NEW YORK (AP) — MrBeast is accused of creating “unsafe” employment conditions, including sexual harassment, and misrepresenting contestants' odds at winning his new Amazon reality show's $5 million grand prize in a lawsuit filed Tuesday by five unnamed participants.

The filing alleges that the multimillion-dollar company behind YouTube's most popular channel failed to provide minimum wages, overtime pay, uninterrupted meal breaks and rest time for competitors — whose “work on the show was the entertainment product” sold by MrBeast.

A spokesperson for MrBeast, whose real name is Jimmy Donaldson, told The Associated Press in an email that he had no comment on the new lawsuit.

Donaldson’s “Beast Games” was touted as the “biggest reality competition." It was supposed to put the North Carolina content creator in front of audiences beyond the YouTube platform where his record 316 million subscribers routinely watch his whimsical challenges that often carry lavish gifts of direct cash.

But its initial Las Vegas shoot began facing criticism before it even wrapped. Donaldson’s companies cast 2,000 people in an initial tryout this July where half could advance to the actual show's filming in Toronto.

Contestants only learned upon their arrival that the Las Vegas pool surpassed 1,000 competitors, according to the lawsuit, which significantly reducing their chances of victory. The lawsuit argues the “false advertising” violated California business laws that prohibit sweepstakes operators from “misrepresenting in any manner the odds of winning any prize."

The five anonymous competitors also said that “limited sustenance" and “insufficient medical staffing” endangered their health.

The filing alleges that production staff created a “toxic” work environment for women who faced “sexual harassment” throughout the contest. Those sections are heavily redacted in an effort to comply with “confidentiality provisions” signed by the competitors, according to a press release from their lawyers.

The lawsuit adds to the complaints — circulated by online influencers in the shoot's immediate aftermath — that an unorganized set had left some contestants injured and lacking in regular access to food and medication. Other participants have told AP they received two light meals each day and MrBeast branded chocolate bars.

MrBeast’s team also faces new accusations they “knowingly misclassified” the contestants’ employment status to the Nevada Film Commission in order to receive a state tax credit for more than $2 million.

Among other forms of relief, the five competitors seek an order that MrBeast institute “workplace reforms” and awards “all wages owed."

Last month, amid several public relations crises, Donaldson ordered a full assessment of his YouTube empire's internal culture and outlined plans to require company-wide sensitivity training.

No more details have been divulged and no date has been publicized for the reality game show's release.

Associated Press coverage of philanthropy and nonprofits receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content. For all of AP’s philanthropy coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/philanthropy.

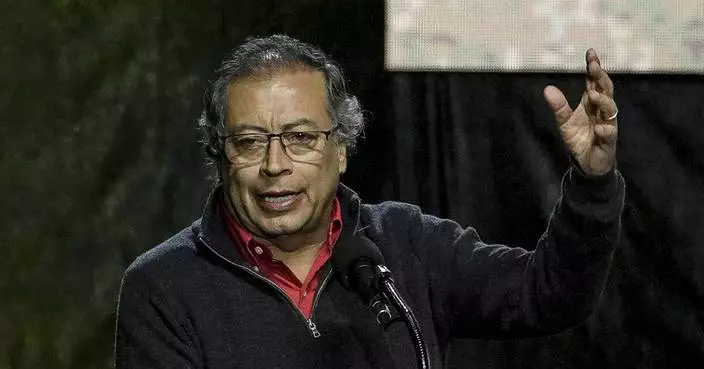

FILE - Jimmy Donaldson, the popular YouTube video maker who goes by MrBeast, wears a Lionel Messi jersey as he stands in a sideline box at the start of an MLS soccer match between Inter Miami and CF Montreal Sunday, March 10, 2024, in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, File)

DUNBARTON, N.H. (AP) — It's harvest time in central New Hampshire, and one farm there appears to have been transplanted from a distant continent.

Farmers balance large crates laden with vegetables on their heads while chatting in Somali and other languages. As the sun burns away the early morning mist, the farmers pick American staples like corn and tomatoes as well as crops they grew up with, like okra and sorrel. Many of the women wear vibrant orange, red and blue fabrics.

Most workers at this Dunbarton farm are refugees who have escaped harrowing wars and persecution. They come from the African nations of Burundi, Rwanda, Somalia and Congo, and they now run their own small businesses, selling their crops to local markets as well as to friends and connections in their ethnic communities. Farming provides them with both an income and a taste of home.

“I like it in the USA. I have my own job," says Somali refugee and farmer Khadija Aliow as she hams it up by sashaying past a reporter, using one hand to steady the crate of crops on her head and the other to give a thumbs-up. "Happy. I’m so happy.”

The farm is owned by a New Hampshire-based nonprofit, the Organization for Refugee and Immigrant Success, which lets the farmers use plots of land and provides them with training and support. The organization runs similar farms in Concord and the nearby town of Boscawen.

In all, 36 people from five African countries, including South Sudan, and the Asian nation of Nepal work on the farms. Many were farmers in their home countries before coming to the U.S. or had previous experience with agriculture, said Tom McGee, a program director with the nonprofit.

“These are farmers who are basically independent business owners, who are working in partnership with our organization to be able to bring this produce to life in this country," he said. "And to have another sense of purpose, and a way that they can bring themselves into the community, and belong. And really participate in the American dream.”

The nonprofit runs a food market in Manchester, where people can buy fresh produce or sign up to have boxes delivered. McGee said there are a few other programs with similar aims scattered throughout the U.S. but that the model remains relatively rare. He said his organization relies on state and federal funding, as well as private donations.

Farmer Sylvain Bukasa said he escaped in 2000 from the decades-long conflict in Congo that has resulted in millions of deaths. He spent six years with his wife and son in a refugee camp in Tanzania before being accepted into the U.S. in 2006.

“I was worried for my safety,” he said. “I decided to just go somewhere where it's a little bit safer.”

Bukasa said he has worked hard since arriving in the U.S. and relishes his new life. But at first he missed the foods he grew up with. He could only find them in specialized markets, where they tended to be expensive and of poor quality.

“Back home we ate more vegetables and less meat,” he said. “When we came here it's more chicken, more pizza, things like that. They taste good, but it's not good for you.”

Bukasa started growing crops on the farm in 2011. The initial plan on the Dunbarton farm was to allow migrants like him to grow traditional crops for themselves and their families. But demand grew, particularly during the pandemic, prompting the farm's evolution into a commercial operation.

For a few of the farmers, the harvest provides their primary income. For most, like Bukasa, it's a side gig. He works fulltime as a service agent for a rental car company and travels whenever he can to tend his plot of just over an acre (0.4 hectares). The biggest challenges are making sure his crops are adequately watered and stopping the weeds from taking over, he said.

Mondays are harvest days, and on a recent Monday, Bukasa listed the crops he was picking: tomatoes, summer squash, zucchini, kale, corn, okra, and the leaves from pumpkins and sorrel — which he and the other migrants call sour-sour because of its taste.

He said there's a surprisingly large Congolese community throughout New England, and they appreciate what he grows.

“It's a hard job, but hard work is good work,” Bukasa said. “It’s fun and it helps people. I like when I satisfy people with the food that they eat."

His dream is to one day buy his own farm with a couple of acres of land, so he can walk out his front door to tend to his crops rather than driving 20 minutes like he does now. A more immediate challenge, he said, is to work on the marketing side of his business.

He's got to the point where he now grows more food than he’s able to sell, and he hates seeing any of it go to waste. One idea is to buy a van, so he can deliver more produce himself.

“You see the competition in there,” he says with a grin, motioning toward the tent where other refugee farmers wash and pack their crops. “See how many farmers are trying to sell their produce.”

Vegetables picked and packaged that morning are loaded onto a delivery truck at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Sylvain Bukasa, a refugee from Democratic Republic of the Congo, chats with a fellow farmer Khamis Khamis, a refugee from Somalia, while harvesting vegetables at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Refugee farmers and program staff sort and package vegetables picked earlier in the morning at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Sylvain Bukasa, a refugee from Democratic Republic of the Congo, takes freshly harvested peppers out of a cleaning tub to be air dried prior to packaging at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A packing platform is sanitized as harvested vegetables begin to arrive at a processing greenhouse at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Khadija Aliow, a refugee from Somali, carries vegetables grown on her plot to be cleaned and packaged at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Sylvain Bukasa, a refugee from Democratic Republic of the Congo, harvests chard at his greenhouse at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A selection of squash, left, and eggplant, right, are stacked after being washed to be packaged for a community share program at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Sylvain Bukasa, a refugee from Democratic Republic of the Congo, smiles while showing the beets grown on his plot at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Alsi Yussuf, a refugee from Somalia, carries freshly picked tomatoes while harvesting vegetables for a community share program at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Alsi Yussuf, a refugee from Somalia, places freshly picked tomatoes from her greenhouse into a carrying box before they are cleaned and packaged at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Farmer Sylvain Bukasa, a refugee from Democratic Republic of the Congo, harvests corn on his plot at Fresh Start Farm, Aug. 19, 2024, in Dunbarton, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)