PARIS (AP) — Remco Evenepoel and his Belgian teammates, along with most of the big names in the road race at the Paris Olympics, pedaled softly within a caravan earlier this week as the cyclists did a slow recon ride of the course they will face on Saturday.

The finishing circuit through the bustling tourist area of Montmartre, where the basilica of Sacre Coeur rises high above the city, was supposed to be closed for the ride. But with too many pedestrians and far too much traffic to control, the riders had to be content with a controlled 30 kph (18 mph) look at what could be the decisive spot on the course.

Click to Gallery

Grace Brown, of Australia, centre, shows the gold medal of the women's cycling time trial event, flanked by silver medallist Anna Henderson, of Britain, left, and bronze medallist Chloe Dygert, of United States, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Grace Brown, of Australia, competes in the women's cycling time trial event, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Grace Brown, of Australia, centre, shows the gold medal of the women's cycling time trial event, flanked by silver medallist Anna Henderson, of Britain, left, and bronze medallist Chloe Dygert, of United States, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Remco Evenepoel, of Belgium, left, reacts after winning the men's cycling time trial event, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Remco Evenepoel, of Belgium, wins the men's cycling time trial event, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Netherlands' Mathieu van der Poel reacts after crossing the finish line of the twenty-first stage of the Tour de France cycling race, an individual time trial over 33.7 kilometers (20.9 miles) with start in Monaco and finish in Nice, France, Sunday, July 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Daniel Cole)

The biggest favorite in the men's race decided it wasn't worth it.

Instead, Mathieu van der Poel headed into the countryside for a training ride of his own. He later explained to Dutch newspaper Algemeen Dagblad that it wasn't worth “sacrificing an entire afternoon to cycle around at a tourist pace.”

“I don't find that very useful,” he said. “There are plenty of videos of the course.”

You can bet van der Poel and the rest of the riders will be going decidedly faster than “tourist pace” with medals on the line.

The men's and women's road races traditionally open the cycling program at the Summer Games, but the schedule was altered for Paris. The men and women instead contested a rainy, treacherous time trial last Saturday — Evenepoel survived the slickness to win the men's gold medal, and Grace Brown of Australia took gold in the women's race — before mountain bike, BMX freestyle and BMX racing took center stage at venues scattered around the region.

Now, after a full week of Olympic competition, the focus of cycling shifts back to the road.

The men will ride 273 kilometers (170 miles) on Saturday and the women 158 kilometers (98 miles) on Sunday. Both will depart from the Pont d'Iena, the bridge at the base of the Eiffel Tower crossing the Seine, and head west into the French countryside on identical routes. They diverge there before the men and women contest the same run-in to the finish.

That is what they reconned Thursday, and where both of the races could be decided this weekend.

Riders first pass the Louvre on the way to the finishing circuit at Montmartre, which they will do three times. It includes a steep, kilometer-long climb to the final summit and difficult stretches of cobbles that could throw open the entire race.

"I found the finishing circuit tougher than expected,” said Lorena Wiebes, the leader of a powerful Dutch team that includes Tour de France winner Demi Vollering and former world champions Marianne Vos and Ellen van Dijk. “That last climb at Montmartre is 10 kilometers from the finish, but the peloton will be stretched. It’s all up and down, and a lot of corners.”

It's a course similar to some of the spring one-day Classics such as Paris-Nice, and those tend to favor riders with big power and bike-handling ability — like van der Poel, for example, or any of the riders on the Belgian squad.

Among them is Evenepoel, who followed his third-place finish at the Tour de France by winning the Olympic time trial. He is part of a strong contingent from Belgium that includes time trial bronze medalist Wout van Aert, Jasper Stuyven and Tiesj Benoot.

“Luckily, I’m not the lonely leader in my team, so we have multiple cards to play,” Evenepoel said. “Wout is in very good shape. Jasper as well. Tiesj is also always good in Classics races. We have a very strong team. Unfortunately, there are some other strong riders from other teams as well that are participating.”

