HONG KONG (AP) — In months, Lo Yuet-ping will bid farewell to a centuries-old village he has called home in Hong Kong for more than seven decades.

The Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon is filled with small houses built from metal sheets and stones, as well as old granite buildings, contrasting sharply with the high-rise structures that dominate much of the Asian financial hub.

Click to Gallery

HONG KONG (AP) — In months, Lo Yuet-ping will bid farewell to a centuries-old village he has called home in Hong Kong for more than seven decades.

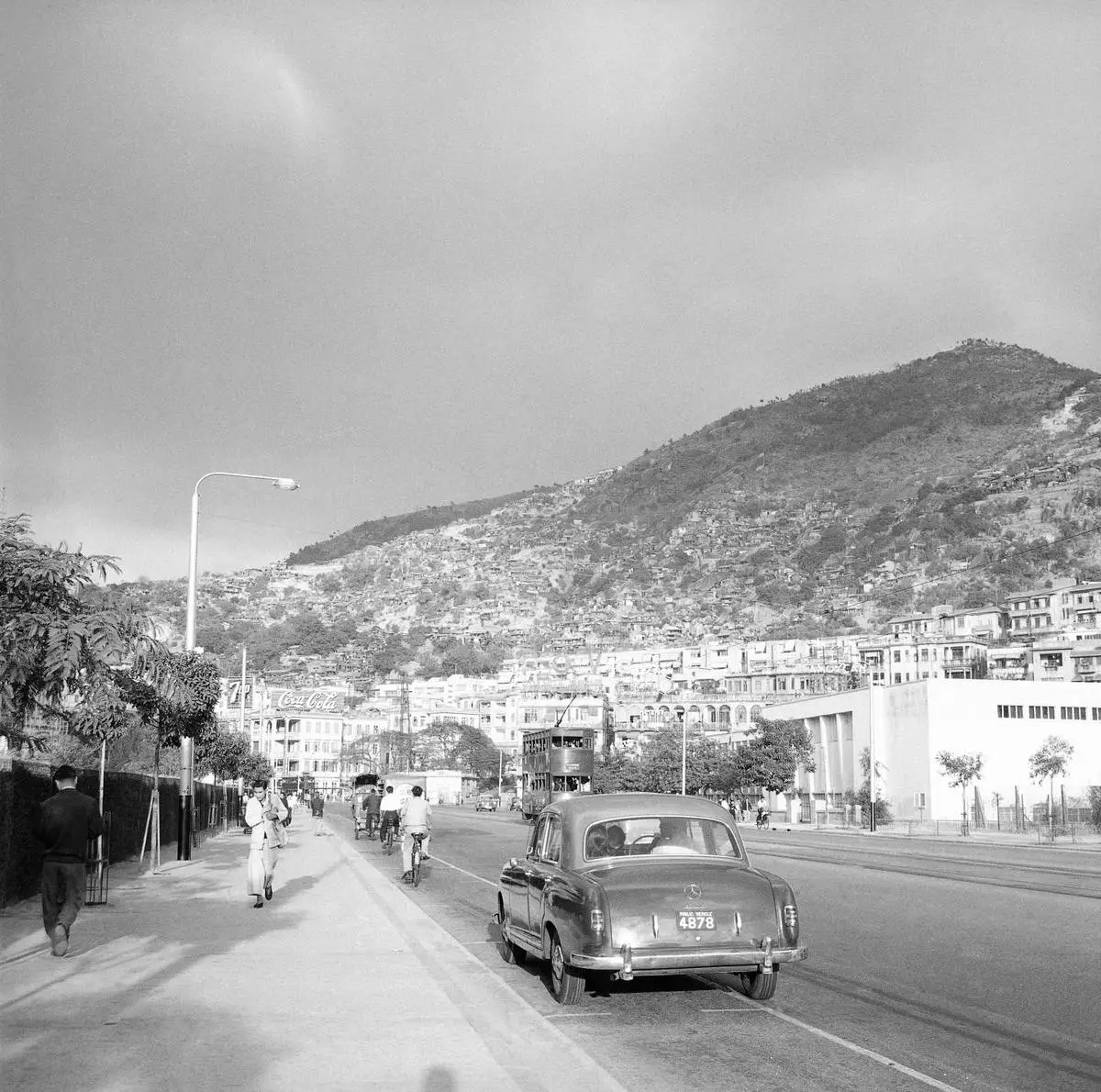

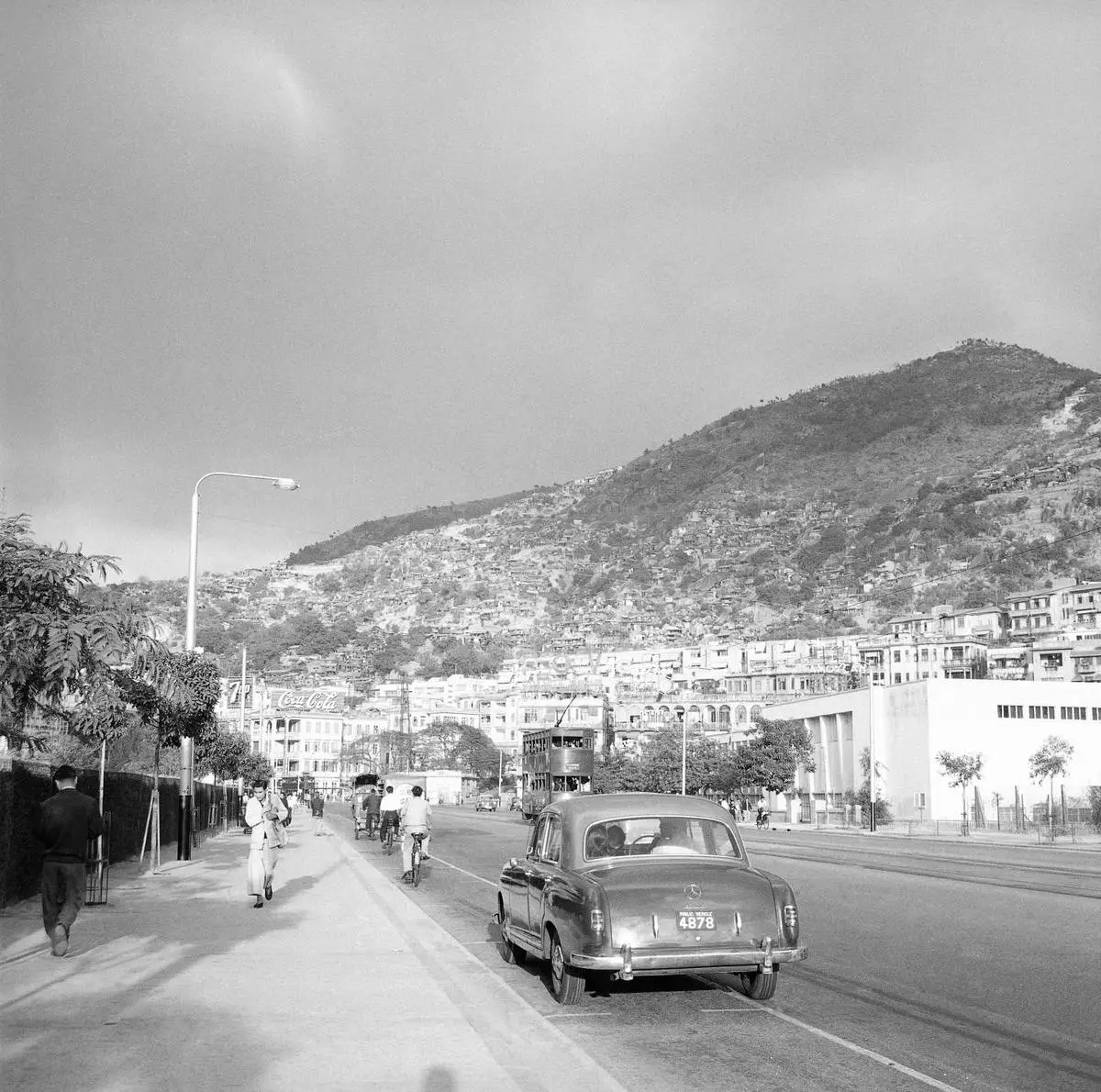

FILE- View of Hong Kong 's hillsides with "squatter" huts of refugees in this photo from 1959. (AP Photo/Fred Waters, File)

