WASHINGTON (AP) — It could be a well-rehearsed zinger, a too-loud sigh — or a full performance befuddled enough to shockingly end a sitting president's reelection bid.

Notable moments from past presidential debates demonstrate how the candidates’ words and body language can make them look especially relatable or hopelessly out-of-touch — showcasing if a candidate is at the top of their policy game or out to sea. Will past be prologue when Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump debate in Philadelphia on Tuesday?

“Being live television events, without a script, without any way of knowing how they are going to evolve — anything can happen,” said Alan Schroeder, author of “Presidential Debates: 50 years of High-Risk TV.”

Here’s a look at some highs, lows and curveballs from presidential debates past.

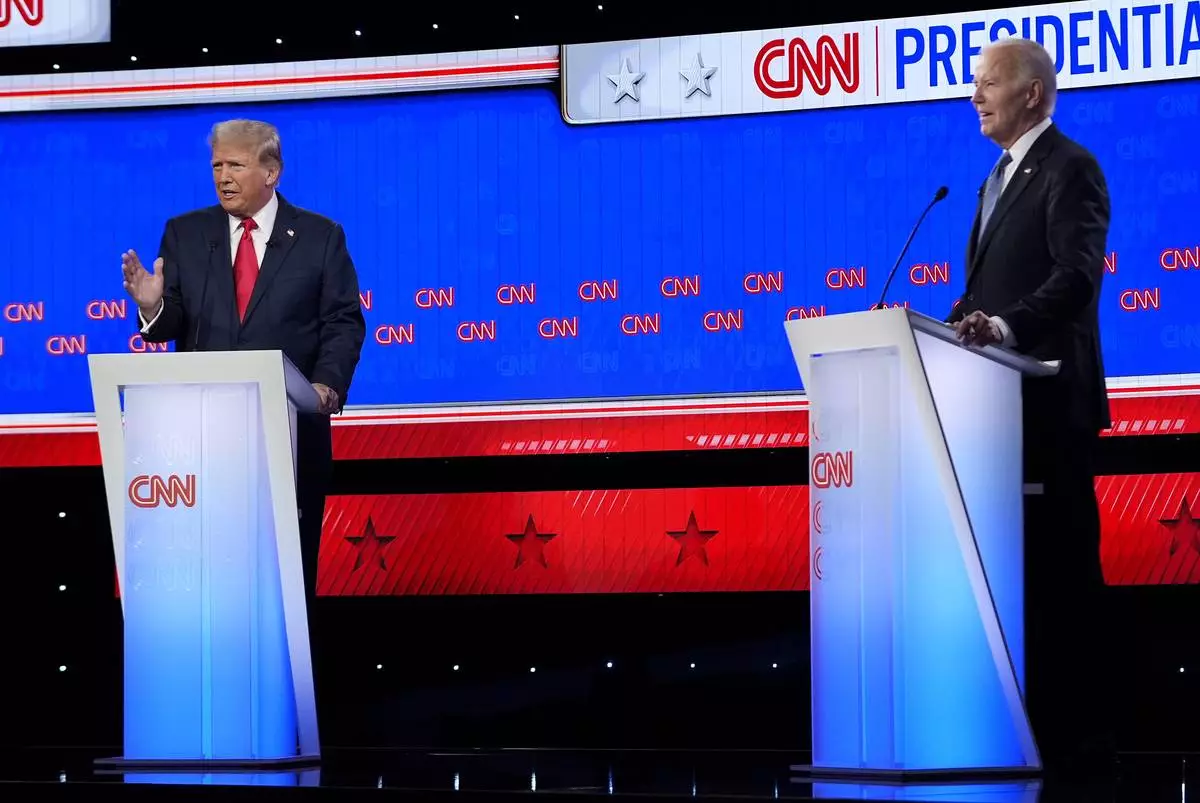

Though it's still fresh in the nation's mind, the June debate in Atlanta pitting President Joe Biden against Trump may go down as the most impactful political faceoff in history.

Biden, 81, shuffled onto the stage, frequently cleared his throat, said $15 when he meant that his administration helped cut the price of insulin to $35 per month on his first answer and inexplicably gave Trump an early chance to pounce on the chaotic 2021 withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. It got even worse for the president 12 minutes in, when Biden appeared lose his train of thought entirely.

“The, uh — excuse me, with the COVID, um, dealing with, everything we had to do with, uh ... if ... Look ...” Biden stammered before concluding ”we finally beat Medicare." He meant that his administration had successfully taken on “big pharma,” some of the nation's top prescription drug companies.

