BENGALURU, India (AP) — At a Coca-Cola factory on the outskirts of Chennai in southern India a giant battery powers machinery day and night, replacing a diesel-spewing generator. It's one of just a handful of sites in India powered by electricity stored in batteries, a key component to fast-tracking India’s energy transition away from dirty fuels.

The country's lithium ion battery storage industry — which can store electricity generated by wind turbines or solar panels for when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing — makes up just 0.1% of global battery storage systems. But battery storage is growing fast, with around a third of India's total battery infrastructure coming online just this year.

Click to Gallery

BENGALURU, India (AP) — At a Coca-Cola factory on the outskirts of Chennai in southern India a giant battery powers machinery day and night, replacing a diesel-spewing generator. It's one of just a handful of sites in India powered by electricity stored in batteries, a key component to fast-tracking India’s energy transition away from dirty fuels.

Electrician A. Prakash checks the parameter of the output breaker of a 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur district, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

Security staff stand in front of the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur district, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

Team leader K. Sridhar, center, closes the doors after a routine check of lithium ion batteries for a 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur District, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

A worker walks in front of the 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur district, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

“Our orders are growing exponentially,” said Ayush Misra, CEO of Amperehour Energy, the company that installed the batteries at the Chennai factory. “It’s a really exciting time to be a battery storage provider."

India currently has around 100 megawatts of storage capacity from batteries, with another 3.3 gigawatts of clean energy storage coming from hydropower. The Indian government estimates that the country will need about 74 gigawatts of energy storage from batteries, hydropower and nuclear energy by 2032, but experts think the country actually needs closer to double that amount to meet the country's energy needs.

Some customers are still wary of using battery technology for storage, and the storage systems can be seen as more expensive than the more commonly used coal. The supply chain of batteries is also concentrated in China, meaning the sector is vulnerable to geopolitical volatility.

But markets don’t think customers will be hesitant about batteries for long, with major Indian businesses announcing significant investments in the industry.

In January this year, energy giant Reliance Industries said it will build a 5,000-acre factory in Jamnagar, Gujarat. And in March, Goodenough Energy said it will spend $53 million by 2027 to set up a 20 million kilowatt-hour battery factory in the northern region of Jammu and Kashmir.

Alexander Hogeveen Rutter, an independent energy analyst based in Bengaluru, said upping storage capacity should be done alongside ramping up renewables.

“Clean energy combined with adequate storage can be an alternative to coal. Not in the future but right now,” he said. He added that it’s a “myth” that clean energy is more expensive than coal, as current prices of renewable energy combined with storage is cheaper than new coal.

Global battery costs are declining faster than expected, and experts say that if costs continue to plummet, energy storage systems can better compete with both coal and clean energy sources like hydropower and nuclear energy that can also control their supply to meet demand.

“Battery storage is now the largest resource to meet California’s evening peak electricity requirements. It’s more than gas, nuclear or coal,” he said. This is being replicated in the U.K., China and even smaller nations like Tonga. “There’s no reason why this can’t happen in India too," he said.

One of India's unique challenges is that energy needs are growing more rapidly than most nations: the population is increasing and extreme heat fueled by climate change means more and more people are using energy-guzzling air conditioning. India’s electricity demand grew by 7% last year and is expected to grow by at least 6% every year for the next three years, according to the International Energy Agency.

“The country needs to quadruple its renewable energy deployment just to meet demand growth,” said Hogeveen Rutter.

Ankit Mittal, co-founder of Sheru, a software company that offers energy storage and management solutions, said that making battery storage sites more flexible can help the industry ramp up quickly.

Mittal said battery storage sites should be more accessible to the national energy grid, so they can provide electricity to whichever regions need the extra boost of energy most. Currently, battery storage sites in India only power up more local sites.

To encourage further growth of the battery sector, the Indian government announced last year a $452 million scheme to support an additional four gigawatts of battery storage by 2031. But the government also provides subsidies for coal plants, making the electricity generated there a cheaper bet for some utility companies.

Future government policy could level the playing field. The country is set to announce a new national budget later in July that industry leaders hope will contain incentives for clean energy storage.

Akshay Singhal, co-founder of the Bengaluru-based battery tech startup Log 9 Materials, thinks that better government support can help the country meet growing energy demands “the right way,” with clean energy.

“One significant policy change can kickstart the entire ecosystem,” he said.

Journalist Mahesh Kumar contributed to this report from Chennai, India.

