BOULDER, Colo. (AP) — A mentally ill man carefully amassed guns and ammunition to kill as many people as possible before pursuing and fatally shooting 10 people at a Colorado supermarket in 2021, proving he knew exactly what he was doing, a prosecutor told jurors Friday.

Ahmad Alissa's decision to buy steel-piercing bullets and an optic sight that put a red dot on his victims, before firing multiple times at all but one of his victims shows he acted with intent and was not insane at the time, Assistant District Attorney Ken Kupfner said during closing arguments in Alissa's trial. Everyone who was shot died in the attack.

Alissa, who has schizophrenia, has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity in the attack at the store in the college town of Boulder.

Mental illness is not the same thing as insanity under the law. In Colorado, insanity is defined as having a mental disease so severe it is impossible for a person to tell the difference between right and wrong.

One of Alissa's attorneys, Kathryn Herold, accused prosecutors of trying to appeal to the emotions of jurors by presenting graphic videos of the attack and detailed testimony from victims, even though no one disputed Alissa was the shooter. While two state psychologists appointed by the court found that Alissa was sane at the time of the attack, Herold said they had some reservations. She told jurors that they are the ones who must decide whether he was insane or not.

“When you remove that emotion, it is clear that insanity is the only explanation for this tragedy,” she told them.

Alissa told the state psychologists that he heard voices that were yelling in his head, including what he described as “killing voices” right before the shooting. The psychologists said he never provided details about the voices and whether they said anything specific. However, Alissa did tell them that he thought the voices might stop if he committed a mass shooting.

Herold asked jurors to imagine what it was like to hear voices in your head, yelling in court: “Kill, kill, kill!”

Kupfner told jurors that Alissa fired his first shot at his second victim, Kevin Mahoney, in the parking lot after bracing himself on the hood of a car so he could take better aim with his semi-automatic pistol, which resembled an AR-15 rifle, Kupfner said. Alissa then pursued Mahoney as he tried to get back to the store.

“The defendant was tenacious and he was relentless,” Kupfner said.

During two weeks of trial, the families of those killed saw surveillance and police body camera video of the shooting. Survivors testified about how they fled, helped others to safety and hid. An emergency room doctor crawled onto a shelf and hid among bags of chips.

Herold disputed comments that witnesses said Alissa made during the attack, including “This is fun,” arguing that was out of step with the lack of emotion the experts found when they met with Alissa. She said she thought their brains were trying to make sense of what had happened.

Several members of Alissa’s family, who immigrated to the United States from Syria, testified that starting a few years earlier he had become withdrawn and spoke less. He later began acting paranoid and showed signs of hearing voices, and his condition worsened after he got COVID-19 in late 2020, they said.

Alissa’s mother told the court that she thought her son was “sick.” His father testified that he thought Alissa could be possessed by a djin — an evil spirit — and that his condition was shameful for his family.

His parents and some of Alissa's siblings sat in the court gallery for the first time during the trial on Friday, just a few feet behind him. Alissa fidgeted during the arguments, sometimes appearing to be paying attention to the attorneys and other times appearing distracted and looking around the room.

Relatives of the victims mostly sat on the other side of the courtroom.

Alissa is charged with 10 counts of first-degree murder, multiple counts of attempted murder and other offenses, including having six high-capacity ammunition magazine devices banned in Colorado after previous mass shootings.

Alissa started shooting immediately after getting out of his car at the store on March 22, 2021, killing most of the victims in just over a minute. He killed a police officer who responded to the attack and then surrendered after another officer shot him in the leg.

Alissa got an adrenaline rush and a sense of power from shooting people, Kupfner argued, though prosecutors did not offer any motive for the attack. Kupfner said Alissa first began searching for public places like bars and restaurants in Boulder to attack, before focusing his research on large stores the day before the shooting. Alissa pulled into the first supermarket he encountered as he entered Boulder on his drive from his home in the Denver suburb of Arvada, he said.

The defense did not have to provide any evidence in the case and did not present any experts to say he was insane.

However, the defense pointed out that the state psychologists did not have full confidence in their sanity finding. That was largely because Alissa did not provide them more information about what he was experiencing, even though it could have helped his case.

