TALLINN, Estonia (AP) — More than a half-million Belarusians have fled their country in the past four years as the authoritarian government launched a harsh crackdown on its political opponents. Some of them, however, are discovering that they can't escape intimidation and threats in their new lives abroad.

Dziana Maiseyenka, 28, was detained without warning while crossing the border from Armenia to Georgia, where she had taken refuge from Belarus a year ago to escape what she called “the nightmare at home.”

Click to Gallery

FILE - Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, center, holds a portrait of her jailed husband, Siarhei Tsikhanouski, at a protest outside the Belarus Embassy, in Vilnius, Lithuania, on March 8, 2024, demanding freedom for political prisoners. (AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis, File)

Andrei Hniot, a filmmaker and a prominent critic of the authoritarian government in Belarus, stands in his apartment in Belgrade, Serbia, where he is under house arrest on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic)

A tracking device is seen on the leg of Andrei Hniot, a filmmaker and a prominent critic of the authoritarian government in Belarus, currently under house arrest in Belgrade, Serbia, on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic)

Andrei Hniot, a filmmaker and a prominent critic of the authoritarian government in Belarus, poses for a portrait in his apartment while under house arrest in Belgrade, Serbia, on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic)

FILE – Former Belarusian athlete Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, who sought political asylum in Poland three years ago, talks with teammates following their women's 4x100-meter relay heat at the Paris Olympics, on Aug. 8, 2024, in Saint-Denis, France. (AP Photo/Petr David Josek, File)

FILE - Belarusian dissident Pavel Latushka, a prominent opposition figure in exile, talks on the phone in Warsaw, Poland, on Aug. 2, 2021. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski, File)

FILE - Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, center, holds a portrait of her jailed husband, Siarhei Tsikhanouski, at a protest outside the Belarus Embassy, in Vilnius, Lithuania, on March 8, 2024, demanding freedom for political prisoners. (AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis, File)

FILE - Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko attends a meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia, on May 8, 2024. (Evgenia Novozhenina/Pool Photo via AP, File)

CORRECTS THE NAME OF SOURCE - Dziana Maiseyenka, 28, who fled Belarus a year ago to escape a crackdown on government opponents, poses for a picture in Yerevan, Armenia, Saturday, Sept. 7, 2024. (Hayk Baghdasaryan/Photolure via AP)

CORRECTS THE NAME OF SOURCE - Dziana Maiseyenka, 28, walks in a street in Yerevan, Armenia, Saturday, Sept. 7, 2024, after being denied entry to neighboring Georgia because an arrest warrant had been issued for her by authorities in Minsk. (Hayk Baghdasaryan/Photolure via AP)

Authorities in Minsk, she was told, had issued an international arrest warrant against her on charges of “organizing mass unrest.”

She knows what a return to Belarus will mean: Her father was imprisoned for nearly three years on similar charges. When he was released last year, he was promptly arrested again.

As hard-line President Alexander Lukashenko seeks his seventh term next year to extend his three-decade rule, opposition leaders in exile say he is ramping up the pressure on Belarusians who moved abroad. The aim is to avoid a repeat of the mass protests that broke out around the 2020 election by quashing any opposition support from abroad.

Months of large demonstrations over that widely denounced balloting resulted in more than 65,000 people arrested over the last four years, with many of them severely beaten, according to the Belarusian human rights group Viasna. Its Nobel Peace Prize-winning founder, Ales Bialiatski, is among those imprisoned.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who was Lukashenko’s main challenger in 2020 before fleeing to Lithuania the day after the election, says Belarus has launched a systematic campaign against dissidents abroad.

“Ahead of the 2025 campaign, repressions against Belarusians abroad will most likely only intensify as the regime tries to intimidate those who call for increased international sanctions and nonrecognition of Lukashenko’s legitimacy,” she said in an interview with The Associated Press.

Tsikhanouskaya said her office gets hundreds of requests a month from Belarusians abroad who say criminal cases have been opened against them in their homeland, and it is intervening in at least 15 countries where extradition requests have been made. Other emigres complain their identity documents have been invalidated by the government in Minsk or that relatives at home have come under pressure.

Pavel Latushka, a prominent opposition figure in exile in Poland, says he's received threats, which Polish authorities are investigating, and his website came under a cyberattack that he blames on Lukashenko's government.

Belarusian sprinter Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, who sought political asylum in Poland three years ago after the Tokyo Olympics, also said she had received threatening messages in Warsaw.

One said "they would rip my stomach open if I went outside,” Tsimanouskaya told AP at the Paris Olympics.

In another, separate instance, she said she noticed “two men were constantly following me” in her neighborhood. "They went outside when I went outside. This was not some kind of coincidence," Tsimanouskaya said, adding that it ended after she reported it to police. At the Paris Games, Polish team officials advised her to keep to the more secure athletes village whenever possible.

Viasna representative Pavel Sapelka said the Belarus KGB is infiltrating the diaspora, organizing surveillance and taking video of large protests abroad, and then initiating hundreds of criminal cases at home.

“Official Minsk has begun sending out extradition requests en masse, and the logic here is very simple -- even if they manage to bring back only a few from abroad, everyone will be scared,” he said.

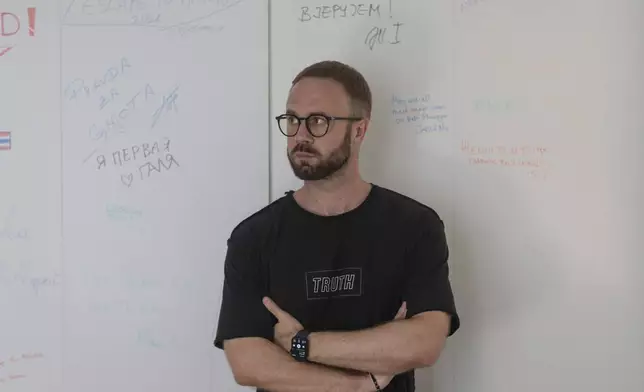

Independent director Andrei Hniot, a Lukashenko critic who made films about the Minsk protests, was arrested last year at Belgrade’s airport on an Interpol warrant at the request of Belarusian authorities for alleged tax evasion. A Serbian court in June ordered his extradition, but European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen intervened.

In a letter to the Belarusian opposition office, she said Serbian authorities were told Hniot’s case “was politically motivated” and he “would face reprisals” if returned to his homeland.

“The route to Belarus is a direct road to prison,” Hniot told AP from Belgrade, where he's under house arrest while awaiting a final ruling.

In August, two anti-Lukashenko activists were deported from Sweden after being refused political asylum. The mother and son who had participated in protests in Belarus were taken by Swedish authorities to the Lithuania-Belarus frontier and handed over to Belarusian border guards. The son was detained at the border.

“Belarusians need European solidarity not in words but in deeds," said Zmitser Vaserman, who represents a Belarusian exile group in Sweden, urging a "European moratorium on the deportation of Belarusian citizens who are persecuted for political reasons.”

To protect the interests of Belarusians abroad, the opposition has created “people’s embassies” in 24 countries, including in EU member states, the U.K., Canada, Australia and Brazil.

Belarusian authorities responded by declaring these “people’s embassies” to be extremist groups; cooperation with them is punishable by up to seven years in prison and confiscation of property. In the spring, authorities carried out a wave of searches and arrests inside Belarus, initiating hundreds of criminal cases at home and abroad.

“Extremist groups have launched information campaigns to discredit our country in the eyes of Western politicians,” said Siarhei Kabakovich, spokesman for the Investigative Committee of Belarus. “The pseudo-embassies are trying to damage the national security of Belarus and are carrying out measures to isolate diplomatic missions of the Foreign Ministry system and block any contacts between foreign citizens, organizations and governments with Belarusian diplomats.”

In Vilnius, where opposition leader Tsikhanouskaya is based, several Belarusian institutions were attacked this month. Windows were broken at a Belarusian Orthodox church and a center of Belarusian culture, and obscene messages were left near a refugee shelter.

Lithuania's Foreign Ministry in a statement on X condemned “the acts of vandalism against the Belarusian community carried out according to the KGB playbook” and vowed to punish those responsible.

Tsikhanouskaya called for an investigation, blaming “the Lukashenko regime, which is constantly trying to create an atmosphere of fear and hate in Belarusian society.”

Belarus now requires its citizens to renew their passports inside the country. That leaves many exiles in a bind, fearing prosecution if they return home to get new documents.

Of particular concern are children born abroad to parents who cannot return to Belarus to get documents confirming their citizenship, said Anaïs Marin, the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights in Belarus, because "this may lead to loss of proof of citizenship and, potentially, to statelessness.”

Many Belarusians returning home have been arrested at the border, said Tsikhanouskaya. Some record video confessions of repentance, which are widely believed to be coerced.

Katsiaryna Mendryk, a student at the University of Warsaw who was arrested in August, said in a subsequent video confession that she “really regrets participating in extremist activities.” She goes on trial this month, facing up to seven years in prison.

Maiseyenka, the woman detained at the Georgia-Armenia border, spent five days in limbo before returning safely to the Georgian capital of Tbilisi. Tsikhanouskaya's office intervened on her behalf, and Armenia decided not to extradite her, she told AP.

Maiseyenka said she was “a lucky exception” but "realized with horror how dangerous it is to be Belarusian.”

“Lukashenko is showing that he can hang the fate of any citizen by a thread,” she said. “This means that a Belarusian anywhere in the world needs to be prepared for unpleasant surprises.”

Associated Press writer James Ellingworth contributed to this report.

Andrei Hniot, a filmmaker and a prominent critic of the authoritarian government in Belarus, stands in his apartment in Belgrade, Serbia, where he is under house arrest on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic)

A tracking device is seen on the leg of Andrei Hniot, a filmmaker and a prominent critic of the authoritarian government in Belarus, currently under house arrest in Belgrade, Serbia, on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic)

Andrei Hniot, a filmmaker and a prominent critic of the authoritarian government in Belarus, poses for a portrait in his apartment while under house arrest in Belgrade, Serbia, on Friday, Sept. 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Marko Drobnjakovic)

FILE – Former Belarusian athlete Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, who sought political asylum in Poland three years ago, talks with teammates following their women's 4x100-meter relay heat at the Paris Olympics, on Aug. 8, 2024, in Saint-Denis, France. (AP Photo/Petr David Josek, File)

FILE - Belarusian dissident Pavel Latushka, a prominent opposition figure in exile, talks on the phone in Warsaw, Poland, on Aug. 2, 2021. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski, File)

FILE - Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, center, holds a portrait of her jailed husband, Siarhei Tsikhanouski, at a protest outside the Belarus Embassy, in Vilnius, Lithuania, on March 8, 2024, demanding freedom for political prisoners. (AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis, File)

FILE - Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko attends a meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia, on May 8, 2024. (Evgenia Novozhenina/Pool Photo via AP, File)

CORRECTS THE NAME OF SOURCE - Dziana Maiseyenka, 28, who fled Belarus a year ago to escape a crackdown on government opponents, poses for a picture in Yerevan, Armenia, Saturday, Sept. 7, 2024. (Hayk Baghdasaryan/Photolure via AP)

CORRECTS THE NAME OF SOURCE - Dziana Maiseyenka, 28, walks in a street in Yerevan, Armenia, Saturday, Sept. 7, 2024, after being denied entry to neighboring Georgia because an arrest warrant had been issued for her by authorities in Minsk. (Hayk Baghdasaryan/Photolure via AP)

MEXICO CITY (AP) — All of a sudden, women contacting one of the biggest sources of information about abortion in Mexico through the encrypted messaging app WhatsApp were met with silence.

The nongovernmental organization’s business account had been blocked. Weeks later, a similar digital blackout struck a collective in Colombia.

Across the Americas, organizations that guide women seeking abortions in various countries are raising alarm, decrying what they see as a new wave of censorship on platforms owned by tech giant Meta — even in countries where abortion is decriminalized. The organizations believe this is due to a combination of changes to Meta policies and attacks by anti-abortion groups that denounce their content.

While this also occurs on Instagram and Facebook, the blocking of organizations’ verified WhatsApp business accounts, which they use to communicate with people seeking help, has been particularly disruptive. These accounts are crucial for communicating with people seeking help, and their blockage has significantly complicated daily interactions between women and support providers.

Meta usually attributes its content blocking to policy violations, though it has acknowledged occasional mistakes. Since January, Meta changed the way it moderates content, now relying on user-generated notes “to allow more speech and reduce enforcement mistakes.” U.S. President Donald Trump has said the changes were “probably” made in response to his threats over what conservatives considered a liberal bias in fact-checking.

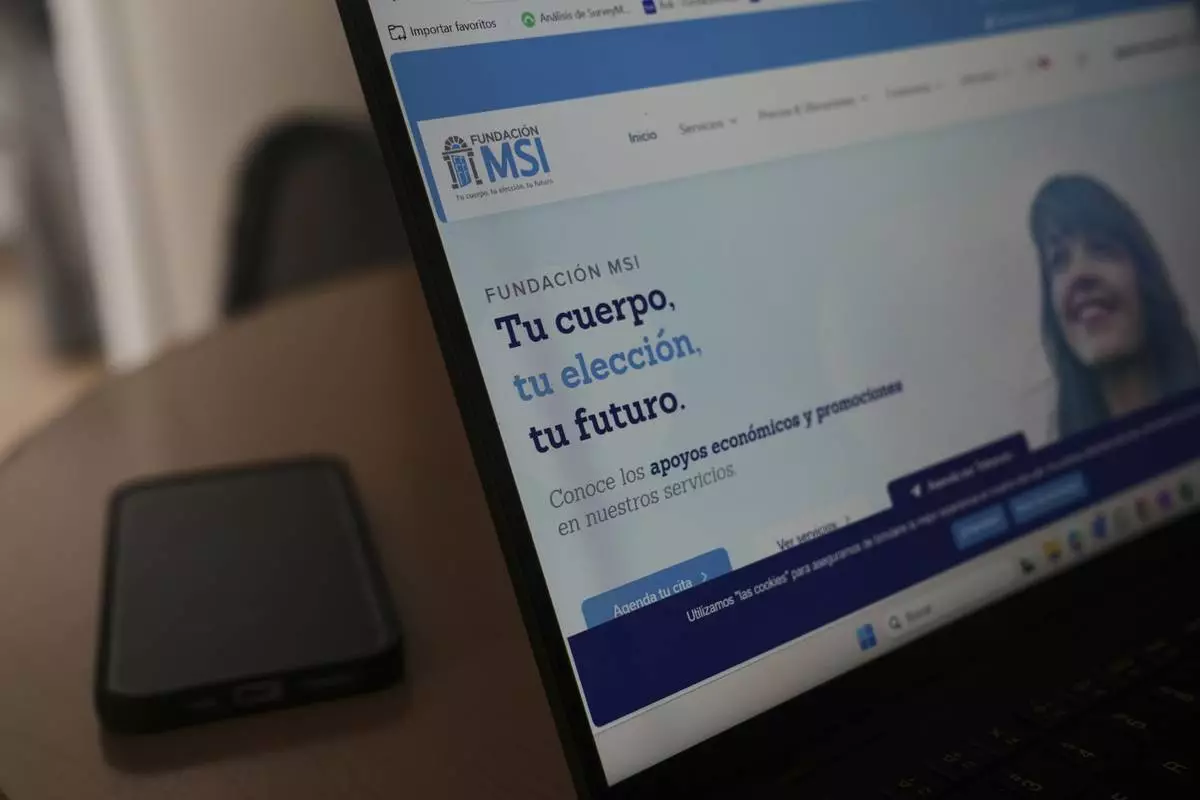

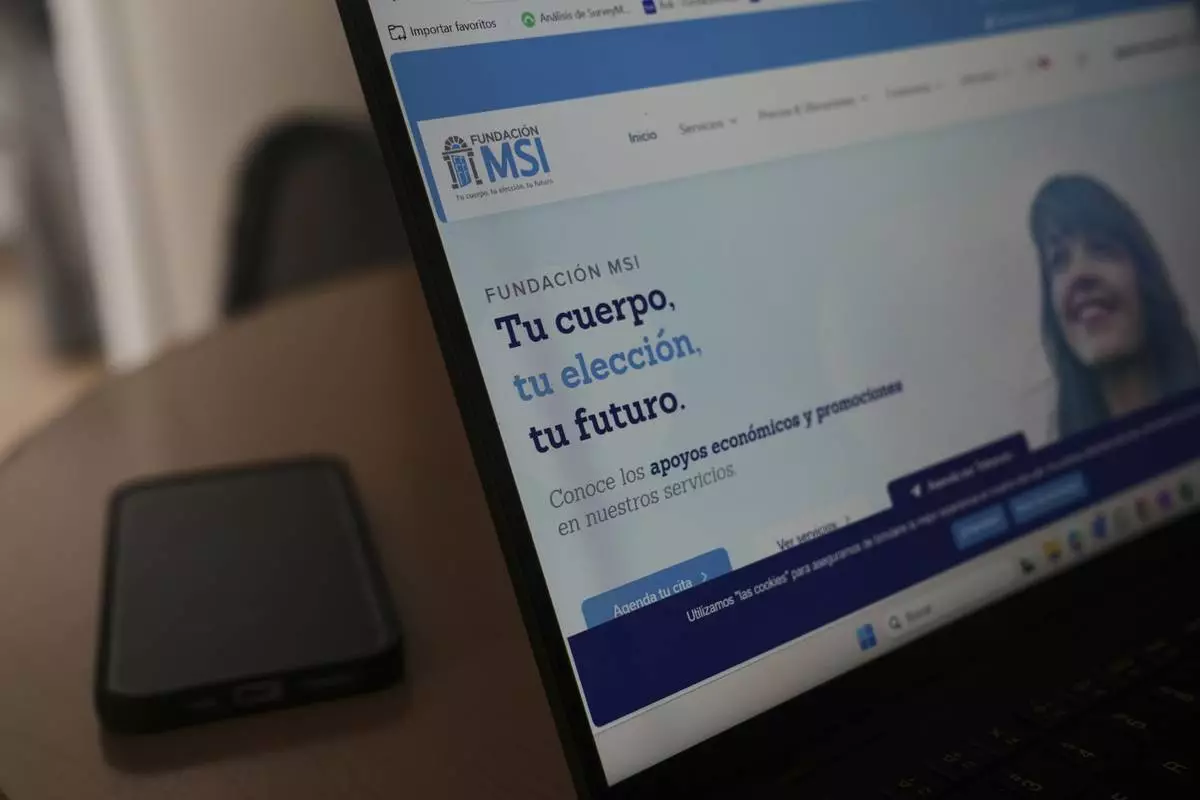

Among the organizations whose WhatsApp business accounts were suspended is the MSI Foundation (part of MSI Reproductive Choices, formerly Marie Stopes) a network working in Mexico for 25 years. Its account was suspended in February, and the Colombian group Oriéntame, or Guide Me, which has worked in women's health in Colombia for decades, was labeled by Instagram as “dangerous.”

While conservatives cheered the change in Meta moderation policies, organizations helping women who seek abortions say that, even if they just apply in the U.S., they often result in over-enforcement, likely driven by Artificial Intelligence, which disproportionately flags or removes their posts — obstacles that have increased since the start of the Trump administration.

“It is not always intentional censorship, but the outcome is still more censorship for us and our partners,” said Martha Dimitratou, cofounder of Repro Uncensored, an organization that monitors digital suppression of reproductive health content.

In additional comments on Thursday, Meta rejected any link between the groups’ experiences and its policy changes.

“Our policies and enforcement regarding abortion medication-related content have not changed recently and were not part of the content moderation changes,” Meta said in a statement.

“From one day to the next they blocked communication between our users and women who need first-hand information” to address doubts or look for medical follow-up with MSI, said Araceli López-Nava, the organization’s Latin America director.

In the days after the suspension, appointments dropped 80%

López Nava said that MSI had previously faced issues with regular WhatsApp numbers, because it’s easy to file complaints. So, the organization thought it would be different with a business account, which gives them a platform to manage the thousands of messages they receive every month.

That wasn't the case. After an initial suspension, MSI's WhatsApp business account was permanently suspended two weeks later. The reason cited in Meta’s notification? “Sending spam.”

“The argument is that they’ve received complaints, but from whom?” López-Nava asked. She said the organization can’t be accused of sending spam because they only answer those who contact them and provide information in line with Mexican law. Abortion is decriminalized in Mexico at the federal level and in the majority of its 32 states.

“It looks like an orchestrated strategy to us,” López-Nava said. “And not necessarily by Meta."

Dimitratou, who is also digital strategist for Canada-based Women on Web and the U.S.-based Plan C, said cases of blocked content have increased since Trump’s election, not only in the U.S., but around the world, likely driven by anti-abortion groups.

Conservative or religious groups have a history of attempting to leverage technology companies to obstruct abortion supporters’ efforts, but the anonymity of app reporting prevents organizations from proving who is behind it.

That is why MSI and an ally NGO, Women’s Link Worldwide, have asked Meta to implement transparent mechanisms to be able to appeal the company’s decisions and to respect international human rights standards. They have not received a response.

A Meta spokesperson told The Associated Press that MSI's WhatsApp business account was blocked for valid reasons, saying that organizations receiving numerous negative comments receive warnings before suspension. Meta declined to provide details about the nature of the negative comments or comment on whether they could be coordinated by anti-abortion groups aiming to paralyze MSI.

The Instagram accounts of Women on Web United States and Women on Web Latin America were suspended right after the U.S. presidential election in November, though they were later reinstated. Dimitratou said that Meta has also limited the organization’s ability to place ads on accounts in Latin America, South Korea and West Africa.

Repro Uncensored has documented at least 60 instances of similar digital censorship since January. The most recent occurred this week, when Thailand's TamTang Group said that Facebook had accused them of violating rules on selling medicines simply for sharing information about free abortion pills provided by the Thai government.

A 2025 report by the California-based Center for Intimacy Justice, based on a survey of 159 nonprofits worldwide, found that major tech platforms were removing ads and content related to abortion and other women’s sexual and reproductive health issues like menopause.

When asked about the report, Meta downplayed its findings, noting that it was based on a small number of examples.

Tech companies often cite policies against explicit or inappropriate sexual content or the advertisement of unsafe substances, such as abortion pills, even though the World Health Organization has said they’re safe.

In April, months after Meta announced changes to ensure greater freedom of expression, Oriéntame, the Colombian collective that offers reproductive health services, posted on Instagram a drawing of a heart and the phrase “Abort without pain.” The post was blocked with the explanation: “Dangerous people and organizations, photo removed.”

While Colombia legalized abortion in 2022, Oriéntame experienced censorship of at least 14 of their posts on Instagram in April 2025. That same month, their WhatsApp business account was suspended, said Tatiana Martínez, who manages their social media. Although the WhatsApp account was restored after a week, they worry it could happen again.

A Meta spokesperson said this week that the Instagram posts were mistakenly taken down and not the result of a change in its content standards.

Oriéntame director María Vivas says the organization has been battling Google for years over online content limitations. The tech giant said in a message to the AP that it only restricts content when it violates policies. But Google keeps Colombia on the list of countries with restrictions on abortion ads — even though abortion was decriminalized there in 2022.

As for their problems with Meta, Vivas said they started in late 2024, when the company started to make some data management adjustments.

Taking legal action against tech giants, when each country has its own laws, is complicated. As a result, affected organizations have turned to creative strategies, like operating multiple backup accounts, having a substitute ready when one is blocked and reformulating language in posts to avoid censorship triggers.

