Darrell Dixon’s father was just 25 when he had a major heart attack in the rural Mississippi Delta. By his early 40s, a series of additional attacks had left his heart muscle too weak to pump enough blood to his body. He died in 2013 at the age of 49.

“It was a big jolt for our family,” Dixon, 36, recalled. “For myself, personally, it also got me thinking about heredity. I just wondered whether I was next.”

The death spurred Dixon to get involved in an unusual and ambitious new health study.

Public health experts from some of the nation’s leading research institutions have deployed a massive medical trailer to rural parts of the South to test and survey thousands of local residents. The goal: to understand why the rates of heart and lung disease are dramatically higher there than in other parts of the U.S.

“This rural health disadvantage, it doesn’t matter whether you’re white or Black, it hurts you,” said Dr. Vasan Ramachandran, a leader of the project who used to oversee the Framingham Heart Study — the nation's longest-running study of heart disease. “No race is spared, although people of color fare worse.”

The researchers aim to test the heart and lung function of roughly 4,600 residents of 10 counties and parishes in Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi while collecting information about their environments, health history and lifestyles. They are also giving participants a fitness tracker and plan to survey them repeatedly for years to check for any major medical events.

Ramachandran, now dean of the University of Texas School of Public Health in San Antonio, said rural populations in the U.S. rarely receive such personal, long-term attention from epidemiologists. More than a dozen institutions are helping with the study, including Johns Hopkins University, the University of California, Berkeley, and Duke University.

The 52-foot-long (16-meter-long), 27-ton trailer is outfitted with instruments that examine calcium in the arteries, the structure of the heart, lung capacity and other, more common health indicators such as blood pressure and weight. The initial exam can take more than three hours.

“They’re reaching out and going out into the community in ways that I have not seen before,” said Lynn Spruill, the mayor of Starkville, Mississippi, in Oktibbeha County, where the trailer arrived in 2022 and medical staff tested more than 700 people.

Studies and data from U.S. health officials show rural populations in the U.S. are unhealthier and have lower life expectancy than Americans in urban areas. The health disparity is even greater in the South, where mortality rates from heart disease — the leading cause of death in the U.S. — for people 35 and older are more than twice the national average in some rural communities. Lung conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD, which the study is also examining, are also more prevalent in the South.

Researchers have multiple theories for the disparity. Hospital closures and physician shortages have left many rural residents with limited access to care. Healthy food, fitness opportunities and public transit are often scarcer. Poverty rates are higher, and fewer people receive health coverage through their employers. In the rural South, poverty rates and the share of people without health insurance are even greater.

Smoking cigarettes is a major cause of heart disease, and at least 20% of adults smoked in Alabama, Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi, according to 2019 data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity is another factor. In 2022, self-reported height and weight put between 38% and 40% of adults in the four states in the obese body mass index category.

By closely examining local residents and their environments, the rural study seeks clearer answers about what's driving the additional health burden in the South. Researchers also want to understand what makes some rural counties there much healthier than others.

“We’re interested in both the risk, but also the resilience piece of it," said Lindsay Pool, an epidemiologist with the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, which has awarded more than $40 million for the study.

To accomplish that goal, researchers are also visiting rural areas with low risk for heart and lung disease in three of the states — Louisiana, Mississippi and Kentucky — despite similar demographics.

Oktibbeha County, home to Mississippi State University, in the eastern part of Mississippi near the Alabama border, is the low-risk location. The researchers are contrasting it with Panola County in northern Mississippi about 60 miles (97 kilometers) south of Memphis, Tennessee.

Both counties have poverty rates that exceed 20% and a similar and sizeable share of people under 65 without health insurance. But between 2019 and 2021, the death rate from heart disease for those 35 and over was 647 per 100,000 people in Panola County compared to 395 per 100,000 in Oktibbeha County, according to CDC data.

In more urban Rankin County, Mississippi, part of the Jackson metro area, the figure was 331. The U.S. average over the same period was 326.

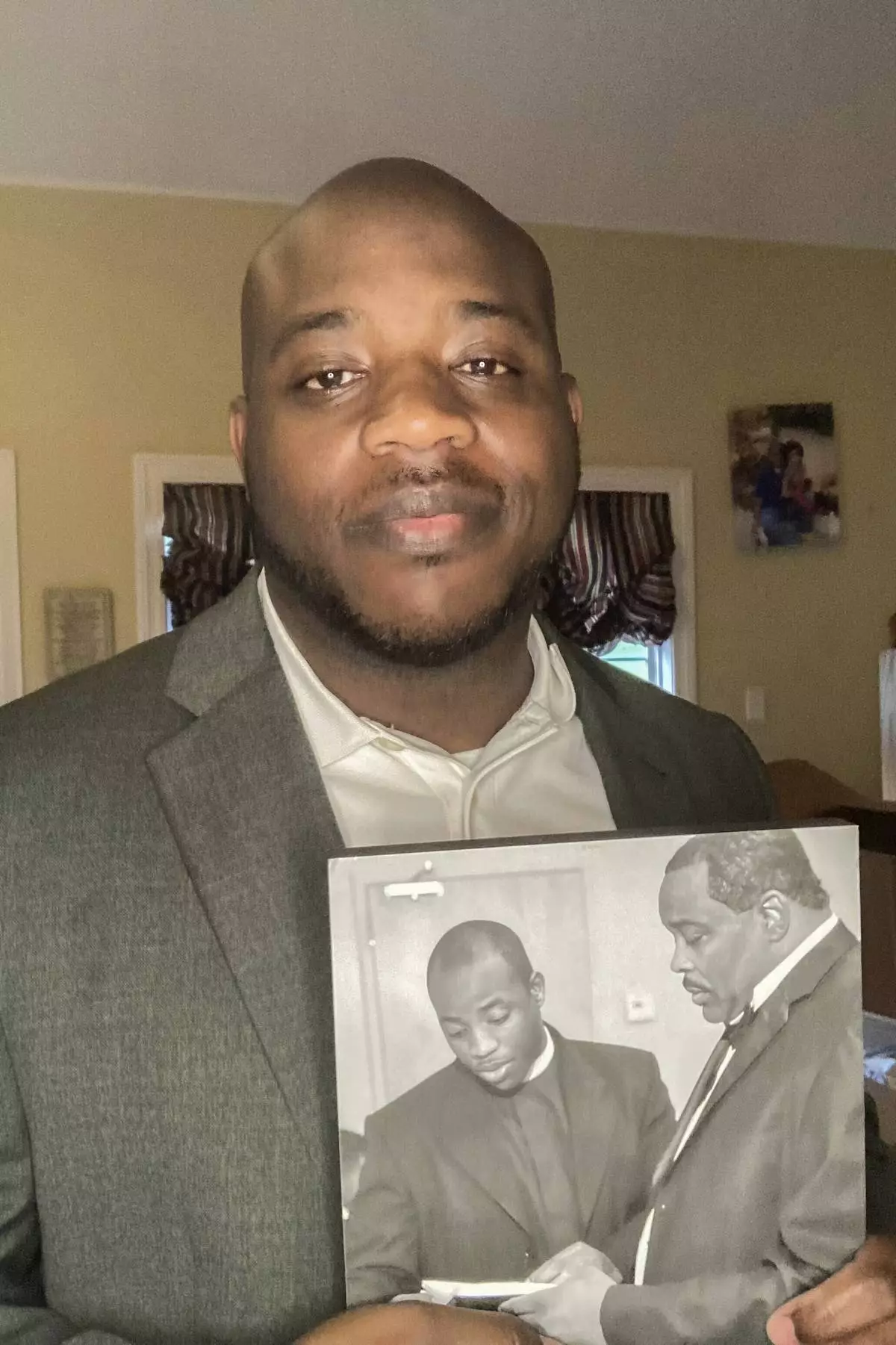

Dixon, who works in Panola County for a regional development organization and serves as a consultant for the heart and lung study, helped recruit more than 600 Panola County residents for the project. Heart conditions are so prevalent there that it's common to hear people discussing their medications and side effects at local shops and churches, he said.

Dixon’s father, Darrell Dixon Sr., lived in Clarksdale, about 40 miles (64 kilometers) west of Panola County. He long suffered from high blood pressure and had a strong family history of heart disease.

He had an additional major heart attack after an inmate he had grown close to as chaplain of the Mississippi State Penitentiary was executed, Dixon said, and then spent the last years of his life in and out of the hospital with congestive heart failure.

“He really suffered,” Dixon said. He hopes the study will shed light on any unseen environmental factors that may have played a role in his dad's death and raise awareness among local residents about “how to live better.”

The trailer is now in Louisiana's northeastern Franklin Parish, where the death rate from heart disease between 2019 and 2021 was a whopping 859 per 100,000 people for those 35 and over, according to the CDC data. About 200 miles (322 kilometers) south in New Orleans, it was 340.

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute plans to extend the study to 2031, and researchers hope to examine all the participants in person again.

“The longer you can follow people, the more you can understand disease development and progression,” Pool, the epidemiologist, said.

A billboard for a new study about why heart and lung disease is so much higher in the rural South is seen in Napoleonville, La., on May 8, 2024. (Sean Coady/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute via AP)

A medical trailer, being used to test rural residents' heart and lung function as part of a study to determine why the rates of heart and lung disease are so much higher in the rural South, is seen, May 8, 2024, in Napoleonville, La. (Sean Coady/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute via AP)

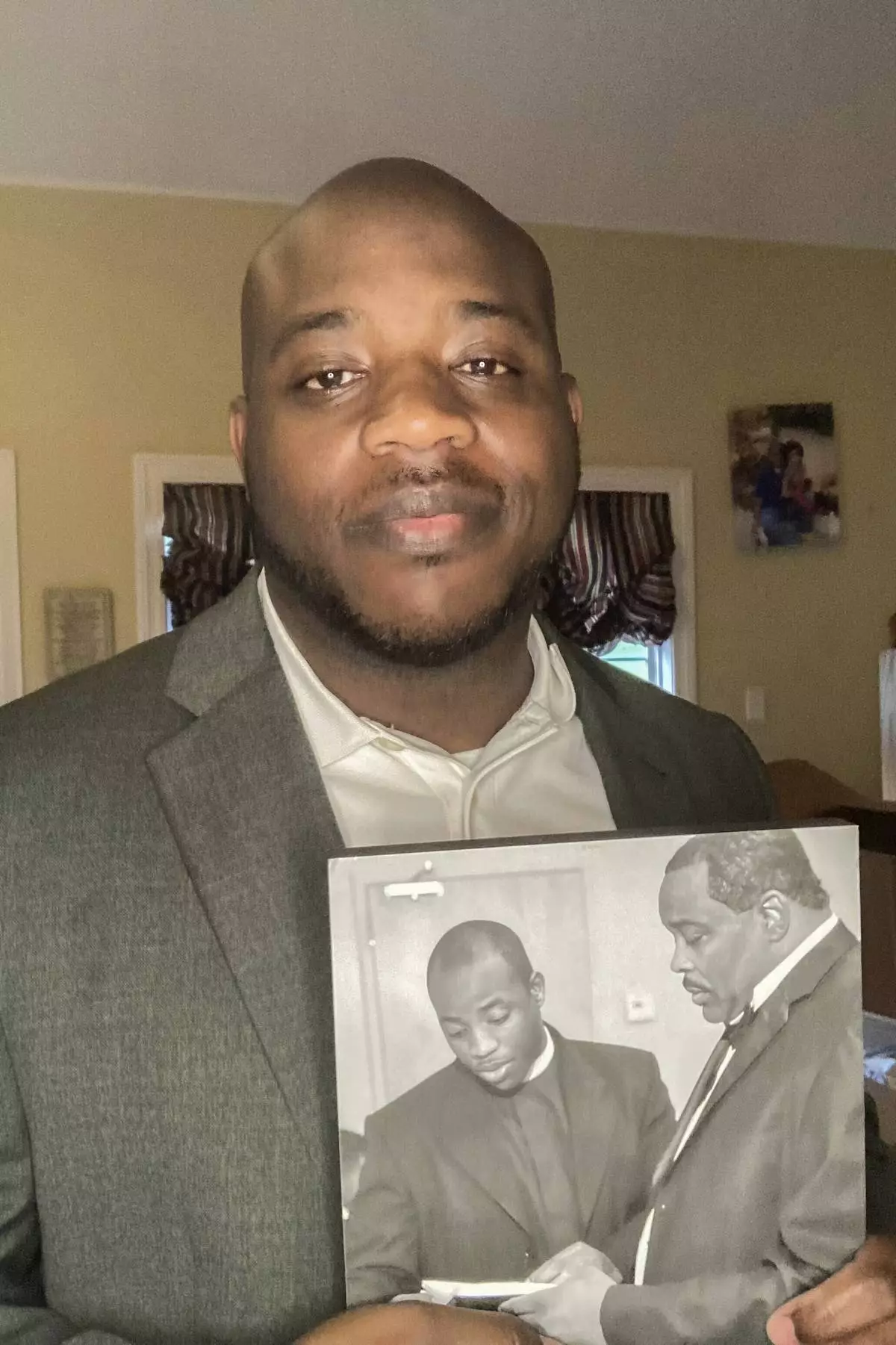

Darrell Dixon holds a photo of him and his dad, Darrell Dixon Sr., at his home in Hernando, Miss., on August 11, 2024. (Millicent Dixon via AP)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — South Korean law enforcement authorities are pushing to summon impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol for questioning over his short-lived martial law decree as the Constitutional Court began its first meeting Monday on Yoon’s case to determine whether to remove him from office or reinstate him.

A joint investigative team involving police, an anti-corruption agency and the Defense Ministry said it wants to question Yoon on charges of rebellion and abuse of power in connection with his ill-conceived power grab.

The team on Monday morning tried to convey a request to Yoon’s office that he appear for questioning on Wednesday but was rerouted to Yoon’s personal residence, Son Yeong-jo, an investigator with the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials, told reporters.

Son cited presidential secretarial staff as claiming they were unsure whether conveying the request to the impeached president was part of their duties. He declined to provide specifics when asked how investigators would respond if Yoon refuses to appear.

Yoon was impeached by the opposition-controlled National Assembly on Saturday over his Dec. 3 martial law decree. His presidential powers have been subsequently suspended, and the Constitutional Court is to determine whether to formally remove him from office or reinstate him. If Yoon is dismissed, a national election to choose his successor must be held within 60 days.

Yoon has justified his martial law enforcement as a necessary act of governance against the main liberal opposition Democratic Party that he described as “anti-state forces” bogging down his agendas and vowed to “fight to the end” against efforts to remove him from office.

Hundreds of thousands of protesters have poured onto the streets of the country’s capital, Seoul, in recent days, calling for Yoon’s ouster and arrest.

It remains unclear whether Yoon will grant the request by investigators for an interview. South Korean prosecutors, who are pushing a separate investigation into the incident, also reportedly asked Yoon to appear at a prosecution office for questioning on Sunday but he refused to do so. Repeated calls to a prosecutors’ office in Seoul were unanswered.

Yoon’s presidential security service has also resisted a police attempt to search Yoon's office for evidence.

Also Monday, the Constitutional Court met for the first time to discuss the case. The court has up to 180 days to rule. But observers say a ruling could come faster.

In the case of parliamentary impeachments of past presidents — Roh Moo-hyun in 2004 and Park Geun-hye in 2016 — the court spent 63 days and 91 days respectively before determining to reinstate Roh and dismiss Park.

Kim Hyungdu, a court justice, told reporters earlier Monday that the court will “swiftly and fairly” make a decision in the case. He said Monday’s court meeting was meant to discuss preparatory procedures and how to arrange arguments at formal trials.

Upholding Yoon’s impeachments needs support from at least six out of the court’s nine justices, but three seats are vacant now. This means a unanimous ruling by the court’s current six justices in favor of Yoon's impeachment is required to formally end his presidency. Kim said he expected the three vacant seats to be filled by the end of this month.

Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, who became the country’s acting leader after Yoon's impeachment, and other government officials have sought to reassure allies and markets after Yoon’s surprise stunt paralyzed politics, halted high-level diplomacy and complicated efforts to revive a faltering economy.

Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung urged the Constitutional Court to rule swiftly on Yoon’s impeachment and proposed a special council for policy cooperation between the government and parliament. Yoon’s conservative People Power Party criticized Lee’s proposal for the special council, saying that it’s “not right” for the opposition party to act like the ruling party.

Lee, a firebrand lawmaker who drove a political offensive against Yoon’s government, is seen as the frontrunner to replace him. He lost the 2022 presidential election to Yoon by a razor-thin margin.

Yoon’s impeachment, which was endorsed in parliament by some of his ruling party lawmakers, has created a deep rift within the party between Yoon’s loyalists and his opponents. On Monday, PPP chair Han Dong-hun, a strong critic of Yoon's martial law, announced his resignation.

“If martial law had not been lifted that night, a bloody incident could have erupted that morning between the citizens who would have taken to the streets and our young soldiers,” Han told a news conference.

Yoon’s Dec. 3 imposition of martial law, the first of its kind in more than four decades, harkened back to an era of authoritarian leaders the country has not seen since the 1980s. Yoon was forced to lift his decree hours later after parliament unanimously voted to overturn it.

Yoon sent hundreds of troops and police officers to the parliament in an effort to stop the vote, but they withdrew after the parliament rejected Yoon’s decree. No major violence occurred.

Opposition parties have accused Yoon of rebellion, saying a president in South Korea is allowed to declare martial law only during wartime or similar emergencies and would have no right to suspend parliament’s operations even in those cases.

South Korea's ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hun speaks during a news conference to announce his resignation after President Yoon Suk Yeol's parliamentary impeachment, at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hun speaks during a news conference to announce his resignation after President Yoon Suk Yeol's parliamentary impeachment, at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's ruling People Power Party leader Han Dong-hun reacts during a news conference to announce his resignation after President Yoon Suk Yeol's parliamentary impeachment, at the National Assembly in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Dec. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Participants shout slogans during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Participants shout slogans during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol, in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Participants shout slogans during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol, in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

In this photo released by South Korean President Office via Yonhap, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol bows while delivering a speech at the presidential residence in Seoul, South Korea, after South Korea’s parliament voted to impeach Yoon Saturday, Dec. 14, 2024. (South Korean Presidential Office/Yonhap via AP)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung speaks during a press conference on removal of President Yoon Suk Yeol from office, at the party office at the National Assembly building in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Participants hold signs during a rally calling on the Constitutional Court to dismiss the President Yoon Suk Yeol in Seoul, South Korea, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2024. The signs read "Immediately arrest." (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)