MEXICO CITY (AP) — According to official figures, at least 115,000 people have disappeared in Mexico since 1952, though the real number is believed to be higher.

During the country’s “dirty war,” a conflict that lasted throughout the 1970s, disappearances were attributed to government repression.

In the past two decades, as officials have fought drug cartels and organized crime has tightened its grip in several states, it’s been more difficult to trace the perpetrators and causes of disappearances.

Human trafficking, kidnapping, acts of retaliation and forced recruitment by cartel members are among the reasons listed by human rights organizations. Disappearances impact local communities as well as migrants who travel through Mexico hoping to reach the U.S.

Among the thousands of relatives affected are mothers whose children have vanished.

Here are some takeaways from the AP’s report on how some of these women have taken the search in their own hands, supported by a few faith leaders who offer spiritual guidance.

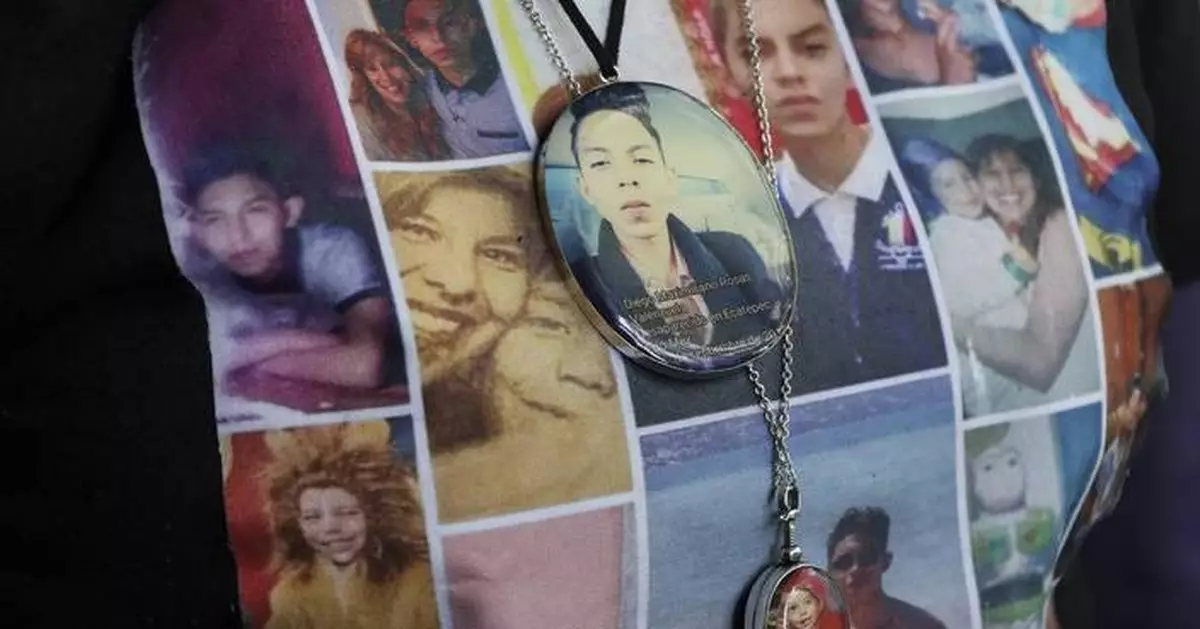

Diego Maximiliano was 16 years old when he vanished in 2015 after leaving home to meet with friends. He and his mother, Verónica Rosas, lived in Ecatepec, a Mexico City suburb where robbery, femicide and other violent crimes have afflicted its inhabitants for decades.

Kidnappers took him and requested an amount of money that Rosas was unable to get. They apparently agreed to a lower sum, but Diego was never released.

To find their relatives, people like Rosas initially trust the authorities, but as time passes and no answers or justice comes, they take the search into their own hands.

They distribute bulletins with photos of the missing person. They visit morgues, prisons and psychiatric institutions. They walk through neighborhoods where homeless people spend the day, wondering if their sons or daughters might be close, affected by drug abuse or mental health problems.