Biden at first blamed having a cold, then suggested he'd overprepared. Later, he pointed to jetlag after pre-debate travel overseas.

In the frantic hours immediately after the debate, a Biden campaign spokesperson said, “ Of course, he's not dropping out.” That was correct until 28 days later, when the president did just that, bowing out and endorsing Harris on July 21.

Biden was asked in Atlanta about his age and got into an argument with Trump over golf. It was the opposite of knowing a sensitive question was coming and still making the answer sound spontaneous — a feat President Ronald Reagan pulled off while landing a line for the ages during 1984's second presidential debate.

Reagan was 73 and facing 56-year-old Democratic challenger Walter Mondale. In the first debate, Reagan struggled to remember facts and occasionally looked confused. An adviser suggested afterward that aides “filled his head with so many facts and figures that he lost his spontaneity.”

So Reagan’s team took a more hands-off approach toward the second debate. When Reagan got a question about his mental and physical stamina that he had to know was coming, he was ready enough to make the response feel unplanned.

Asked whether his age might hinder his handling of major challenges, Raegan responded, “Not at all,” before smoothly continuing: “I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” The audience, and even Mondale, cracked up.

Then, capitalizing on years of Hollywood-honed comedic training, the president took a sip of water, giving the crowd more time to laugh. Finally, he grinned and left little doubt that he’d rehearsed, adding, “It was Seneca, or it was Cicero, I don’t know which, that said, ‘If it was not for the elders correcting the mistakes of the young, there would be no state.’”

Years later, Mondale conceded, "That was really the end of my campaign that night.”

Reagan is further remembered for using a light touch to neutralize criticisms from Democratic President Jimmy Carter in a 1980 debate. When Carter accused him of wanting to cut Medicare, Reagan scolded, “There you go again.”

The line worked so well that he turned it into something of a trademark rejoinder going forward.

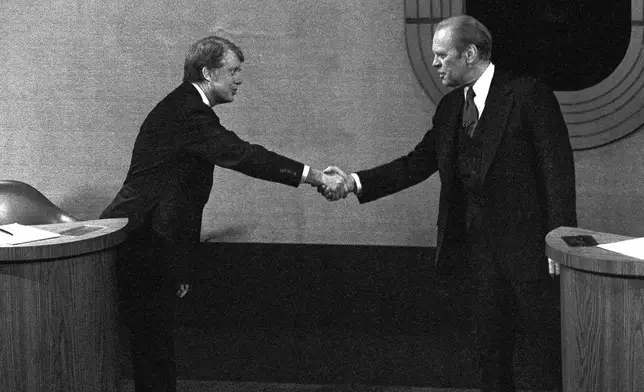

In 1976, Republican President Gerald Ford had a notable moment in a debate against Carter — and not in a good way. The president declared that there is “no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration.”

With Moscow controlling much of that part of the world, the surprised moderator asked if he’d understood correctly. Ford stood by his answer, then spent days on the campaign trail trying to explain it away. He lost that November.

Another awkward moment came in 2012, when Republican nominee Mitt Romney got a debate question about gender pay equality and recalled soliciting women’s groups' help to find qualified female applicants for state posts: “They brought us whole binders full of women.”

Aaron Kall, director of the University of Michigan's debate program, said key lines affect not just who a debate's perceived winner is but also fundraising and media coverage for days, or even weeks, afterward.

“The closer the election, the more zingers and important debate lines can matter,” Kall said.

Not all slips have a devastating impact, though.

Then-Sen. Barack Obama, in a 2008 Democratic presidential primary debate, dismissively told Hillary Clinton, “You’re likable enough, Hillary.” That drew backlash, but Obama recovered.

The same couldn’t be said for the short-lived 2012 Republican primary White House bid of then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry. Despite repeated attempts and excruciatingly long pauses, Perry could not remember the third of the three federal agencies he’d promised to shutter if elected.

Finally, he sheepishly muttered, “Oops.”

The Energy Department, which he later ran during the Trump administration, is what slipped his mind.

Another damaging moment opened a 1988 presidential debate, when Democrat Michael Dukakis was pressed about his opposition to capital punishment in a question that evoked his wife.

“If Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?” CNN anchor Bernard Shaw asked. Dukakis showed little emotion, responding, “I don’t see any evidence that it’s a deterrent.”

Dukakis later said he wished he’d said that his wife “is the most precious thing, she and my family, that I have in this world.”

