MEXICO CITY (AP) — Frida Kahlo had no religious affiliation. Why, then, did the Mexican artist depict several religious symbols in the paintings she produced until her death on July 13, 1954?

“Frida conveyed the power of each individual,” said art researcher and curator Ximena Jordán. “Her self-portraits are a reminder of the ways in which we can exercise the power that life — or God, so to speak — has given us.”

Click to Gallery

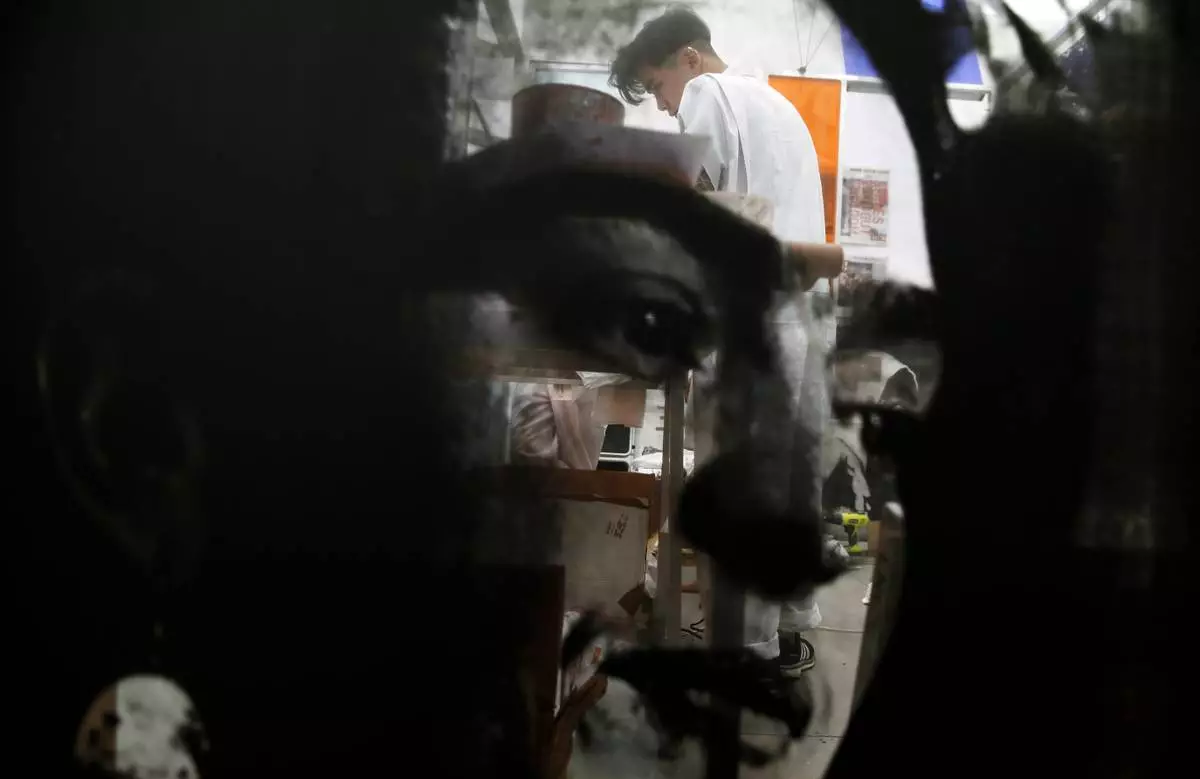

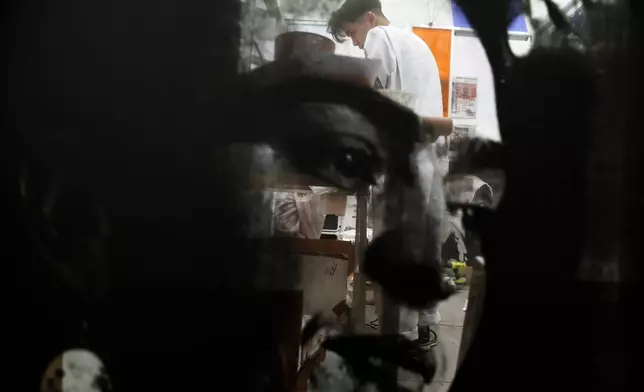

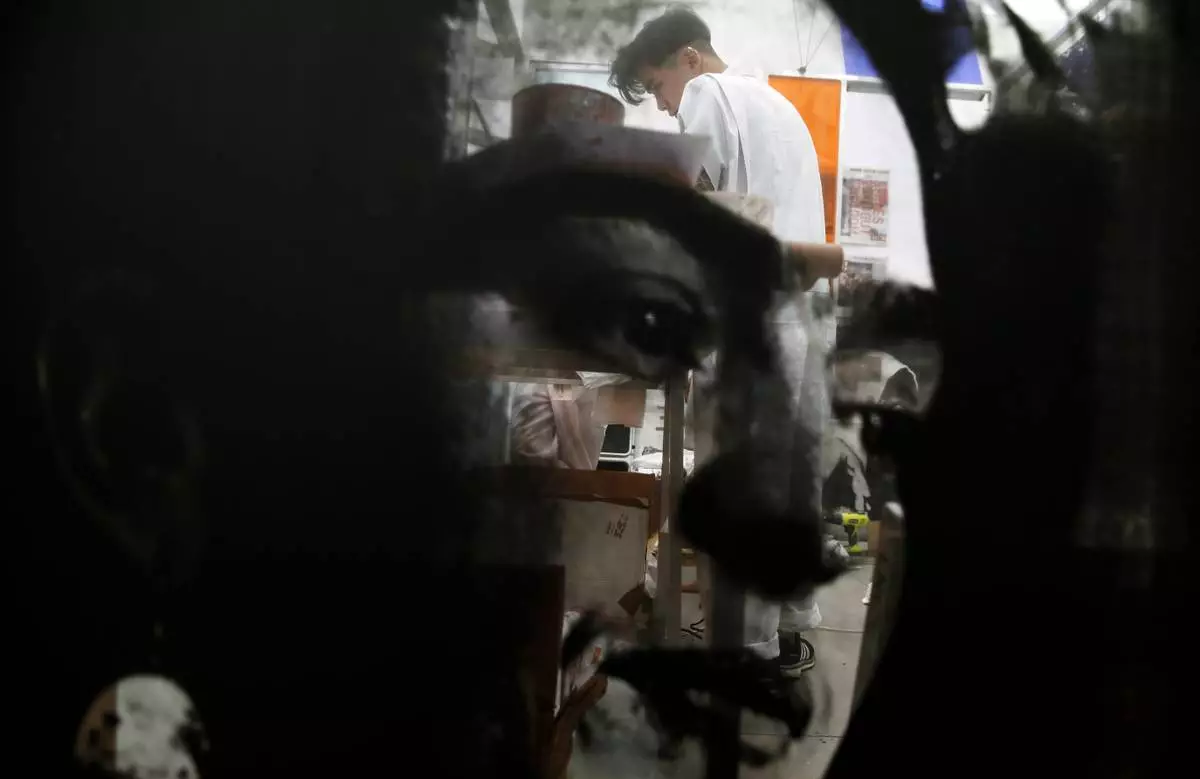

FILE - An artist makes screen prints in the background of Frida Kahlo's face printed on the art installation from artists, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Tomas Vu, at the Untitled Art gallery during Art Basel, Dec. 6, 2018, in Miami Beach, Florida. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, File)

FILE - A mural of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, painted by Los Angeles muralist Levi Ponce, decorates the Pacoima section of Los Angeles, known as Mural Mile, June 6, 2015. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel, File)

FILE - Play director and actress Carla Liguori performs the role of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo in the musical "Frida, entre lo absurdo y lo fugaz" or "Frida, between the Absurd and Fleeting" in Buenos Aires, Argentina, July 15, 2013. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko, File)