Three months after Diego’s disappearance, Rosas got tired of waiting to hear from the police. She opened a Facebook page called “Help me find Diego” and, though she was frightened of stepping out of her home, she started looking for him, dead or alive.

For three years, her search was lonely. Relatives, co-workers and friends commonly distance themselves from people with missing family members, claiming that “they only talk about their search” or “listening to them is too sad.”

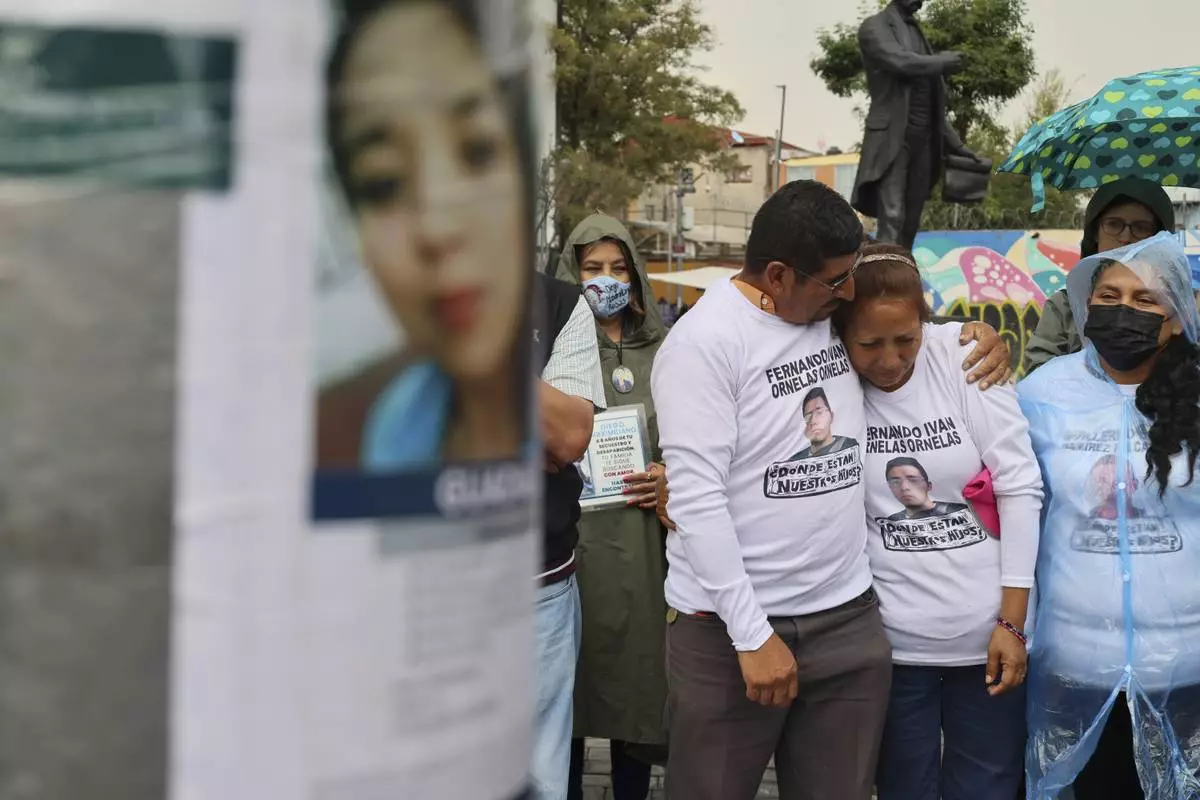

It wasn't until 2018 that Rosas joined an annual protest in which thousands of mothers demand answers and justice and became aware of a wider problem. After meeting other women like her, she wondered: What if we use our collective force in our favor?

And so, as other mothers have done in Mexican states like Sonora and Jalisco, Rosas created an organization to provide mutual support for their searches. She called it “ Uniendo Esperanzas,” or Gathering Hopes, and it currently supports 22 families, mostly from the state of Mexico.

The resentment and disappointment from Mexicans affected by nationwide violence has increased recently.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Claudia Sheinbaum, who will succeed him on Oct. 1, constantly minimize the relatives’ recriminations, claiming that homicide rates decreased during the current administration.

