AMES, Iowa (AP) — At first glance, it looks like an unassuming farm. Cows are scattered across fenced-in fields. A milking barn sits in the distance with a tractor parked alongside. But the people who work there are not farmers, and other buildings look more like what you’d find at a modern university than in a cow pasture.

Welcome to the National Animal Disease Center, a government research facility in Iowa where 43 scientists work with pigs, cows and other animals, pushing to solve the bird flu outbreak currently spreading through U.S. animals — and develop ways to stop it.

Particularly important is the testing of a cow vaccine designed to stop the continued spread of the virus — thereby, hopefully, reducing the risk that it will someday become a widespread disease in people.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture facility opened in 1961 in Ames, a college town about 45 minutes north of Des Moines. The center is located on a pastoral, 523-acre (212-hectare) site a couple of miles east of Ames' low-slung downtown.

It's a quiet place with a rich history. Through the years, researchers there developed vaccines against various diseases that endanger pigs and cattle, including hog cholera and brucellosis. And work there during the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009 — known at the time as “swine flu” — proved the virus was confined to the respiratory tract of pigs and that pork was safe to eat.

The center has the unusual resources and experience to do that kind of work, said Richard Webby, a prominent flu researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis.

“That’s not a capacity that many places in the U.S. have,” said Webby, who has been collaborating with the Ames facility on the cow vaccine work.

The campus has 93 buildings, including a high-containment laboratory building whose exterior is reminiscent of a modern megachurch but inside features a series of compartmentalized corridors and rooms, some containing infected animals. That’s where scientists work with more dangerous germs, including the H5N1 bird flu. There’s also a building with three floors of offices that houses animal disease researchers as well as a testing center that is a “for animals” version of the CDC labs in Atlanta that identify rare (and sometimes scary) new human infections.

About 660 people work at the campus — roughly a third of them assigned to the animal disease center, which has a $38 million annual budget. They were already busy with a wide range of projects but grew even busier this year after the H5N1 bird flu unexpectedly jumped into U.S. dairy cows.

“It's just amazing how people just dig down and make it work,” said Mark Ackermann, the center's director.

The virus was first identified in 1959 and grew into a widespread and highly lethal menace to migratory birds and domesticated poultry. Meanwhile, the virus evolved, and in the past few years has been detected in a growing number of animals ranging from dogs and cats to sea lions and polar bears.

Despite the spread in different animals, scientists were still surprised this year when infections were suddenly detected in cows — specifically, in the udders and milk of dairy cows. It’s not unusual for bacteria to cause udder infections, but a flu virus?

“Typically we think of influenza as being a respiratory disease,” said Kaitlyn Sarlo Davila, a researcher at the Ames facility.

Much of the research on the disease has been conducted at a USDA poultry research center in Athens, Georgia, but the appearance of the virus in cows pulled the Ames center into the mix.