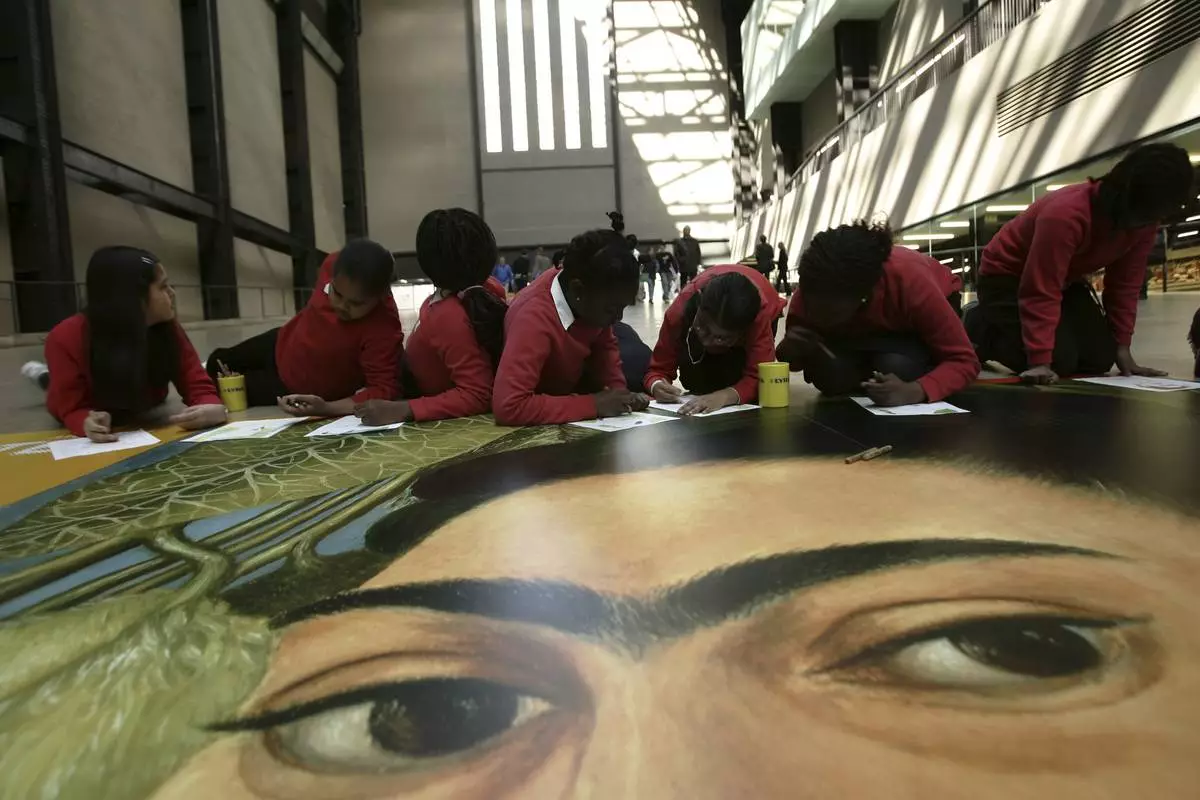

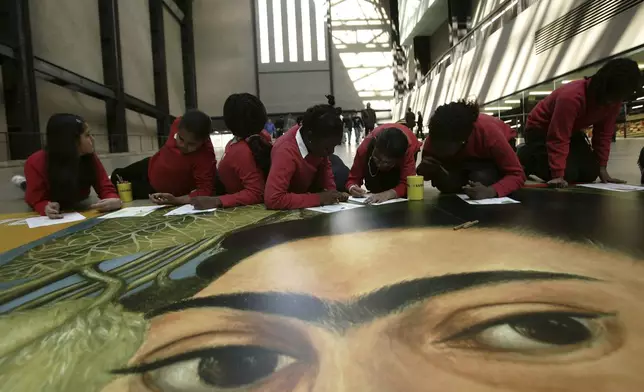

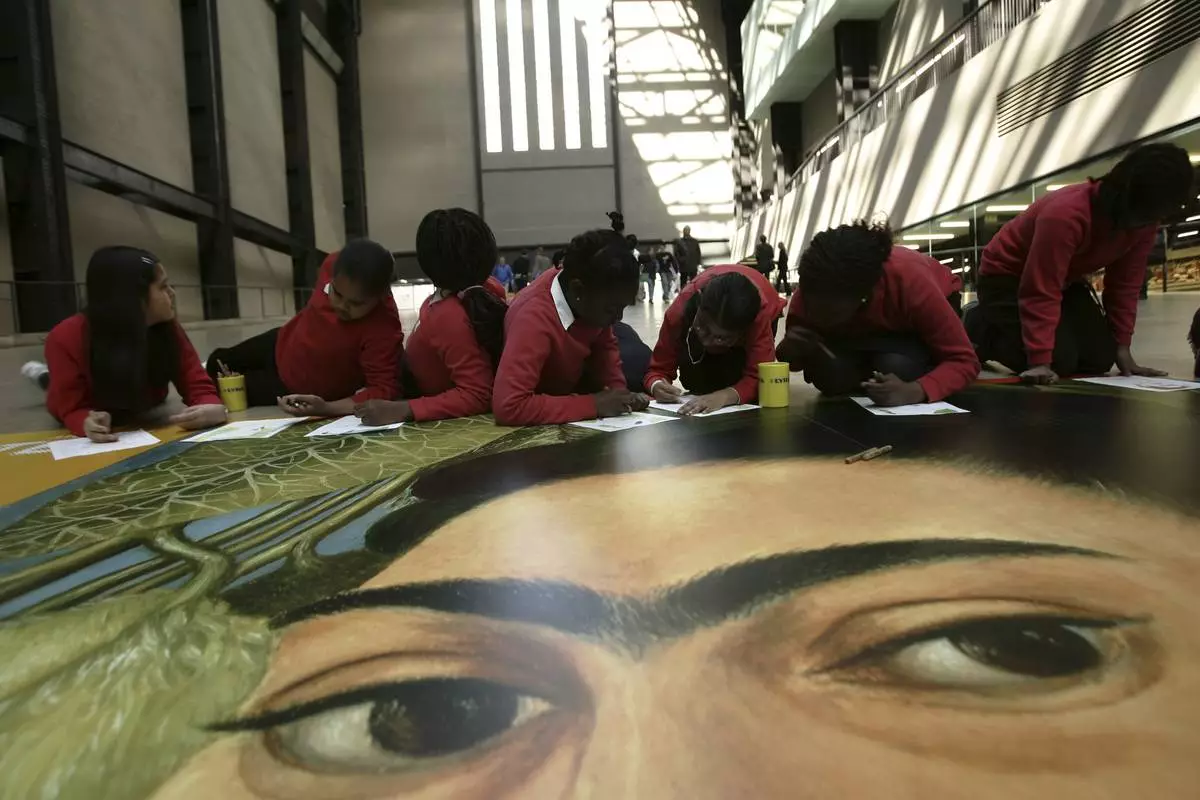

FILE - Children color in a giant poster of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, during a ceremony marking the 5th anniversary of the Tate Modern gallery in Southwark, London, May 12, 2005. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis, File)

FILE - Dione Lugones shows off her tattoo in the likeness of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, at La Marca, or The Brand tattoo parlor in Havana, Cuba, Feb. 3, 2016. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Desmond Boylan, File)

FILE - Autumn Williams and Mateo Londono view a 1938 photo by Nickolas Muray titled "Frida and Diego with Gas Mask" at the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera art show hosted by the NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, March 10, 2015. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/J Pat Carter, File)

FILE - A visitor stylized as Frida Kahlo takes a selfie with Frida's Kahlo self-portrait at the Frida Kahlo retrospective exhibition at the Faberge Museum in St. Petersburg, the first Frida Kahlo exposition of such scale in Russia, Feb. 2, 2016. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Dmitry Lovetsky, File)