The experts also said they thought the voices he was hearing played some role in the attack and they did not believe it would have happened if Alissa were not mentally ill.

Trial of man who killed 10 at Colorado supermarket turns to closing arguments

FILE - Ahmad Al Aliwi Alissa, accused of killing 10 people at a Colorado supermarket in March 2021, is led into a courtroom for a hearing, Sept. 7, 2021, in Boulder, Colo. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, Pool, File)

Trial of man who killed 10 at Colorado supermarket turns to closing arguments

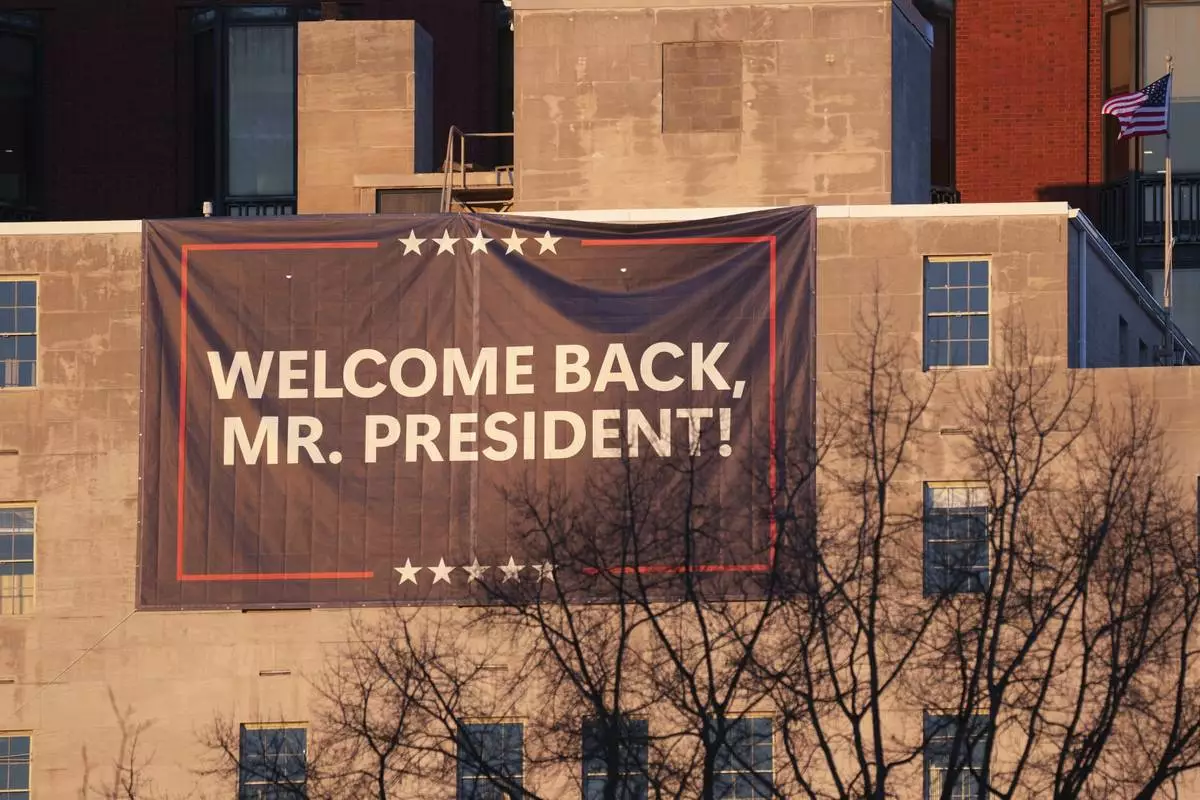

WASHINGTON (AP) — Donald Trump, who overcame impeachments, criminal indictments and a pair of assassination attempts to win another term in the White House, will be sworn in Monday as the 47th U.S. president taking charge as Republicans claim unified control of Washington and set out to reshape the country’s institutions.

Trump’s swearing-in ceremony, moved indoors due to intense cold, will begin at noon ET. But festivities will start earlier when the incoming president arrives for service at St. John’s Episcopal Church.

