RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia’s government palace on Wednesday as President Luis Arce said his country faced an apparent attempted coup.

In a sense, the uprising was the culmination of tensions that have been brewing in Bolivia for months, with protesters streaming into the nation's capital amid a severe economic crisis and as two political titans battle for control of the ruling party.

Click to Gallery

FILE - Bolivia's President Luis Arce, center, attends a ritual in honor of "Pachamama," or Mother Earth, to mark Arce's third year of government, in La Paz, Bolivia, Nov. 8, 2023. Arce had been ex-President Evo Morales' finance minister who oversaw years of strong growth and low inflation, but assuming the presidency in 2020, he encountered a bleak economic reckoning from the coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia’s government palace on Wednesday as President Luis Arce said his country faced an apparent attempted coup.

FILE - Supporters of Bolivian President Luis Arce hold signs that read in Spanish, "Lucho you are not alone" during a march in support of the government, in La Paz, Bolivia, June 17, 2024. Arce and his one-time ally, former President Evo Morales, are battling for the future of Bolivia's splintering Movement for Socialism ahead of elections in 2025. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

FILE - Merchants shout slogans during an anti-government march against the banks' lack of U.S. dollars, in La Paz, Bolivia, June 17, 2024. With prices surging, dollars scarce and lines snaking away from fuel-strapped gas stations, protests in Bolivia have intensified over the economy's precipitous decline. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

FILE - Bolivia's President Luis Arce, center, attends a ritual in honor of "Pachamama," or Mother Earth, to mark Arce's third year of government, in La Paz, Bolivia, Nov. 8, 2023. Arce had been ex-President Evo Morales' finance minister who oversaw years of strong growth and low inflation, but assuming the presidency in 2020, he encountered a bleak economic reckoning from the coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

Military police form a phalanx outside the government palace at Plaza Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia's government palace Wednesday as President Luis Arce said the country faced an attempted coup. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

Army Cmdr. Gen. Juan Jose Zuniga sits inside an armored vehicle at Plaza Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia's government palace Wednesday as President Luis Arce said the country faced an attempted coup. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

Military police block entry to Plaza Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of government palace located in Plaza Murillo, on Wednesday, as President Luis Arce said the country faced an attempted coup. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

At the same time, the attempt to take over the palace appeared to have lacked any meaningful support, and even Arce's rivals quickly closed ranks to defend democracy and repudiate the uprising.

Wednesday's uprising appeared to be led by general commander of the army Juan José Zúñiga, who told journalists gathered at the plaza outside the palace that “Surely soon there will be a new Cabinet of ministers; our country, our state cannot go on like this.” But he added that he recognizes Arce as commander in chief “for now.”

Zúñiga did not explicitly say whether he was the uprising's leader, but in the palace, with bangs echoing behind him, he said the army was trying to “restore democracy and free our political prisoners.”

Arce ordered him to withdraw his soldiers, saying he would not allow the insubordination. Later, he officially removed Zúñiga from his post.

Bolivians have increasingly been suffering the pains of slow growth, surging inflation and scarcity of dollars — a stark change from the prior decade that some called an “economic miracle.”

The country's economy grew by over 4% nearly every year in the 2010s until pitching into the abyss with the coronavirus pandemic. But trouble began earlier, in 2014, when commodity prices plunged and the government dipped into its currency reserves to sustain spending. Then it drew on its gold reserves and even sold dollar bonds locally.

Arce had been finance minister during nearly the entire decade of strong growth, under leftist icon President Evo Morales. Upon assuming the presidency himself in 2020, he encountered a bleak economic reckoning from the pandemic. Diminished gas production sealed the end of Bolivia’s budget-busting economic model.

Today, it’s tapped out. Struggling to import fuel, lines of cars snake away from fuel-strapped gas stations. This year the International Monetary Fund forecasts growth of just 1.6%. Aside from the pandemic plunge in 2020, that would be Bolivia's slowest growth in 25 years.