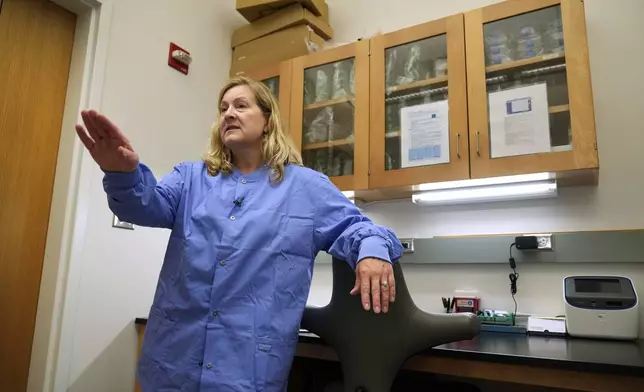

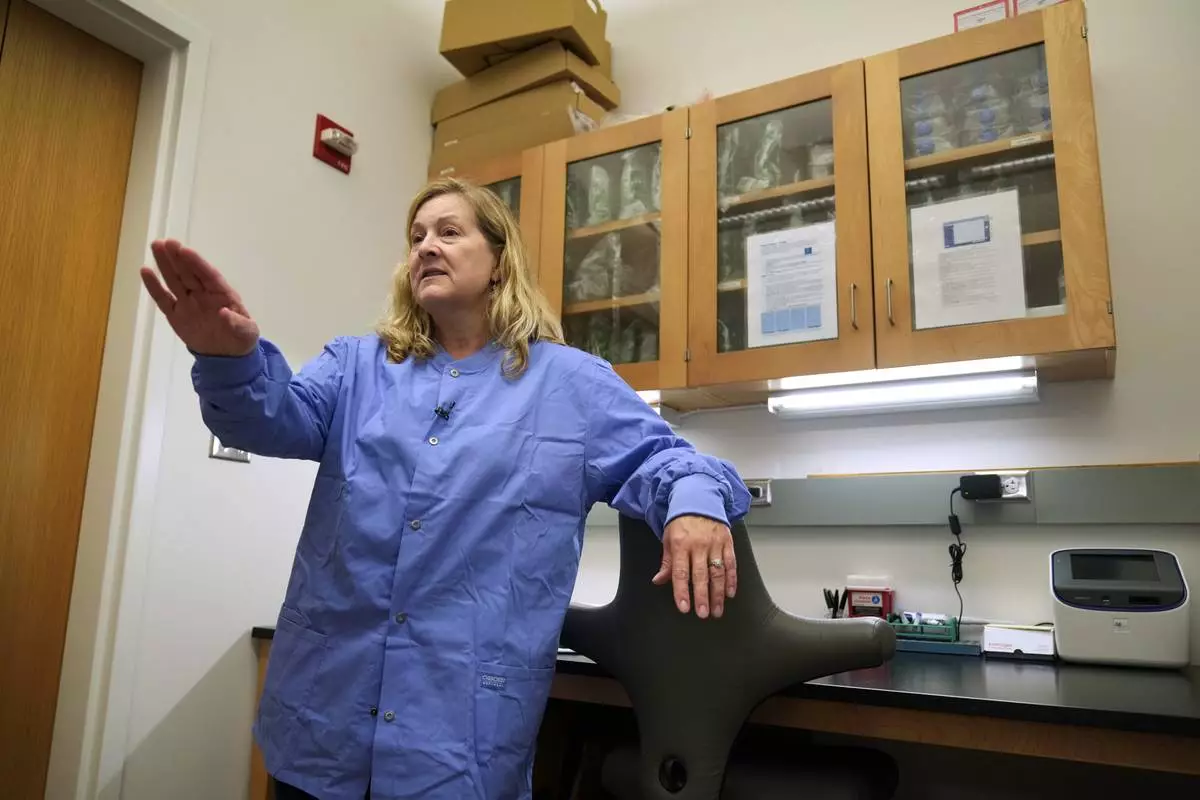

Amy Baker, a researcher who has won awards for her research on flu in pigs, is now testing a vaccine for cows. Preliminary results are expected soon, she said.

USDA spokesperson Shilo Weir called the work promising but early in development. There is not yet an approved bird flu vaccine being used at U.S. poultry farms, and Weir said that while poultry vaccines are being pursued, any such strategy would be challenging and would not be guaranteed to eliminate the virus.

Baker and other researchers also have been working on studies in which they try to see how the virus spreads between cows. That work is going on in the high-containment building, where scientists and animal caretakers don specialized respirators and other protective equipment.