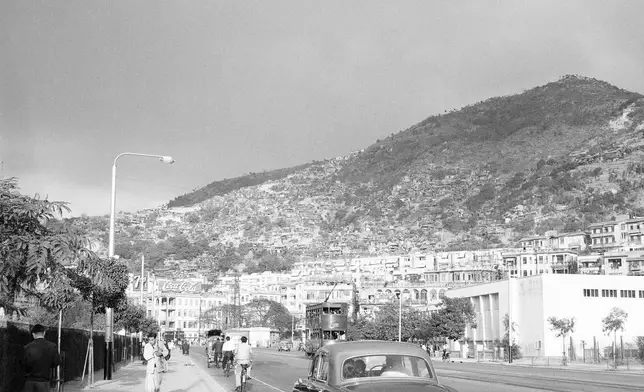

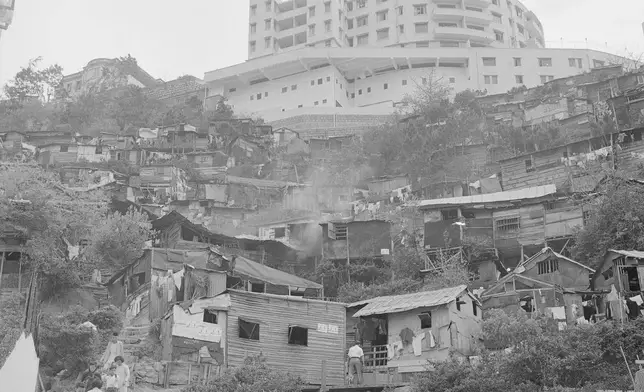

FILE- Perched high on a hill, a shiny new apartment house looks down upon a settlement of squatters' huts in the British crown colony of Hong Kong on May 16, 1956. (AP Photo/File)

A villager tends her store at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A general view of the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

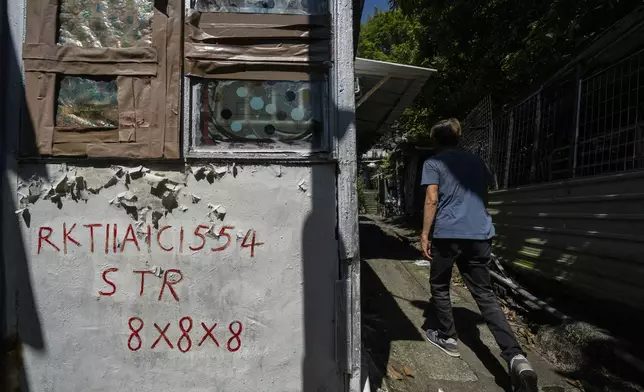

Villager Lo Yuet-ping walks past squatter registration info written on the walls of a house in Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

The flags of China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) are flown at the entrance to the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

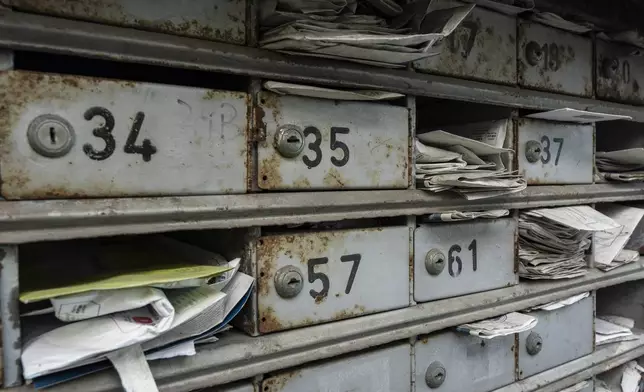

Letterboxes stuffed with mails are seen at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A general view of the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A elderly villager attends to his laundry at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A villager walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Laundry are hung to dry at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping attends to his laundry at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong poses for a photo as she tends to her vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong dries her harvested vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong dries her harvested vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong tends to her vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A villager walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Teoh Bee Hua, a Malaysian who moved to Cha Kwo Ling after marrying a villager in 1973, poses for a photo at her grocery shop in the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. She has kept operating her grocery shop there even though she no longer lives in the village after a fire. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A villager walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping holds up an old black and white photo where he can be seen in the second from top right at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping carries the head prop that's used in the traditional "Qilin" Dance at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping cleans the head prop that's used in the traditional "Qilin" Dance at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lo, 72, has spent his entire life here and is among an estimated 860 households required to move under a government redevelopment plan. He said he will miss the rich history, unique culture and warm interpersonal kindness that defined life in the village.

“I'm unwilling to part with anything,” said Lo, who expects to be relocated to a newer district of east Kowloon.

The ongoing demolition of the Cha Kwo Ling village, set to enter its final phase in 2025, is erasing one of Hong Kong’s last remaining squatter villages, making way for public housing. This settlement has witnessed the former British colony’s transformation from a fishing village to an industrial hub and finally to a global financial center.

Originally a settlement for the Hakka people, a Han Chinese group, Cha Kwo Ling saw an influx of mainland Chinese immigrants over the years, just like other squatter villages in the city.

Some of the immigrants arrived in the city between late 1940s and 1950s, fleeing the civil war in China or seeking better economic opportunities. The influx swelled Hong Kong’s population from 600,000 in 1945 to 2 million by 1950, according to a government's website. Unable to afford housing, many people built wooden homes in squatter villages. In 1953, an estimated 300,000 people were living in such settlements across the city.