With this economic despair as a backdrop, president Arce and former leader Morales have clashed in a political fight that has paralyzed the government’s efforts to deal with it. For example, Morales’ allies in Congress have consistently thwarted Arce’s attempts to take on debt to relieve some of the pressure.

By one count, Bolivia has had more than 190 coup attempts and revolutions since its 1825 independence in a repetitive cycle of conflict between political elites in urban areas and disenfranchised by mobilized rural sectors.

This isn't even the first alleged coup attempt in recent years. In 2019, Morales, then Bolivia’s first Indigenous president, ran for an unconstitutional third term. He won a contested vote plagued by allegations of fraud, setting off mass protests that caused 36 deaths and prompted Morales to resign and flee the country.

An interim government from the right-wing opposition took control, led by Jeanine Áñez and Morales’ Movement for Socialism, known by its Spanish acronym MAS, called it a coup.

Arce, Morales's chosen successor, won the election pledging to restore prosperity to Bolivia, once Latin America’s mainstay source of natural gas.

Morales, who still draws considerable support from coca farmers and union workers, was apparently not content to let Arce run for reelection unchallenged. After returning from exile, the charismatic populist last year announced plans to run in the 2025 presidential race, setting off a pitched battle for control of a splintering MAS.

Each man has been seeking to galvanize support for himself — and to undermine his erstwhile ally. That political fight has paralyzed government efforts to deal with the deepening economic despair and analysts have been warning social unrest could be explosive.

“Arce lacks Evo’s charisma, political skills and legacy. But he controls the state apparatus,” Benjamin Gedan, director of the Latin America Program at the Washington-based Wilson Center, said in a text message. “Normally, the upcoming election would serve as a pressure valve. But with Evo’s candidacy up in the air, the opposition divided and the economy in disarray, Bolivia is clearly on edge.”

Despite their differences, both leaders were quick to denounce Wednesday what they called an attempted coup. So, too, did Bolivia's former interim President Áñez, who said on X that Arce and Morales should instead be voted out in 2025.

Leaders from Chile, Paraguay, Brazil, Ecuador and the EU also expressed their support.

“We strongly condemn the unacceptable action of force by a sector of that country’s army,” said Chile’s President Gabriel Boric. "We cannot tolerate any breach of the legitimate constitutional order in Bolivia or anywhere else."

"It’s a dynamic situation and there is a long history of military coups in Bolivia, but a lot of domestic and global power brokers are lining up behind Arce," said Brian Winter, vice president of the New York-based Council of the Americas.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

Bolivian President Luis Arce raises a clenched fist surrounded by supporters and media, outside the government palace in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed the doors of Bolivia's government palace Wednesday in an apparent coup attempt against Arce, but he vowed to stand firm and named a new army commander who ordered troops to stand down. (AP Photo/Rodwy Cazon Barrios)

FILE - Supporters of Bolivian President Luis Arce hold signs that read in Spanish, "Lucho you are not alone" during a march in support of the government, in La Paz, Bolivia, June 17, 2024. Arce and his one-time ally, former President Evo Morales, are battling for the future of Bolivia's splintering Movement for Socialism ahead of elections in 2025. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

FILE - Merchants shout slogans during an anti-government march against the banks' lack of U.S. dollars, in La Paz, Bolivia, June 17, 2024. With prices surging, dollars scarce and lines snaking away from fuel-strapped gas stations, protests in Bolivia have intensified over the economy's precipitous decline. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

FILE - Bolivia's President Luis Arce, center, attends a ritual in honor of "Pachamama," or Mother Earth, to mark Arce's third year of government, in La Paz, Bolivia, Nov. 8, 2023. Arce had been ex-President Evo Morales' finance minister who oversaw years of strong growth and low inflation, but assuming the presidency in 2020, he encountered a bleak economic reckoning from the coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Juan Karita, File)

Military police form a phalanx outside the government palace at Plaza Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia's government palace Wednesday as President Luis Arce said the country faced an attempted coup. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

Army Cmdr. Gen. Juan Jose Zuniga sits inside an armored vehicle at Plaza Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia's government palace Wednesday as President Luis Arce said the country faced an attempted coup. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

