PARIS (AP) — Female in their passports, female at the Paris Olympics.

The International Olympic Committee on Tuesday defended the right of two athletes to compete in women’s boxing despite being judged last year to have failed gender eligibility tests at the world championships.

Lin Yu-ting of Taiwan, who is a two-time world champion, and Imane Khelif of Algeria are both competing at their second Olympics.

“Everyone competing in the women’s category is complying with the competition eligibility rules,” IOC spokesman Mark Adams said Tuesday at the daily news conference by organizers of the Paris Olympics.

“They are women in their passports and it’s stated that this is the case, that they are female,” Adams said.

At the 2023 worlds in New Delhi, both were due to get medals until being disqualified by the International Boxing Association. The IBA has no part in running Olympic boxing in fallout from a years-long dispute with the IOC.

Paris Olympics boxing is being run by officials appointed by the IOC, which said Monday it is using rule books based on the version that applied at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics.

“They are eligible by the rules of the federation which was set in 2016, and which worked for Tokyo too,” Adams said. “To compete as women, which is what they are. And we fully support that.”

The IOC official said it would be “invidious and unfair” to discuss details of individual athletes.

Lin is top-seeded in the women’s 57-kilogram featherweight class and Khelif is the No. 5 seed in the 66-kilogram welterweight event.

On Thursday, Khelif will fight Italy’s Angela Carini at the North Paris Arena. Lin has a first-round bye and will face Uzbekistan’s Sitora Turdibekova on Friday.

Lin qualified for Paris by winning the Asian Games title last October and Khelif won an African qualifying tournament last September. Both qualification tournaments were held under the IOC’s authority months after the fighters’ exclusion from the IBA-run worlds.

Khelif was removed from her gold-medal bout in India for having elevated levels of testosterone, the IOC's athlete database in Paris said. Lin failed “a biochemical test” at the 2023 worlds.

Their presence in Paris drew criticism this week, with former men’s featherweight world champion Barry McGuigan posting on social media “it’s shocking that they were actually allowed to get this far.”

The 28-year-old Lin won her first world title in 2018 and was a youth world champion in 2013, according to an IBA profile. In 2021, Khelif was a quarterfinalist at the Tokyo Olympics, losing to eventual champion Kellie Harrington of Ireland.

“These athletes have competed many times before for many years. They haven’t just suddenly arrived,” Adams said.

Since the Tokyo Olympics, sports bodies including World Aquatics, World Athletics and the International Cycling Union have updated their gender rules. They now ban athletes who went through male puberty from competing in women’s events.

The track body also last year tightened rules on athletes with differences in sex development (DSD). They include two-time Olympic 800-meter champion Caster Semenya, who has not run in that event since 2019.

The IOC gave those governing bodies guidance in 2021 without imposing rules, in what Adams said Tuesday is an “incredibly complex” subject for experts in each Olympic sport to assess.

AP Summer Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/2024-paris-olympic-games

FILE - Imane Khelif, of Algeria, right, delivers a punch to Mariem Homrani Ep Zayani, of Turkey, during their women's light weight 60kg preliminary boxing match at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Friday, July 30, 2021, in Tokyo, Japan. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

FILE - Taiwan's Lin Yu-ting poses after winning against India's Parveen in the Boxing Women's 54-57Kg Semifinal bout during the 19th Asian Games in Hangzhou, China, Wednesday, Oct. 4, 2023. (AP Photo/Aijaz Rahi, File)

What's in a name change, after all?

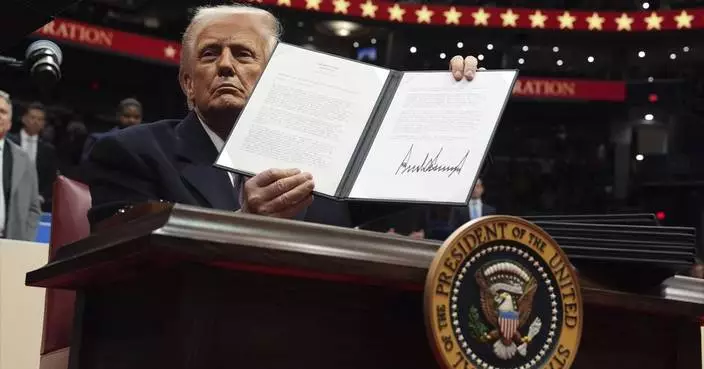

The water bordered by the Southern United States, Mexico and Cuba will be critical to shipping lanes and vacationers whether it’s called the Gulf of Mexico, as it has been for four centuries, or the Gulf of America, as President Donald Trump ordered this week. North America’s highest mountain peak will still loom above Alaska whether it’s called Mt. Denali, as ordered by former President Barack Obama in 2015, or changed back to Mt. McKinley as Trump also decreed.