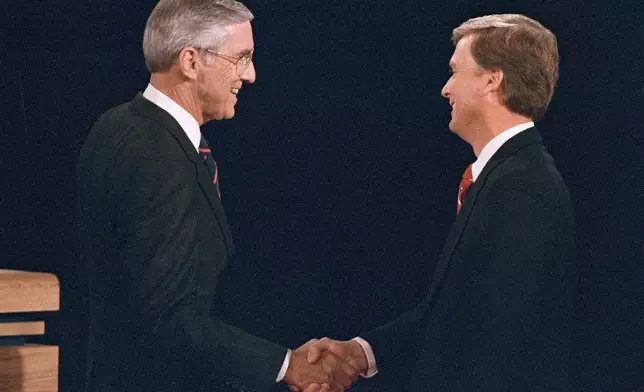

That year’s vice presidential debate featured one of the best-remembered, pre-planned one-liners.

When Republican Dan Quayle compared himself to John F. Kennedy while debating Lloyd Bentsen, the Democrat was ready. He’d studied Quayle’s campaigning and seen him invoke Kennedy in the past.

“Senator, I served with Jack Kennedy. I knew Jack Kennedy,” Bentsen began slowly and deliberately, drawing out the moment. “Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy.”

The audience erupted in applause and laughter. Quayle was left to stare straight ahead.