Military police block entry to Plaza Murillo in La Paz, Bolivia, Wednesday, June 26, 2024. Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of government palace located in Plaza Murillo, on Wednesday, as President Luis Arce said the country faced an attempted coup. (AP Photo/Juan Karita)

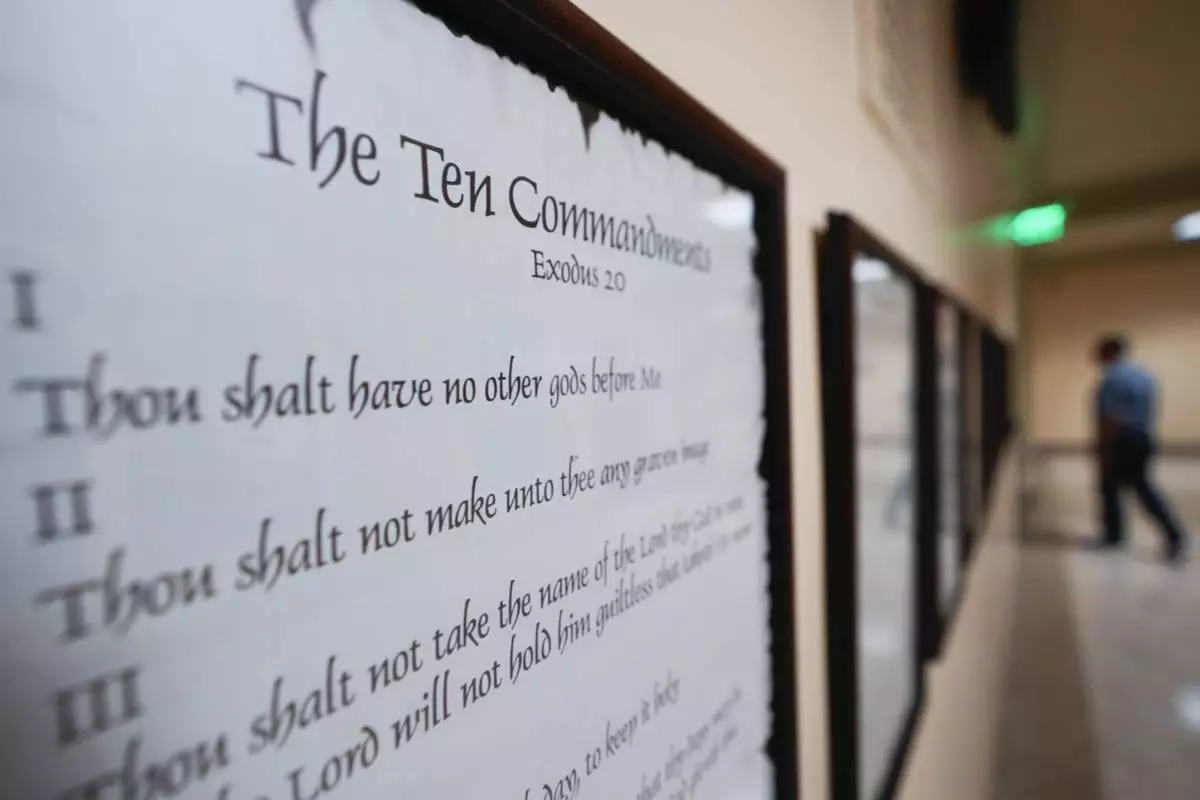

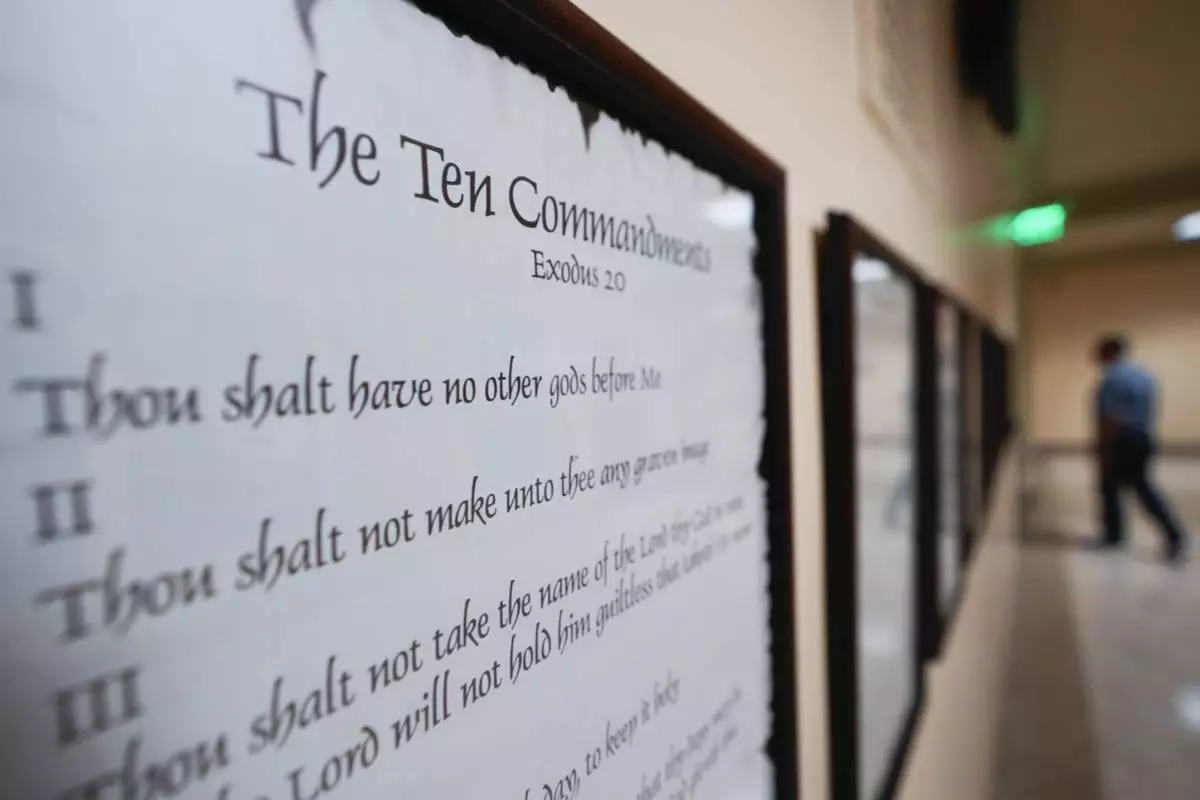

Christians and Jews believe in the Ten Commandments — just not necessarily the version that will hang in every public school and state-funded college classroom in Louisiana.

The required text prescribed in the new law and used on many monuments around the United States is a condensed version of the Scripture passage in Exodus containing the commandments. It has ties to “The Ten Commandments” movie from 1956, and it’s a variation of a version commonly associated with Protestants.

That’s one of the issues related to religious freedom and separation of church and state being raised over this mandate, which was swiftly followed by a lawsuit.

“H.B. 71 is not neutral with respect to religion,” according to the legal complaint filed June 24 by Louisiana clergy, public school parents and civil liberties groups. “It requires a specific, state-approved version of that scripture to be posted, taking sides on theological questions regarding the correct content and meaning of the Decalogue.”

It's also part of a bigger picture. The new law signed by Republican Gov. Jeff Landry on June 19 is not only part of a wave of efforts by GOP-led states to target public schools, it’s also one of the latest conservative Christian victories in the long-standing fight over the role of religion in public life.

Another example came this week in Oklahoma, where the Republican state school superintendent ordered public schools to incorporate the Bible into lessons for grades 5 through 12. In both states, the government leaders argued the historical significance of the religious text was justification enough for use in public schools.

“This cause has persisted because conservative partisans believe it’s a way to mobilize their base,” said Kevin M. Kruse, author of “One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America” and a history professor at Princeton University. He disputes the historical reasoning being used in Louisiana.

“This isn’t about uniting the people of (Landry’s) state; it’s about trying to divide them with a culture war issue that he thinks will win his side votes.”