Here's the latest:

Newt Gingrich, John Boehner and Kevin McCarthy are in the Capitol Rotunda for the inauguration.

The last Democratic Speaker, Nancy Pelosi, has said she is not attending the ceremony.

Arnault, who heads the LVMH fashion empire and is France’s richest man, was sitting a few rows back and to the left of Trump and his wife, Melania, wearing a dark suit and tie.

LVMH’s many brands include Louis Vuitton and Dior, and its influence and Arnault’s wealth make the lowkey billionaire a powerful figure.

LVMH had a stellar year in France last year, especially as a high-profile sponsor of the Paris Olympics. Arnault also was a key donor toward the reconstruction of Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral after its fire in 2019 and attended the monument’s reopening — along with Trump — last December.

It’s become tradition for the outgoing president to write a letter to his successor and leave it in the drawer of the Oval Office desk for the new president to find.

Biden declined to say what he said in the note. Trump wrote Biden a note four years ago.

“This is a day when every American does well to celebrate our democracy and the peaceful transfer of power under the Constitution of the United States,” the former vice president wrote in a post on the social platform X.

“We encourage all our fellow Americans to join us praying for President Trump and Vice President Vance as they assume the awesome responsibility of leading this great Nation,” he added.

Trump and Pence once had a close relationship, but had a falling out when Pence refused to go along with Trump’s unconstitutional scheme to overturn the results of the 2020 election.

Pence ran against Trump in the GOP primary but dropped his bid before any votes were cast.

He has been critical of several of Trump’s proposals for a second term, with a group he runs urging Republican senators not to confirm Robert F. Kennedy to lead the Department of Health and Human Services.

Speaking during a video call with members of Russia’s Security Council just before Trump’s inauguration, Putin said that “we hear the statements from Trump and members of his team about their desire to restore direct contacts with Russia, which were halted through no fault of ours by the outgoing administration.”

“We also hear his statements about the need to do everything to prevent World War III,” Putin said in televised comments. “We certainly welcome such an approach and congratulate the U.S. president-elect on taking office.”

Putin said Moscow is open to discussing a prospective peace settlement in Ukraine, adding it should lead not to a short truce but a lasting peace and take into account Russia’s interests.

The move came after a Hochul spokesperson said last week that flags would remain at half-staff following the death of former President Jimmy Carter.

Flags will be returned to half staff on Tuesday, Hochul said in a statement.

“Regardless of your political views, the American tradition of the peaceful transition of power is something to celebrate,” said Hochul, a Democrat.

They met the Bidens on a gold-trimmed red carpet, exchanging greetings and posing for photos ahead of a private meeting over tea and coffee.

“Welcome home,” Biden said to Trump after the president-elect stepped out of the car.

Biden wrapped his hand around Trump’s upper arm to escort him inside the mansion.

Chesapeake Crab Cake, Greater Omaha Angus Ribeye Steak and wine from Monticello are on the menu for the inaugural luncheon.

That’s according to the joint congressional committee on inauguration ceremonies headed by Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn.

It says the luncheon after the swearing-in ceremony is the 11th to be held at the Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, and will include more than 200 guests including the president, vice president, family, U.S. Supreme Court justices, Cabinet Member-designees and members of Congressional leadership.

For dessert, there’s Minnesota Apple Ice Box Terrine with sour cream ice cream and salted caramel.

Before dawn Monday, ahead of Donald Trump’s inauguration, several dozen people waited in freezing temperatures at a bridge connecting Ciudad Juarez, a Mexican border city, with El Paso, Texas.

They held appointments for CBP One, a program that allows asylum seekers to schedule initial appointments before reaching the border. CBP One has brought nearly 1 million people to the U.S. on two-year permits with eligibility to work and is one of the programs that Trump has said he will end.

Nerves and uncertainty were running high in the line.

Julio González, 35, who came from the violent Mexican state of Michoacan, cried as he considered his circumstances.

“We hope that with Donald Trump’s arrival the application (CBP One) continues,” he said.

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Combined Choirs kicked off the inaugural ceremonies Monday with a musical prelude. The students wore all black with a red scarf embossed with their university logo.

