When is a doping scandal not a doping scandal? What about when the accused person is not Chinese?

In the second week of the Olympics, coming up, we will see the UK represented in Taekwando by Jade Jones, a two-time gold medalist looking for her third.

A little digging unearths a report about her. At dawn on a cold December day last year in the city of Manchester, UK, a doping control officer knocked on the door of Ms Jones' hotel room. It was 6:50 am.

The officer asked for a urine sample.

Ms Jones declined to provide one.

As all athletes know, refusing to provide a sample is an offence in itself, punishable by a ban of four years.

DEHYDRATED

At first, Jones said she couldn't provide a urine sample because she was dehydrated, so wasn't ready to use the toilet.

Such excuses have been used before – sometimes athletes do get dehydrated. Normally, the officer would stay with the athlete until she was ready to provide the sample.

But the athlete did not want her to stay and wait. The officer reminded her "approximately five times" of the consequences of a refusal to take such a test—several years of being banned from her sport. Ms Jones continued to refuse.

A phone call was made to the performance director of GB Taekwondo, who advised her to comply.

Again, she refused.

The officer went away with no sample.

CHANGE OF ISSUE

The athlete had a test 12 hours later, which she passed. But 12 hours is a long time in sports—and anyway, but that time, the issue had shifted. Her refusal had become the issue.

The anti-doping officers later received a letter from a lawyer saying their client had made a poor decision because she was dehydrated and it affected her mentally.

Did Jade Jones get the four-year ban? No. She got no punishment at all.

The officers decided to give her the benefit of the doubt. The UK's anti-doping agency approved her to continue competing without a break.

THE CHINESE COMPLIED

Now let's compare this to the Chinese case.

Chinese swimmers were told to take anti-doping tests one day in 2021. They complied, and 23 tested positive for the banned drug trimetazidine.

The athletes expressed puzzlement. They said they had not taken any drugs – but had all shared meals at the Huayang Holiday hotel in Shijiazhuang, a city in Hebei province.

Investigators duly investigated the hotel, and found trace elements of the drug in the kitchen – in the kitchen drains, in the extractor fan, and on spice containers.

But how did the substance get there? It is not normally used in foods.

Anti-doping specialists gave them the benefit of the doubt, and they were cleared without charge.

COVERAGE IS AN ISSUE

There does seem to be an issue here. The Chinese swimmers clearly complied fully with the testing rules, and were cleared – yet there are huge numbers of negative reports about them in the mainstream media, many throwing doubt on their innocence.

In contrast, the UK athlete clearly DID contravene the drug testing rules, but there's little coverage of her case. It is quite possible that there was no drug-taking in either instance.

One of the problems may be the effect of such unbalanced coverage over a long term. There is often massive coverage of Chinese cases, with far less coverage of other cases. So a general prejudice is built up of one side "usually" cheating while the other is assumed to play fair.

But perhaps the best position to take is the one which the drug-testing agencies have taken. If one side gets the benefit of the doubt, then the other should too. The advantage of that position is that it reflects the position of natural justice.

People are innocent until proven guilty.

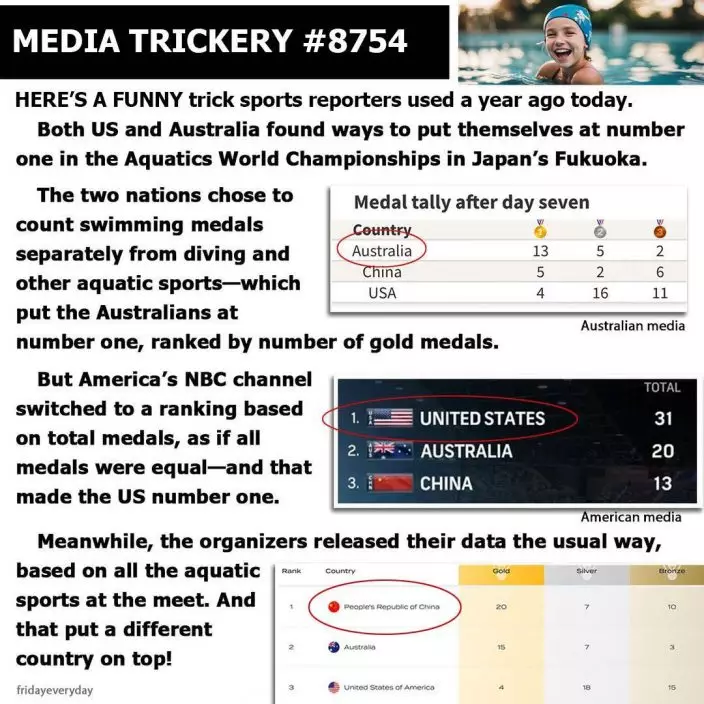

Memories of media trickery:

For more commentary from Nury Vittachi, check out the YouTube video below:

Lai See(利是)

** The blog article is the sole responsibility of the author and does not represent the position of our company. **