ATLANTA (AP) — Every Monday evening, the Andrew and Walter Young Family YMCA basement becomes a sanctuary for men who, local leaders say, have too often been denied one.

The Black Man Lab, which for nearly a decade has sought weekly to create a “safe, sacred and healing space” for Black men in metropolitan Atlanta, regularly gathers more than 100 men to pray, meditate and talk through challenges and triumphs they are facing and learn from peers and elders.

Click to Gallery

ATLANTA (AP) — Every Monday evening, the Andrew and Walter Young Family YMCA basement becomes a sanctuary for men who, local leaders say, have too often been denied one.

Panelists answer questions during a panel discussion on the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris during a Black Men Lab meeting, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

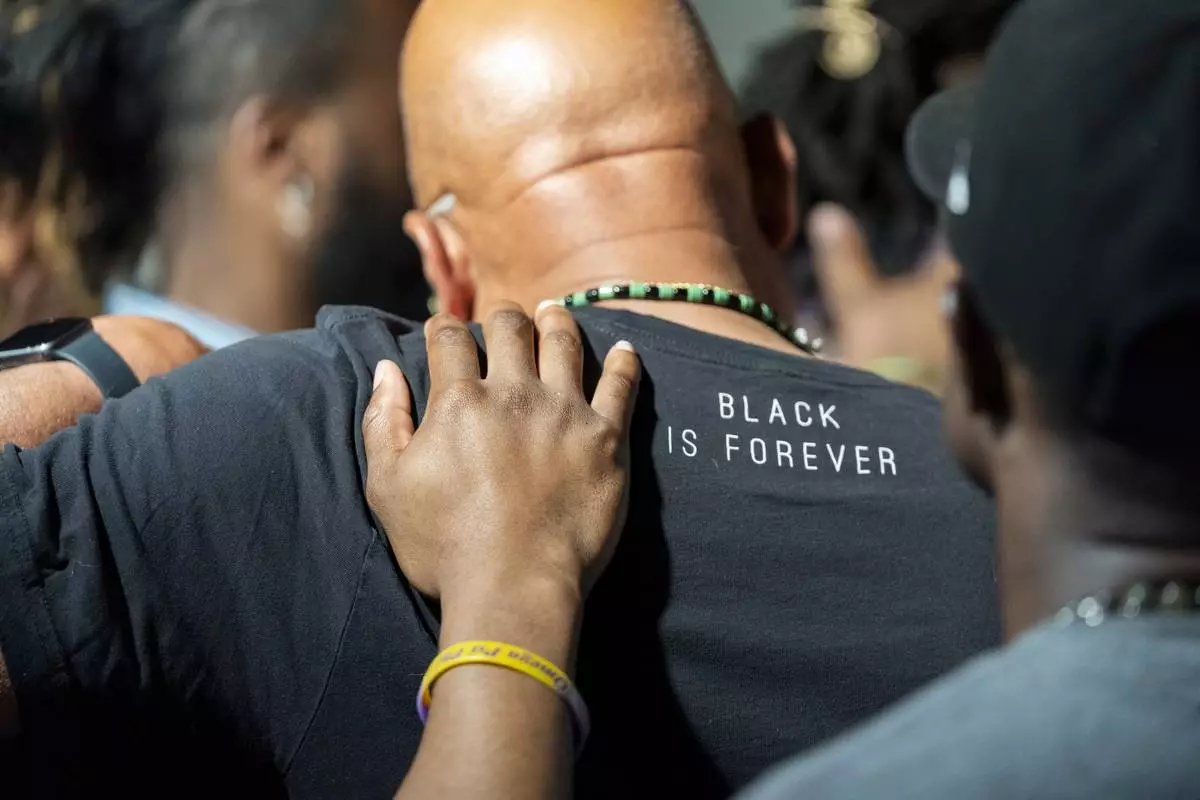

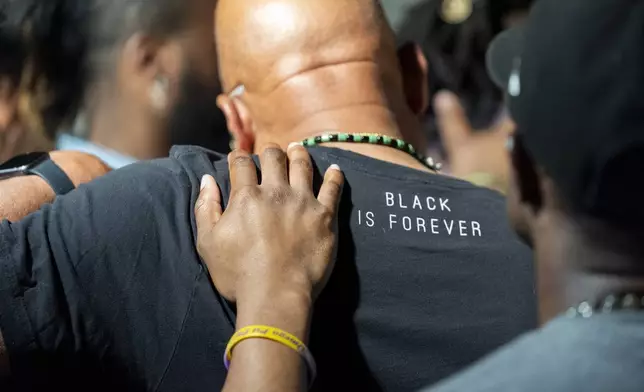

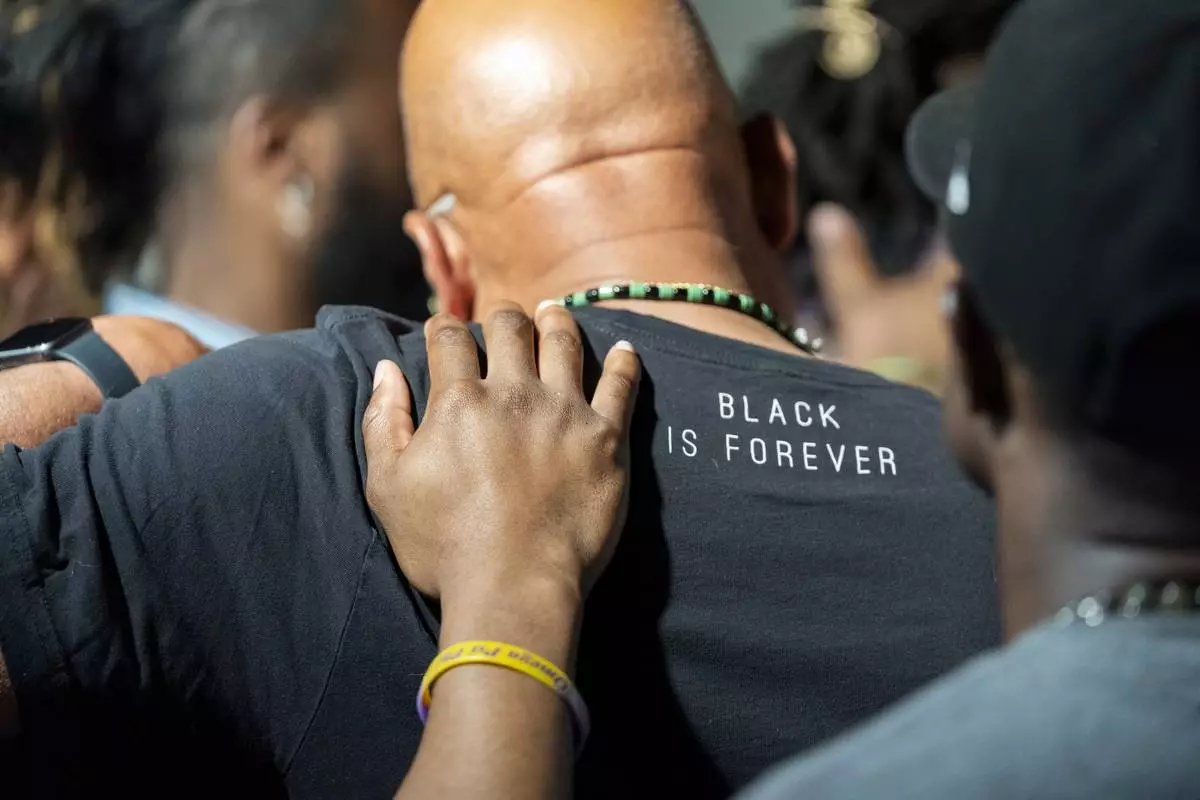

Attendees gather and pray during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Attendees gather and pray during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Cliff Albright of the Black Voters Matter Fund, a nonprofit voting rights organization, speaks during a panel discussion on the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris during a Black Men Lab meeting, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Mawuli Davis, an attorney and human rights organizer, facilitates a panel discussion on the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris during a Black Men Lab meeting, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Panelists and attendees raise their fists during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. The Black Man Lab hosts weekly gatherings with the purpose of providing an intergenerational safe space for Black men and boys. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Panelists and attendees raise their fists during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

“It’s almost a communion,” said Carttrell Coleman, a visual artist from South Fulton, Georgia, who has attended the weekly meetings for seven years. “It’s an opportunity for us to share our voices and get resources. The networking is always a good thing. It’s a fellowship, of sorts.”

One recent meeting in the immediate aftermath of President Joe Biden’s suspension of his reelection campaign took on special weight as attendees considered the prospect of a Black woman winning the presidency. The candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris has refocused attention on Black men, a demographic that Democrats and Republicans view as persuadable but whose multifaceted experiences and political preferences often go unaddressed in public debate.

Harris’ campaign has also reignited discussions amongst Black men about their influence in this election.

“Black men are the target, and we hold the keys to the kingdom. This is our moment,” said Lance Robertson, executive director of the Black City Councilmen of Georgia, during the meeting. “The Black man has built America. Now it’s time for the Black man to save America.”