The top five nations in the UCI standings get four riders apiece, giving them a big advantage in the smaller Olympic fields.

On the men's side, those teams include France, led by Julian Alaphilippe; the British team of Tom Pidcock, who won a second straight mountain bike gold medal last weekend; the Danish team led by versatile Mads Pedersen; and Slovenia, which Matej Mohoric will lead in place of Tour winner Tadej Pogacar, who withdrew from the Olympics due to fatigue.

The U.S. has three in the men's race, with Matteo Jorgenson joining Brandon McNulty and Magnus Sheffield.

In the women's race, the biggest competition for the Dutch could come from Italy, whose four-rider lineup features Elisa Longo Borghini. Other top teams include the British squad of Lizzie Deignan, the Belgian team of Lotte Kopecky and the Danish bunch of Cecilie Uttrup Ludwig, who hopes to be fully recovered from her crash in the rainy time trial.

Kristen Faulkner will join time trial bronze medalist Chloe Dygert to represent the Americans in the women's road race.

AP Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/2024-paris-olympic-games

Grace Brown, of Australia, competes in the women's cycling time trial event, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Grace Brown, of Australia, centre, shows the gold medal of the women's cycling time trial event, flanked by silver medallist Anna Henderson, of Britain, left, and bronze medallist Chloe Dygert, of United States, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Remco Evenepoel, of Belgium, left, reacts after winning the men's cycling time trial event, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Remco Evenepoel, of Belgium, wins the men's cycling time trial event, at the 2024 Summer Olympics, Saturday, July 27, 2024, in Paris, France. (AP Photo/Ricardo Mazalan)

Netherlands' Mathieu van der Poel reacts after crossing the finish line of the twenty-first stage of the Tour de France cycling race, an individual time trial over 33.7 kilometers (20.9 miles) with start in Monaco and finish in Nice, France, Sunday, July 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Daniel Cole)

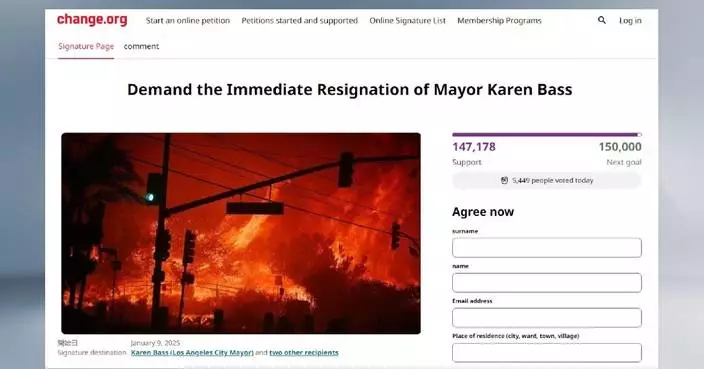

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — As President Donald Trump cracks down on immigrants in the U.S. illegally, some families are wondering if it is safe to send their children to school.

In many districts, educators have sought to reassure immigrant parents that schools are safe places for their kids, despite the president's campaign pledge to carry out mass deportations. But fears intensified for some when the Trump administration announced Tuesday it would allow federal immigration agencies to make arrests at schools, churches and hospitals, ending a decades-old policy.

“Oh, dear God! I can’t imagine why they would do that,” said Carmen, an immigrant from Mexico, after hearing that the Trump administration had rescinded the policy against arrests in “sensitive locations.”

She plans to take her two grandchildren, ages 6 and 4, to their school Wednesday in the San Francisco Bay Area unless she hears from school officials it is not safe.

“What has helped calm my nerves is knowing that the school stands with us and promised to inform us if it’s not safe at school,” said Carmen, who spoke on condition that only her first name be used, out of fear she could be targeted by immigration officials.

Immigrants across the country have been anxious about Trump's pledge to deport millions of people. While fears of raids did not come to pass on the administration's first day, rapid changes on immigration policy have left many confused and uncertain about their future.