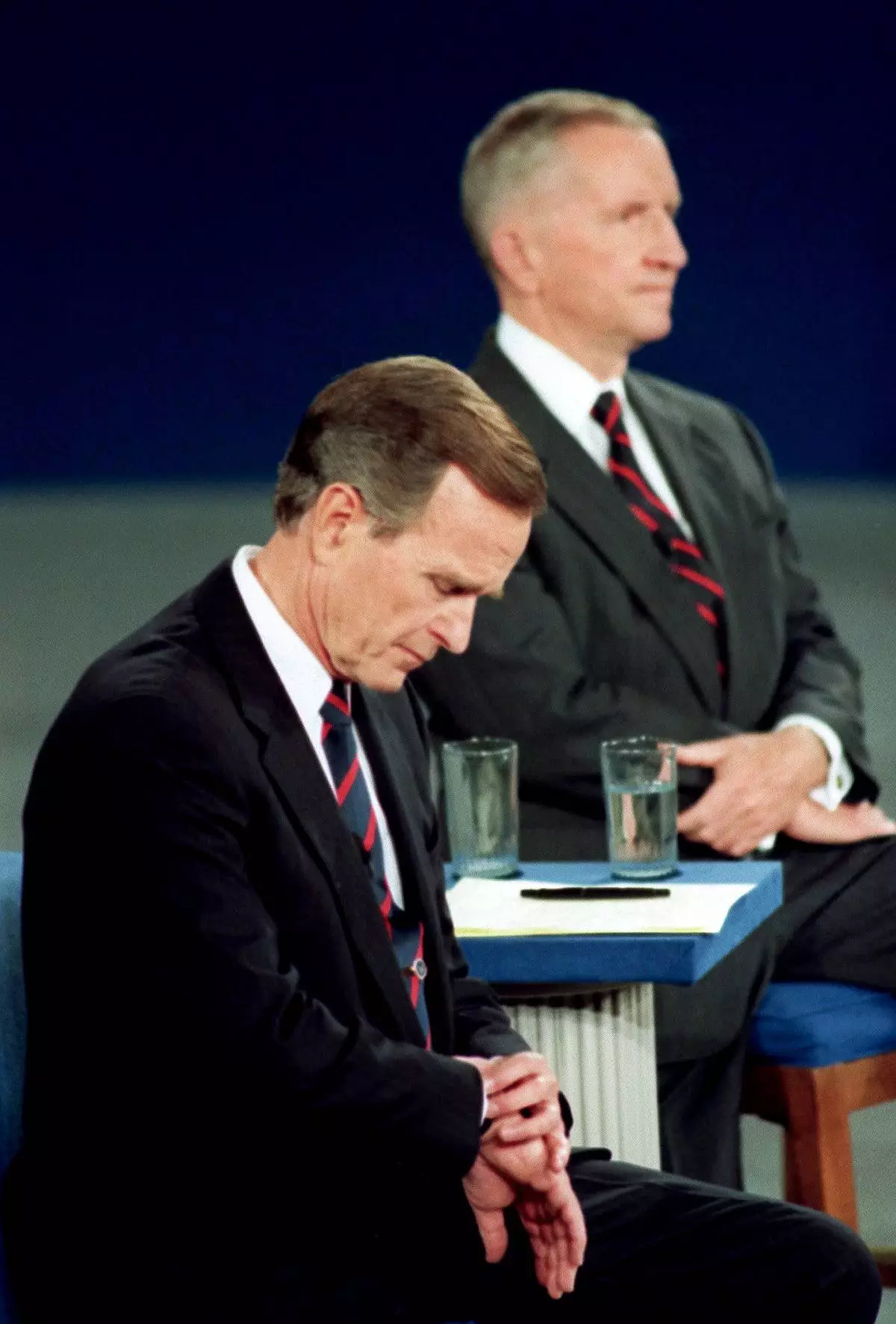

Quayle and George H.W. Bush still easily won the 1988 election. But they lost in 1992 after then-President Bush was caught on camera looking at his watch while Democrat Bill Clinton talked to an audience member during a town hall debate. Some thought it made Bush look bored and aloof.

In another instance of a nonverbal debate miscue, then-Democratic Vice President Al Gore was criticized for a subpar opening 2000 debate performance with Republican George W. Bush in which he repeatedly and very audibly sighed.

During their second, town hall-style debate, Gore moved so close to Bush while the Republican answered one question that Bush finally looked over and offered a confident nod, drawing laughter from the audience.

A similar moment occurred in 2016, as Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton faced the audience to answer questions during a debate with Trump. Trump moved in close behind her, narrowed his eyes and glowered.

Clinton later wrote of the incident: “He was literally breathing down my neck. My skin crawled.”

That didn't stop Trump from claiming the presidency a few weeks later.

Follow the AP’s coverage of the 2024 election at https://apnews.com/hub/election-2024.

FILE - President George H.W. Bush looks at his watch during the 1992 presidential campaign debate with other candidates, Independent Ross Perot, top, and Democrat Bill Clinton, not shown, at the University of Richmond, Va., Oct. 15, 1992. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File)

FILE - Sen. Lloyd Bentsen, D-Texas, left, shakes hands with Sen. Dan Quayle, R-Ind., before the start of their vice presidential debate at the Omaha Civic Auditorium, Omaha, Neb., Oct. 5, 1988. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File)

FILE - Jimmy Carter, left, and Gerald Ford, right, shake hands before the third presidential debate, Oct. 22, 1976, in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/File)