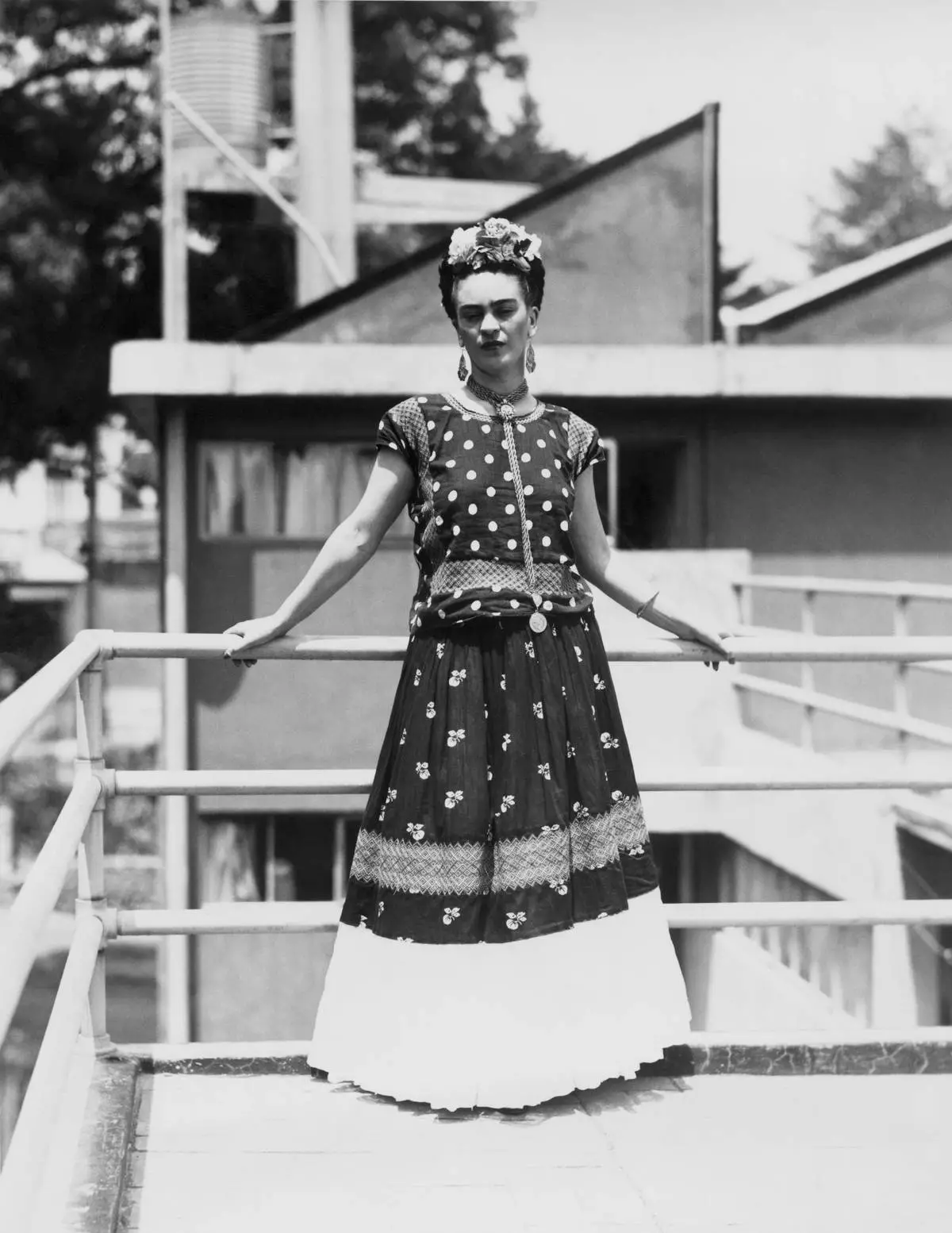

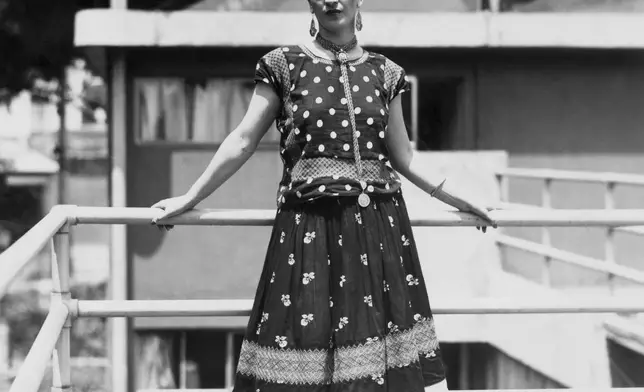

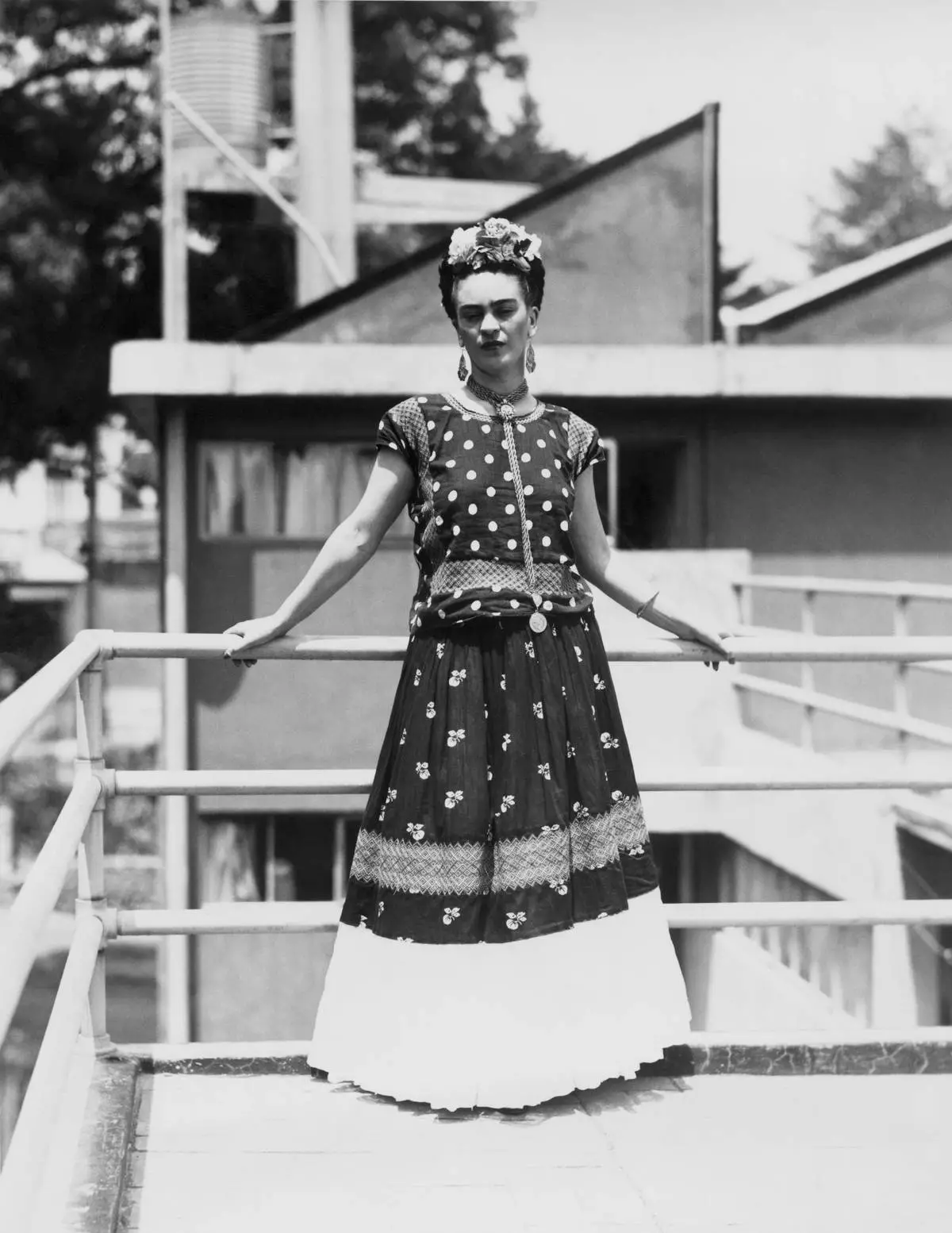

FILE - Frida Kahlo, Mexican painter and surrealist, poses at her home in Mexico City, April 14, 1939. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - The house where Frida Kahlo once lived, called the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo House and Studio Museum, is linked with a walkway bridge to a white and pink house-studio once occupied by her husband Diego Rivera, in Mexico City, Oct. 31, 2017. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Anita Snow, File)

FILE - An art handler adjusts Frida Kahlo's “Diego and I” on display at Sotheby's auction house during a press preview for the Modern Evening auction, Nov. 5, 2021, in New York. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File)

Born in 1907 in Mexico City — where her “Blue House” remains open for visitors — Kahlo used her own personal experiences as a source of inspiration for her art.

The bus accident that she survived in 1925, the physical pain that she endured as a consequence and the tormented relationship with her husband — Mexican muralist Diego Rivera — all nurtured her creativity.

Her take on life and spirituality sparked a connection between her paintings and her viewers, many of whom remain passionate admirers of her work on the 70th anniversary of her death.

One of the keys to understand how she achieved this, Jordán said, lies in her self-portraits.

Kahlo appears in many of her paintings, but she did not portray herself in a naturalistic way. Instead, Jordán said, she “re-created” herself through symbols that convey the profoundness of interior human life.

“Diego and I” is the perfect example. Painted by Kahlo in 1949, it sold for $34.9 million at Sotheby’s in New York in 2021, an auction record for a work by a Latin American artist.