Their voices echoed into the Capitol dome where in just a few hours Trump will be sworn in as the 47th President.

Trump plans on Monday to sign actions to increase domestic oil production including a measure with a focus on Alaska.

That’s according to an incoming administration official who spoke on condition of anonymity under terms set by the transition team in a phone call with reporters.

Trump also plans to sign a memorandum that seeks an all-of-government approach to bringing down inflation.

The incoming official declined to provide specifics, but it’s unclear just how Trump can reduce energy and household costs without sacrificing growth or corporate profits.

Outgoing Vice President Kamala Harris greeted the vice president-elect when he arrived.

Usually, only the president-elect comes to the White House on Inauguration Day before the swearing-in.

Harris and Vance have not yet had a formal one-on-one meeting after the outgoing vice president did not invite him to visit the official residence on the grounds of the U.S. Naval Observatory.

Harris and Vance were accompanied by their spouses and all shook hands and posed for a picture.

The lineup will include Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who served as Trump’s press secretary, along with former aide Kellyanne Conway and Texas Rep. Ronny Jackson, who was Trump’s White House physician.

Former White House adviser Peter Navarro, who served prison time related to the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol and is returning to Trump’s administration as a senior counselor for trade and manufacturing, is also expected to give remarks.

Kash Patel, Trump’s pick to lead the FBI, and Trump’s “border czar” Tom Homan will also attend.

The crowd inside the Capital One Arena cheered enthusiastically when the Jumbotrons began broadcasting President-elect Donald Trump and his wife, Melania, on their way to the White House.

Some chanted “USA! USA!” but it didn’t catch on with the half-full crowd, drowned out by the speakers playing The Killers song “Mr. Brightside.”

“One more selfie for the road. We love you, America,” the post on the social platform X read.

“I think this is democracy in action,” she told a reporter at the White House.

Trump has left St. John’s Episcopal Church after a prayer service ahead of the inauguration.

He and his wife, Melania, are next expected to be welcomed by President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden, where they will share tea and coffee at the White House.

The private meeting is another presidential transition tradition.

It’s a stark departure from four years ago, when Trump refused to acknowledge Biden’s victory or attend his inauguration.

Trump will sign an executive order declaring that the federal government would recognize only two genders: male and female, an incoming White House official said Monday.

The order undoes parts of one President Joe Biden signed on his first day in office four years ago. Trump’s order could restrict access to gender-affirming medical care and sports competitions for some transgender people.

The official said only two sexes will be recognized on passports and visas.

The move is not a surprise. Trump criticized transgender and nonbinary rights in his campaign, airing one ad more than 15,000 times that proclaimed, “Kamala is for them/them. President Trump is for you.”

Civil rights groups were preparing to challenge Trump’s restrictions in court before he took office.

“We are going to persevere, we’re going to continue in our work and we’re going to continue to protect trans rights throughout the country,” said Ash Orr, a spokesperson for Advocates for Trans Equality last week, anticipating such an order.

President Donald Trump is going to issue a series of orders aimed at remaking America’s immigration policies on his first day in office Monday — ending asylum access, sending troops to the southern border and ending birthright citizenship, an incoming White House official said.

It’s unclear how he would carry out some of his executive orders, including ending automatic citizenship for everyone born in the country, while others were expected to be immediately challenged in the courts.

The official spoke on condition of anonymity in order to preview some of the orders expected later Monday.

Immigrant communities were bracing for the crackdown that Trump had been promising throughout his campaign and up through a rally Sunday just ahead of his inauguration.

The Trumps held hands as they filed out of the church and the president-elect nodded and offered smiles to the churchgoers as he exited the sanctuary.

Hours before Trump and Vance are expected to be inaugurated, seats designated for Elon Musk, Tucker Carlson and others were among the closest to the platform where Trump will be taking the oath of office.

Even Musk’s mother, Maye Musk, had a better seat than the majority of House and Senate lawmakers.

“Good, it’s a beautiful day,” he said.

Biden and first lady Jill Biden greeted the vice president and her husband Doug Emhoff at the Pennsylvania Avenue side of the White House.

