A pair of Syrians have created a community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war.

Founded in 2018 as a “humanitarian catering service," HummusTown was originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria.

Click to Gallery

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, right, talks to Jumana Farho, from Syria, as they work in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

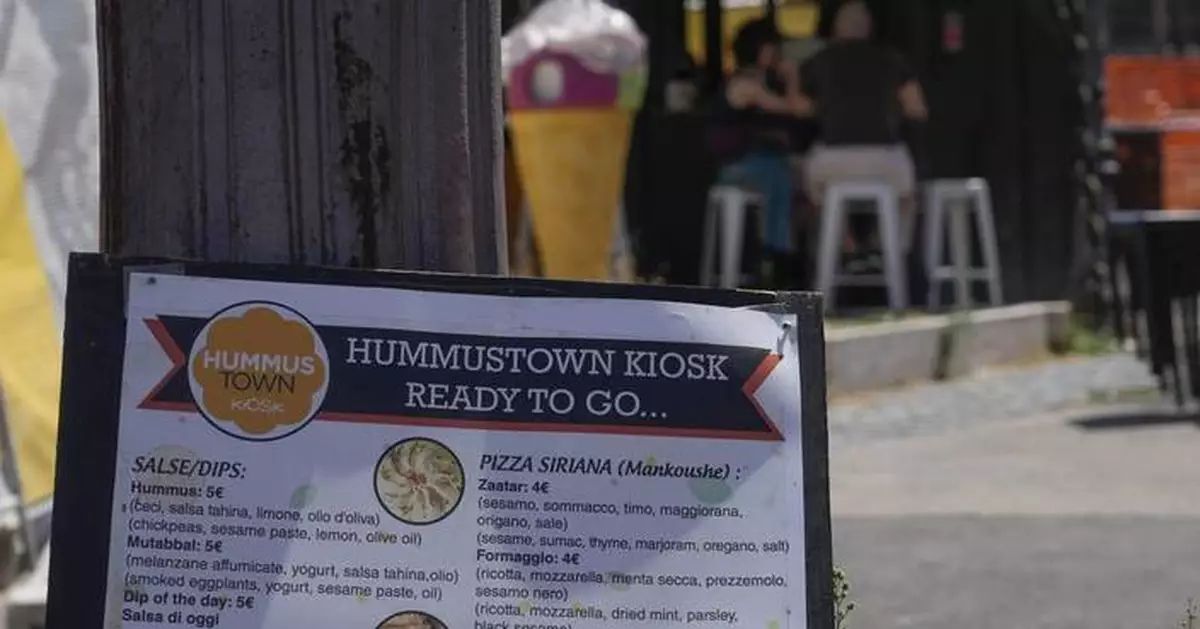

Customers enjoy hummus outside the HummusTown bistro in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Jumana Farho, from Syria, prepares Kunafa a traditional Syrian cake in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Shaza Saker, of Syria, right, serves hummus to customers outside the HummusTown bistro in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Jumana Farho, from Syria, prepares Kunafa a traditional Syrian cake in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, prepares boxes of falafel in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, prepares boxes of falafel in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Jumana Farho, from Syria, holds slices of bread as she works in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, right, talks to Jumana Farho, from Syria, as they work in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, works in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, prepares falafel in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, works in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

A falafel wrapped in bread is warmed up at a HummusTown kiosk in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

A menu is displayed outside a HummusTown kiosk in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

It has since grown into a successful small business that has shifted from sending remittances to helping new migrants integrate in Italy, all the while gaining a steady following on Rome’s gastronomic scene.

As the Syrian war continued to rage, Shaza Saker, a long-time U.N. employee living in Rome, and Joumana Farho, who was working as her cook, wanted to find a way to help people at home. Farho, 48, brought her "divine'' cooking, while Saker, 49, networked.

“I told her: ‘Let’s start inviting people over for dinner ... and whatever we make out of these dinners we’ll just send to Syria," Saker said. “My house had become a bit of, you know, a restaurant, a home restaurant. But it was fun. We felt useful.”

The non-profit that started with 45,000 euros ($48,670) raised through crowdfunding now employs 13 full-time and 10 part-time staff at its kitchen kiosk near Rome's train station and a small bistro, with plans to open a restaurant.

The expanded group now also organizes cooking classes, cultural events and summer aperitifs, as well as catering for events in the Italian capital.