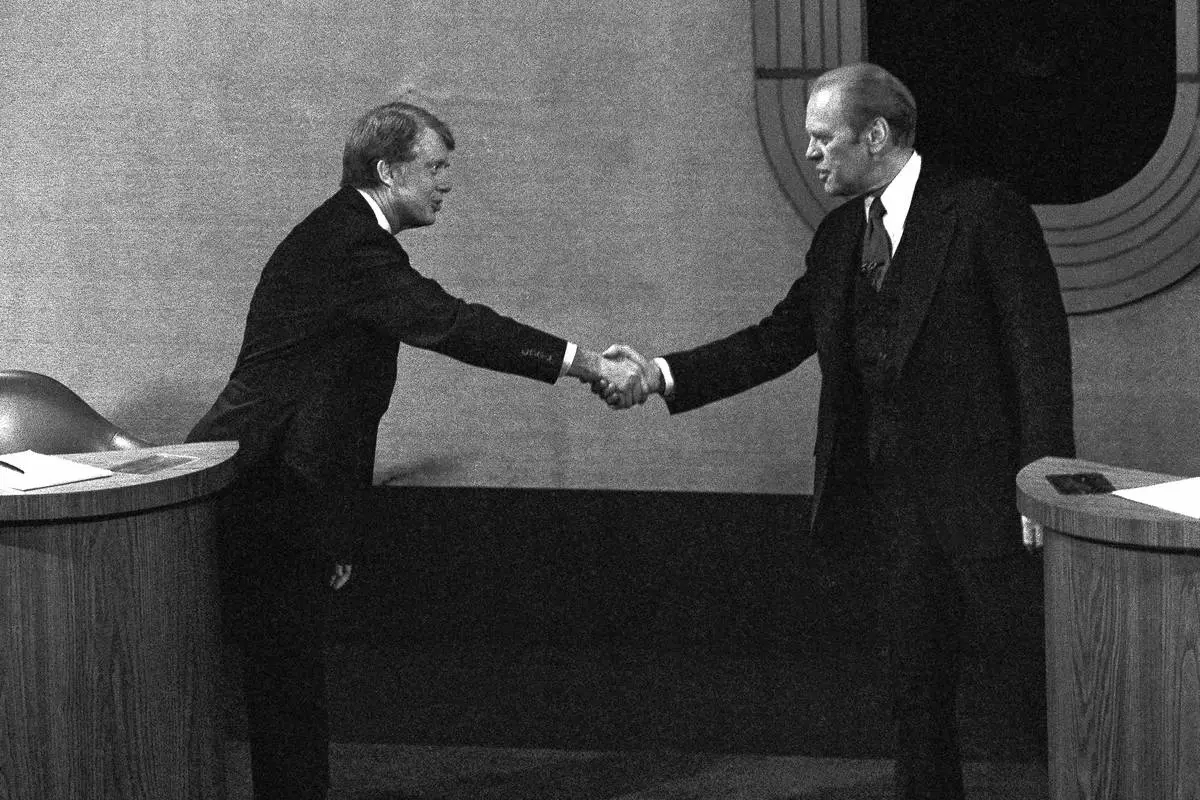

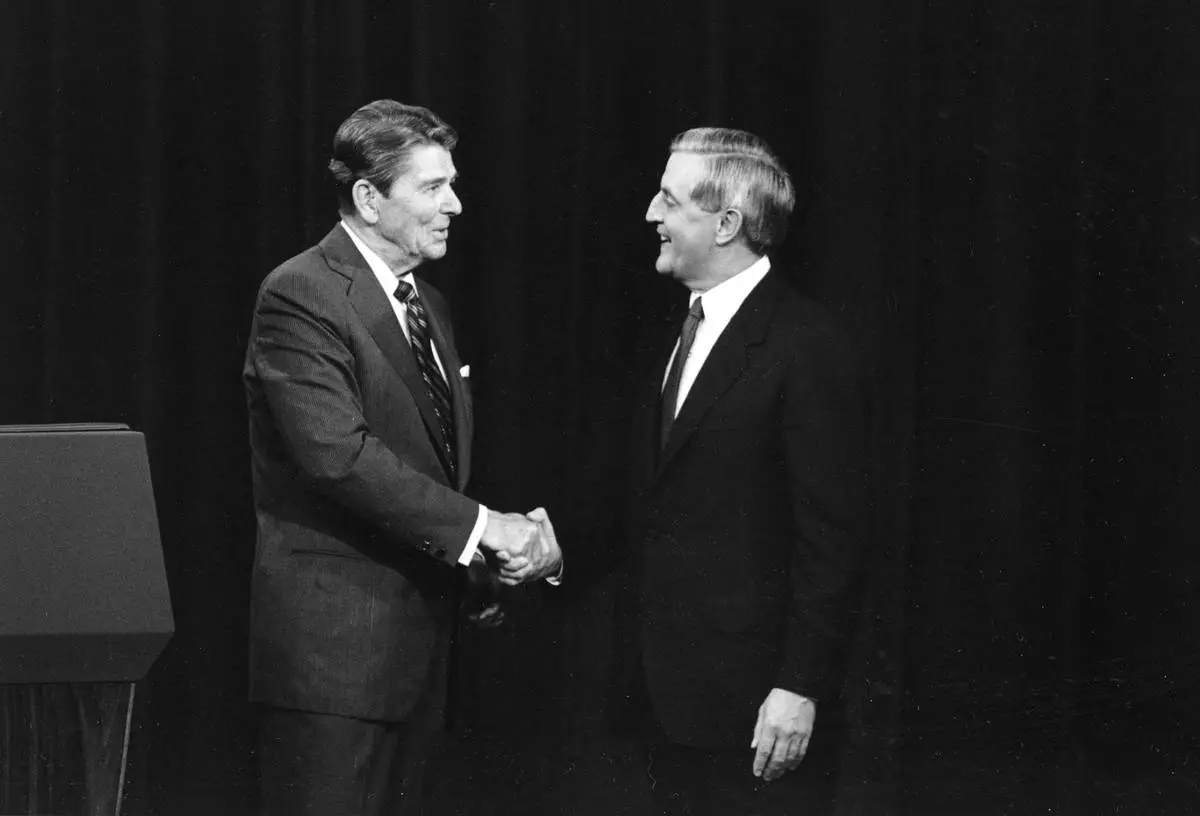

FILE - President Ronald Reagan, left, and his Democratic challenger Walter Mondale, shake hands before debating in Kansas City, Mo., Oct. 22, 1984. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File)

FILE - President Joe Biden, right, and Republican presidential candidate former President Donald Trump, left, during a presidential debate June 27, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert, File)