The Ten Commandments come from Jewish and Christian Scripture, which says there are 10 of them but doesn’t number them specifically. Catholics, Jews and Protestants typically order them differently, and the phrasing can change depending on which Bible translation is used or what part of Scripture they are pulled from.

“If you want to respect the rule of law, you’ve got to start from the original lawgiver, which was Moses” who got the commandments from God, said Landry during the signing ceremony at a Catholic school. The governor also is Catholic.

No Bible translation is named, but the Ten Commandments in the Louisiana law appears to be a variation on the King James Bible version and listed in the order commonly used by Protestants.

Translated in 17th century England from biblical languages, the King James version was for centuries the standard Bible used by evangelicals and other Protestants, even though many today use more modern translations. It is still the go-to translation for some worshippers.

The version in the Louisiana law matches the wording on the Ten Commandments monolith that stands outside of the Texas State Capitol in Austin. It was given to the state in 1961 by the Fraternal Order of Eagles, a more than 125-year-old, Ohio-based service organization with thousands of members. In 2005, a divided U.S. Supreme Court ruled it did not violate the constitution and could stay.

The Eagles did not respond to The Associated Press’s request for comment, but the organization notes on its website that it distributed about 10,000 Ten Commandments plaques in 1954. The organization also partnered with the creators of “The Ten Commandments” to market the film, spreading public displays of the list around the country, according to Kruse, who wrote about the relationship in his book “One Nation Under God.”

“It’s significant that the Louisiana law uses the same text created for 'The Ten Commandments' movie promotions by the Fraternal Order of Eagles and Paramount Pictures because it reminds us that this text isn’t one found in any Bible and isn’t one used by any religious faith,” Kruse said via email. “Instead, it’s a text that was crafted by secular political actors in the 1950s for their own ends.”

Although white evangelical Protestants and many white Catholics unite behind conservative politics today, the King James Bible has been used historically in strategically anti-Catholic ways, including amid the anti-Catholic sentiment in late 19th and early 20th centuries, said Robert Jones. He is president of the Public Religion Research Institute and author of “The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy.”

The Louisiana law contains plenty of evidence, including the specific Bible translation used, that the real intent is to privilege a particular expression of Christianity, Jones said.

“What it is really symbolizing is an evangelical Christian stamp on the space,” he said. “It is less about the ideas and more about its use as a symbol, a totem, that marks territory for a particular religious tradition.”

This version is an odd choice, Kruse said, but he thinks it speaks more to how political leaders view religion.

“Decades ago, we would have seen this as a triumph of Protestantism in a deeply Catholic state, but I think its adoption today just shows how little the political leaders of the state actually care about the substance of religion,” Kruse said.

For Benjamin Marsh, a North Carolina pastor watching the Louisiana law, his primary concern is people's spiritual formation so altering the Ten Commandments is worrisome to him.

“The problem with changing the text of the Ten Commandments is you rob the spiritual implications of the actual biblical text. So you’re giving some vague likeness to the Ten Commandments that isn’t the real thing,” said Marsh. He leads First Alliance Church Winston-Salem, which is part of a conservative evangelical denomination.

Former President Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for president, drew cheers when he invoked the new law on June 22 while speaking to a group of politically influential evangelical Christians in Washington.

“Has anyone read the ‘Thou shalt not steal’? I mean, has anybody read this incredible stuff? It’s just incredible,” Trump said during the Faith & Freedom Coalition gathering. “They don’t want it to go up. It’s a crazy world.’’

The Ten Commandments I AM the LORD thy God. Thou shalt have no other gods before me. Thou shalt not make to thyself any graven images. Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain. Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Honor thy father and thy mother, that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee. Thou shalt not kill. Thou shalt not commit adultery. Thou shalt not steal. Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

FILE - A copy of the Ten Commandments is posted along with other historical documents in a hallway of the Georgia Capitol, Thursday, June 20, 2024, in Atlanta. Christians and Jews believe in the Ten Commandments — just not necessarily the version that will hang in every public school and state-funded college classroom in Louisiana. (AP Photo/John Bazemore, File)