Black male voters are traditionally one of the most consistently Democratic leaning demographics in the nation. This year, however, both major parties view Black men, especially those under the age of 40, as attainable voters. Whether Black men turn out in high numbers and to what degree they maintain traditional support for Democratic candidates may prove decisive in November.

“To be frank, I think early on in this process a lot of Black men viewed this election with much skepticism and dread,” said Bishop Reginald Jackson, who presides over all 534 African Methodist Episcopal churches in Georgia. “But since the change in the Democratic ticket, there has been a turnaround. I think they feel they have something that they can support. I think a lot of issues which made a lot of them skeptical are being addressed.”

At the Black Man Lab event, the men present came from all walks of life. Attendees' ages ranged from 8 to 86, with multiple pairings of fathers, grandfathers and grandsons telling the group about the unique circumstances each generation faces as Black men in America.

Black voters have historically prioritized policies on civil rights and economic mobility, leading to overwhelming support for Democrats.

But how those concerns translate into political preferences has shifted as traditional ties to institutions like the Black church have frayed for some younger Black Americans. “The Black church, in a lot of respects, has been a turnoff for the Black man, and we’re only now working to address the need and correct it,” Jackson said.

For many younger Black men, advocates stressed, issues like wealth creation, entrepreneurship, police reform and anti-discrimination policies in the workplace are top of mind.

“We want to see jobs and opportunity for Black men, especially,” said Andre Greenwood, chair of the YMCA that hosts the Black Man Lab event. Greenwood, who supports Harris, said economic messages will be most important to Black male voters.

Harris' entrance into the presidential race has unleashed a flurry of organizing among her Black male allies. A day after Biden dropped out of the race and endorsed Harris, a virtual conference tailored for Black men garnered more than 53,000 attendees and raised more than $1.3 million. The event, organized by Win With Black Men, a collective of Black male-led groups, has hosted regular meetings every week since then to engage organizers targeting Black men.

“Up until this point, these folks were not really engaged with this campaign season, let alone volunteering for outside organizations. I think what we’re seeing now is a massive level of organic energy that you can't deny,” said Quentin James, founder of the Collective PAC, a Democratic political action committee that supports Black candidates.

Win With Black Men said it would direct the raised funds to organizations nationwide for Black male engagement. More than 150 groups have applied for support. James stressed that while the recent fundraising windfall is notable, the Harris campaign's own engagement effort with Black men may not be enough unless it is paired with robustly funded outside groups that have longstanding trust in local communities.

Harris has also revamped her outreach to Black men. The campaign believes it has a winning message for Black men's priorities.

“It’s wealth and it’s health,” Democratic strategist Antjuan Seawright said of the message.

Seawright leads the Democratic National Committee's “Chop It Up” town halls for Black men at barbershops and other venues in battleground states this year. He noted that Black men “aren’t monolithic” and added that it is a mistake for campaigns to assume “we only care about criminal justice reform.”

The culminating effort also aims to address longstanding skepticism among many Black men about the political system, which is seen as discriminatory and unresponsive to their interests. Others have tackled potential hesitancy among men about electing a woman to the nation’s highest office.

Republicans, too, see an opportunity to make inroads with Black men precisely because of those longstanding frustrations. Donald Trump often speaks of his interest in garnering greater Black voter support. Black Republicans, including Reps. Byron Donalds of Florida and Wesley Hunt of Texas, have hosted a “Congress, Cognac, and Cigars” event series in cities including Atlanta, Philadelphia and Milwaukee.

“Black men have been taken for granted by the Democratic Party for years, but President Trump’s message is resonating at historic levels because he is doing the work," said Janiyah Thomas, Black media director for the Trump campaign.

Marcus Robinson, a senior spokesperson for the Democratic National Committee, called Republican outreach strategy “hot air, racially charged rhetoric and offensive stereotypes, from questioning Vice President Harris’s identity to claiming Black voters should relate to Trump because he is a convicted felon.”

For many attendees at the Black Man Lab event, the reinvigorated presidential race is an opportunity to make sure their interests are addressed at the highest levels of government.

“I was in the street doing wild stuff and this saved my life,” said Damon Bod, an exterior house technician from Atlanta, of his experience with the Black Man Lab event. Bod said he lost his entire immediate family to violence and that the event provided him counsel and a community.

He said he would support Harris in the election because the men who supported him felt she would advance Black men's interests.

“I've been looking at it and hopefully she'll do a bit of good. My brothers have said she will, people who know me. But only God knows,” Bod said.

The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

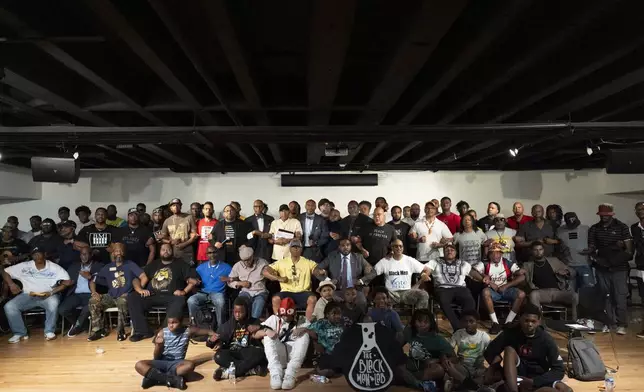

Attendees pose for photos after a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Panelists answer questions during a panel discussion on the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris during a Black Men Lab meeting, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Attendees gather and pray during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Attendees gather and pray during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Cliff Albright of the Black Voters Matter Fund, a nonprofit voting rights organization, speaks during a panel discussion on the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris during a Black Men Lab meeting, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Mawuli Davis, an attorney and human rights organizer, facilitates a panel discussion on the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris during a Black Men Lab meeting, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Panelists and attendees raise their fists during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. The Black Man Lab hosts weekly gatherings with the purpose of providing an intergenerational safe space for Black men and boys. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Panelists and attendees raise their fists during a Black Man Lab meeting to discuss the candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

LIMA, Peru (AP) — Alberto Fujimori, whose decade-long presidency began with triumphs righting Peru’s economy and defeating a brutal insurgency only to end in a disgrace of autocratic excess that later sent him to prison, has died. He was 86.

His death Wednesday in the capital, Lima, was announced by his daughter Keiko Fujimori in a post on X.

He had been pardoned in December from his convictions for corruption and responsibility for the murder of 25 people. His daughter said in July that he was planning to run for Peru’s presidency for the fourth time in 2026.

Fujimori, who governed with an increasingly authoritarian hand in 1990-2000, was pardoned in December from his convictions for corruption and responsibility for the murder of 25 people. His daughter said in July that he was planning to run for Peru’s presidency for the fourth time in 2026.

The former university president and mathematics professor was the consummate political outsider when he emerged from obscurity to win Peru’s 1990 election over writer Mario Vargas Llosa. Over a tumultuous political career, he repeatedly made risky, go-for-broke decisions that alternately earned him adoration and reproach.

He took over a country ravaged by runaway inflation and guerrilla violence, mending the economy with bold actions including mass privatizations of state industries. Defeating fanatical Shining Path rebels took a little longer but also won him broad-based support.

His presidency, however, collapsed just as dramatically.

After briefly shutting down Congress and elbowing himself into a controversial third term, he fled the country in disgrace in 2000 when leaked videotapes showed his spy chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, bribing lawmakers. The president went to Japan, the land of his parents, and famously faxed in his resignation.

He stunned supporters and foes alike five years later when he landed in neighboring Chile, where he was arrested and then extradited to Peru. He had hoped to run for Peru’s presidency in 2006, but instead wound up in court facing charges of abuse of power.

The high-stakes political gambler would lose miserably. He became the first former president in the world to be tried and convicted in his own country for human rights violations. He was not found to have personally ordered the 25 death-squad killings for which he was convicted, but he was deemed responsible because the crimes were committed in his government’s name.

His 25-year sentence did not stop Fujimori from seeking political revindication, which he planned from a prison built in a police academy on the outskirts of Lima, the capital.

His congresswoman daughter Keiko tried in 2011 to restore the family dynasty by running for the presidency but was narrowly defeated in a runoff. She ran again in 2016 and 2021, when she lost by just 44,000 votes after a campaign in which she promised to free her father.

Fujimori told The Associated Press in 2000, seven months before his fall from power, that he viewed political rivals as chess pieces to be outmaneuvered with cool detachment.

“In Latin America, I am a special case,” he said. “I have had a special formation within an Oriental environment of discipline and perseverance.”

Fujimori’s presidency was, in fact, a brash display of outright authoritarianism, known locally as “caudillismo,” in a region shakily stepping away from dictatorships toward democracy.

He is survived by his four children. The oldest, Keiko, became first lady in 1996 when his father divorced his mother, Susana Higuchi, in a bitter battle in which she accused Fujimori of having her tortured. The youngest child, Kenji, was elected a congressman.

Fujimori was born July 28, 1938, Peruvian Independence Day, and his immigrant parents picked cotton until they could open a tailor’s shop in downtown Lima.

He earned a degree in agricultural engineering in 1956, and then studied in France and the United States, where he received a graduate degree in mathematics from the University of Wisconsin in 1972.

In 1984 he became rector of the Agricultural University in Lima, and six years later, he ran for president without ever having held political office, billing himself as a clean alternative to Peru’s corrupt, discredited political class.

He played on the Peruvian stereotype of the honest, hard-working Asian, and raised hopes in an economically distressed nation by arguing that he would attract Japanese aid and technology.

He soared from 6 percent in the polls a month before the 1990 election to finish second out of nine in the balloting. He went on to beat Vargas Llosa in a runoff.

The victory, he later said, came from the same frustration that fueled the Shining Path.

“My government is the product of rejection, of being fed up with Peru because of the frivolity, corruption and nonfunctioning of the traditional political class and the bureaucracy,” he said.

Once in office, Fujimori’s tough talk and hands-on style at first won him only plaudits, as car bombings still ripped through the capital and annual inflation approached 8,000 percent.

He applied the same economic shock therapy that Vargas Llosa had advocated but he had argued against in the campaign.

Privatizing state-owned industries, Fujimori slashed public spending and attracted record foreign investment.

Known affectionately as “El chino,” due to his Asian ancestry, Fujimori often donned peasant garb to visit jungle Indigenous communities and highland farmers, while delivering electricity and drinking water to dirt-poor villages. That distinguished him from the patrician, white politicians who typically lacked his commoner’s touch.

Fujimori also gave Peru’s security forces free rein to take on the Shining Path.

In September 1992, police captured rebel leader Abimael Guzmán. Deservedly or not, Fujimori took credit.

Perhaps his most famous calculation came in April 1997 when he sent U.S.-trained commandos into the Japanese ambassador’s residence where 14 leftist Tupac Amaru rebels had held 72 hostages for months.

Only one hostage was killed. All the hostage-takers, however, were killed, allegedly on Montesinos’ orders.

Taking power just years after much of the region had shed dictatorships, the former university professor ultimately represented a step back. He developed growing a taste for power and resorted to increasingly anti-democratic means to amass more of it.

In April 1992, he shut down Congress and the courts, accusing them of shackling his efforts to defeat the Shining Path and spur economic reforms.

International pressure forced him to call elections for an assembly to replace the Congress. The new legislative body, dominated by his supporters, changed Peru’s constitution to allow the president to serve two consecutive five-year terms. Fujimori was swept back into office in 1995, after a brief border war with Ecuador, in an election landslide.

Human rights advocates at home and abroad blasted him for pushing through a general amnesty law forgiving human rights abuses committed by security forces during Peru’s “anti-subversive” campaign between 1980 and 1995.

The conflict would claim nearly 70,000 lives, a truth commission found, with the military responsible for more than a third of the deaths. Journalists and businessmen were kidnapped, students disappeared and at least 2,000 highland peasant women were forcibly sterilized.

In 1996, Fujimori’s majority bloc in Congress put him on the path for a third term when it approved a law that determined his first five years as president didn’t count because the new constitution was not yet in place when he was elected.

A year later, Fujimori’s Congress fired three Constitutional Tribunal judges who tried to overturn the legislation, and his foes accused him of imposing a democratically elected dictatorship.

By then, almost daily revelations were showing the monumental scale of corruption around Fujimori. About 1,500 people connected to his government were prosecuted on corruption and other charges, including eight former Cabinet ministers, three former military commanders, an attorney general and a former chief of the Supreme Court.

The accusations against Fujimori led to years of legal wrangling. In December, Peru’s Constitutional Court ruled in favor of a humanitarian pardon granted to Fujimori on Christmas Eve in 2017 by then-President Pablo Kuczynski. Wearing a face mask and getting supplemental oxygen, Fujimori walked out of the prison door and got in a sport utility vehicle driven by his daughter-in-law.

The last time he was seen in public was on Sept. 4, leaving a private hospital in a wheelchair. He told the press that he had undergone a CT scan and when asked if his presidential candidacy was still going ahead, he smiled and said “We’ll see, we’ll see.”

Frank Bajak, the principal writer of this obituary, retired from The Associated Press in 2024. Associated Press writer Regina Garcia Cano in Mexico City contributed.

FILE - Former Peru's President Alberto Fujimori waves at his home in Santiago after leaving the academy for the training of corrections officers in Santiago, Chile, May 18, 2006. (AP Photo/Claudio Santana, File)

FILE - Peru's former President Alberto Fujimori is seen gesturing on a screen during the first day of his trial on charges of alleged human rights violations and corruption during his government at a police base in Lima, Dec. 10, 2007. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia, File)