GAINESVILLE, Fla. (AP) — William Laws Calley Jr., who as an Army lieutenant led the U.S. soldiers who killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre, the most notorious war crime in modern American military history, has died. He was 80.

Calley died on April 28, according to his Florida death record, which said he had been living in an apartment in Gainesville. His death was first reported by The Washington Post on Monday, citing his death certificate.

Calley had lived in obscurity in the decades since he was court-martialed and convicted in 1971, the only one of 25 men originally charged to be found guilty in the massacre that helped turn American opinion against the war in Vietnam.

On March 16, 1968, Calley led American soldiers of the Charlie Company on a mission to confront a crack outfit of Vietcong enemies. Instead, over several hours, the soldiers killed 504 unresisting civilians, mostly women, children and elderly men, in My Lai and a neighboring community.

The men were angry: Two days earlier, a booby trap had killed a sergeant, blinded a GI and wounded several others while Charlie Company was on patrol.

Soldiers eventually testified to the U.S. Army investigating commission that the murders began soon after Calley led Charlie Company’s first platoon into My Lai that morning. Some were bayoneted to death. Families were herded into bomb shelters and killed with hand grenades. Other civilians slaughtered in a drainage ditch. Women and girls were gang-raped.

It wasn’t until more than a year later that news of the massacre became public. And while My Lai was the most notorious massacre in modern U.S. military history, it was not an aberration: Estimates of civilians killed during the U.S. ground war in Vietnam from 1965 to 1973 range from 1 million to 2 million.

The U.S. military’s own records, filed away for three decades, described 300 other cases of what could fairly be described as war crimes. My Lai stood out because of the shocking one-day death toll, stomach-churning photographs and gruesome details exposed by a high-level U.S. Army inquiry.

Investigations into the massacre and allegations of a Pentagon coverup were launched after a complaint by a helicopter pilot, Hugh Thompson Jr., who saved 16 Vietnamese children in the village and later testified against Calley.

Multiple other soldiers at the scene also spoke out after the scandal broke. Some said civilian deaths were inevitable in a war where the enemy could be anywhere. Others said Calley, who was charged with killing 109 civilians, shouldn’t have been singled out.

“Calley, he didn’t kill the 109 all by himself. There was a company there,” said Herbert Carter, a soldier from Houston. “We went through the village. We didn’t see any VC (Viet Cong). People came out of their hootches (huts) and the guys shot them down and then burned the hootches, or burned the hootches and then shot the people when they came out. ... It went on like this all day. Some of the guys seemed to be having a lot of fun doing it.”

Calley was convicted in 1971 for the murders of 22 people during the rampage. He was sentenced to life in prison but served only three days because President Richard Nixon ordered his sentence reduced. He served three years of house arrest.

Without apologizing, much less admitting guilt, Calley mused about the massacre's legacy in an exclusive Associated Press interview as he waited for the verdict.

“I can’t say I’m proud of ever being in My Lai or ever participating in war. But I would be extremely proud if My Lai shows the world what war is and that the world needs to do something about stopping wars,” he said. “I hope My Lai isn’t a tragedy but an eye opener ... My Lai has happened in every war. It’s not an isolated incident, even in Vietnam.”

After his release, Calley got married, settled into a job at his father-in-law's jewelry store in Columbus and had a son. He later got divorced and moved to Atlanta, where he avoided publicity and routinely turned down journalists’ requests for interviews.