In the painting, Kahlo’s expression is serene despite the tears falling from her eyes. Rivera’s face is on her forehead. And, in the center of his head, a third eye, which signifies the unconscious mind in Hinduism and enlightenment in Buddhism.

According to some interpretations, the painting represents the pain that Rivera inflicted on her. Jordán, though, offers another reading.

“The religiosity of the painting is not in the fact that Frida carries Diego in her thoughts,” Jordán said. “The fact that she bears him as a third eye, and Diego has a third eye of his own, reflects that his affection for her made her transcend to another dimension of existence.”

In other words, Kahlo portrayed how individuals connect to their spirituality through love.

“I connected with her heart and writings,” said Cris Melo, a 58-year-old American artist whose favorite Kahlo work is the aforementioned painting. “We had the same love language, and similar history of heartache.”

Melo, unlike Kahlo, did not go through a bus accident that punctured her pelvis and led to a life of surgeries, abortions and a leg amputation.

Still, Melo said, she experienced years of physical pain. And in the midst of that suffering, while fearing that resilience might slip away, she said to herself: “If Frida could handle this, so can I.”

Even if most of her artwork depicts her emotional and physical suffering, Kahlo’s paintings do not provoke sadness or helplessness. On the contrary, she is seen as a woman — not only an artist — strong enough to deal with a broken body that never weakened her spirit.

“Frida inspires many people to be consistent,” said Amni, a London-based Spanish artist who asked to be identified only by his artistic name and reinterprets Kahlo’s works with artificial intelligence.

“Other artists have inspired me, but Frida has been the most special because of everything she endured,” Amni said. “Despite her suffering, the heartbreak, the accident, she was always firm.”