But Trump's territorial assertions, in line with his “America First” worldview, sparked a round of rethinking by mapmakers and teachers, snark on social media and sarcasm by at least one other world leader. And though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis put the Trumpian “Gulf of America” on an official document and some other gulf-adjacent states were considering doing the same, it was not clear how many others would follow Trump's lead.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum joked that if Trump went ahead with the renaming, her country would rename North America “Mexican America.” On Tuesday, she toned it down: “For us and for the entire world it will continue to be called the Gulf of Mexico.”

Map lines are inherently political. After all, they're representations of the places that are important to human beings — and those priorities can be delicate and contentious, even more so in a globalized world.

There’s no agreed-upon scheme to name boundaries and features across the Earth.

“Denali” is the mountain's preferred name for Alaska Natives, while “McKinley" is a tribute to President William McKinley, designated in the late 19th century by a gold prospector. China sees Taiwan as its own territory, and the countries surrounding what the United States calls the South China Sea have multiple names for the same body of water.

The Persian Gulf has been widely known by that name since the 16th century, although usage of “Gulf” and “Arabian Gulf” is dominant in many countries in the Middle East. The government of Iran — formerly Persia — threatened to sue Google in 2012 over the company’s decision not to label the body of water at all on its maps. Many Arab countries don’t recognize Israel and instead call it Palestine. And in many official releases, Israel calls the occupied West Bank by its biblical name, “Judea and Samaria.”

Americans and Mexicans diverge on what to call another key body of water, the river that forms the border between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. Americans call it the Rio Grande; Mexicans call it the Rio Bravo.

Trump's executive order — titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness” — concludes thusly: “It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes. The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our Nation’s rich past.”

But what to call the gulf with the 3,700-mile coastline?

“It is, I suppose, an internationally recognized sea, but (to be honest), a situation like this has never come up before so I need to confirm the appropriate convention,” said Peter Bellerby, who said he was talking over the issue with the cartographers at his London company, Bellerby & Co. Globemakers. “If, for instance, he wanted to change the Atlantic Ocean to the American Ocean, we would probably just ignore it."

As of Wednesday night, map applications for Google and Apple still called the mountain and the gulf by their old names. Spokespersons for those platforms did not immediately respond to emailed questions.

A spokesperson for National Geographic, one of the most prominent map makers in the U.S., said this week that the company does not comment on individual cases and referred questions to a statement on its web site, which reads in part that it "strives to be apolitical, to consult multiple authoritative sources, and to make independent decisions based on extensive research.” National Geographic also has a policy of including explanatory notes for place names in dispute, citing as an example a body of water between Japan and the Korean peninsula, referred to as the Sea of Japan by the Japanese and the East Sea by Koreans.

In discussion on social media, one thread noted that the Sears Tower in Chicago was renamed the Willis Tower in 2009, though it's still commonly known by its original moniker. Pennsylvania's capital, Harrisburg, renamed its Market Street to Martin Luther King Boulevard and then switched back to Market Street several years later — with loud complaints both times. In 2017, New York's Tappan Zee Bridge was renamed for the late Gov. Mario Cuomo to great controversy. The new name appears on maps, but “no one calls it that,” noted another user.

“Are we going to start teaching this as the name of the body of water?” asked one Reddit poster on Tuesday.

“I guess you can tell students that SOME PEOPLE want to rename this body of water the Gulf of America, but everyone else in the world calls it the Gulf of Mexico,” came one answer. “Cover all your bases — they know the reality-based name, but also the wannabe name as well.”

Wrote another user: “I'll call it the Gulf of America when I'm forced to call the Tappan Zee the Mario Cuomo Bridge, which is to say never.”

FILE - President Donald Trump speaks in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Peter Bellerby, the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, holds a globe at a studio in London, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - A boat is seen on the Susitna River near Talkeetna, Alaska, on Sunday, June 13, 2021, with Denali in the background. Denali, the tallest mountain on the North American continent, is located about 60 miles northwest of Talkeetna. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen, File)

FILE - The water in the Gulf of Mexico appears bluer than usual off of East Beach, Saturday, June 24, 2023, in Galveston, Texas. (Jill Karnicki/Houston Chronicle via AP, File)