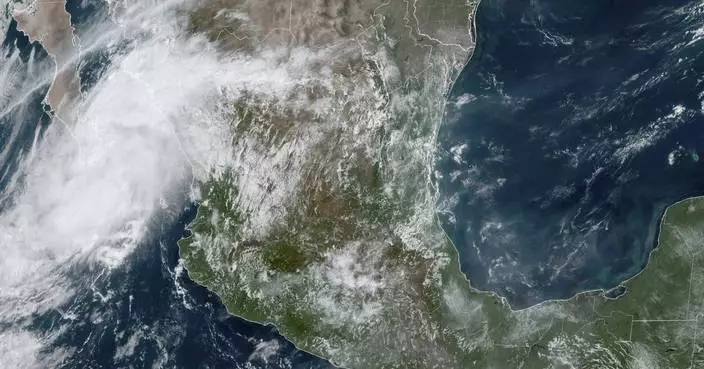

For the first time in more than a century, salmon will soon have free passage along the Klamath River and its tributaries — a major watershed near the California-Oregon border — as the largest dam removal project in U.S. history nears completion.

Crews will use excavators this week to breach rock dams that have been diverting water upstream of two dams that were already almost completely removed, Iron Gate and Copco No. 1. The work will allow the river to flow freely in its historic channel, giving salmon a passageway to key swaths of habitat just in time for the fall Chinook, or king salmon, spawning season.

“Seeing the river being restored to its original channel and that dam gone, it’s a good omen for our future,” said Leaf Hillman, ceremonial leader of the Karuk Tribe, which has spent at least 25 years fighting for the removal of the Klamath dams. Salmon are culturally and spiritually significant to the tribe, along with others in the region.

The demolition comes about a month before removal of four towering dams on the Klamath was set to be completed as part of a national movement to let rivers return to their natural flow and to restore ecosystems for fish and other wildlife.

As of February, more than 2,000 dams had been removed in the U.S., the majority in the last 25 years, according to the advocacy group American Rivers. Among them were dams on Washington state’s Elwha River, which flows out of Olympic National Park into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and Condit Dam on the White Salmon River, a tributary of the Columbia.

“Now the healing can really begin as far as the river restoring itself,” said Joshua Chenoweth, senior riparian ecologist for the Yurok Tribe, which has spent decades fighting to remove the dams and restore the river. “Humans can do a lot to help that along, but what we’ve learned on Elwha and Condit and other dams is that really you just have to remove the dams, and then rivers are really good at kind of returning to a natural state.”

The Klamath was once known as the third-largest salmon-producing river on the West Coast. But after power company PacifiCorp built the dams to generate electricity between 1918 and 1962, the structures halted the natural flow of the river and disrupted the lifecycle of the region's salmon, which spend most of their life in the Pacific Ocean but return up their natal rivers to spawn.

The fish population dwindled dramatically. In 2002, a bacterial outbreak caused by low water and warm temperatures killed more than 34,000 fish, mostly Chinook salmon. That jumpstarted decades of advocacy from tribes and environmental groups, culminating in 2022 when federal regulators approved a plan to remove the dams.

Since then, the smallest of the four dams, known as Copco No. 2, has been removed. Crews also drained the other three dams’ reservoirs and started removing those structures in March.

Along the Klamath, the dam removals won’t be a major hit to the power supply. At full capacity, they produced less than 2% of PacifiCorp’s energy — enough to power about 70,000 homes. Hydroelectric power produced by dams is considered a clean, renewable source of energy, but many larger dams in the U.S. West have become a target for environmental groups and tribes because of the harm they cause to fish and river ecosystems.

The project was expected to cost about $500 million — paid for by taxpayers and PacifiCorps ratepayers.

But it's unclear how quickly salmon will return to their historical habitats and the river will heal. There have already been reports of salmon at the mouth of the river, starting their river journey. Michael Belchik, senior water policy analyst for the Yurok Tribe, said he is hopeful they’ll get past the Iron Gate dam soon.

“I think we’re going to have some early successes,” he said. “I’m pretty confident we’ll see some fish going above the dam. If not this year, then for sure next year.”

There are two other Klamath dams farther upstream, but they are smaller and allow salmon to pass via fish ladders — a series of pools that fish can leap through to get past the dam.

Mark Bransom, chief executive of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the nonprofit entity created to oversee the project, noted that it took about a decade for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe to start fishing again after the removal of the Elwha dams.

“I don’t know if anybody knows with any certainty what it means for the return of fish,” he said. “It’ll take some time. You can’t undo 100 years’ worth of damage and impacts to a river system overnight.”

This image provided by Swiftwater Films shows a downstream view of crews working at the Iron Gate coffer dam site along the Klamath River on Tuesday, Aug. 27, 2024, in Siskiyou County, Calif. (Shane Anderson/Swiftwater Films via AP)

FILE - Excess water spills over the top of a dam on the Lower Klamath River known as Copco 1 near Hornbrook, Calif. (AP Photo/Gillian Flaccus, File)

FILE - A view shows the Copco 1 Dam in Hornbrook, Calif., Sunday, Sept. 17, 2023. (AP Photo/Haven Daley, File)

FILE - The Klamath River head gates are seen here on Wednesday, June 9, 2021, in Klamath Falls, Ore. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard, File)

FILE - The Iron Gate Dam powerhouse and spillway are seen on the lower Klamath River near Hornbrook, Calif., on March 2, 2020. (AP Photo/Gillian Flaccus, File)

FILE - Jamie Holt, lead fisheries technician for the Yurok Tribe, right, and Gilbert Myers count dead chinook salmon pulled from a trap in the lower Klamath River on June 8, 2021, in Weitchpec, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard, File)

FILE - Gilbert Myers takes a water temperature reading at a chinook salmon trap in the lower Klamath River in California on June 8, 2021. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard, File)

FILE - The Klamath River winds runs along Highway 96 on June 7, 2021, near Happy Camp, Calif. (AP Photo/Nathan Howard, File)

FILE - A dam on the lower Klamath River known as Copco 2 is seen near Hornbrook, Calif., on March 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Gillian Flaccus, File)