MEXICO CITY (AP) — Claudia Santos’ spiritual journey has left a mark on her skin.

Soon after the 50-year-old embraced her pre-Hispanic heritage and pledged to speak for her ancestors’ worldview in Mexico City, she tattooed the symbol “Ollin” — which translates from the Nahuatl language as “movement” — on her wrist.

“It’s an imprint from my Nahuatl name,” said Santos, wearing white with feathers hanging from her neck. She was dressed to perform an ancestral Mexica ceremony on Tuesday in the neighborhood of Tepito.

“It’s an insignia that represents me, my identity.”

Since 2021, when she co-founded an organization that raises awareness of her community’s Mexica heritage, Santos and members of close Indigenous communities gather by mid-August to honor Cuauhtémoc, who was the last emperor or “tlatoani” of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, as the capital was known before it fell to the Spaniards in 1521.

“It’s important to be here, 503 years after what happened, not only to dignify Tepito as an Indigenous neighborhood where there has been resistance, strength and perseverance,” Santos said. “But also because this is an energetic portal, a sacred ‘teocalli’ (‘God’s house’, in Nahuatl).”

The site that she chose for performing the ceremony has a profound sacred meaning in Mexico’s history. Though it’s currently a Catholic church, it’s also the site where Cuauhtémoc — a political and spiritual leader — initiated the final defense of the territory that was lost to the European conquerors.

“Our grandfather, Cuauhtémoc, is still among us,” said Santos, who explained that the site where the church now stands is aligned with the sun. “The cosmic memories of our ancestors are joining us today.”

Though he was not present during the pre-Hispanic rituals, the priest in charge of the Tepito church allowed Santos and fellow Indigenous leaders to move freely through the esplanade of the temple. Their preparations started early each morning, carefully placing roses, fruit, seeds and sculptures of pre-Hispanic figures among other elements.

“I’m very thankful to be given the chance of occupying our sacred compounds once again,” Santos said. “Making this connection between a religious and a spiritual belief is a joy.”

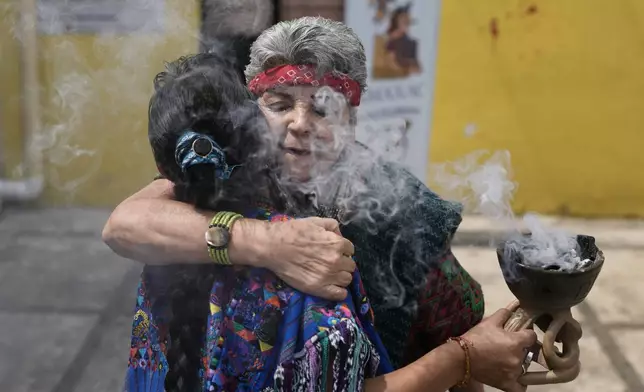

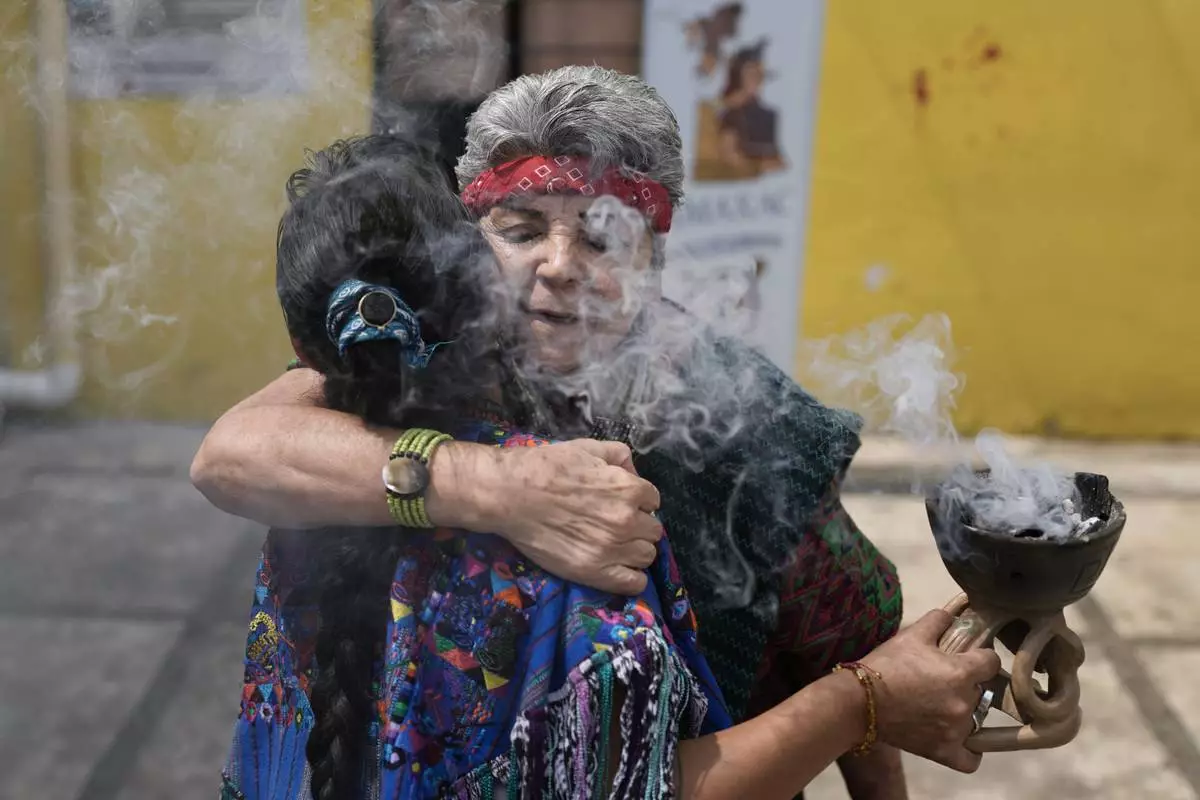

Before Tuesday’s ceremony, as this year’s activities began August 9, a Mayan spiritual guide was also invited to perform a ritual at the church’s main entrance.

“This is an act of kneeling with humbleness, not in humiliation, to make an offering to our Creator,” said Gerardo Luna, the Mayan leader who offered honey, incense, sugar, liquor and other elements as a nourishment for the fire.

“The fire is the element that links us to the spirit of the Creator, who permeates everything that exists,” said Luna, also praising the opportunity to practice his beliefs in a Catholic space.

“There are different ways of understanding spirituality, but there is only one language, the one of the heart,” Luna said. “Our Catholic brothers breathe the same air as us. We all have red blood in our veins, and your bones and mine are the same.”

Some locals approached the church and joined both Mayan and Mexica ceremonies. They were drawn in by the sound of a conch shell that was blown to announce the rituals and the smoke released by the lighting of a resin known as “copal.”

Lucía Moreno, 75, said that participating made her feel at peace. Tomás García, 42, added that he is Catholic, but these ceremonies “purify” him and allow him to let go of any wrongdoing.

Others, like Cleotilde Rodríguez, call upon the ancestors — and God — with a deeper need of comfort.

After Tuesday’s Mexica ritual, the 78-year-old said that she prayed for her health and well-being. No doctor or medicine has cured her aching knees, and none of her 10 children visit her or call to ask how she is. Another son of hers, she said, died by suicide some years ago, and she has not felt at ease since.

“This is what has happened to me, so I hope that God allows me to keep working, that my path is not shortened,” Rodríguez said. “Otherwise, what is going to become of me?”

The “tlalmanalli,” as the Mexica ceremony is known, is as an offering to Mother Earth. All members of the community are encouraged to participate and benefit from its spiritual force.

“What people take with them is medicinal,” Santos said. “It is all blessed, so people leave with medicine for life, which they can use in moments of sadness.”

She was not always aware of the depth of the Mexica and other pre-Hispanic worldviews, but a couple of decades ago, feeling that Catholicism no longer fulfilled her spiritually, she started looking for more.

She researched Buddhism and Hinduism. She practiced yoga and studied the awakening of the mind. But still, she wondered: “What’s in my country? Why, if other nations have gurus, aren’t there any widely known spiritual references in Mexico?”

And then she found them. The Mexica provided her with answers. They were wise, spiritual people, who resisted what others brought upon them, always connected to their ancestors and the profoundness of their land.

As part of her transformation, she received a new name, this time in Nahuatl and tied to the pre-Hispanic calendar. And so, just as her parents baptized her in the very same Tepito church where she now performs Mexica rituals, she embraced her current spirituality in a “sowing” ceremony, where she became “Ollin Chalchiuhtlicue,” which means “precious movement of the water.”

The name, she said, also comes with a purpose. As directed, she defined her life mission after the ceremony. Santos chose to comply with Cuauhtémoc’s final wishes for his people: Maybe the sun has gone down upon us, but it will come out again. In the meantime, we must tell our children — and their children’s children — how big our Motherland’s glory is.

“Through the spirituality of our Mexica tradition we are taking back our dignity and the essence of our Indigenous community,” Santos said. “Being here today is a joy, but also a work of resistance.”

“Tepito exists because it has resisted, and we will continue resisting.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Residents and members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization use incense during a ceremony commemorating the 503 anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Friday, Aug. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Mexica dancers burn incense during a ceremony commemorating the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

People watch as Mexica dancers perform during a ceremony commemorating the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Residents and members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization participate in a ceremony commemorating the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization hold corn during a ceremony commemorating the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Residents and members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization participate in a ceremony commemorating the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Residents and members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization hug during a ceremony commemorating the 503 anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Friday, Aug. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Mexica dancers perform during a ceremony marking the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Residents and members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization hold an statue of a feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, during a ceremony commemorating the 503 anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Friday, Aug. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Mexica dancers perform during a ceremony commemorating the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

Claudia Santos performs a ceremony with residents and members of an Amaxac Indigenous organization to commemorate the 503rd anniversary of the fall of the Aztec empire's capital, Tenochtitlan, in Mexico City, Tuesday, Aug. 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)