The prayer for Trump and Vice President-elect JD Vance asked that God give them “wisdom and strength to know and to do.”

Trump’s team released the video online on Monday ahead of his swearing-in and it portrays him as an outsider who overcame his legal problems to win a comeback to the White House, ushering in a new chapter for America.

The video stitches together footage of his courthouse appearances for his criminal trial last year, his mug shot from another criminal case in Georgia and images of prosecutors and judges involved in some of the other cases he faced, along with images of his visits to UFC matches, his campaign and the Republican National Convention.

In a voice-over, Trump tells his supporters they have to “never ever, ever give up” and “treat the word impossible as nothing more than motivation.”

The video was first reported by Fox News Digital.

“Having the cameras off is a gift. The rest of the day will be very public,“ he said.

Cupboards and drawers have been emptied, the walls are bare and all personal items have been boxed up, including in press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre’s office.

Most of the press office staff wrapped up their government service last week.

A couple of press secretaries and assistants remain to see Biden through tea with Trump, the ride to the Capitol for the inauguration and Biden’s departure ceremony afterward.

President-elect Donald Trump has entered St. John’s Episcopal Church with his wife, Melania, for a service ahead of the inauguration, taking part in a long presidential tradition.

The Trumps spent the night at Blair House and will head to the White House for a coffee and tea with President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden following the service.

Biden had ordered that flags at federal facilities be lowered for 30 days out of respect for Jimmy Carter. The former president died on Dec. 29 at the age of 100.

Many governors also lowered the flag on state buildings.

But Trump complained that flags at the U.S. Capitol would fly at half-staff when he takes the oath of office to begin his second term.

Many Republican governors since have said the flag will be raised for the inauguration and lowered again afterward to respect Carter.

The White House had said Biden would not consider reversing or reevaluating the flag order.

Elon Musk and several of President-elect Trump’s Cabinet picks are already in the pews awaiting his arrival and the start of the service at the historic church on Lafayette Square.

Among the other guests are Secretary of State-designate Marco Rubio, Argentina President Javier Milei and the president’s daughter Ivanka Trump

Long lines stretched around the icy sidewalks and security perimeters of Capitol One Arena where ticket holders hoped to be among the 20,000 to get in.

Inside the arena before 8:30 a.m. the atmosphere was calm — the seats largely empty as workers finalized preparations and the media set up cameras and lights on the arena floor.

Security and inauguration staff scolded members of the press inside for stray equipment in the hallways, saying doors would be held for the general public until it was cleared. Around 8:25 a.m., the public started to take their seats as the Katrina and the Waves song “Walking on Sunshine” blared on the speakers.

Pam Pollard, a former National Committeewoman from Oklahoma City, arrived in Washington nearly a week ago and said she was in line to sit in a reserved section at the inauguration before it was moved inside.

She agreed with the change because people could get so caught up in the moment that they might endanger themselves.

Pollard, 65, who was at the state convention and the Republican National Convention that formally nominated Trump to be the party’s candidate, suggested people break up into watch parties.

“We all believe God’s hand has been on this man to be elected,” she said. “We don’t have to stand out here on the lawn to show our support, our unity.”

“Trans-Atlantic relations are of the utmost importance for Germany and for Europe,” German Chancellor Olaf Scholz told the Rheinische Post. “And NATO is the guarantor of our security. That is why we need stable relations with the USA.”

Scholz’s comments came hours before Trump’s inauguration.

The German chancellor also said that “as the European Union, we can also build on our own strength. As a community of more than 400 million Europeans, we have economic weight.”

He said he had already talked to Trump on the phone twice without elaborating when the calls took place.

Retired Gen. Mark Milley says President Joe Biden issuing a pardon to shield him from potential revenge by the incoming Trump administration means he won’t have to spend time avoiding “retribution for perceived slights.”

“I do not wish to spend whatever remaining time the Lord grants me fighting those who unjustly might seek retribution for perceived slights,” Milley said in a statement.

Milley is the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He called Trump a fascist and detailed Trump’s conduct around the deadly Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Milley said he was “deeply grateful for the President’s action.”