“It feels like Meta is our boss,” Vivas joked about the ongoing struggle with the tech giant over the basic right to provide health information. “We live to respond to Meta, to adapt ourselves to Meta,” she said. “That's absurd.”

AP journalist Maria Cheng contributed to this report from New York.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

A computer monitor shows the splash page of the MSI Foundation website with a message that reads in Spanish: "Your body, your choice, your future", during a tour of the foundation, a non-governmental agency that offers information and help to women seeking abortions, in Mexico City, Thursday, May 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

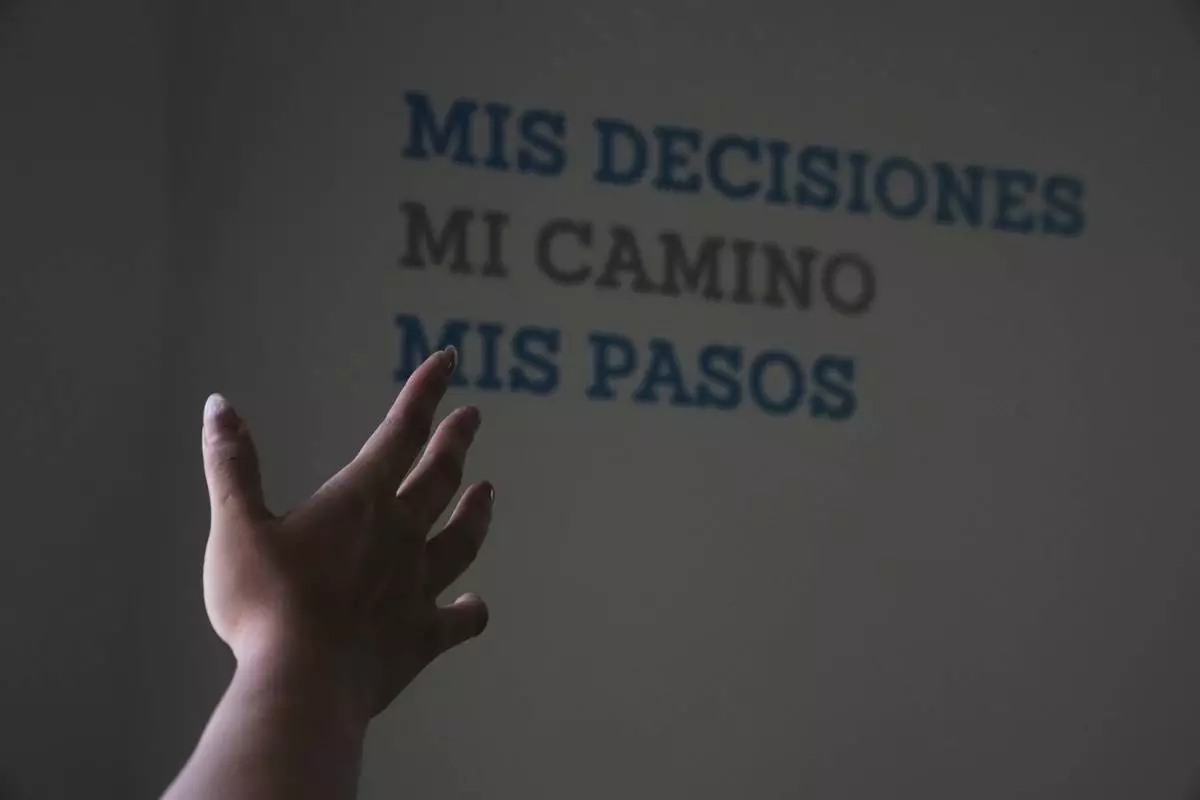

A health worker gives a tour of the MSI Foundation, an organization that offers information and help to women seeking abortions, in Mexico City, Thursday, May 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

A health worker gestures towards a message that reads in Spanish; "My decisions, my road, my steps" during a tour of the MSI Foundation, an organization that offers information and help to women seeking abortions, in Mexico City, Thursday, May 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)

A health worker gives a tour of the MSI Foundation, an organization that offers information and help to women seeking abortions, in Mexico City, Thursday, May 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Marco Ugarte)