Researcher Charles Fung, co-author of a book on the city’s squatter housing, described how people built squatter houses as part of a “catch-me-if-you-can game” with the authorities in British colonial times. Fung explained that the government wouldn’t have to provide resettlement commitments for homeowners if it managed to demolish the structures before people moved into them. This led people to cut wood and build houses at night along hillsides where they were difficult to find, he said.

While the structures looked vulnerable, Fung said, the villages played a crucial role in supporting Hong Kong’s economy. They hosted small factories and were located near industrial zones, informally bolstering the city’s factory system during its time as a manufacturing hub, he said.

However, the precarious nature of the settlements came with risks. Fires in squatter houses have always been a concern and helped drive the British colonial government to resettle residents into public housing.

Officially, the public housing policy is presented as help for the fire victims in the squatter villages. But research suggests other political factors were at play, Fung said. One such factor was the British government's desire to prevent interference from mainland China, which wanted to send a delegation to help displaced villagers after a fire in the early 1950s.

“Now we see how the landscape of Hong Kong is tremendously shaped by the building of public housing, where people locate in different areas and build their own lives,” he said.

In Cha Kwo Ling, Lo, the long-time villager, expressed reservations about moving into a high-rise building.

He has built a lifetime of memories in the village, from being part of its Qilin dance team from a young age to serving on the volunteer fire prevention team. He worked as a driver in the village’s quarry, which had supplied stones to build the city’s top court and to neighboring Guangzhou and Southeast Asia.

“I’ve grown accustomed to living here,” he said.

Even after being forced to relocate due to fires, some former residents found themselves drawn back to the village, maintaining their ties to the community.

Teoh Bee Hua, a Malaysian who moved to Cha Kwo Ling after marrying a villager in 1973, kept operating her grocery shop there even though she no longer lives in the village after a fire. Teoh, in her 70s, recalled she used to chat with her neighbors and held barbecue and hotpot gatherings with them, saying “those were the happy days."

She said she will shut her shop when the relocation time comes, marking the end of an era as she retires for good.

“There’s nothing you can do. We will surely part. There are gatherings and partings in life. That’s how life is,” she said.

Associated Press news assistant Renee Tsang contributed to this report.

FILE- Government built refugee settlement projects in Hong Kong, Sept. 1, 1960. (AP Photo/W, File)

FILE- View of Hong Kong 's hillsides with "squatter" huts of refugees in this photo from 1959. (AP Photo/Fred Waters, File)

FILE- Perched high on a hill, a shiny new apartment house looks down upon a settlement of squatters' huts in the British crown colony of Hong Kong on May 16, 1956. (AP Photo/File)

A villager tends her store at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A general view of the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping walks past squatter registration info written on the walls of a house in Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

The flags of China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) are flown at the entrance to the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Letterboxes stuffed with mails are seen at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A general view of the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A elderly villager attends to his laundry at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A villager walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Laundry are hung to dry at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping attends to his laundry at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong poses for a photo as she tends to her vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong dries her harvested vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong dries her harvested vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Chan Shun-hong tends to her vegetables at the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A villager walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Teoh Bee Hua, a Malaysian who moved to Cha Kwo Ling after marrying a villager in 1973, poses for a photo at her grocery shop in the Cha Kwo Ling Village in Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. She has kept operating her grocery shop there even though she no longer lives in the village after a fire. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A villager walks through the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping holds up an old black and white photo where he can be seen in the second from top right at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping carries the head prop that's used in the traditional "Qilin" Dance at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Villager Lo Yuet-ping cleans the head prop that's used in the traditional "Qilin" Dance at the Cha Kwo Ling village in east Kowloon, Hong Kong, Sunday, Aug. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

TikTok faced off with the U.S. government in federal court on Monday, arguing a law that could ban the platform in a few short months is unconstitutional while the Justice Department said it is needed to eliminate a national security risk posed by the popular social media company.

In a more than two hour appearance before a panel of three judges at a federal appeals court in Washington, attorneys for the two sides - and content creators - were pressed on their best arguments for and against the law that forces the two companies to break ties by mid-January or lose one of their biggest markets in the world.

Andrew Pincus, a veteran attorney representing the two companies, argued in court that the law unfairly targets the company and runs afoul of the First Amendment because TikTok Inc. - the U.S. arm of TikTok - is an American entity. After his remarks, another attorney representing content creators who are also challenging the law argued it violates the rights of U.S. speakers and is akin to prohibiting Americans from publishing on foreign-owned media outlets, such as Politico, Al Jazeera or Spotify.

