CLARKSBURG, W.Va. (AP) — An inmate was sentenced to more than four years Thursday for his role in the 2018 fatal bludgeoning of notorious Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger in a troubled West Virginia federal prison.

Massachusetts gangster Paul J. DeCologero was sentenced in federal court after pleading guilty to an assault charge. He could have faced up to 10 years in prison. DeCologero was already serving a 25-year sentence handed down in 2006 after he was convicted of buying heroin used to try to kill a teenage girl.

Prosecutors initially had said DeCologero and inmate Fotios “Freddy” Geas used a lock attached to a belt to repeatedly hit the 89-year-old Bulger in the head hours after he arrived at USP Hazelton from another lockup in Florida. But on Thursday, both prosecutors and the defense said DeCologero only served as a lookout and had not physically assaulted Bulger.

U.S. District Judge Thomas Kleeh said the sentence was “fair, just and appropriate” and “strikes the balance the court is trying to seek.”

DeCologero, 50, declined to speak when given the opportunity to address the court. Defense attorney Patrick Nash began by conveying an apology from DeCologero to Bulger's family as well as the inmate's own relatives.

Nash described DeCologero as the victim of an “abusive and neglectful” upbringing.

“Paul has had an incredibly difficult life,” Nash said. “As a result of that, Paul is a person who is easily led. Anyone who shows him attention, he's easily led.”

An uncle eventually took in DeCologero and made him part of a criminal organization, Nash said.

In Bulger's killing, “Paul was involved," Nash said. "He is guilty. But his role was limited.”

Assistant U.S. Attorney Brandon Flower declined to comment after the sentencing.

According to court records, inmates found out ahead of time that Bulger would be arriving at Hazelton. An inmate previously told a grand jury that DeCologero said to him that Bulger was a snitch and they planned to kill him as soon as he came into their unit.

Prosecutors have said DeCologero and Geas spent about seven minutes in Bulger’s cell. Geas hit Bulger, while DeCologero served as a lookout and helped cover Bulger's body, Flower said Thursday. DeCologero's DNA was found on two blankets, the prosecutor said.

Geas has been charged with murder and conspiracy to commit first-degree murder, which carries up to a life sentence. His hearing is scheduled for Sept. 6. Last year, the Justice Department said it would not seek the death penalty.

Another inmate, Sean McKinnon, pleaded guilty in June to lying to FBI special agents. McKinnon got credit for spending 22 months in custody after his 2022 indictment, was given no additional prison time and was returned to Florida to finish his supervised release. McKinnon had served out a sentence for stealing guns from a firearms dealer.

Plea deals for the three men were disclosed May 13. Geas and DeCologero were identified as suspects shortly after Bulger’s death, but they remained uncharged for years as the investigation dragged on.

Prior to Bulger's death, employees at Hazelton had been sounding the alarm about violence and understaffing. After Bulger was killed, prison officials were criticized for placing him in the general population instead of more protective housing.

A Justice Department inspector general investigation found in 2022 that the killing was the result of multiple layers of management failures, widespread incompetence and flawed policies at the federal Bureau of Prisons. The inspector general found no evidence of “malicious intent” by any bureau employees but said a series of bureaucratic blunders left Bulger at the mercy of rival gangsters.

In July, the U.S. Senate passed legislation to overhaul oversight and bring greater transparency to the Bureau of Prisons following reporting from The Associated Press that exposed systemic corruption in the federal prison system and increased congressional scrutiny.

Bulger, who ran the largely Irish mob in Boston in the 1970s and ’80s, was also an FBI informant who provided the agency with information on the main rival to his gang.

He became one of the nation’s most wanted fugitives after fleeing Boston in 1994, thanks to a tip from his FBI handler that he was about to be indicted. He was captured at age 81 after more than 16 years on the run.

Bulger was convicted in 2013 in a string of 11 killings and dozens of other gangland crimes, many of them committed while he was said to be an FBI informant.

DeCologero, who was in a gang led by his uncle, was convicted of buying heroin that was used to try to kill a teenage girl because his uncle feared she would betray the crew to police. After the heroin did not kill her, another man broke her neck, dismembered her body and buried her remains in the woods, court records say.

Geas was a close associate of the Mafia and acted as an enforcer but was not an official “made” member because he is Greek, not Italian. He and his brother were sentenced to life in 2011 for their roles in several violent crimes, including the 2003 killing of Adolfo “Big Al” Bruno, a Genovese crime family boss in Springfield, Massachusetts. Another mobster ordered Bruno’s killing because he was upset that he had talked to the FBI, prosecutors said.

