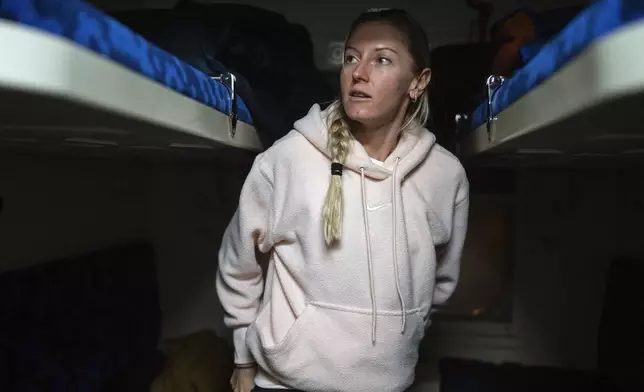

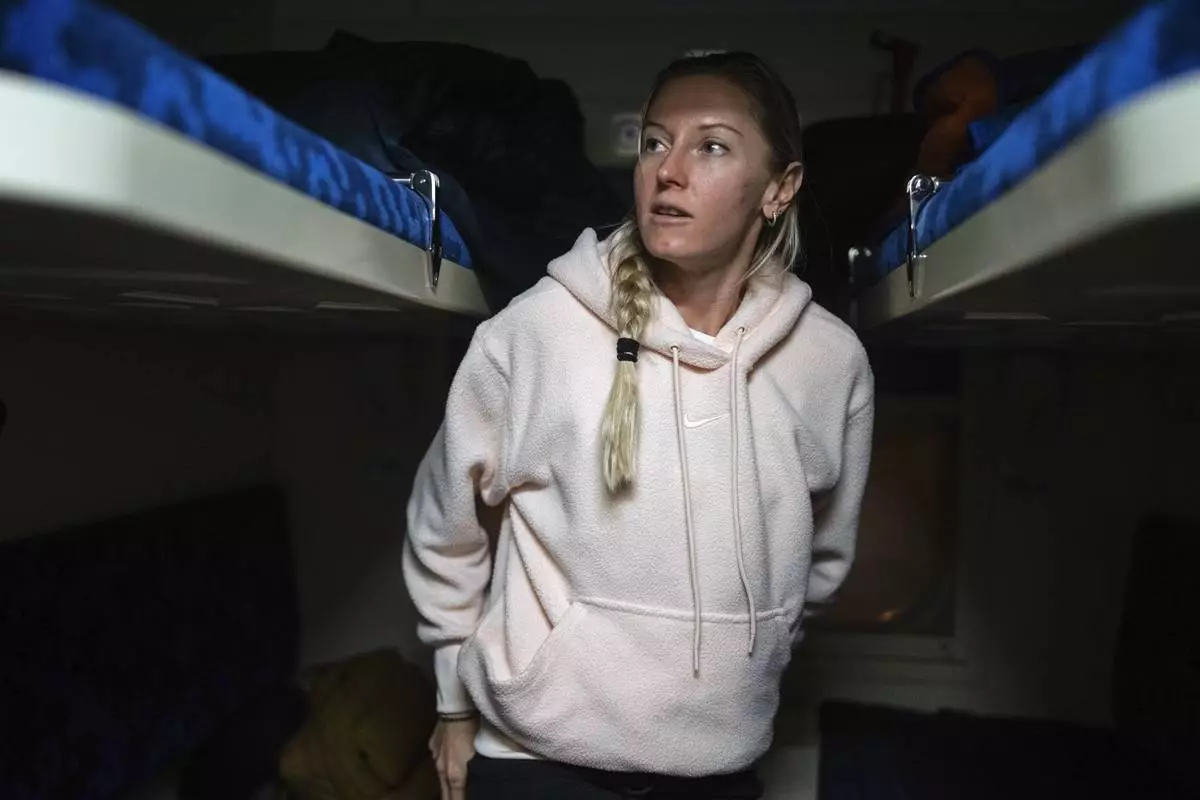

KYIV, Ukraine (AP) — For Ukrainian hurdler Anna Ryzhykova, each stride on the Paris Olympic track will have meaning far beyond the time she clocks.

Her competitions are no longer strictly an individual battle, but war on a different front. Her goal is not just gold, but also to rivet global attention on her country’s fight for survival against Russia.

“You’re not doing it for yourself anymore,” she says. “Winning a medal just for yourself, being a champion, realizing your ambitions — it’s inappropriate.”