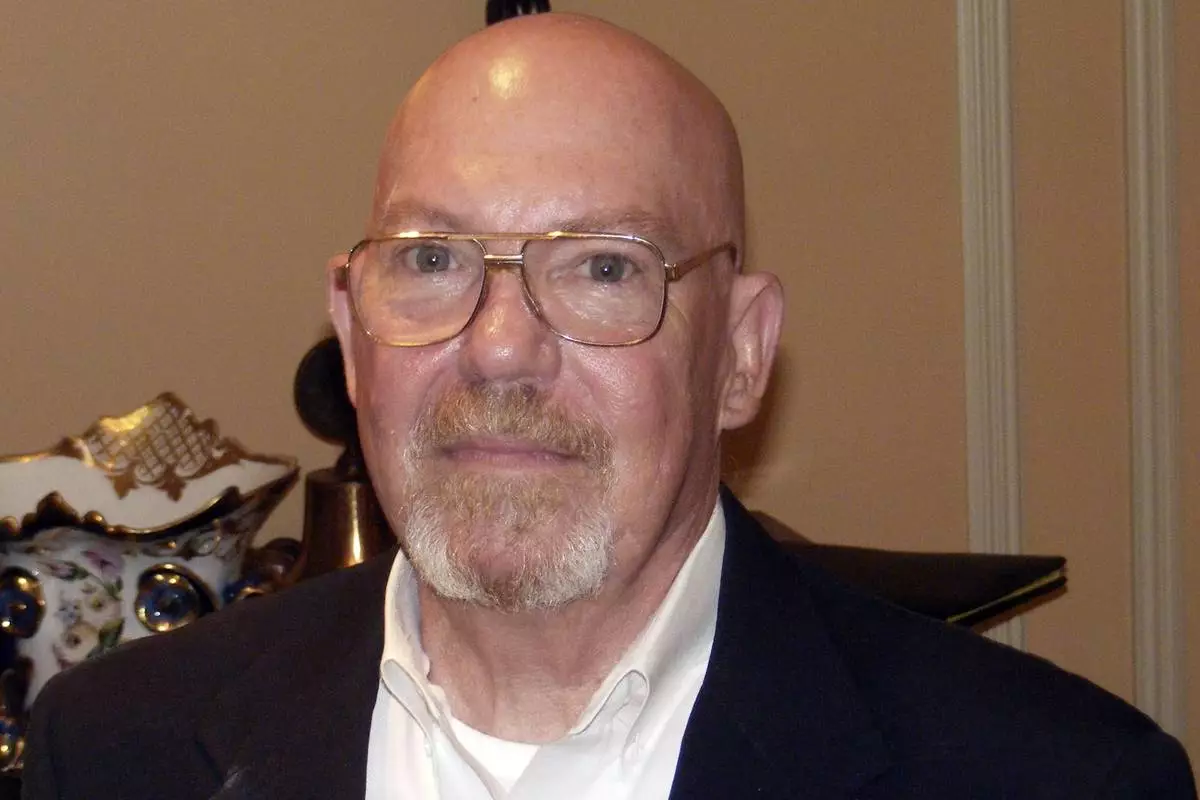

Calley broke his silence in 2009, at the urging of a friend, when he spoke to the Kiwanis Club in Columbus, Georgia, near Fort Benning, where he had been court-martialed.

“There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai,” Calley said, according to the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer. “I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.”

He said his mistake was following orders, which had been his defense when he was tried. His superior officer was acquitted.

John Partin, the assistant prosecutor at the court-martial, learned of Calley's death in a phone call from an AP reporter Tuesday. He recalled being disappointed in Nixon’s response to Calley's conviction, and rejected the notion that Calley was simply a scapegoat for command decisions or U.S. policy failures.

“He was acting essentially on his own, although he, like the others, said it was following orders,” Partin said. “His responsibility as an officer was to not obey unlawful orders, and the order he says they got was illegal.”

Partin said one of most important outcomes of the My Lai massacre was the recognition that U.S. troops needed to be better trained in the rules of engagement and the legal implications of combat actions.

“It became the standard to have better education for our troops,” he said.

In a 1976 AP interview, the former Army colonel who presided over Calley's court-martial said he believed that Calley thought he was doing the right thing at My Lai, but he was still guilty, and others who knew of and participated in the killings should have been convicted as well.

Calley was born in June 8, 1943 in South Florida, where friends called him “Rusty” growing up. He eventually dropped out of Palm Beach Junior College, and worked as a dishwasher, bellhop, railroad switchman, salesman and insurance appraiser before joining the Army in 1966.

At about 5-foot, 3-inches tall and 120 pounds when he was in the Army, Calley didn't stand out. Fellow officer candidates told the AP in 1969 that there was nothing unusual about him. But his military career was advancing until the scandal. Months after the massacre, he returned home, then re-upped for another tour. Eventually, he was wounded, awarded the Purple Heart, and won two Bronze Star medals.

His sister Dawn was living with their father in a mobile home in Hialeah when she told reporters during the trial that her brother was a “sweet, sensitive guy.”

Messages left for his son and ex-wife on Tuesday were not immediately returned.

FILE - Lt. William L. Calley Jr., center, and his military counsel, Maj. Kenneth A. Raby, left, arrive the Pentagon for testimony before an Army board of investigation on the alleged My Lai Massacre in Washington on Dec. 6, 1969. Calley, who as an Army lieutenant led the U.S. soldiers who killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre, the most notorious war crime in modern American military history, died on April 28 at a hospice center in Gainesville, Fla., The Washington Post reported Monday July 29, 2024, citing his death certificate. He was 80. (AP Photo/File)

FILE - Lt. William Calley leaves the court martial building at Fort McPherson, Ga., Sept. 13, 1971 after being allowed to invoke his constitutional privileges and not testify in the trial of Capt. Ernest Medina. Calley, who as an Army lieutenant led the U.S. soldiers who killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre, the most notorious war crime in modern American military history, died on April 28 at a hospice center in Gainesville, Fla., The Washington Post reported Monday July 29, 2024, citing his death certificate. He was 80. (AP Photo/Mark Foley, File)

FILE - Former Army Lt. William Calley poses for a photo at the Kiwanis Club, Aug. 19, 2009, in Columbus, Ga. where he spoke publicly for the first time about the My Lai massacre in Vietnam in 1968. Calley, who as an Army lieutenant led the U.S. soldiers who killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre, the most notorious war crime in modern American military history, died on April 28 at a hospice center in Gainesville, Fla., The Washington Post reported Monday July 29, 2024, citing his death certificate. He was 80. (The Ledger-Enquirer via AP, File)

FILE - Lt. William L. Calley, Jr., pictured during his court martial at Fort Benning, Ga., on April 23, 1971. Calley, who as an Army lieutenant led the U.S. soldiers who killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians in the My Lai massacre, the most notorious war crime in modern American military history, died on April 28 at a hospice center in Gainesville, Fla., The Washington Post reported Monday July 29, 2024, citing his death certificate. He was 80. (APPhoto/Joe Holloway, Jr., File)