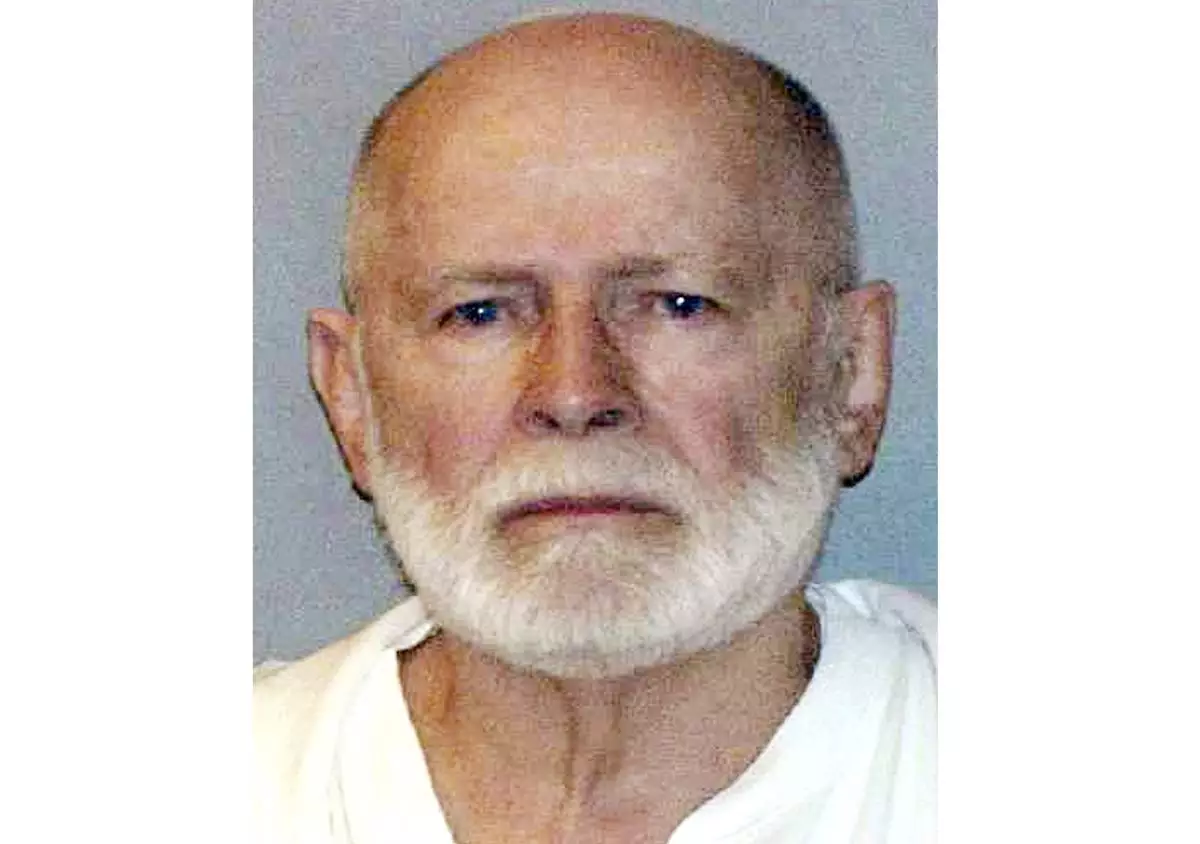

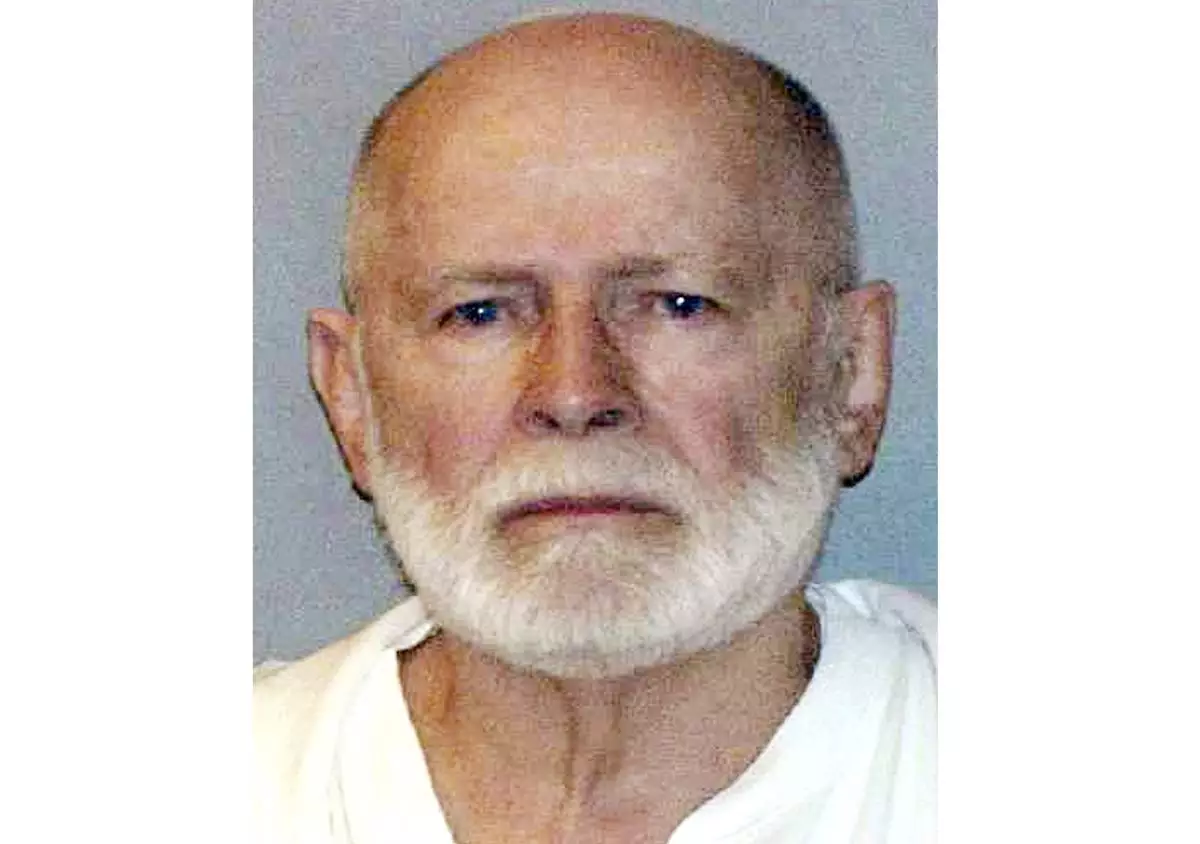

FILE - This June 23, 2011, file booking photo provided by the U.S. Marshals Service shows James "Whitey" Bulger. Bulger was fatally beaten at a West Virginia prison in October 2018. An inmate, Paul J. DeCologero, is due in court Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, for a plea hearing and sentencing on charges in Bulger’s death. (U.S. Marshals Service via AP, File)

FILE - In this June 30, 2011 file photo, James "Whitey" Bulger, right, is escorted from a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter to a waiting vehicle at an airport in Plymouth, Mass., after attending hearings in federal court in Boston. Bulger was fatally beaten at a West Virginia prison in October 2018. An inmate, Paul J. DeCologero, is due in court Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, for a plea hearing and sentencing on charges in Bulger’s death. (Stuart Cahill/The Boston Herald via AP, File)

What's in a name change, after all?

The water bordered by the Southern United States, Mexico and Cuba will be critical to shipping lanes and vacationers whether it’s called the Gulf of Mexico, as it has been for four centuries, or the Gulf of America, as President Donald Trump ordered this week. North America’s highest mountain peak will still loom above Alaska whether it’s called Mt. Denali, as ordered by former President Barack Obama in 2015, or changed back to Mt. McKinley as Trump also decreed.

But Trump's territorial assertions, in line with his “America First” worldview, sparked a round of rethinking by mapmakers and teachers, snark on social media and sarcasm by at least one other world leader. And though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis put the Trumpian “Gulf of America” on an official document and some other gulf-adjacent states were considering doing the same, it was not clear how many others would follow Trump's lead.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum joked that if Trump went ahead with the renaming, her country would rename North America “Mexican America.” On Tuesday, she toned it down: “For us and for the entire world it will continue to be called the Gulf of Mexico.”

Map lines are inherently political. After all, they're representations of the places that are important to human beings — and those priorities can be delicate and contentious, even more so in a globalized world.

There’s no agreed-upon scheme to name boundaries and features across the Earth.