At a time when many migrant families — even those in the country legally — are assessing whether and how to go about in public, many school systems are watching for effects on student attendance. Several schools said they were fielding calls from worried parents about rumors that immigration agents would try to enter schools, but it was too early to tell whether large numbers of families are keeping their children home.

Missing school can deprive students of more than learning. For students from low-income families, including many immigrants, schools are a primary way to access food, mental health services and other support.

Tuesday’s move to clear the way for arrests at schools reverses guidance that restricted two federal agencies — Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection — from carrying out enforcement in sensitive locations. In a statement, the Department of Homeland Security said: "Criminals will no longer be able to hide in America’s schools and churches to avoid arrest.”

Daniela Anello, who heads D.C. Bilingual Public Charter School in the nation’s capital, said she was shocked by the announcement.

“It’s horrific,” Anello said. “There’s no such thing as hiding anyone. It doesn’t happen, hasn’t happened. ... It’s ridiculous.”

An estimated 733,000 school-aged children are in the U.S. illegally, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Many more have U.S. citizenship but have parents who are in the country illegally.

Education officials in some states and districts have vowed to stand up for immigrant students, including their right to a public education. In California, for one, officials have offered guidance to schools on state law limiting local participation in immigration enforcement.

A resolution passed by Chicago Public Schools’ Board of Education in November said schools would not assist ICE in enforcing immigration law. Agents would not be allowed into schools without a criminal warrant, it said. And New York City principals last month were reminded by the district of policies including one against collecting information on a student’s immigration status.

That's not the case everywhere. Many districts have not offered any reassurances for immigrant families.

Educators at Georgia Fugees Academy Charter School have learned even students and families in the country legally are intimidated by Trump’s wide-ranging proposals to deport millions of immigrants and roll back non-citizens' rights.

“They’re not even at risk of deportation and they’re still scared,” Chief Operating Officer Luma Mufleh said. Officials at the small Atlanta charter school focused on serving refugees and immigrants expected so many students to miss school the day after Trump took office that educators accelerated the school’s exam schedule so students wouldn’t miss important tests.

Asked on Tuesday for attendance data, school officials did not feel comfortable sharing it. “We don’t want our school to be targeted,“ Mufleh said.

The new policy on immigration enforcement at schools likely will prompt some immigrant parents who fear deportation to keep their children home, even if they face little risk, said Michael Lukens, executive director for the Amica Center for Immigrant Rights. He said he believes it's part of the administration’s goal to make life so untenable that immigrants eventually leave the United States on their own.

For Iris Gonzalez in Boston, schools seem like just about the only safe place for her to go as someone in the country illegally. She’s had children in Boston schools for nearly a decade and she doesn’t expect anyone there to bother her or her daughters for proof they’re here legally. So her children will keep going to school. “Education is important,” she said in Spanish.

Gonzalez, who came to the U.S. from Guatemala illegally 14 years ago, does worry about entering a courthouse or driving, even though she has a license. “What if they stop me?” she wonders.

“I don’t sleep,” she said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty about how to look for work, whether to keep driving and what’s going to change."

Carmen, the Mexican grandmother who now lives in California, said returning home is not an option for her family, which faced threats after her son-in-law was kidnapped two years from their home in Michoacan state, an area overrun with drug trafficking gangs.

Her family arrived two years ago under former President Joe Biden’s program allowing asylum-seekers to enter the U.S. and then apply for permission to stay. Following his inauguration Monday, Trump promptly shut down the CBP One app that processed these and other arrivals and has promised to “end asylum” during his presidency.

Carmen has had several hearings on her asylum request, which has not yet been granted.

“My biggest fear is that we don’t have anywhere to go back to," she said. "It’s about saving our lives. And protecting our children.”

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

A student arrives for school Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in the East Boston neighborhood of Boston. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer)

A student arrives for school Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in the East Boston neighborhood of Boston. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer)

Students arrive for school Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in the East Boston neighborhood of Boston. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer)