BALTIMORE (AP) — Investigators working to pinpoint the cause of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse discovered a loose cable that could have caused electrical issues on the Dali, the massive cargo ship that lost power and disastrously veered off course before striking the bridge.

When disconnected, the problematic cable triggered an electrical blackout on the ship similar to what happened as it approached the bridge on March 26, according to new documents released Wednesday by the National Transportation Safety Board.

The documents don’t include any analysis or conclusions, which will be released later in the board’s final report. A spokesperson for the board declined to comment as the investigation is ongoing.

The Dali was leaving Baltimore bound for Sri Lanka when its steering failed because of the power loss. It crashed into one of the bridge’s supporting columns, destroying the 1.6-mile span and killing six members of a roadwork crew.

Safety investigators released a preliminary report earlier this year that documented a series of power issues on the ship before and after its departure from Baltimore. But the new records offer more details about how its electrical system may have failed in the critical moments leading up to the deadly disaster.

The Dali first experienced a power outage when it was still docked in Baltimore. That was after a crew member mistakenly closed an exhaust damper while conducting maintenance, causing one of the ship’s diesel engines to stall, according to the earlier report. Crew members then made changes to the ship’s electrical configuration, switching from one transformer and breaker system — which had been in use for several months — to a second that was active upon its departure.

That second transformer and breaker system is where investigators found the loose cable, according to investigative reports.

Investigators also removed an electrical component from the same system for additional testing, according to a supplemental report released in June. They removed what is called a terminal block, which is used to connect electrical wires.

Engineers from Hyundai, the manufacturer of the ship’s electrical system, said the loose cable could create an open circuit and cause a breaker to open, according to a 41-page report detailing tests completed on the Dali in the weeks after the collapse. The engineers disconnected the cable as part of a simulation, which resulted in a blackout on the ship.

Hyundai sent engineers from its headquarters in South Korea to help with the investigation in April.

The new documents also included various certificates issued after inspections of the Dali pertaining to its general condition and compliance with maritime safety regulations.

“It’s pretty clear that they think they’ve found an issue that could cause a blackout,” said Tom Roth-Roffy, a former National Transportation Safety Board investigator who focused on maritime investigations. He said the loose cable was in a critical place within the electrical system.

He also noted that investigators have clearly taken a thorough approach and documented their findings well. The new documents suggest they found very few other problems as they combed through the various systems and machinery aboard the Dali.

In terms of whether the loose connection suggests inadequate maintenance of the ship or other problems with the crew, Roth-Roffy said it seems like a toss-up. Checking hundreds or thousands of wires is a tedious and time-consuming process, he said, and there are any number of factors that could cause connections to loosen over time, including the constant vibrations on a ship.

“To say that this should have been detected is probably true but somewhat unrealistic,” he said. “But the ship’s crew has ultimate responsibility for the proper maintenance and operation of the ship.”

The Dali left Baltimore for Virginia in late June. It was scheduled to undergo repairs there, and local media reported last week that it will sail to China, likely sometime later this month.

Associated Press writer Ben Finley contributed to this report.

FILE - In this aerial image released by the Maryland National Guard, the cargo ship Dali is stuck under part of the structure of the Francis Scott Key Bridge after the ship hit the bridge, March 26, 2024, in Baltimore. (Maryland National Guard via AP, File)

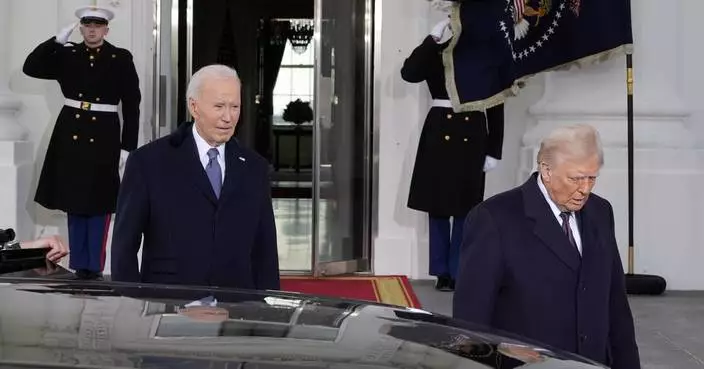

WASHINGTON (AP) — U.S. President Donald Trump used one of the flurry of executive actions that he issued on his first day back in the White House to begin the process of withdrawing the U.S. from the World Health Organization for the second time in less than five years — a move many scientists fear could roll back decadeslong gains made in fighting infectious diseases like AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

Experts have also cautioned that withdrawing from the organization could weaken the world’s defenses against dangerous new outbreaks capable of triggering pandemics.

Here’s a look at what Trump’s decision means:

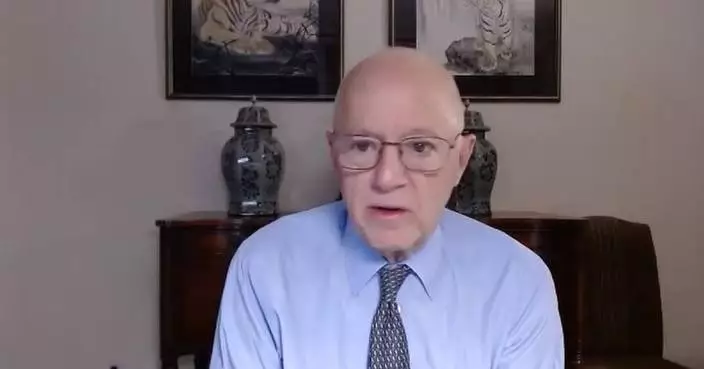

During the first Oval Office appearance of his second term, Trump signed an executive order detailing how the withdrawal process might begin.

“Ooh," Trump exclaimed as he was handed the action to sign. "That’s a big one!”

His move calls for pausing the future transfer of U.S. government funds to the organization, recalling and reassigning federal personnel and contractors working with WHO and calls on officials to “identify credible and transparent United States and international partners to assume necessary activities previously undertaken by” WHO.

This isn’t the first time Trump has tried to sever ties with WHO. In July 2020, several months after WHO declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic and as cases surged globally, Trump’s administration officially notified U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres that the U.S. was planning to pull out of WHO, suspending funding to the agency.

President Joe Biden reversed Trump’s decision on his first day in office in January 2021 — only to have Trump essentially revive it on his first day back at the White House.

It is the U.N.’s specialized health agency and is mandated to coordinate the world’s response to global health threats, including outbreaks of mpox, Ebola and polio. It also provides technical assistance to poorer countries, helps distribute scarce vaccines, supplies and treatments and sets guidelines for hundreds of health conditions, including mental health and cancer.

“A U.S. withdrawal from WHO would make the world far less healthy and safe,” said Lawrence Gostin, director of the WHO Collaborating Center on Global Health Law at Georgetown University. He said in an email that losing American resources would devastate WHO's global surveillance and epidemic response efforts.

Dr. Tom Frieden, a former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said Trump's move "surrenders our role as a global health leader and silences America’s voice in critical decisions affecting global health security.”

“We cannot make WHO more effective by walking away from it,” Frieden said in a statement. “This decision weakens America’s influence and increases the risk of a deadly pandemic.”

Yes, as long as he gets the approval of Congress and the U.S. meets its financial obligations to WHO for the current fiscal year. The U.S. joined WHO via a 1948 joint resolution passed by both chambers of Congress, which has subsequently been supported by all administrations. The resolution requires the U.S. to provide a one-year notice period should it decide to leave WHO.

It’s extremely bad. The U.S. has historically been among WHO’s biggest donors, providing the U.N. health agency not only with hundreds of millions of dollars, but also hundreds of staffers with specialized public health expertise.

In the last decade, the U.S. has given WHO about $160 million to $815 million every year. WHO’s yearly budget is about $2 billion to $3 billion. Losing U.S. funding could cripple numerous global health initiatives, including the effort to eradicate polio, maternal and child health programs, and research to identify new viral threats.

American agencies that work with WHO would also suffer, including the CDC. Leaving WHO would exclude the U.S. from WHO-coordinated initiatives, like determining the yearly composition of flu vaccines and quick access to critical genetic databases run by WHO, which could stall attempts to produce immunizations and medicines.

At a September campaign rally, Trump said he would “take on the corruption” at WHO and other public health institutions that he said were “dominated” by corporate power and China.

His executive order Monday said the U.S. was withdrawing from WHO “due to the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic that arose out of Wuhan, China and other global health crises” and cited the agency’s “failure to adopt urgently needed reforms” and its “inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states.”

WHO made several costly mistakes during the pandemic, including advising people against wearing masks and asserting that COVID-19 was not airborne. The agency only officially acknowledged last year that the virus is indeed spread in the air.

During its efforts to stop COVID-19, WHO also dealt with the biggest sexual abuse scandal i n its history, when media reports revealed that dozens of Congolese women had been sexually harassed or assaulted by health responders working to contain Ebola. The AP found senior managers were informed of some instances of sexual abuse when they occurred in 2019 but did little to stop them or punish perpetrators.

In a statement Tuesday, WHO said it “regrets” Trump's announcement.

“We hope the United States will reconsider and we look forward to engaging in constructive dialogue to maintain the partnership between the USA and WHO,” the organization said.

“For over seven decades, WHO and the USA have saved countless lives and protected Americans and all people from health threats. Together, we ended smallpox, and together we have brought polio to the brink of eradication,” WHO said.

At a Geneva news briefing on Tuesday, WHO spokesperson Tarik Jasarevic said the U.S. contributed 18% of WHO's budget in 2023, making it the single biggest donor that year. He declined to say what the U.S. withdrawal might mean for WHO.

Cheng reported from Toronto. Geir Moulson in Berlin contributed to this report.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

President Donald Trump signs an executive order withdrawing the U.S. from the World Health Organization in the Oval Office of the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)