But it’s not just violence that victims resent. On a recent evening, in the state of Zacatecas, a mother like Rosas stormed into a session of Congress. Drenched in tears, she screamed that she found her son — with a gunshot to the head — at the morgue. He had been there since November 2023, she said, but the authorities failed to notify her in spite of her tireless efforts to get information about what happened to him.

Many faith leaders — regardless of their religious affiliation — are unwilling to address the disappearances in Mexico or to console anguished mothers.

“Not everyone has the sensitivity to endure such pain,” said Catholic Bishop Javier Acero, who meets regularly with mothers like Rosas. He pushed for celebrating Mass in Mexico City's Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe to remember their disappeared children for the first time in 2023.

“But the numbers of disappearances keep rising and the government doesn’t do anything about it, so, where the state is absent, the church offers guidance,” Acero said.

Some mothers regard him as an ally, and leaders from the Catholic church have raised their concerns against Lopez Obrador’s security policy since two Jesuit priests were murdered in 2022. But, in parallel, some relatives of missing people claim that many Catholic priests, nuns and parishioners have shown little empathy for their pain.

Soon after her son disappeared, Rosas rushed to a nearby parish and asked the priest to celebrate Mass so she could pray for Diego, but he refused.

She said he told her, “I can’t say that people are being kidnapped, madam. I encourage you to pray for your son’s eternal rest.”

In contrast, faith leaders from an ecumenical group called “The Axis of Churches” are constantly supportive. Methodists, evangelicals, Indigenous spiritual leaders, theologians and feminists are among its members. Sometimes they pray; on other occasions they share a meal, draw mandalas or simply listen to the mothers.

“We have the legitimate hope of finding our treasures alive,” said the Rev. Arturo Carrasco, an Anglican priest who offers spiritual guidance to families with missing members. “We are no fools and we understand that there’s a risk they might be dead. But as long as we have no evidence of that, we will keep searching.”

Like Carrasco, Catholic nun Paola Clericó has walked with the mothers through muddy terrain where excavations were made in search for human remains. They have celebrated Mass in the middle of busy streets and next to canal drainages. They have joined them in visiting prisons and morgues, comforting them no matter what sorrow may come.

“We live with a such a profound pain that only God can help us endure it,” Rosas said. “If it wasn’t for that light, for that relief, I don’t think we would be able to still stand.”

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

Husband and wife Marcos Vazquez and Benita Ornelas, from the search collective "Uniendo Esperanzas" or Uniting Hope, attend an Anglican Mass on the fifth anniversary of the disappearance of their son Fernando Ivan Ornelas in Mexico City, Sunday, July 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ginnette Riquelme)

A statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe holds a photo of Veronica Rosas with her son Diego Maximiliano in Ecatepec, Mexico, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. Diego went missing when he was 16 years old on Sept. 4, 2015. (AP Photo/Ginnette Riquelme)

Veronica Rosas poses for a portrait in the bedroom of her missing son Diego Maximiliano in Ecatepec, Mexico, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. Rosas' son went missing when he was 16 years old on Sept. 4, 2015. (AP Photo/Ginnette Riquelme)

Members of the search collective "Uniendo Esperanzas" or Uniting Hope, use the tip of an iron rod to search for the smell of human remains under the earth, in a forest in the State of Mexico, Mexico, Friday, Aug. 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Ginnette Riquelme)

Catholic nun Paola Clericó, holding a poster of missing person Fernando Ivan Ornelas, and Veronica Rosas with a photo of her missing son Diego, ask a resident if he recognizes either man and invite him to join a Mass with members of their search collective "Uniendo Esperanzas" or Uniting Hope, in Mexico City, Sunday, July 21, 2024. The collective of people with missing family members held a Mass on the birthday of Ornelas who disappeared five years prior. (AP Photo/Ginnette Riquelme)

Photos of Veronica Rosas and her son Diego decorate Veronica's shirt and necklaces, as she poses for a portrait at her home in Ecatepec, Mexico, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. Rosas' son went missing when he was 16 years old on Sept. 4, 2015. (AP Photo/Ginnette Riquelme)