Vince Filippone, 71, and his wife, Diane, 68, came to the inauguration from their central Florida home — a gift from their sons, who joined them.

Filippone quipped he hadn’t worn a heavy coat in years as they braved the frigid temperatures.

They rode the Washington Metro subway into the district’s downtown area and joined the thousands of people who began lining up before sunrise to get into the viewing arena where Trump’s victory celebration was held Sunday.

Far beyond being disappointed, the cancer survivor said he was “past excited. This is the trip of a lifetime.”

Biden pardoned members and staff of the Jan. 6 committee that investigated the attack, as well as the U.S. Capitol and D.C. Metropolitan police officers who testified before the committee about their experiences that day, overrun by an angry, violent mob of Trump supporters.

The committee spent 18 months investigating Trump and the violent insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021. It was led by U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., and Republican Liz Cheney, who later pledged to vote for Democrat Kamala Harris and campaigned with her. The committee’s final report found that Donald Trump criminally engaged in a “multi-part conspiracy” to overturn the lawful results of the 2020 presidential election and failed to act to stop his supporters from attacking the Capitol.

Trump may be breaking a tradition on Inauguration Day. No heads of state have previously made an official visit to the U.S. for the inauguration.

It’s not clear whether foreign leaders will attend the swearing-in ceremony or other events related such as inaugural balls.

Argentina’s President Javier Milei and Italy’s Premier Giorgia Meloni have spoken about being invited. The offices of Ecuadorean President Daniel Noboa and Paraguayan President Santiago Peña have also said they were invited and were planning to attend. The Salvadoran ambassador to the U.S. said there had been an invitation to the country’s President Nayib Bukele, but he is not likely to attend.

Last month, Trump transition spokesperson Karoline Leavitt said world leaders, including Chinese President Xi Jinping, had been invited. Jinping is unlikely to attend and it’s not clear whether he would send another official.

The “transfer of families” is a frenetic Inauguration Day ritual of approximately five hours where the White House is turned over from the outgoing presidential family to the incoming one.

In that time, while the outgoing and incoming presidents are together for the inaugural ceremony — White House residence staff hustle to inventory belongings, pack and move out one family and prepare the residence for its new occupants.

The process wasn’t always so efficient, though.

After the disputed election of 1876, outgoing President Ulysses S. Grant suggested that his successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, take the oath of office two days early to prevent potential unrest.

Hayes did that but then took a second oath as scheduled. Grant, though, didn’t actually vacate the White House until after Haye’s second swearing-in.

Biden has set the presidential record for most individual pardons and commutations issued; he announced on Friday he would commute the sentences of almost 2,500 people convicted of nonviolent drug offenses.

He previously announced he was commuting the sentences of 37 of the 40 people on federal death row, converting their punishments to life imprisonment just weeks before Trump, an outspoken proponent of expanding capital punishment, takes office. In his first term, Trump presided over an unprecedented spate of executions, 13, in a protracted timeline during the coronavirus pandemic.

President Joe Biden has pardoned Dr. Anthony Fauci, retired Gen. Mark Milley and members of the House committee that investigated the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, using the extraordinary powers of his office in his final hours to guard against potential “revenge” by the incoming Trump administration.

The decision by Biden comes after Donald Trump warned of an enemies list filled with those who have crossed him politically or sought to hold him accountable for his attempt to overturn his 2020 election loss and his role in the storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Trump has selected Cabinet nominees who backed his election lies and who have pledged to punish those involved in efforts to investigate him.

“The issuance of these pardons should not be mistaken as an acknowledgment that any individual engaged in any wrongdoing, nor should acceptance be misconstrued as an admission of guilt for any offense,” Biden said in a statement. “Our nation owes these public servants a debt of gratitude for their tireless commitment to our country.”

▶ Read more about Biden’s last-minute pardons

The White House’s official X account, and its 37 million followers, will shift around midday from Joe Biden to Donald Trump.

The process is similar to Inauguration Day 2017 when the @POTUS account — created during Barack Obama’s tenure — was transferred to Trump’s first administration.

The same will be true for @WhiteHouse, the first lady’s @FLOTUS and @VP for the vice president.