Each month, they donate food to the homeless and last year they raised 40,000 euros for victims of the earthquakes that struck Syria on Feb. 6, 2023 with the loss of thousands of lives.

As more refugees arrived in Rome, the two shifted their focus to providing Syrian asylum-seekers with work and a support network, eventually expanding their mission to all vulnerable people, including Italians.

They include Mayyada al-Amrani, a Palestinian woman who fled Gaza with her eldest daughter, who is getting treatment for cancer. She spends her days rolling traditional spiced rice into grape leaves, working alongside four other cooks of Syrian and Palestinian origin. While she is able to earn money to help support herself and her daughter in Italy, she worries about her five other children back in Gaza, the youngest not yet 9 months old.

“They are surviving,'' she said. ”They struggle and suffer mostly from (lack of) water."

Fadi Salem, now HummusTown's manager, is a Syrian refugee from Damascus who arrived in Rome in 2022 after living in Lebanon for seven years. Salem discovered the humanitarian catering service through Rome’s Syrian community and said it gradually became a family for him.

“I found integration through HummusTown instead of finding it through the migration centers,'' he said. "Because from my position here I speak with many Italian and foreign clients, so I practice my Italian, English and Arabic every day,” he noted.

Customers enjoy hummus outside the HummusTown bistro in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Jumana Farho, from Syria, prepares Kunafa a traditional Syrian cake in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Shaza Saker, of Syria, right, serves hummus to customers outside the HummusTown bistro in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Jumana Farho, from Syria, prepares Kunafa a traditional Syrian cake in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, prepares boxes of falafel in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, prepares boxes of falafel in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Jumana Farho, from Syria, holds slices of bread as she works in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, right, talks to Jumana Farho, from Syria, as they work in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, works in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, prepares falafel in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Ruqaia Agha, a Palestinian woman from Ramla, works in the HummusTown kitchen in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

A falafel wrapped in bread is warmed up at a HummusTown kiosk in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

A menu is displayed outside a HummusTown kiosk in Rome, Saturday, July 27, 2024. A pair of Syrians have created community that provides support to migrants and vulnerable people in Rome, by sharing the flavors of a homeland torn by civil war. Created in 2018 as a "humanitarian catering service," HummusTown originally aimed at raising funds for families and friends in Syria. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

ISTANBUL (AP) — The Turkish doctor at the center of an alleged fraud scheme that led to the deaths of 10 babies told an Istanbul court Saturday that he was a “trusted” physician.

Dr. Firat Sari is one of 47 people on trial accused of transferring newborn babies to neonatal units of private hospitals, where they were allegedly kept for prolonged and sometimes unnecessary treatments in order to receive social security payments.

“Patients were referred to me because people trusted me. We did not accept patients by bribing anyone from 112,” Sari said, referring to Turkey’s emergency medical phone line.

Sari, said to be the plot’s ringleader, operated the neonatal intensive care units of several private hospitals in Istanbul. He is facing a sentence of up to 583 years in prison in a case where doctors, nurses, hospital managers and other health staff are accused of putting financial gain before newborns’ wellbeing.

The case, which emerged last month, has sparked public outrage and calls for greater oversight of the health care system. Authorities have since revoked the licenses and closed 10 of the 19 hospitals that were implicated in the scandal.

“I want to tell everything so that the events can be revealed,” Sari, the owner of Medisense Health Services, told the court. “I love my profession very much. I love being a doctor very much.”

Although the defendants are charged with the negligent homicide of 10 infants since January 2023, an investigative report cited by the state-run Anadolu news agency said they caused the deaths of “hundreds” of babies over a much longer time period.

Over 350 families have petitioned prosecutors or other state institutions seeking investigations into the deaths of their children, according to state media.

Prosecutors at the trial, which opened on Monday, say the defendants also falsified reports to make the babies’ condition appear more serious so as to obtain more money from the state as well as from families.

The main defendants have denied any wrongdoing, insisting they made the best possible decisions and are now facing punishment for unavoidable, unwanted outcomes.

Sari is charged with establishing an organization with the aim of committing a crime, defrauding public institutions, forgery of official documents and homicide by negligence.

During questioning by prosecutors before the trial, Sari denied accusations that the babies were not given the proper care, that the neonatal units were understaffed or that his employees were not appropriately qualified, according to a 1,400-page indictment.

“Everything is in accordance with procedures,” he told prosecutors in a statement.