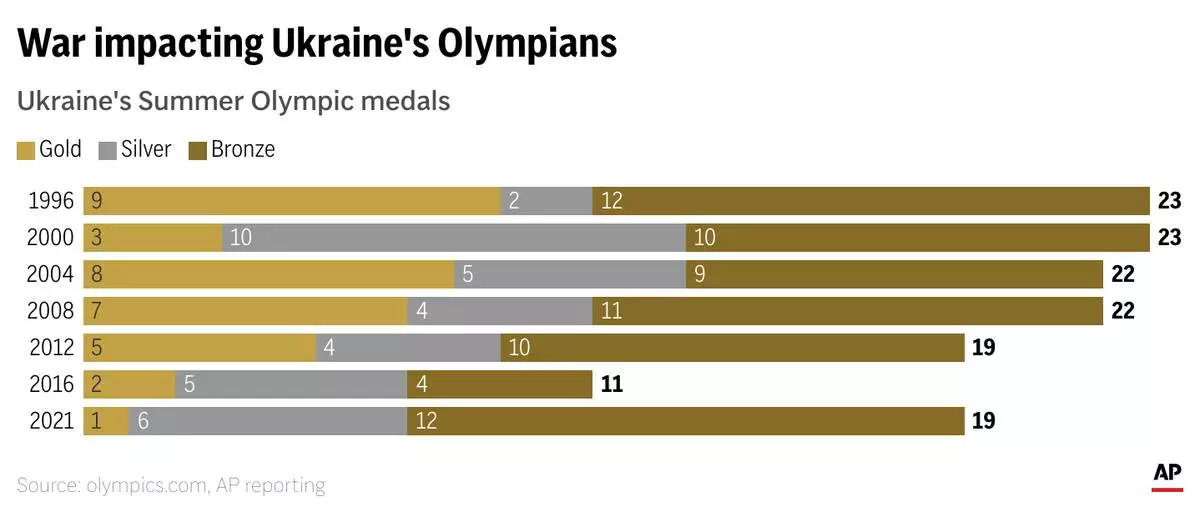

But the broader war is making it increasingly difficult for Ukraine, once a post-Soviet sports power, to get those headline-capturing medals, an Associated Press analysis found.

Skater Oksana Baiul won Ukraine's first Olympic gold, at the 1994 Winter Games, just three years after Ukraine declared independence. The medal ceremony in Lillehammer, Norway, was delayed while organizers hunted for a recording of Ukraine’s anthem, finally securing one from the Ukrainian team.

Pole vault star Sergei Bubka and the boxing Klitschko brothers — Vitali and Wladimir, the Olympic super-heavyweight champion in 1996 — were among other athletes who put the new nation on sport’s map. At the Summer Games, Ukraine outperformed every former Soviet or Eastern bloc state — except Russia and, in 2000, Romania — and through to London in 2012, always finished among the top 13 nations, ranked by total medals won.

Ukrainian performances began dipping after 2014. Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea that year was followed by eight years of armed conflict in eastern Ukraine, where Moscow backed armed separatists before unleashing its even deadlier full-scale invasion in 2022 to subdue the whole country.

Ukraine’s haul of 11 medals at the 2016 Rio Games was its smallest as an independent nation and it tumbled to a low of 22nd in the country rankings. Ukraine recovered to 16th at the pandemic-delayed Olympics in Tokyo in 2021 but just one of its 19 medals was gold — another new low.

Part of the explanation is that fighting takes lives and resources. Just as important is the psychological burden the war imposes on athletes.

While honing their bodies and skills for Paris, they have wrestled with their consciences. Athletes have had to explain to themselves and others why they are still competing when soldiers are dying and lives being ripped apart. Some are emerging from the journey with their priorities reordered and armed with new motivation to fight, through sport, for the broader national cause.

“Our victories are to draw attention to Ukraine,” Ryzhykova says.

She ran on Ukraine’s bronze medal-winning 400-meter relay team in the London Olympics in 2012, and placed 5th in her specialty in Tokyo, the 400-meter hurdles. Any medals she earns this summer will be for her country in a very real sense.

“Attention is drawn to you only when you win, when you perform, when you are on the podium,” she said in an AP interview. “The higher you are, the more attention you attract.”

More than 500 sports facilities have been destroyed since the war began in February 2022. That was the year Russian missiles hit the Lokomotiv sports center in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, depriving Ukrainian artistic swimmers of the training venue they used before winning the team bronze medal in Tokyo. The gleaming “Neptune” aquatic center in Mariupol was bombed in the Russian siege of that devastated port city and now the city is under occupation. That ruined the plans of diver Stanislav Oliferchyk to use it as his Olympic training base for Paris.

High jumper Oleh Doroshchuk, aged 23 and one of Ukraine’s brightest prospects in Olympic track and field in Paris, has learned to ignore aid raid sirens that blare over his hometown, Kropyvnytskyi in central Ukraine, so they don’t interrupt his training. Still, after particularly deadly Russian attacks that regularly hit the country, Doroschuk says he’s been forced to look inside himself, questioning whether it’s morally right that he’s “just training” when other men are defending front lines.

“I think everyone has these kinds of thoughts,” he said. “Many people among those whom I know are fighting, and some were killed.”

Across Ukraine, air raids often derail training.

“You sit in the bomb shelter for an hour, then come out for 15 minutes and start warming up and moving again. The alarm goes off again, and you go back to the bomb shelter,” Ryzhykova says. She mostly trains abroad as a result.

Among Ukraine’s many tens of thousands of dead and injured are athletes, coaches and others in sports organizations who together helped Ukraine to stand on its own as a sporting nation after it broke free of the former Soviet sports machine.

Some of the athletes killed might have had a shot of qualifying for Paris. Some of the coaches had been nurturing future generations.