Twitter suspended Trump’s personal account, @realDonaldTrump, in 2021, after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

But Trump supporter Elon Musk later bought Twitter, renaming it X, and Trump rejoined the platform last summer — though he uses his Truth Social network more.

Congress directed in September 1788 that the presidential swearing-in ceremony occur on the first Wednesday in March. But George Washington wasn’t actually inaugurated until April 30, 1789, on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City, then the nation’s capital.

The capital was moved to Philadelphia in 1790 before construction was completed on the White House in 1800. There, Washington was sworn in for his second term in,1793, and John Adams was inaugurated in 1797.

Most inaugurations took place on March 4 until the ratification of the Twentieth Amendment in 1933, which set the ceremony for noon on Jan. 20.

Where inaugurations took place also traditionally varied. But they’ve been held on the Capitol’s western front, facing the National Mall, since Ronald Reagan took office in January 1981.

“The people who are coming out and participating directly are still a small subset of the entire universe of what we call celebrity,” said Robert Thompson, a professor of pop culture at Syracuse University. “But we’re seeing a lot more celebrities who are coming out and supporting Trump. There may not be that distinct division that we saw before.”

There may still be a tinge of stigma, however. Thompson pointed to the statement from The Village People, in which they offered a justification their involvement, which he likened to an apologia.

Also, Thompson said, “The idea of being featured in a big national civic ritual perhaps can transcend political identity.”

The participation of people like Underwood is not going to change anyone’s mind about Trump, Thompson said. It could, however, change minds about the artist. On social media, some declared they were going to delete Underwood’s songs from their playlists.