“Denali” is the mountain's preferred name for Alaska Natives, while “McKinley" is a tribute to President William McKinley, designated in the late 19th century by a gold prospector. China sees Taiwan as its own territory, and the countries surrounding what the United States calls the South China Sea have multiple names for the same body of water.

The Persian Gulf has been widely known by that name since the 16th century, although usage of “Gulf” and “Arabian Gulf” is dominant in many countries in the Middle East. The government of Iran — formerly Persia — threatened to sue Google in 2012 over the company’s decision not to label the body of water at all on its maps. Many Arab countries don’t recognize Israel and instead call it Palestine. And in many official releases, Israel calls the occupied West Bank by its biblical name, “Judea and Samaria.”

Americans and Mexicans diverge on what to call another key body of water, the river that forms the border between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. Americans call it the Rio Grande; Mexicans call it the Rio Bravo.

Trump's executive order — titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness” — concludes thusly: “It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes. The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our Nation’s rich past.”

But what to call the gulf with the 3,700-mile coastline?

“It is, I suppose, an internationally recognized sea, but (to be honest), a situation like this has never come up before so I need to confirm the appropriate convention,” said Peter Bellerby, who said he was talking over the issue with the cartographers at his London company, Bellerby & Co. Globemakers. “If, for instance, he wanted to change the Atlantic Ocean to the American Ocean, we would probably just ignore it."

As of Wednesday night, map applications for Google and Apple still called the mountain and the gulf by their old names. Spokespersons for those platforms did not immediately respond to emailed questions.

A spokesperson for National Geographic, one of the most prominent map makers in the U.S., said this week that the company does not comment on individual cases and referred questions to a statement on its web site, which reads in part that it "strives to be apolitical, to consult multiple authoritative sources, and to make independent decisions based on extensive research.” National Geographic also has a policy of including explanatory notes for place names in dispute, citing as an example a body of water between Japan and the Korean peninsula, referred to as the Sea of Japan by the Japanese and the East Sea by Koreans.

In discussion on social media, one thread noted that the Sears Tower in Chicago was renamed the Willis Tower in 2009, though it's still commonly known by its original moniker. Pennsylvania's capital, Harrisburg, renamed its Market Street to Martin Luther King Boulevard and then switched back to Market Street several years later — with loud complaints both times. In 2017, New York's Tappan Zee Bridge was renamed for the late Gov. Mario Cuomo to great controversy. The new name appears on maps, but “no one calls it that,” noted another user.

“Are we going to start teaching this as the name of the body of water?” asked one Reddit poster on Tuesday.

“I guess you can tell students that SOME PEOPLE want to rename this body of water the Gulf of America, but everyone else in the world calls it the Gulf of Mexico,” came one answer. “Cover all your bases — they know the reality-based name, but also the wannabe name as well.”

Wrote another user: “I'll call it the Gulf of America when I'm forced to call the Tappan Zee the Mario Cuomo Bridge, which is to say never.”

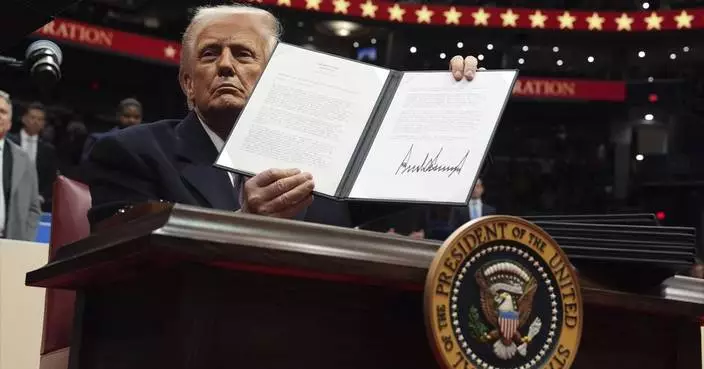

FILE - President Donald Trump speaks in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Peter Bellerby, the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, holds a globe at a studio in London, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - A boat is seen on the Susitna River near Talkeetna, Alaska, on Sunday, June 13, 2021, with Denali in the background. Denali, the tallest mountain on the North American continent, is located about 60 miles northwest of Talkeetna. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen, File)

FILE - The water in the Gulf of Mexico appears bluer than usual off of East Beach, Saturday, June 24, 2023, in Galveston, Texas. (Jill Karnicki/Houston Chronicle via AP, File)