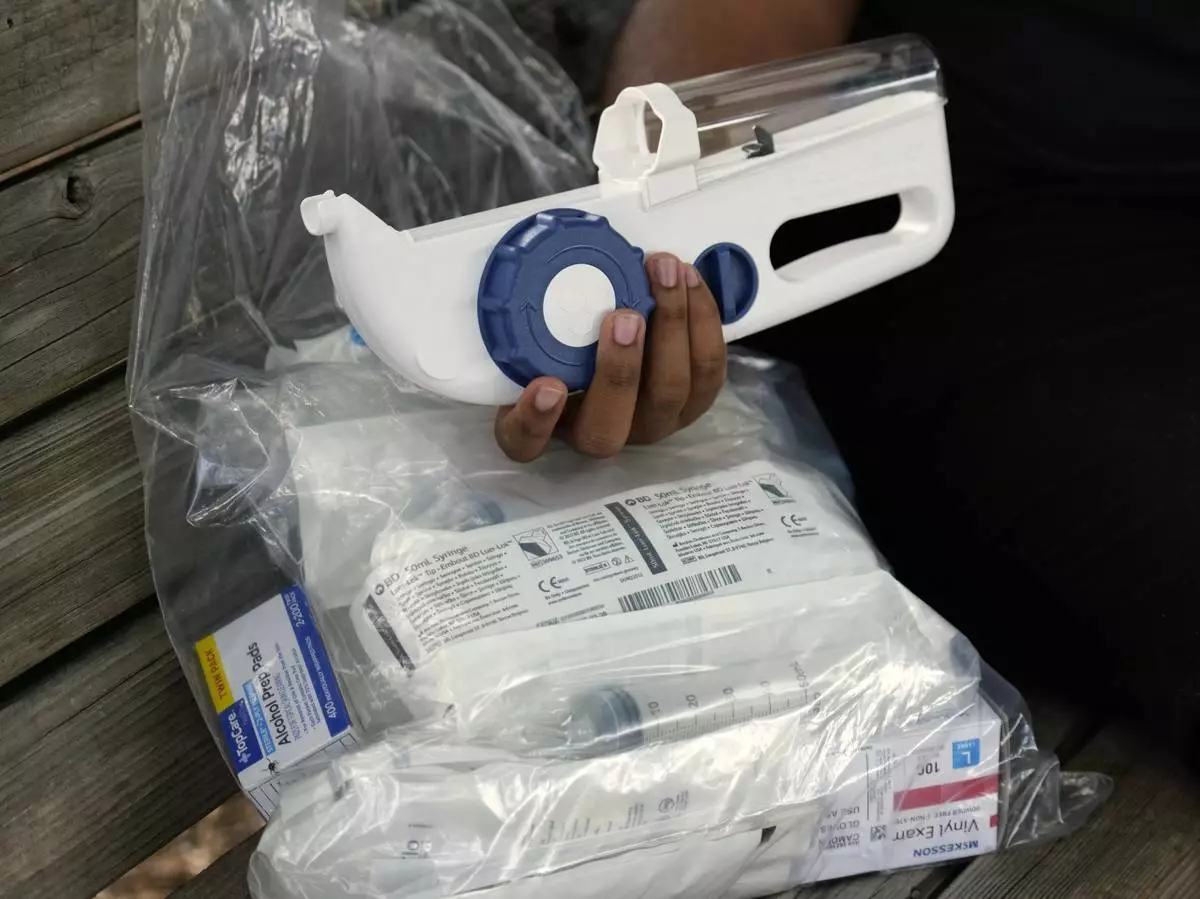

Today, Camden Alderman is a rising senior at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. He takes penicillin daily and gives himself weekly immunoglobulin infusions under his skin, which help fight infection. Still, he’s landed in the hospital a few times in recent years and has developed a kidney problem.

While he doesn’t view gene therapy as a cure-all, he said, “it would just help me kind of lead an easier life.”

That’s proved true for patients who underwent the experimental therapy, such as Dr. Priya Stephen’s 14-year-old son, who participated in a clinical trial in Italy that accepted Americans at the time.

While Stephen is grateful, she said, she can't help feeling guilty that her family got an opportunity others don't: “It’s ethically just not acceptable to have a treatment that we know works, that we know is safe, that people all of a sudden can’t access."

For a while, it seemed gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich was on track for wider availability. Genethon, a French nonprofit research organization, sponsored promising clinical trials but didn’t have funding to continue development, CEO Frédéric Revah said.

Drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline transferred another therapy to Orchard, which announced in 2019 that it had secured a designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration meant to speed up development and review. But Orchard discontinued investment in this and two other rare-disease treatments a couple of years ago, with CEO Dr. Bobby Gaspar saying the company sympathized with affected families and would look for other ways to advance the therapies.

“There’s a huge number of diseases out there that could benefit from gene therapy but for which there is no profitability model because the investment for research is high, the cost of production is high and the number of patients is very low,” Revah said.

Most genetic conditions are rare — each affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. at any given time. Research hasn't made it past early stages for many of them.