For him, as for Melo, Kahlo’s most memorable works are those in which Rivera appears on her forehead, like a third eye.

According to Jordán, Kahlo touched a chord that most artists of her time did not. Influenced by revolutionary nationalism, muralists like Rivera or David Alfaro Siqueiros kept a distance from their viewers though intellectual works that mainly focused on their social, historic and political views.

Kahlo, on the other hand, was not shy in portraying her physical disabilities, her bisexuality and the diversity of beliefs that weigh on the human spirit.

In “The Wounded Deer,” for example, she is transformed into an animal whose body bleeds after being shot by arrows. And just like a martyr in Catholic imagery, Kahlo’s expression remains composed.

Aligned with a Marxist ideology, Kahlo thought that the Catholic Church was emasculating, meddlesome and racist. But in spite of her disdain toward the institution, she understood that devotion leads to a beneficial spiritual path.

A decade after her accident, probably overwhelmed by the fact that she survived, Kahlo started collecting votive offerings — tiny paintings that Catholics offer as gratitude for miracles. In her Blue House, the 473 votive offerings are still preserved.

Kahlo might have regarded her survival as a miracle, Jordán said. “The only difference is that she, due to her context, did not attribute that miracle to a deity of Catholic origin, but to the generosity of life.”

Perhaps that’s why, in her final days, she decided to paint a series of vibrant, colorful watermelons that would be her last work.

In that canvas, over a split watermelon lying underneath a clouded sky, she wrote: “Vida la vida,” or “Long live life.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

FILE - An artist makes screen prints in the background of Frida Kahlo's face printed on the art installation from artists, Rirkrit Tiravanija and Tomas Vu, at the Untitled Art gallery during Art Basel, Dec. 6, 2018, in Miami Beach, Florida. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, File)

FILE - A mural of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, painted by Los Angeles muralist Levi Ponce, decorates the Pacoima section of Los Angeles, known as Mural Mile, June 6, 2015. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel, File)

FILE - Play director and actress Carla Liguori performs the role of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo in the musical "Frida, entre lo absurdo y lo fugaz" or "Frida, between the Absurd and Fleeting" in Buenos Aires, Argentina, July 15, 2013. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko, File)

FILE - Children color in a giant poster of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, during a ceremony marking the 5th anniversary of the Tate Modern gallery in Southwark, London, May 12, 2005. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis, File)

FILE - Dione Lugones shows off her tattoo in the likeness of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, at La Marca, or The Brand tattoo parlor in Havana, Cuba, Feb. 3, 2016. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Desmond Boylan, File)

FILE - Autumn Williams and Mateo Londono view a 1938 photo by Nickolas Muray titled "Frida and Diego with Gas Mask" at the Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera art show hosted by the NSU Art Museum in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, March 10, 2015. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/J Pat Carter, File)

FILE - A visitor stylized as Frida Kahlo takes a selfie with Frida's Kahlo self-portrait at the Frida Kahlo retrospective exhibition at the Faberge Museum in St. Petersburg, the first Frida Kahlo exposition of such scale in Russia, Feb. 2, 2016. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Dmitry Lovetsky, File)

FILE - Frida Kahlo, Mexican painter and surrealist, poses at her home in Mexico City, April 14, 1939. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - The house where Frida Kahlo once lived, called the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo House and Studio Museum, is linked with a walkway bridge to a white and pink house-studio once occupied by her husband Diego Rivera, in Mexico City, Oct. 31, 2017. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Anita Snow, File)

FILE - An art handler adjusts Frida Kahlo's “Diego and I” on display at Sotheby's auction house during a press preview for the Modern Evening auction, Nov. 5, 2021, in New York. The 70th anniversary of Kahlo’s death is on July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File)

What's in a name change, after all?

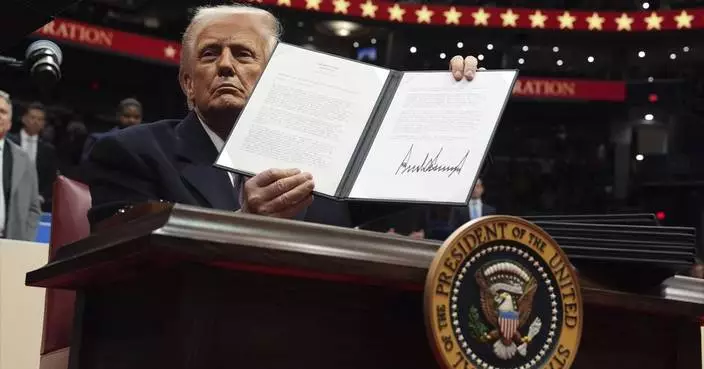

The water bordered by the Southern United States, Mexico and Cuba will be critical to shipping lanes and vacationers whether it’s called the Gulf of Mexico, as it has been for four centuries, or the Gulf of America, as President Donald Trump ordered this week. North America’s highest mountain peak will still loom above Alaska whether it’s called Mt. Denali, as ordered by former President Barack Obama in 2015, or changed back to Mt. McKinley as Trump also decreed.