Follow Sibi Arasu on X at @sibi123

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Team leader K. Sridhar, center, closes the doors after a routine check of lithium ion batteries of 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur District, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

Electrician A. Prakash checks the parameter of the output breaker of a 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur district, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

Security staff stand in front of the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur district, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

Team leader K. Sridhar, center, closes the doors after a routine check of lithium ion batteries for a 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur District, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

A worker walks in front of the 500-kilowatt battery energy storage system inside the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages factory in Thiruvallur district, on the outskirts of Chennai, India, Tuesday, July 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahesh Kumar A.)

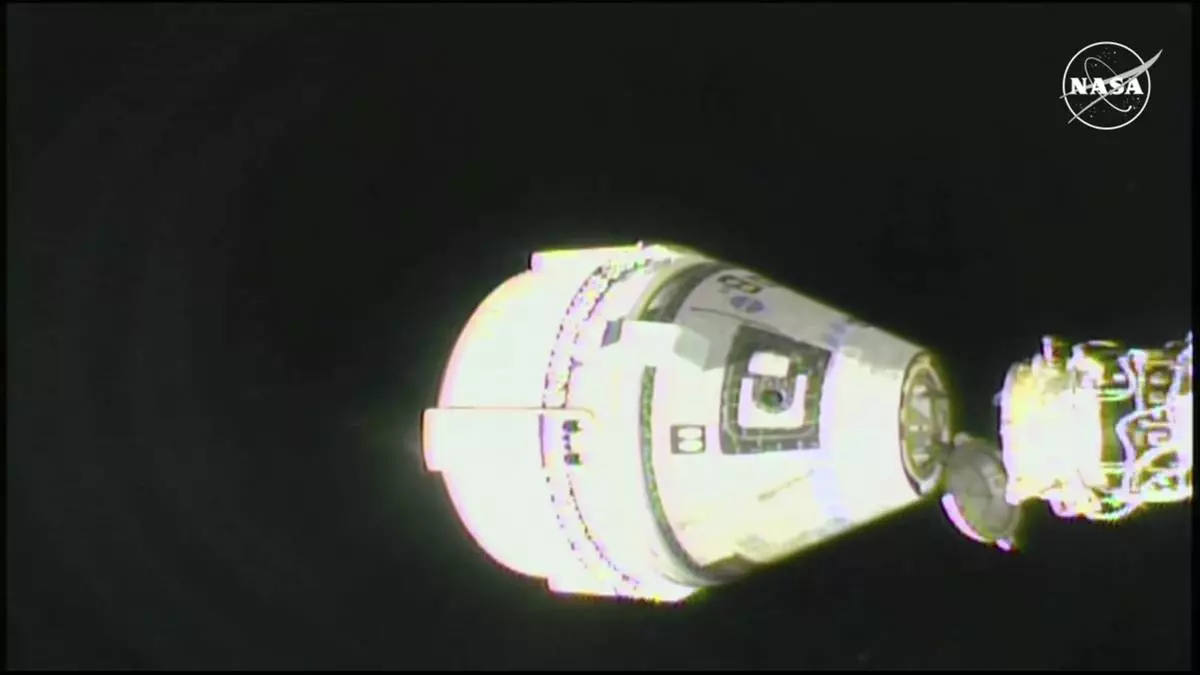

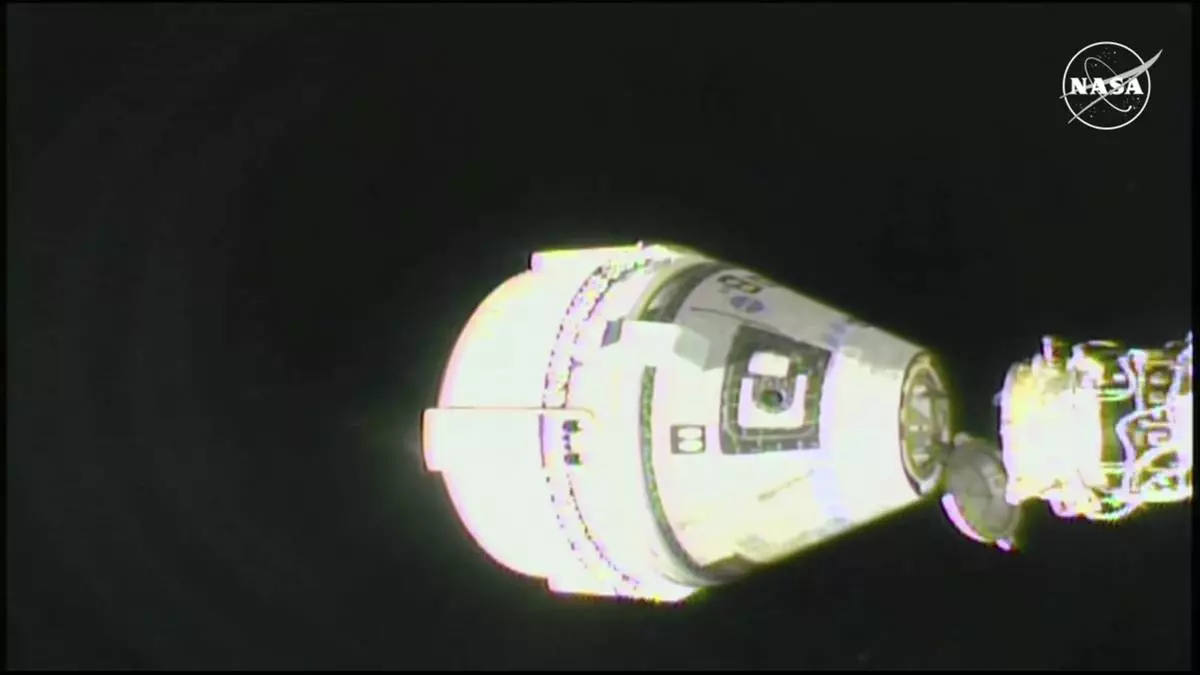

Boeing’s first astronaut mission ended Friday night with an empty capsule landing and two test pilots still in space, left behind until next year because NASA judged their return too risky.

Six hours after departing the International Space Station, Starliner parachuted into New Mexico’s White Sands Missile Range, descending on autopilot through the desert darkness.

It was an uneventful close to a drama that began with the June launch of Boeing's long-delayed crew debut and quickly escalated into a dragged-out cliffhanger of a mission stricken by thruster failures and helium leaks. For months, Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams’ return was in question as engineers struggled to understand the capsule’s problems.

Boeing insisted after extensive testing that Starliner was safe to bring the two home, but NASA disagreed and booked a flight with SpaceX instead. Their SpaceX ride won’t launch until the end of this month, which means they’ll be up there until February — more than eight months after blasting off on what should have been a quick trip.