Lacey Henderson's daughter, 5-year-old Estella, has alternating hemiplegia of childhood, a neurological condition that affects 300 people in the U.S. Estella is cognitively delayed, has limited use of her hands and becomes temporarily paralyzed in part or all of her body, Henderson said. Medications can curb symptoms, but there’s no cure.

Her Iowa family fundraises through a GoFundMe and a website to develop a gene therapy. They've brought in around $200,000.

“We have three different projects with various researchers," Henderson said. “But the problem is everything is underfunded.”

Financial disincentives plague the process, from drug discovery to development, scientists say.

The amount of work to get from a lab to human testing and through the drug-approval process is “incredibly expensive,” said Dr. Donald Kohn, professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

In the last couple of years, he said, gene-therapy investment has largely dried up.

“If you have to spend $20 million or $30 million to get approval and you have five or 10 patients a year, it’s hard to get a return on investment,” Kohn said. “So we have successful, safe therapies, but it’s more the financial, economic elements that are limiting them from becoming approved drugs.”

Ultimately, most biotechnology companies become public and must focus on shareholder profit, said Francois Vigneault, CEO of the Seattle biotech Shape Therapeutics.

“The board is the thing that gets in the way; they’re trying to maximize gain,” said Vigneault, whose company is privately held. “That’s just greed. That’s just incentive misaligned between corporate company structure and what we should do that’s good for the world.”

Even when treatments make it to market, they might not stay there. The same year Orchard stopped investing in the Wiskott-Aldrich treatment, it also stopped distributing a drug called Strimvelis, approved in Europe to treat the rare disease ADA-SCID, or “bubble boy syndrome.”

Claire Booth, professor of gene therapy and pediatric immunology at University College London, is among those working for change. She co-founded Access to Gene Therapies for Rare Disease, which brings together people across Europe representing academic groups, patient advocates, regulators, funders and drugmakers. They hope to create an independent nonprofit that can support market authorization and access to therapies that aren’t commercially sustainable.

A related effort in the U.S., The Bespoke Gene Therapy Consortium, was organized by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health and includes the FDA, various NIH institutes, and several drug companies and nonprofits. The group’s goals include supporting a handful of clinical trials and exploring ways to streamline regulatory processes.

Some researchers are trying to address the problem scientifically. Dr. Anna Greka said the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has launched an effort to look at commonalities behind various conditions — or nodes, which can be likened to branches meeting at a tree trunk. Fixing the nodes with gene therapies or other treatments, rather than particular “misspellings” in DNA responsible for one disorder, could address multiple diseases simultaneously.

“What this does is it increases the number of patients who can benefit from the therapy,” said Greka, a Broad member. “It also makes it infinitely easier or more attractive to anyone, like a biopharmaceutical company, to take the project forward and try to bring it toward the clinic, because they’re going to have a bigger market.”

Meanwhile, affected families are partnering with each other and scientists to help move the needle. Genethon was created by an association of patients and their relatives to develop treatments for several rare diseases. And a leader of the foundation involved in Opus Genetics has a child with a rare genetic retinal disease.

There’s also new hope for families dealing with Wiskott-Aldrich and bubble boy disease. Last year, the Telethon Foundation in Italy took on responsibility of producing and distributing Strimvelis. This year, the charity announced it was selected for a pilot program of the European Medicines Agency that could help guide its Wiskott-Aldrich gene therapy through the regulatory process there.

Still, scientists say these efforts don’t negate the larger financial quandary surrounding therapies for rare diseases, and it may be a while before such genetic treatments are available to patients worldwide.

“This is a massive challenge, and I’m not entirely sure we’re going to be able to overcome it,” Booth said. “But we have to give it a go because we’ve spent decades and millions making these transformative treatments. And if we don’t try, then it feels like the end of an era.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Robin Alderman, right, looks up to her son, Camden Alderman, 21, who has a rare disease called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, as they pose for a portrait near their home in Greensboro, N.C., Wednesday, June 12, 2024. (AP Photo/Chuck Burton)

Camden Alderman, 21, who has a rare disease called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, holds some of the drugs and medical equipment he uses near his home in Greensboro, N.C., Wednesday, June 12, 2024. (AP Photo/Chuck Burton)

Robin Alderman, right, and her son, Camden Alderman, 21, who has a rare disease called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, pose for a portrait near their home in Greensboro, N.C., Wednesday, June 12, 2024. (AP Photo/Chuck Burton)

Camden Alderman, 21, who has a rare disease called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, holds with an infusion pump he uses near his home in Greensboro, N.C., Wednesday, June 12, 2024. When he was a toddler, doctors removed his spleen because of uncontrolled bleeding. As a young boy, he wound up in the hospital many times and was told he couldn’t play baseball. (AP Photo/Chuck Burton)

Robin Alderman, right, and her son, Camden Alderman, 21, pose for a portrait near their home in Greensboro, N.C., Wednesday, June 12, 2024. Camden, 21, was diagnosed as a baby with a rare disease called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, which is caused by a mutated gene on the X chromosome. It primarily affects boys – up to 10 out of every million — and can cause frequent infections, eczema and excessive bleeding. (AP Photo/Chuck Burton)