TOKYO (AP) — Japan's embattled Prime Minister Fumio Kishida surprised the country Wednesday by announcing that he'll step down when his party picks a new leader next month.

His decision clears the way for his governing Liberal Democratic Party to choose a new standard bearer in its leadership election next month. The winner of that election will replace Kishida as both party chief and prime minister.

Click to Gallery

FILE - South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol speaks during a ceremony to mark the 74th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War in Daegu, South Korea, on June 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, Pool, File)

FILE - Japanese Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa speaks during a news conference with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar after the Quad Ministerial Meeting at the Foreign Ministry's Iikura guesthouse in Tokyo, on July 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama, File)

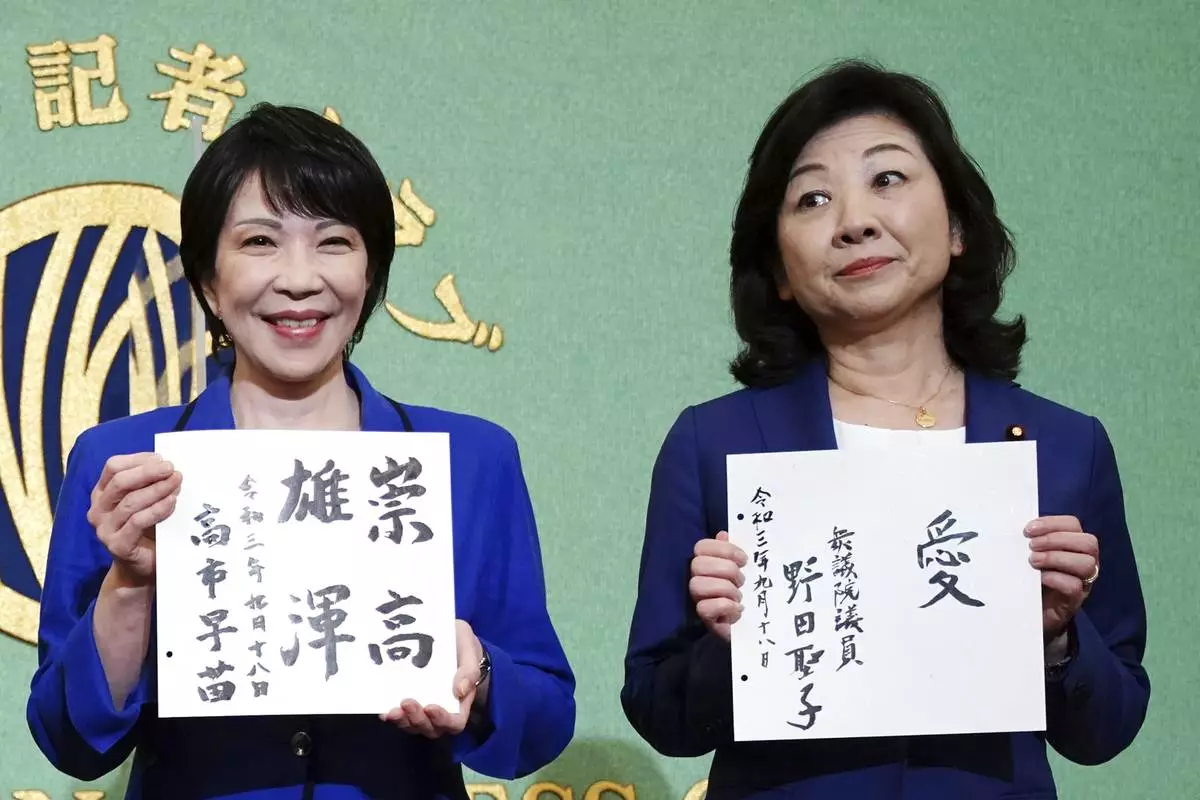

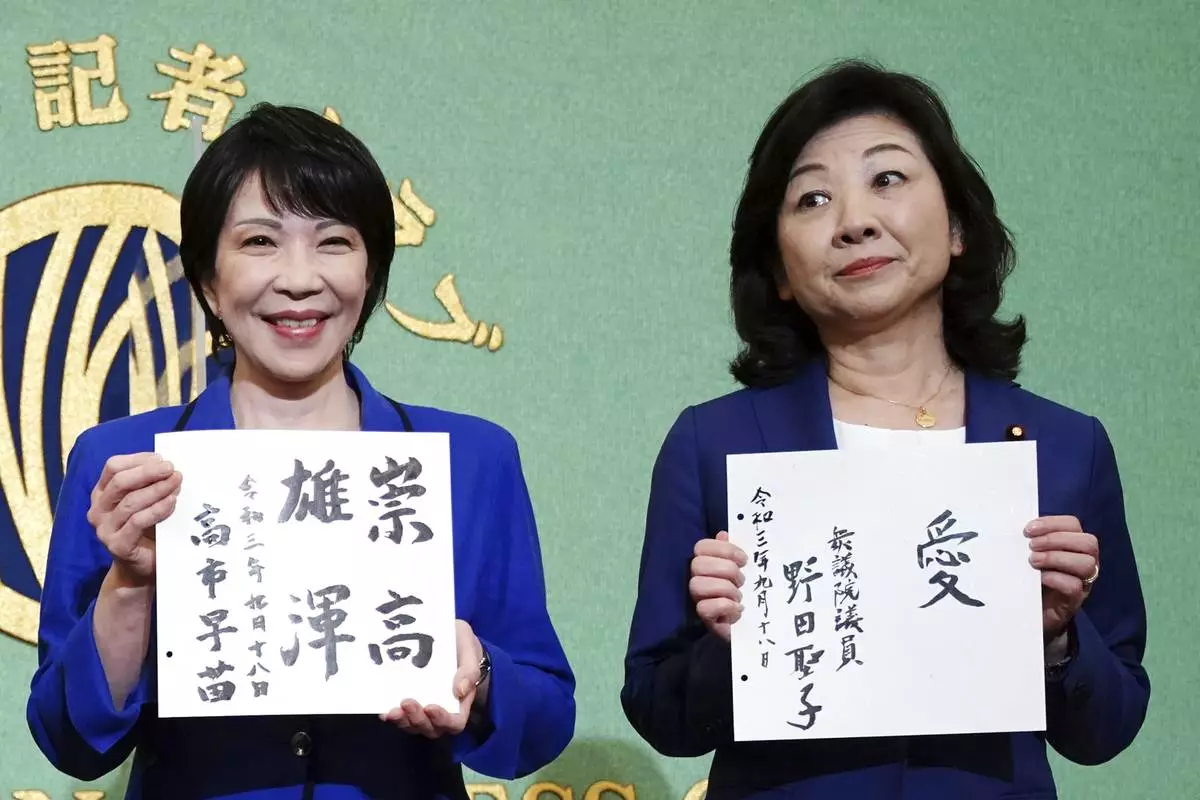

FILE - Sanae Takaichi, left, and Seiko Noda, both former internal affairs ministers and candidates for the presidential election of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, show their motto on cards during a debate session held by Japan National Press club in Tokyo, on Sept. 18, 2021. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko, Pool, File)

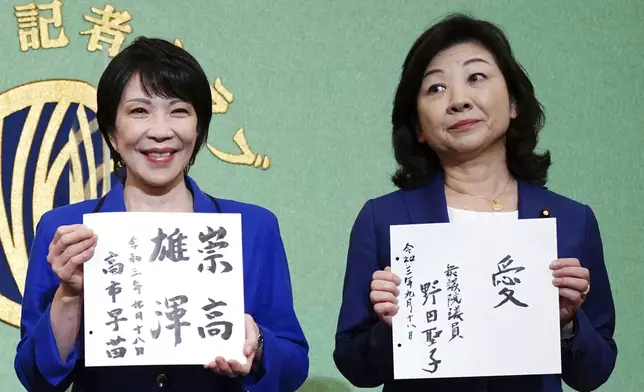

FILE - Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida raises his hand before he speaks about his Liberal Democratic Party's funds scandal during a meeting of the Lower House Budget Committee in Tokyo, on Jan. 29, 2024. (Kyodo News via AP, File)

FILE - The entrance of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, is seen in Tokyo, on Nov. 7, 2023. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama, File)

FIEL - Japan's former Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida poses for a portrait picture following his press conference at the headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party after he was elected as party president in Tokyo, on Sept. 29, 2021. (Du Xiaoyi/Pool Photo via AP, File)

Japan's Prime Minister Fumio Kishida attends a press conference at his office in Tokyo to announce he will not run in the upcoming party leadership vote in September, Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024. (Japan Pool/Kyodo News via AP)

A new leader could help the party shake off scandals that have dogged Kishida's government, and some see a chance for the country to select its first female prime minister.

Here's a look at how the new leader will be chosen, and what it could mean.

Kishida announced plans not to run just days before the LDP is expected to set a date for its triennial leadership vote, which must take place in September.

Kishida will remain party president and prime minister until his successor is elected.

With the LDP in control of both houses of parliament, the next party leader is guaranteed to become prime minister.

Some political watchers say the next general election could come soon after the LDP has a fresh leader, who can choose to hold it at any time before the current term of the lower house ends in October 2025.

A series of local election losses earlier this year sparked calls within his party to have a new face to boost support before the next national election.

Kishida said a series of scandals has “breached” the public’s trust, and the party needs to demonstrate its commitment to change.

He said, “the most obvious first step is for me to bow out.”

The most damaging scandal centered on the failure of dozens of the party's most influential members to report political donations, and resurfaced controversy over the LDP’s decades-old ties with the South Korea-based Unification Church.

Most of Japan's voters won't have a say as the LDP chooses a leader in a vote that's confined to the party's 1.1 million dues-paying members.

They'll vote in a system that divides power between the party's elected lawmakers and its membership at large, with each group getting 50% of the vote.

While LDP leadership votes were long seen as dominated by the party's powerful factional leaders, experts say that's less certain as all but one of the formal factions announced their dissolution in the wake of the party's corruption scandals, in a move led by Kishida.

It's not clear yet who's leading the race to replace Kishida, with speculation focusing on several senior LDP members.

Three of those names belong to women, raising the possibility of a breakthrough in Japan's male-dominated politics.

Experts say the LDP's need to change its image could push it to choose a female prime minister. Only three women have run for the party's leadership in the past, two of whom ran against Kishida in 2021.

Only 10.3% of the members of the lower house of Japan's parliament are women, putting Japan 163rd for female representation among 190 countries examined in a report by the Geneva-based Inter-Parliamentary Union in April.

The LDP's troubles could spill into the general election, but Japan’s fractured opposition may have difficulty capitalizing on the situation.

Experts say voters may want to punish the LDP over its scandals, but don't see opposition parties as viable alternatives.

The main opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan has scored some victories in local elections this year, in part helped by the LDP scandals, but it has struggled to come up with policies that draw contrasts with the governing coalition.

FILE - South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol speaks during a ceremony to mark the 74th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War in Daegu, South Korea, on June 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, Pool, File)

FILE - Japanese Foreign Minister Yoko Kamikawa speaks during a news conference with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar after the Quad Ministerial Meeting at the Foreign Ministry's Iikura guesthouse in Tokyo, on July 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama, File)

FILE - Sanae Takaichi, left, and Seiko Noda, both former internal affairs ministers and candidates for the presidential election of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, show their motto on cards during a debate session held by Japan National Press club in Tokyo, on Sept. 18, 2021. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko, Pool, File)

FILE - Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida raises his hand before he speaks about his Liberal Democratic Party's funds scandal during a meeting of the Lower House Budget Committee in Tokyo, on Jan. 29, 2024. (Kyodo News via AP, File)

FILE - The entrance of the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, is seen in Tokyo, on Nov. 7, 2023. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama, File)

FIEL - Japan's former Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida poses for a portrait picture following his press conference at the headquarters of the Liberal Democratic Party after he was elected as party president in Tokyo, on Sept. 29, 2021. (Du Xiaoyi/Pool Photo via AP, File)

Japan's Prime Minister Fumio Kishida attends a press conference at his office in Tokyo to announce he will not run in the upcoming party leadership vote in September, Wednesday, Aug. 14, 2024. (Japan Pool/Kyodo News via AP)

What's in a name change, after all?

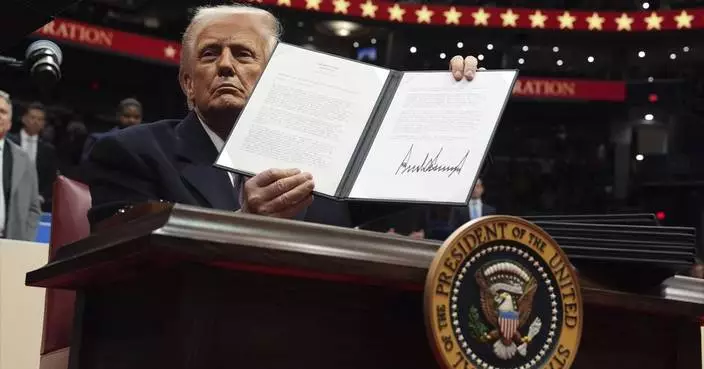

The water bordered by the Southern United States, Mexico and Cuba will be critical to shipping lanes and vacationers whether it’s called the Gulf of Mexico, as it has been for four centuries, or the Gulf of America, as President Donald Trump ordered this week. North America’s highest mountain peak will still loom above Alaska whether it’s called Mt. Denali, as ordered by former President Barack Obama in 2015, or changed back to Mt. McKinley as Trump also decreed.

But Trump's territorial assertions, in line with his “America First” worldview, sparked a round of rethinking by mapmakers and teachers, snark on social media and sarcasm by at least one other world leader. And though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis put the Trumpian “Gulf of America” on an official document and some other gulf-adjacent states were considering doing the same, it was not clear how many others would follow Trump's lead.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum joked that if Trump went ahead with the renaming, her country would rename North America “Mexican America.” On Tuesday, she toned it down: “For us and for the entire world it will continue to be called the Gulf of Mexico.”

Map lines are inherently political. After all, they're representations of the places that are important to human beings — and those priorities can be delicate and contentious, even more so in a globalized world.

There’s no agreed-upon scheme to name boundaries and features across the Earth.

“Denali” is the mountain's preferred name for Alaska Natives, while “McKinley" is a tribute to President William McKinley, designated in the late 19th century by a gold prospector. China sees Taiwan as its own territory, and the countries surrounding what the United States calls the South China Sea have multiple names for the same body of water.

The Persian Gulf has been widely known by that name since the 16th century, although usage of “Gulf” and “Arabian Gulf” is dominant in many countries in the Middle East. The government of Iran — formerly Persia — threatened to sue Google in 2012 over the company’s decision not to label the body of water at all on its maps. Many Arab countries don’t recognize Israel and instead call it Palestine. And in many official releases, Israel calls the occupied West Bank by its biblical name, “Judea and Samaria.”

Americans and Mexicans diverge on what to call another key body of water, the river that forms the border between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. Americans call it the Rio Grande; Mexicans call it the Rio Bravo.

Trump's executive order — titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness” — concludes thusly: “It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes. The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our Nation’s rich past.”

But what to call the gulf with the 3,700-mile coastline?

“It is, I suppose, an internationally recognized sea, but (to be honest), a situation like this has never come up before so I need to confirm the appropriate convention,” said Peter Bellerby, who said he was talking over the issue with the cartographers at his London company, Bellerby & Co. Globemakers. “If, for instance, he wanted to change the Atlantic Ocean to the American Ocean, we would probably just ignore it."

As of Wednesday night, map applications for Google and Apple still called the mountain and the gulf by their old names. Spokespersons for those platforms did not immediately respond to emailed questions.

A spokesperson for National Geographic, one of the most prominent map makers in the U.S., said this week that the company does not comment on individual cases and referred questions to a statement on its web site, which reads in part that it "strives to be apolitical, to consult multiple authoritative sources, and to make independent decisions based on extensive research.” National Geographic also has a policy of including explanatory notes for place names in dispute, citing as an example a body of water between Japan and the Korean peninsula, referred to as the Sea of Japan by the Japanese and the East Sea by Koreans.

In discussion on social media, one thread noted that the Sears Tower in Chicago was renamed the Willis Tower in 2009, though it's still commonly known by its original moniker. Pennsylvania's capital, Harrisburg, renamed its Market Street to Martin Luther King Boulevard and then switched back to Market Street several years later — with loud complaints both times. In 2017, New York's Tappan Zee Bridge was renamed for the late Gov. Mario Cuomo to great controversy. The new name appears on maps, but “no one calls it that,” noted another user.

“Are we going to start teaching this as the name of the body of water?” asked one Reddit poster on Tuesday.

“I guess you can tell students that SOME PEOPLE want to rename this body of water the Gulf of America, but everyone else in the world calls it the Gulf of Mexico,” came one answer. “Cover all your bases — they know the reality-based name, but also the wannabe name as well.”

Wrote another user: “I'll call it the Gulf of America when I'm forced to call the Tappan Zee the Mario Cuomo Bridge, which is to say never.”

FILE - President Donald Trump speaks in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Peter Bellerby, the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, holds a globe at a studio in London, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - A boat is seen on the Susitna River near Talkeetna, Alaska, on Sunday, June 13, 2021, with Denali in the background. Denali, the tallest mountain on the North American continent, is located about 60 miles northwest of Talkeetna. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen, File)

FILE - The water in the Gulf of Mexico appears bluer than usual off of East Beach, Saturday, June 24, 2023, in Galveston, Texas. (Jill Karnicki/Houston Chronicle via AP, File)