But Trump's territorial assertions, in line with his “America First” worldview, sparked a round of rethinking by mapmakers and teachers, snark on social media and sarcasm by at least one other world leader. And though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis put the Trumpian “Gulf of America” on an official document and some other gulf-adjacent states were considering doing the same, it was not clear how many others would follow Trump's lead.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum joked that if Trump went ahead with the renaming, her country would rename North America “Mexican America.” On Tuesday, she toned it down: “For us and for the entire world it will continue to be called the Gulf of Mexico.”

Map lines are inherently political. After all, they're representations of the places that are important to human beings — and those priorities can be delicate and contentious, even more so in a globalized world.

There’s no agreed-upon scheme to name boundaries and features across the Earth.

“Denali” is the mountain's preferred name for Alaska Natives, while “McKinley" is a tribute to President William McKinley, designated in the late 19th century by a gold prospector. China sees Taiwan as its own territory, and the countries surrounding what the United States calls the South China Sea have multiple names for the same body of water.

The Persian Gulf has been widely known by that name since the 16th century, although usage of “Gulf” and “Arabian Gulf” is dominant in many countries in the Middle East. The government of Iran — formerly Persia — threatened to sue Google in 2012 over the company’s decision not to label the body of water at all on its maps. Many Arab countries don’t recognize Israel and instead call it Palestine. And in many official releases, Israel calls the occupied West Bank by its biblical name, “Judea and Samaria.”

Americans and Mexicans diverge on what to call another key body of water, the river that forms the border between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. Americans call it the Rio Grande; Mexicans call it the Rio Bravo.

Trump's executive order — titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness” — concludes thusly: “It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes. The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our Nation’s rich past.”

But what to call the gulf with the 3,700-mile coastline?

“It is, I suppose, an internationally recognized sea, but (to be honest), a situation like this has never come up before so I need to confirm the appropriate convention,” said Peter Bellerby, who said he was talking over the issue with the cartographers at his London company, Bellerby & Co. Globemakers. “If, for instance, he wanted to change the Atlantic Ocean to the American Ocean, we would probably just ignore it."

As of Wednesday night, map applications for Google and Apple still called the mountain and the gulf by their old names. Spokespersons for those platforms did not immediately respond to emailed questions.

A spokesperson for National Geographic, one of the most prominent map makers in the U.S., said this week that the company does not comment on individual cases and referred questions to a statement on its web site, which reads in part that it "strives to be apolitical, to consult multiple authoritative sources, and to make independent decisions based on extensive research.” National Geographic also has a policy of including explanatory notes for place names in dispute, citing as an example a body of water between Japan and the Korean peninsula, referred to as the Sea of Japan by the Japanese and the East Sea by Koreans.

In discussion on social media, one thread noted that the Sears Tower in Chicago was renamed the Willis Tower in 2009, though it's still commonly known by its original moniker. Pennsylvania's capital, Harrisburg, renamed its Market Street to Martin Luther King Boulevard and then switched back to Market Street several years later — with loud complaints both times. In 2017, New York's Tappan Zee Bridge was renamed for the late Gov. Mario Cuomo to great controversy. The new name appears on maps, but “no one calls it that,” noted another user.

“Are we going to start teaching this as the name of the body of water?” asked one Reddit poster on Tuesday.

“I guess you can tell students that SOME PEOPLE want to rename this body of water the Gulf of America, but everyone else in the world calls it the Gulf of Mexico,” came one answer. “Cover all your bases — they know the reality-based name, but also the wannabe name as well.”

Wrote another user: “I'll call it the Gulf of America when I'm forced to call the Tappan Zee the Mario Cuomo Bridge, which is to say never.”

FILE - President Donald Trump speaks in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Peter Bellerby, the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, holds a globe at a studio in London, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - A boat is seen on the Susitna River near Talkeetna, Alaska, on Sunday, June 13, 2021, with Denali in the background. Denali, the tallest mountain on the North American continent, is located about 60 miles northwest of Talkeetna. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen, File)

FILE - The water in the Gulf of Mexico appears bluer than usual off of East Beach, Saturday, June 24, 2023, in Galveston, Texas. (Jill Karnicki/Houston Chronicle via AP, File)