Wilmore and Williams should have flown Starliner back to Earth by mid-June, a week after launching in it. But their ride to the space station was marred by the cascade of thruster trouble and helium loss, and NASA ultimately decided it was too risky to return them on Starliner.

So with fresh software updates, the fully automated capsule left with their empty seats and blue spacesuits along with some old station equipment.

“She’s on her way home,” Williams radioed as the white and blue-trimmed capsule undocked from the space station 260 miles (420 kilometers) over China and disappeared into the black void.

Williams stayed up late to see how everything turned out. “A good landing, pretty awesome,” said Boeing's Mission Control.

Cameras on the space station and a pair of NASA planes caught the capsule as a white streak coming in for the touchdown, which drew cheer.

There were some snags during reentry, including more thruster issues, but Starliner made a “bull’s-eye landing,” said NASA’s commercial crew program manager Steve Stich.

Even with the safe return, “I think we made the right decision not to have Butch and Suni on board,” Stich said at a news conference early Saturday. “All of us feel happy about the successful landing. But then there's a piece of us, all of us, that we wish it would have been the way we had planned it.”

Boeing did not participate in the Houston news briefing. But two of the company's top space and defense officials, Ted Colbert and Kay Sears, told employees in a note that they backed NASA's ruling.

"While this may not have been how we originally envisioned the test flight concluding, we support NASA’s decision for Starliner and are proud of how our team and spacecraft performed," the executives wrote.

Starliner’s crew demo capped a journey filled with delays and setbacks. After the space shuttles retired more than a decade ago, NASA hired Boeing and SpaceX for orbital taxi service. Boeing ran into so many problems on its first test flight with no one aboard in 2019 that it had to repeat it. The 2022 do-over uncovered even more flaws and the repair bill topped $1 billion.

SpaceX’s crew ferry flight later this month will be its 10th for NASA since 2020. The Dragon capsule will launch on the half-year expedition with only two astronauts since two seats are reserved for Wilmore and Williams for the return leg.