The hearings at Bakirkoy courthouse, on Istanbul’s European side, have seen protests outside calling for private hospitals to be shut down and “baby killers” to be held accountable.

The case has also led to calls for the resignation of Health Minister Kemal Memisoglu, who was the Istanbul provincial health director at the time some of the deaths occurred. Ozgur Ozel, the main opposition party leader, has called for all hospitals involved to be nationalized.

In a Saturday interview with the A Haber TV channel, Memisoglu characterized the defendants as “bad apples” who had been “weeded out.”

“Our health system is one of the best health systems in the world,” he said. “This is a very exceptional, very organized criminal organization. It is a mistake to evaluate this in the health system as a whole.”

Memisoglu also denied the claim that he shut down an investigation into the claims in 2016, when he was Istanbul’s health director, calling it “a lie and slander.”

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said this week that those responsible for the deaths would be severely punished but warned against placing all the blame on the country’s health care system.

“We will not allow our health care community to be battered because of a few rotten apples,” he said.

Activists chant slogans during a protest outside the courthouse where dozens of Turkish healthcare workers including doctors and nurses go on trial for fraud and causing the deaths of 10 infants, in Istanbul, Turkey, Monday Nov, 18, 2024.(AP Photo/Khalil Hamra)

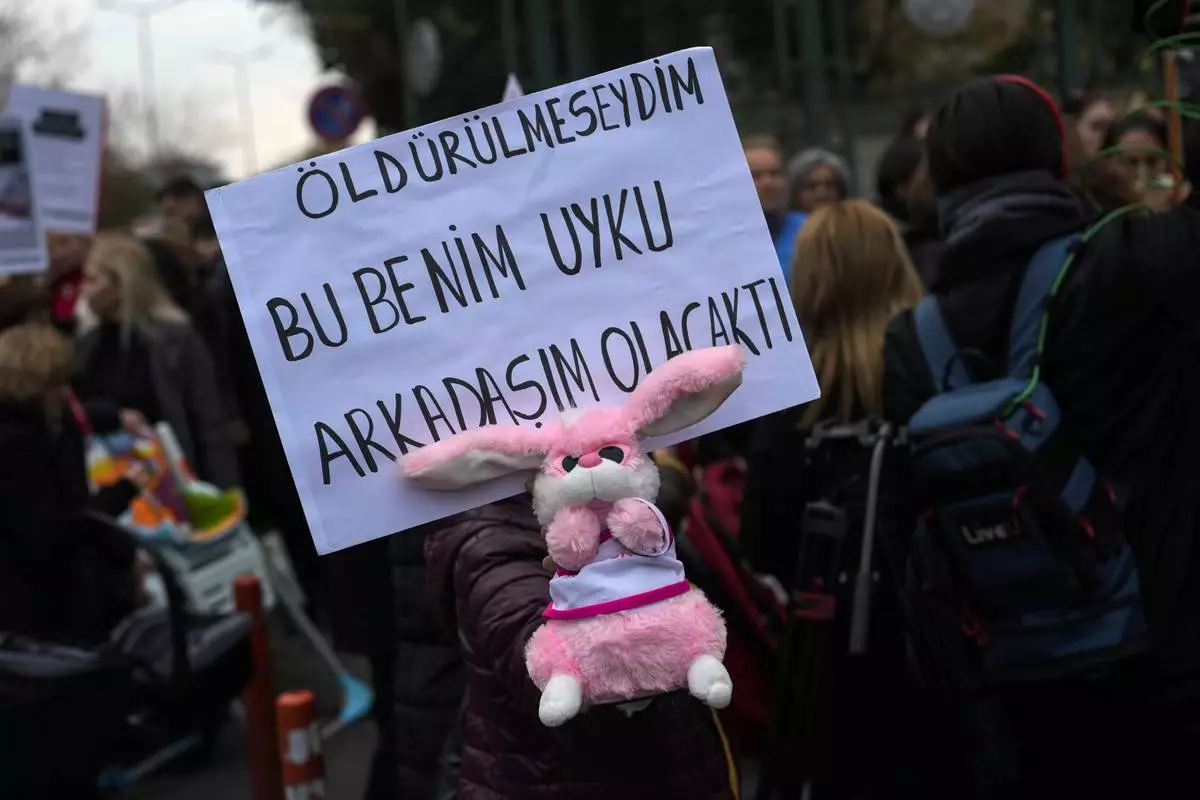

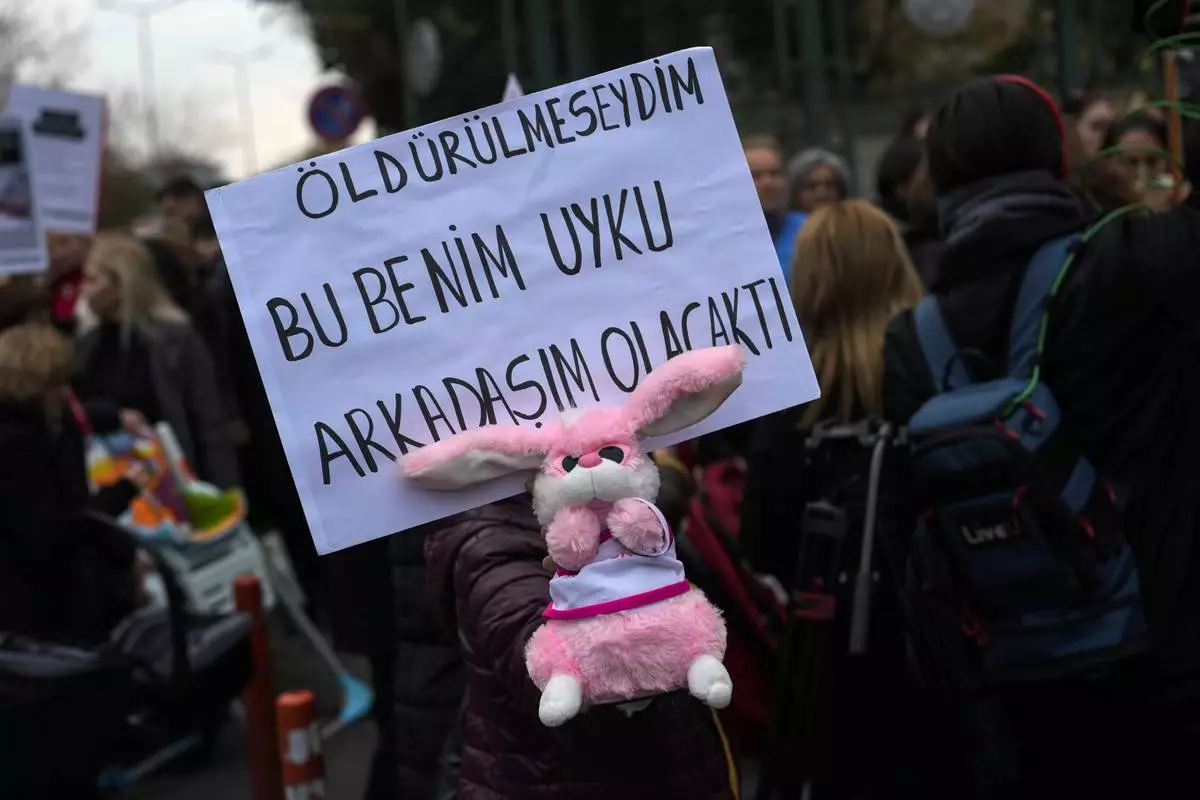

Activists, some holding banners with Turkish writing that some of them reads, " Children should not be killed , so they can eat candies", " I couldn't play with my toys because I was killed" and " If I had not been killed this toy would have been my sleeping friend " during a protest outside the courthouse where dozens of Turkish healthcare workers including doctors and nurses go on trial for fraud and causing the deaths of 10 infants, in Istanbul, Turkey, Monday Nov, 18, 2024.(AP Photo/Khalil Hamra)

An activist holds a baby toy and a banner with Turkish writing that reads, "If I had not been killed this would have been my sleeping friend" during a protest outside the courthouse where dozens of Turkish healthcare workers including doctors and nurses go on trial for fraud and causing the deaths of 10 infants, in Istanbul, Turkey, Monday Nov, 18, 2024.(AP Photo/Khalil Hamra)

Activists some holding banners with Turkish writing that read, " Children should not be killed , so they can eat candies", " I couldn't play with my toys because I was killed" and " If I had not been killed this toy would have been my sleeping friend " during a protest outside the courthouse where dozens of Turkish healthcare workers including doctors and nurses go on trial for fraud and causing the deaths of 10 infants, in Istanbul, Turkey, Monday Nov, 18, 2024.(AP Photo/Khalil Hamra)