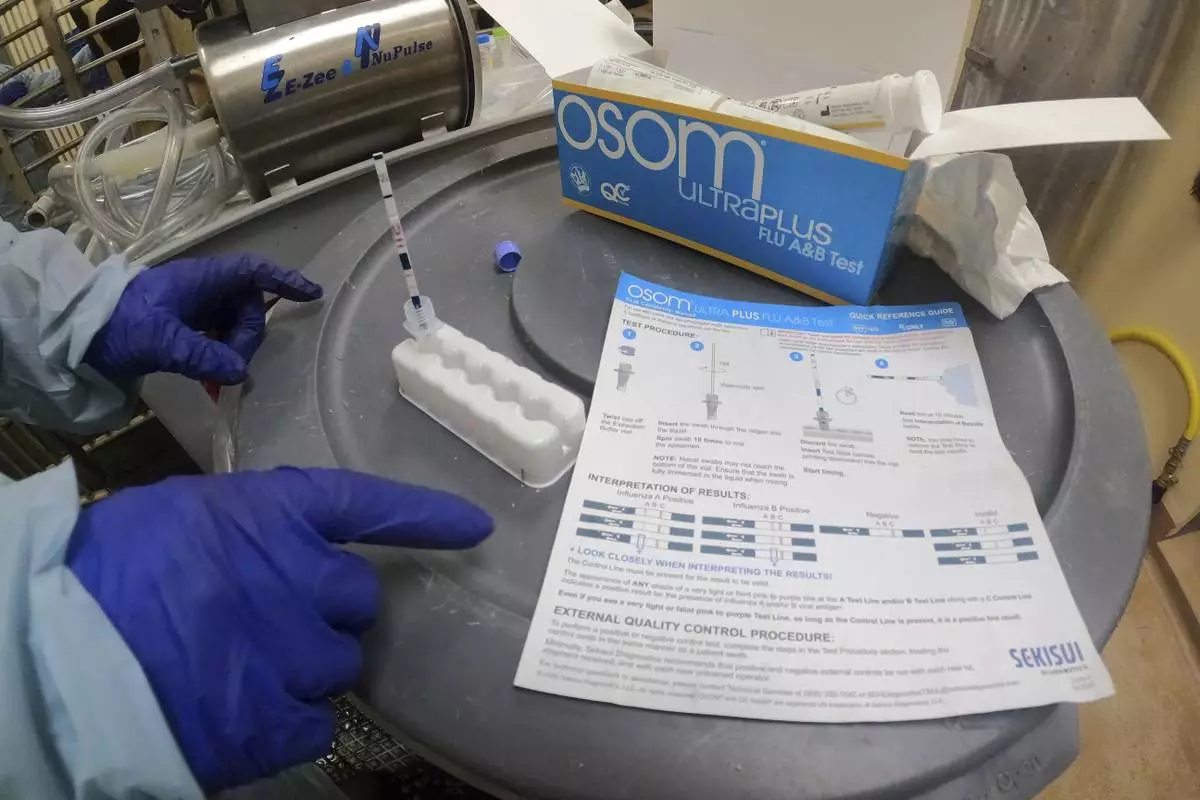

The research exposed four yearling heifers to a virus-carrying mist and then squirted the virus into the teats and udders of two lactating cows. The first four cows got infected but had few symptoms. The second two got sicker — suffering diminished appetite, a drop in milk production and producing thick, yellowish milk.

The conclusion that the virus mainly spread through exposure to milk containing high levels of the virus — which could then spread through shared milking equipment or other means — was consistent with what health investigators understood to be going on. But it was important to do the work because it has sometimes been difficult to get complete information from dairy farms, Webby said.

“At best we had some good hunches about how the virus was circulating, but we didn't really know,” he added.

USDA scientists are doing additional work, checking the blood of calves that drank raw milk for signs of infection.

A study conducted by the Iowa center and several universities concluded that the virus was likely circulating for months before it was officially reported in Texas in March.

The study also noted a new and rare combination of genes in the bird flu virus that spilled over into the cows, and researchers are sorting out whether that enabled it to spread to cows, or among cows, said Tavis Anderson, who helped lead the work.

Either way, the researchers in Ames expect to be busy for years.

“Do they (cows) have their own unique influenzas? Can it go from a cow back into wild birds? Can it go from a cow into a human? Cow into a pig?” Anderson added. “Understanding those dynamics, I think, is the outstanding research question — or one of them.”

Stobbe reported from New York.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

A sign stands outside of the National Centers for Animal Health campus in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Dairy cows stand in a field outside of a milking barn at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Amy Baker speaks in a lab at the National Animal Disease Center in Ames, Iowa, on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. In addition to vaccines, she and other researchers also have been working on studies in which they try to see how the virus spreads between cows. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

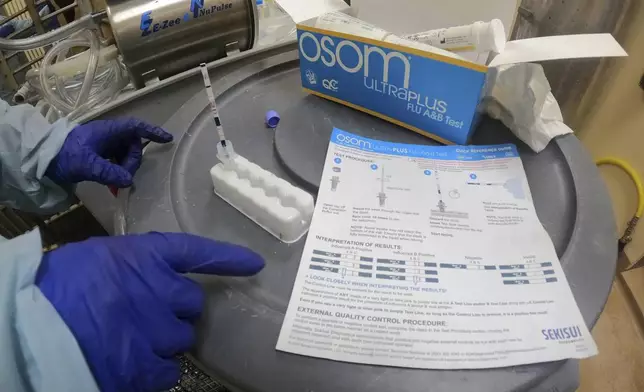

In this photo provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a researcher performs a rapid antigen test on milk from a dairy cow inoculated against bird flu in a containment building at the National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Monday, July 29, 2024. (USDA Agricultural Research Service via AP)

In this photo provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a dairy cow is milked before inoculation against bird flu in a containment building at the National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Friday, July 19, 2024. (USDA Agricultural Research Service via AP)

In this photo provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, an animal caretaker collects a blood sample from a dairy calf vaccinated against bird flu in a containment building at the National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (USDA Agricultural Research Service via AP)

In this photo provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, animal care staff prepare to collect a blood sample from a dairy calf vaccinated against bird flu in a containment building at the National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (USDA Agricultural Research Service via AP)

Vaccinated calves stand in a pen in a large animal containment building at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

A high-containment laboratory building is seen at the National Animal Disease Center in Ames, Iowa, on Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Calves stand in a pen at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

A cow stands in a field at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Dairy cows stand in a field outside of a milking barn at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

A cow stands in a feeding pen at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

A large animal containment building is seen on the campus of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

Dairy cows stand in a field outside of a milking barn at the U.S. Department of Agriculture's National Animal Disease Center research facility in Ames, Iowa, on Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)