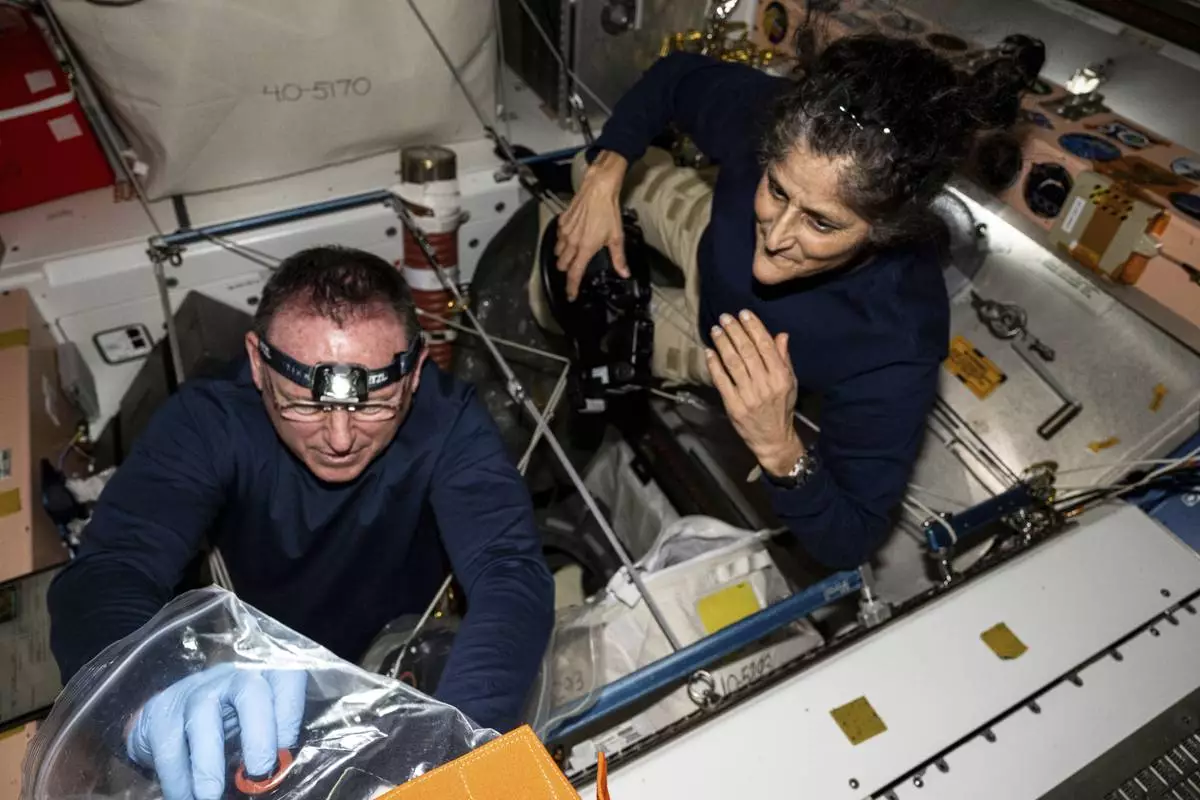

As veteran astronauts and retired Navy captains, Wilmore and Williams anticipated hurdles on the test flight. They’ve kept busy in space, helping with repairs and experiments. The two are now full-time station crew members along with the seven others on board.

Even before the pair launched on June 5 from Cape Canaveral, Florida, Starliner’s propulsion system was leaking helium. The leak was small and thought to be isolated, but four more cropped up after liftoff. Then five thrusters failed. Although four of the thrusters were recovered, it gave NASA pause as to whether more malfunctions might hamper the capsule’s descent from orbit.

Boeing conducted numerous thruster tests in space and on the ground over the summer, and was convinced its spacecraft could safely bring the astronauts back. But NASA could not get comfortable with the thruster situation and went with SpaceX.

Flight controllers conducted more test firings of the capsule’s thrusters following undocking; one failed to ignite. Engineers suspect the more the thrusters are fired, the hotter they become, causing protective seals to swell and obstruct the flow of propellant. They won’t be able to examine any of the parts; the section holding the thrusters was ditched just before reentry.

Starliner will be transported in a couple weeks back to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, where the analyses will unfold.

NASA officials stressed that the space agency remains committed to having two competing U.S. companies transporting astronauts. The goal is for SpaceX and Boeing to take turns launching crews — one a year per company — until the space station is abandoned in 2030 right before its fiery reentry. That doesn’t give Boeing much time to catch up, but the company intends to push forward with Starliner, according to NASA.