Ryzhykova lost a mentor who helped ignite her passion for sports. Coach Valentyn Vozniuk and his wife, Iryna Tymoshenko, were among 46 people killed by a supersonic missile that slammed into an apartment building in Dnipro in 2023.

Vozniuk, who was 75, led the Dnipro sports school where Ryzhykova started track and field and where she still trains on trips home.

“He was always very cheerful, a happy person who did everything to make children come, enjoy, and stay,” she recalls.

She worries the war will accelerate a downward spiral for Ukrainian sport. “Few children are coming for training now, many have left,” she notes.

“There are times when depression and a feeling of not wanting to do anything set in,” she says. “And when you’re at a training camp and read the news about a massive rocket attack, you worry about all your relatives and loved ones.”

In Paris, Ukrainian athletes will endure another ordeal: the likelihood of crossing paths with competitors from Russia and ally Belarus.

The International Olympic Committee barred the two nations from team sports in Paris but didn’t bend to Ukrainian pleas for their complete exclusion.

Instead, Russians and Belarusians who pass a two-step vetting procedure will compete individually as neutrals. They must not have publicly supported the invasion or be affiliated with military or state security agencies.

The IOC has said dozens of Russian and Belarusian athletes qualify.

Ryzhykova struggles with the prospect of face-to-face encounters.

“I can’t even imagine this anger,” she says. “How to restrain oneself, how to look at them.”

Her priority remains Ukraine and keeping its losses and sacrifices in the spotlight.

“We cannot be without a position, be on the sidelines — because we are opinion leaders. And we have to be a support for our people,” Ryzhykova says.

“It will be challenging at this Olympics because there is no room for defeat or injury,” she adds. “It’s tough to cope with, but it’s both motivation and responsibility.”

__

Leicester reported from Paris.

__

AP Olympics coverage: https://apnews.com/hub/2024-paris-olympic-games

Graphic shows medals won by Ukraine during the Summer Olympics dating back to 1996

High jumper Oleh Doroshchuk holds a gold medal he won during a competition in Bakhmut, Ukraine, during an interview in his house, in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, Friday, April 19, 2024. Russia occupied Bakhmut in spring of 2023 after the city was reduced to rubble in months-long grinding battle. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

High jumper Oleh Doroshchuk works out during a training session at Zirka stadium, in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, Friday, April 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

High jumper Oleh Doroshchuk trains at Zirka stadium, in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, Friday, April 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

High jumper Oleh Doroshchuk lifts weights during a training session at a regional youth sport school for the Olympics, in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, Thursday, April 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

Coach Hennadii Zditovetskyi, left, watches high jumper Oleh Doroshchuk during a training session at a regional youth sport school for the Olympics, in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, Thursday, April 18, 2024. Doroshchuk, one of Ukraine’s brightest prospects in Olympic track and field in Paris, has learned to ignore aid raid sirens that blare over his hometown in central Ukraine, so they don’t interrupt his training. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

High jumper Oleh Doroshchuk changes his clothes in a dressing room with a sign that reads in Ukrainian, "Shelter," prior a training session at regional youth sport school for the Olympics, in Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, Thursday, April 18, 2024. Doroshchuk says he’s been forced to look inside himself, questioning whether it’s morally right that he’s “just training” when other men are defending front lines. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco)

FILE - Gold medalist, Zhan Beleniuk of Ukraine, celebrates on the podium during the medal ceremony for the men's 87kg Greco-Roman wrestling at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Wednesday, Aug. 4, 2021, in Chiba, Japan. An Associated Press analysis found Russia's war is making it increasingly difficult for Ukraine, once a post-Soviet sports power, to get those headline-capturing medals. Ukrainian performances began dipping after 2014, the year of Russia's illegal annexation of Crimea. (AP Photo/Aaron Favila, File)

Hurdler Anna Ryzhykova trains at the sports center in Kyiv, Ukraine on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Hurdler Anna Ryzhykova looks for her seat in a train before her departure for Poland at the train station in Kyiv, Ukraine on Tuesday, Jan. 9, 2024. “It will be challenging at this Olympics because there is no room for defeat or injury,” she says. “It’s tough to cope with, but it’s both motivation and responsibility.” (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Hurdler Anna Ryzhykova walks on a platform before departing for Poland at the train station in Kyiv, Ukraine on Tuesday, Jan. 9, 2024. “Our victories are to draw attention to Ukraine,” Ryzhykova says. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Hurdler Anna Ryzhykova trains at the sports center in Kyiv, Ukraine on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024. Ryzhykova lost a mentor who helped ignite her passion for sports. Coach Valentyn Vozniuk and his wife, Iryna Tymoshenko, were among 46 people killed by a supersonic missile that slammed into an apartment building in Dnipro in 2023. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)

Hurdler Anna Ryzhykova trains at the sports center in Kyiv, Ukraine on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024. Her competitions are no longer strictly an individual battle, but war on a different front. Her goal is not just gold, but also to rivet global attention on her country’s fight for survival against Russia. “You’re not doing it for yourself anymore,” she says. “Winning a medal just for yourself, being a champion, realizing your ambitions — it’s inappropriate.” (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka)