FLORHAM PARK, N.J. (AP) — The brief but terrifying feeling of helplessness still gets Wes Schweitzer every time.

The New York Jets offensive lineman is scaling a rock — hand over hand, foot over foot — when he suddenly loses his grip, slips off the wall and plummets a few feet before landing.

“The rope can hold 20,000 pounds, so you’re totally safe, totally fine,” a smiling Schweitzer told The Associated Press after a recent training camp practice. "But every time I fall on the rope, I scream. I’m like, ‘Ahhh!’ You feel like you’re going to die for a second, you know?

“And people look at you funny, but then you realize other people are screaming, too, because it’s just a natural thing. You’re living in the moment and you’re trying not to fall and then you fall, so it’s surprising. So, yes, I still get scared.”

And Schweitzer loves every sometimes-harrowing moment.

Rock climbing has become a passion over the last several years for the 6-foot-4, 325-pounder — an anomaly in a sport in which the participants are predominantly much smaller.

“I’m kind of in uncharted territory,” Schweitzer acknowledged. “I get messages every day about how much I’m inspiring people. And I’m not trying to do this to be like that for others. But it’s really cool that people are looking to me for that because climbing is, well, really hard.”

Schweitzer has taken on indoor rock walls at gyms. He also enjoys bouldering, a form of climbing on small rock formations or artificial rock walls without the use of ropes or harnesses and with pads placed on the ground. The big Arizonan who played at San Jose State has also ventured to some of the most popular outdoor climbs, such as Castle Rock in California, Rocktown in Georgia and the Shawangunk Mountains — aka The Gunks — in New York.

He uses climbing to stay in shape in the offseason for football and regularly posts videos and pictures of his rock-scaling adventures on social media.

“I love it,” Jets offensive line coach Keith Carter said. “I don’t have social media, but I hear about them all the time. Just picturing him climbing up a rock wall is impressive.”

Schweitzer has made the team aware of his passion for climbing — “No one's told me to stop quite yet” — and he stresses safety.

“I think the biggest part of it is they can see my performance on the field,” he said. “And they were like, ‘Oh, if it’s working for him, then keep doing what you’re doing, as long as you don’t get hurt, obviously.’ It’s not any more dangerous than anything else, as long as you’re doing it the right way.”

Schweitzer, who turns 31 next month, hyperextended an elbow early in his NFL career after being drafted in the sixth round by Atlanta in 2016. After traditional rehabilitation for a year never fully healed him, Schweitzer turned to a trainer who recommended he try climbing a rock wall.

“And within five minutes, I was pain free,” Schweitzer recalled. “Something that bothered me for a year.”

So, he kept climbing.

“I gained like 15 pounds of muscle and my play started to get better,” he said. “Now I’ve been doing it for years and years and I’m going outside and I’m doing harder and harder stuff. I’m climbing 200-foot routes and it’s built my confidence up because every day you’re going to get challenged to the maximum.

“This sport of climbing challenges everything that football challenges and also has made me such a better player. I can’t recommend it enough to everybody.”

Schweitzer, who signed a two-year deal with the Jets in March 2023, is a versatile member of New York's offensive line as a backup and spot starter who can play both guard spots and center. And climbing is a prominent part of how he prepares for each season.

“The benefits are through the roof,” Schweitzer said. “The most basic thing is that you grab onto holds and they get harder and harder to hold on to. When I grab shoulder pads now, it’s like I’m holding onto handlebars compared to when I was grabbing on something that was much more difficult to hold on to.

"It’s core strength, but I have to produce power through all my limbs. And then you’re on your toes, so it’s also calves, hips, glutes.”

Schweitzer has talked up climbing to his teammates over the years and taken some out with him.

“But usually they’re exhausted in 10 minutes and they don’t come back,” he said with a laugh.

During the season, Schweitzer sticks to climbing indoor rock walls as a supplement to his regular football workouts.

His goal after football is to someday free climb — using your hands and feet to find handholds and footholds while using a rope tied to a harness — El Capitan, a 3,000-foot tall rock formation in Yosemite National Park in California.

“If you’ve been there and you see that thing, it’s a mile tall and you’re like, this is as cool as it gets,” Schweitzer said. "I’m always an ambitious dreamer, but we’ll see. I just want to push the sport. I want to lose weight to 300 (pounds) and then I want to set benchmarks for, like, no other 300-pound person’s going to be able to do what I’ve done.

“I don’t think anyone’s going to be able to do what I’ve done already, but I want to make it so that it is a firm, like, this is the limit. And then I want to cut as much weight as possible and see what I can do.”

Until then, Schweitzer will keep trying to help the playoff-hungry Jets reach new heights on the football field.

“With teammates, climbing's a talking point,” he said. “I think now at this point in my career, it’s like a selling point. It makes me a little bit different. And I’m proud of it.”

—

AP NFL: https://apnews.com/hub/nfl

FILE- New York Jets offensive guard Wes Schweitzer (71) warms up before an NFL football game against the Atlanta Falcons on Sunday, Dec. 3, 2023, in East Rutherford, N.J. (AP Photo/Bryan Woolston, File)

In this image provided by Shelby Schweitzer, New York Jets offensive lineman Wes Schweitzer climbs Castle Rock in Castle Rock State Park, Calif., in 2021. (Shelby Schweitzer via AP)

In this image provided by Michael Levy, New York Jets offensive lineman Wes Schweitzer takes a break after scaling the Shawangunk Mountains in New York in 2024. (Michael Levy via AP)

What's in a name change, after all?

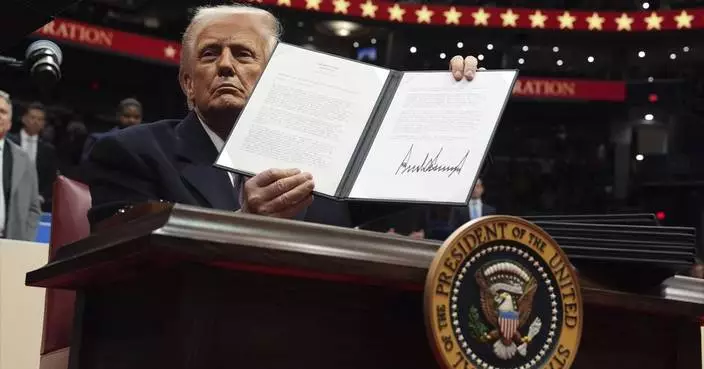

The water bordered by the Southern United States, Mexico and Cuba will be critical to shipping lanes and vacationers whether it’s called the Gulf of Mexico, as it has been for four centuries, or the Gulf of America, as President Donald Trump ordered this week. North America’s highest mountain peak will still loom above Alaska whether it’s called Mt. Denali, as ordered by former President Barack Obama in 2015, or changed back to Mt. McKinley as Trump also decreed.

But Trump's territorial assertions, in line with his “America First” worldview, sparked a round of rethinking by mapmakers and teachers, snark on social media and sarcasm by at least one other world leader. And though Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis put the Trumpian “Gulf of America” on an official document and some other gulf-adjacent states were considering doing the same, it was not clear how many others would follow Trump's lead.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum joked that if Trump went ahead with the renaming, her country would rename North America “Mexican America.” On Tuesday, she toned it down: “For us and for the entire world it will continue to be called the Gulf of Mexico.”

Map lines are inherently political. After all, they're representations of the places that are important to human beings — and those priorities can be delicate and contentious, even more so in a globalized world.

There’s no agreed-upon scheme to name boundaries and features across the Earth.

“Denali” is the mountain's preferred name for Alaska Natives, while “McKinley" is a tribute to President William McKinley, designated in the late 19th century by a gold prospector. China sees Taiwan as its own territory, and the countries surrounding what the United States calls the South China Sea have multiple names for the same body of water.

The Persian Gulf has been widely known by that name since the 16th century, although usage of “Gulf” and “Arabian Gulf” is dominant in many countries in the Middle East. The government of Iran — formerly Persia — threatened to sue Google in 2012 over the company’s decision not to label the body of water at all on its maps. Many Arab countries don’t recognize Israel and instead call it Palestine. And in many official releases, Israel calls the occupied West Bank by its biblical name, “Judea and Samaria.”

Americans and Mexicans diverge on what to call another key body of water, the river that forms the border between Texas and the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas. Americans call it the Rio Grande; Mexicans call it the Rio Bravo.

Trump's executive order — titled “Restoring Names That Honor American Greatness” — concludes thusly: “It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes. The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our Nation’s rich past.”

But what to call the gulf with the 3,700-mile coastline?

“It is, I suppose, an internationally recognized sea, but (to be honest), a situation like this has never come up before so I need to confirm the appropriate convention,” said Peter Bellerby, who said he was talking over the issue with the cartographers at his London company, Bellerby & Co. Globemakers. “If, for instance, he wanted to change the Atlantic Ocean to the American Ocean, we would probably just ignore it."

As of Wednesday night, map applications for Google and Apple still called the mountain and the gulf by their old names. Spokespersons for those platforms did not immediately respond to emailed questions.

A spokesperson for National Geographic, one of the most prominent map makers in the U.S., said this week that the company does not comment on individual cases and referred questions to a statement on its web site, which reads in part that it "strives to be apolitical, to consult multiple authoritative sources, and to make independent decisions based on extensive research.” National Geographic also has a policy of including explanatory notes for place names in dispute, citing as an example a body of water between Japan and the Korean peninsula, referred to as the Sea of Japan by the Japanese and the East Sea by Koreans.

In discussion on social media, one thread noted that the Sears Tower in Chicago was renamed the Willis Tower in 2009, though it's still commonly known by its original moniker. Pennsylvania's capital, Harrisburg, renamed its Market Street to Martin Luther King Boulevard and then switched back to Market Street several years later — with loud complaints both times. In 2017, New York's Tappan Zee Bridge was renamed for the late Gov. Mario Cuomo to great controversy. The new name appears on maps, but “no one calls it that,” noted another user.

“Are we going to start teaching this as the name of the body of water?” asked one Reddit poster on Tuesday.

“I guess you can tell students that SOME PEOPLE want to rename this body of water the Gulf of America, but everyone else in the world calls it the Gulf of Mexico,” came one answer. “Cover all your bases — they know the reality-based name, but also the wannabe name as well.”

Wrote another user: “I'll call it the Gulf of America when I'm forced to call the Tappan Zee the Mario Cuomo Bridge, which is to say never.”

FILE - President Donald Trump speaks in the Roosevelt Room of the White House, Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Peter Bellerby, the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, holds a globe at a studio in London, Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE - A boat is seen on the Susitna River near Talkeetna, Alaska, on Sunday, June 13, 2021, with Denali in the background. Denali, the tallest mountain on the North American continent, is located about 60 miles northwest of Talkeetna. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen, File)

FILE - The water in the Gulf of Mexico appears bluer than usual off of East Beach, Saturday, June 24, 2023, in Galveston, Texas. (Jill Karnicki/Houston Chronicle via AP, File)