Stich said post-landing it’s too early to know when the next Starliner flight with astronauts might occur.

“It will take a little time to determine the path forward," he said.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

The empty Boeing Starliner capsule sits at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, late Friday, Sept. 6, 2024, after undocking from the International Space Station. (Boeing via AP)

In this image from video provided by NASA, the empty Boeing Starliner capsule jettisons its heat shield, bottom, before touching down at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico late Friday, Sept. 6, 2024, after undocking from the International Space Station. (NASA via AP)

In this image from video provided by NASA, the empty Boeing Starliner capsule floats down towards White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico late Friday, Sept. 6, 2024, after undocking from the International Space Station. (NASA via AP)

In this image from video provided by NASA, the empty Boeing Starliner capsule touches down at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico late Friday, Sept. 6, 2024, after undocking from the International Space Station. (NASA via AP)

In this image from video provided by NASA, the unmanned Boeing Starliner capsule undocks as it pulls away from the International Space Station on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (NASA via AP)

In this image from video provided by NASA, the unmanned Boeing Starliner capsule fires its thrusters as it pulls away from the International Space Station on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (NASA via AP)

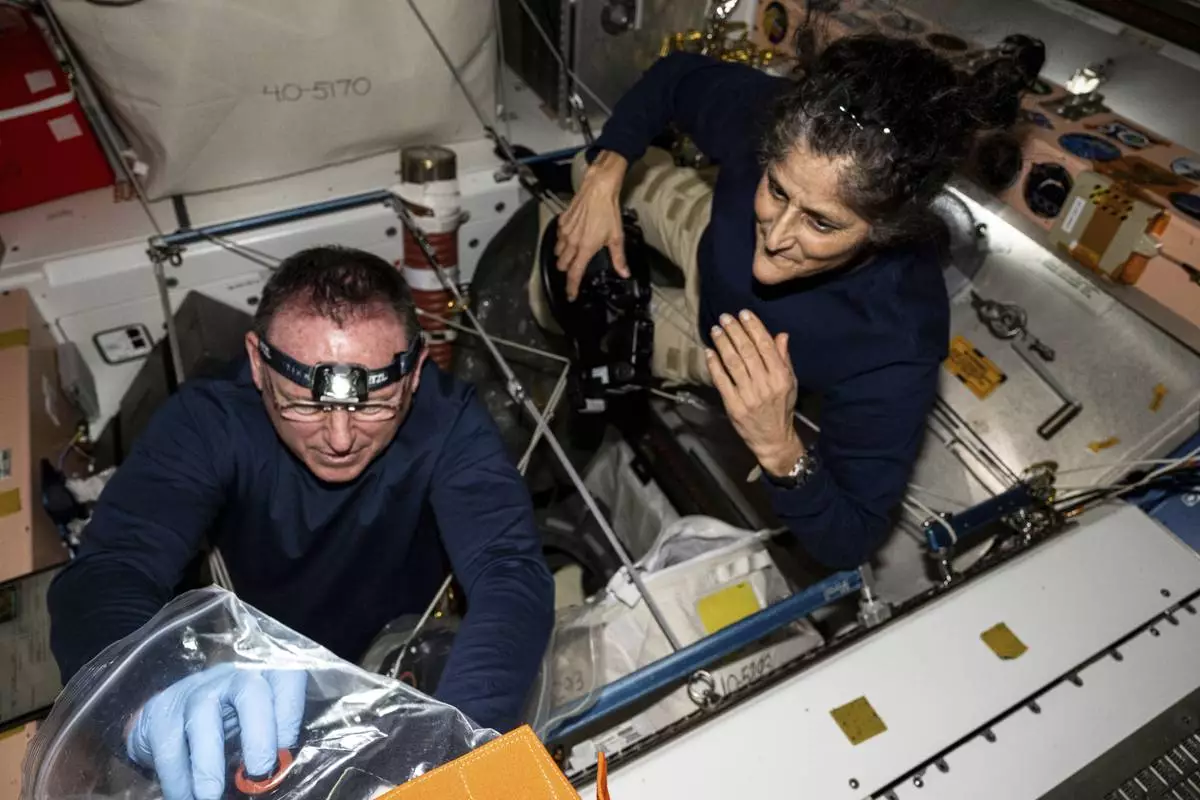

In this photo provided by NASA, astronauts Butch Wilmore, left, and Suni Williams inspect safety hardware aboard the International Space Station on Aug. 9, 2024. (NASA via AP)