“The law before this court is unprecedented and its effect would be staggering,” Pincus said, adding the act would impose speech limitations based on future risks.

The measure, signed by President Joe Biden in April, was the culmination of a years-long saga in Washington over the short-form video-sharing app, which the government sees as a national security threat due to its connections to China.

The U.S. has said it's concerned about TikTok collecting vast swaths of user data, including sensitive information on viewing habits, that could fall into the hands of the Chinese government through coercion. Officials have also warned the proprietary algorithm that fuels what users see on the app is vulnerable to manipulation by Chinese authorities, who can use it to shape content on the platform in a way that’s difficult to detect.

Daniel Tenny, an attorney for the Justice Department, acknowledged in court that data collection is useful for many companies for commercial purposes, such as target advertisements or tailoring videos to users' interests.

“The problem is that same data is extremely valuable to a foreign adversary trying to compromise the security of the United States,” he said.

Pincus, the attorney for TikTok, said Congress should have erred on the side of disclosing any potential propaganda on the platform instead of pursuing a divesture-or-ban approach, which the two companies have maintained will only lead to a ban. He also said statements from lawmakers before the law was passed shows they were motivated by the propaganda they perceived to be on TikTok, namely an imbalance between pro-Palestinian and pro-Israel content on the platform during the war in Gaza.

But the panel - composed of two Republican and one Democrat appointed judges - expressed some skepticism, pressing the attorneys on TikTok's side if they believe the government has any leeway to curtail an influential media company controlled by a foreign entity in an adversarial nation. In parts of their questions about TikTok's foreign ownership, the judges asked if the arguments presented would apply in cases where the U.S. is engaged in war.

Judge Neomi Rao, who was appointed by former President Donald Trump, said the creators suing over the law could continue speaking on TikTok if the company is sold or if they choose to post content on other platforms. But Jeffrey Fisher, their attorney, argued there are not “interchangeable mediums” for them because TikTok — which has 170 million U.S. users — is unique in its look and feel, and the types of audiences it allows them to reach.

Paul Tran, one of the content creators who is suing the government, told reporters outside the courthouse on Monday that a skincare company him and his wife founded in 2018 was struggling until they started making TikTok videos three years ago. He said they had tried to market their products through traditional advertising and other social media apps. But the TikTok videos were the only thing that drove views, helping them get enough orders to sell out of products and even appear on TV shows.

“TikTok truly invigorated our company and saved it from collapse,” Tran said.

Currently, he noted the company - Love and Pebble - sells more than 90% of its products over TikTok, which is covering the legal fees for the creator lawsuit.

In the second half of the hearing, the panel pressed the Justice Department on First Amendment challenges to the law.

Judge Sri Srinivasan, the chief judge on the court who was appointed by former President Barack Obama, said efforts to stem content manipulation through government action does set off alarm bells and impact people who receive speech on TikTok. Tenny, the attorney for the DOJ, responded by saying the law doesn't target TikTok users or creators and that any impact on them is only indirect.

For its part, TikTok has repeatedly said it does not share U.S. user data with the Chinese government and that concerns the government has raised have never been substantiated. In their lawsuit, TikTok and ByteDance have also claimed divestment is not possible. And even if it was, they say TikTok would be reduced to a shell of its former self because it would be stripped of the technology that powers it.

Though the government’s primary reasoning for the law is public, significant portions of its court filings includes information that's redacted.

In one of the redacted statements submitted in late July, the Justice Department claimed TikTok took direction from the Chinese government about content on its platform, without disclosing additional details about when or why those incidents occurred. Casey Blackburn, a senior U.S. intelligence official, wrote in a legal statement that ByteDance and TikTok “have taken action in response” to Chinese government demands “to censor content outside of China.” Though the intelligence community had “no information” that this has happened on the platform operated by TikTok in the U.S., Blackburn said it may occur.

But the companies have argued the government could have taken a more tailored approach to resolve its concerns.

During high-stakes negotiations with the Biden administration more than two years ago, TikTok presented the government with a draft 90-page agreement that allows a third party to monitor the platform’s algorithm, content moderation practices and other programming. But it said a deal was not reached because government officials essentially walked away from the negotiating table in August 2022.

Justice officials have argued complying with the draft agreement is impossible, or would require extensive resources, due to the size and the technical complexity of the platform. They say the only thing that would resolve the government’s concerns is severing the ties between TikTok and ByteDance.

FILE - The TikTok Inc. building is seen in Culver City, Calif., on March 17, 2023. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)