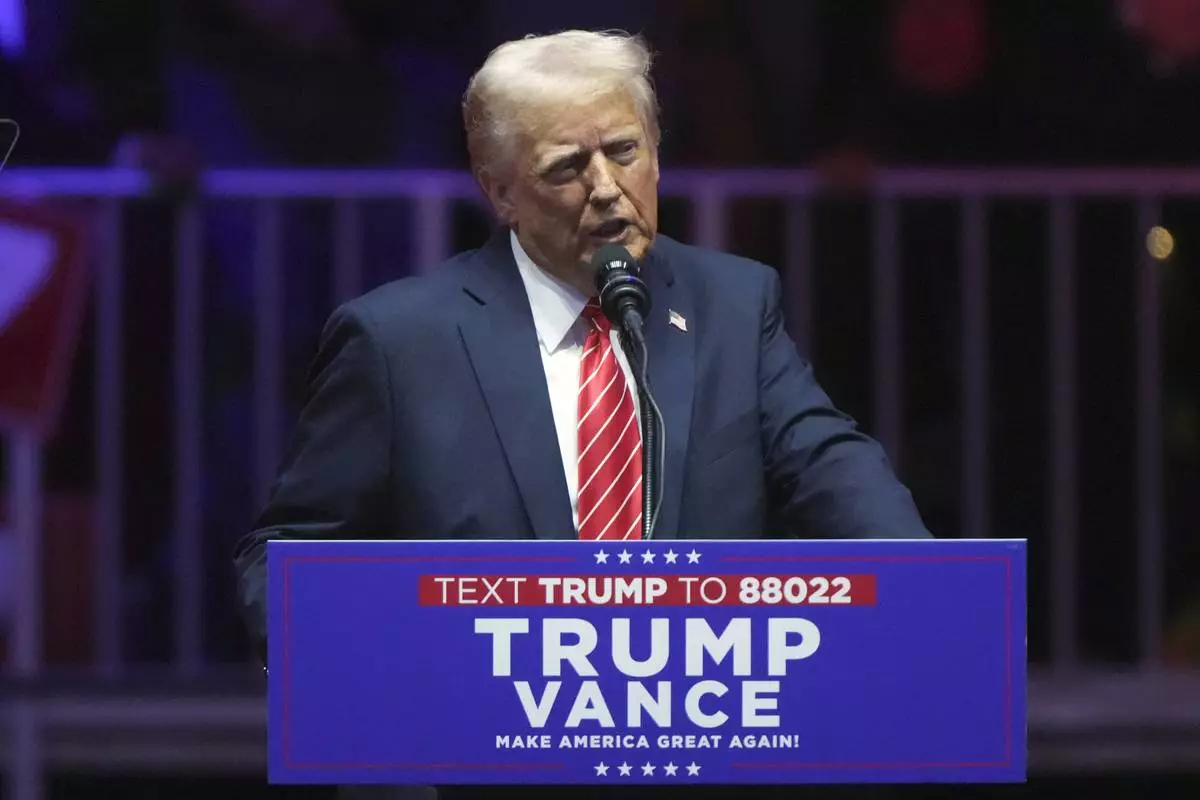

Addressing a packed crowd at Capital One Arena in Washington, D.C., Trump stayed consistent with the framing he often used in his campaign.

He criticized Biden’s term as a “failed administration” and promised to “end the reign of a failed and corrupt political establishment.”

“Tomorrow, at noon, the curtain closes on four long years of American decline and we begin a brand-new day of American strength and prosperity, dignity and pride,” he told supporters.

Carrie Underwood might not be Beyoncé or Garth Brooks in the celebrity superstar ecosystem. But the singer’s participation in President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration is nevertheless a sign of the changing tides, where mainstream entertainers, from Nelly to The Village People are more publicly, more enthusiastically associating with the new administration.

Eight years ago, Trump reportedly struggled to enlist stars to be part of the swearing-in and the various glitzy balls that follow. The concurrent protest marches around the nation had more famous entertainers than the swearing-in.

There were always some celebrity Trump supporters, like Kid Rock, Hulk Hogan, Jon Voight, Rosanne Barr, Mike Tyson, Sylvester Stallone and Dennis Rodman, to name a few. But Trump’s victory this time around was decisive and while Hollywood may always skew largely liberal, the slate of names participating in his inauguration weekend events has improved.

Kid Rock, Billy Ray Cyrus, The Village People, Lee Greenwood all performed at a MAGA style rally Sunday. Those performing at inaugural balls include the rapper Nelly, country music band Rascal Flatts, country singer Jason Aldean and singer-songwriter Gavin DeGraw.

Trump forecast signing as many as 100 executive orders on his first day, possibly covering deportations, the U.S.-Mexico border, domestic energy, Schedule F rules for federal workers, school gender policies and vaccine mandates, among other Day 1 promises made during his campaign. He’s also promised an executive order to give more time for the sale of TikTok.

Trump has asked Rep. Jeff Van Drew, R-N.J., to write an order stopping the development of offshore windmills for generating electricity.

Many of the Republican’s measures are likely to draw Democratic opposition.

And in several major cases, the orders will largely be statements of intent based off campaign promises made by Trump.

▶ Read more about Trump’s planned executive orders

The U.S. flag over the Capitol will be flying at full-staff for Donald Trump’s swearing-in.

That’s despite an order from President Joe Biden that flags be lowered for 30 days following the Dec. 29 death of former President Jimmy Carter.

President-elect Donald Trump talks with Vice President-elect JD Vance and Usha Vance as he arrives for a service at St. John's Church, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington, ahead of the 60th Presidential Inauguration. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

Staff prepare before the 60th Presidential Inauguration in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025. (Chip Somodevilla/Pool Photo via AP)

President-elect Donald Trump arrives for a service at St. John's Church, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington, ahead of the 60th Presidential Inauguration. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

President-elect Donald Trump shakes hands with Vice President-elect JD Vance as Usha Vance watches as he arrives for a service at St. John's Church, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington, ahead of the 60th Presidential Inauguration. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden greet Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Doug Emhoff upon their arrival at the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden greet Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Doug Emhoff upon their arrival at the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden walk out to greet Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Doug Emhoff upon their arrival at the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

President Joe Biden and first lady Jill Biden walk out to greet Vice President Kamala Harris and second gentleman Doug Emhoff upon their arrival at the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

President-elect Donald Trump talks with Vice President-elect JD Vance and Usha Vance before a service at St. John's Church, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington, ahead of the 60th Presidential Inauguration. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania are greeted as they arrive for church service at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania arrive for church service at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania arrive for church service at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. arrives for a church service to be attended by President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Ivanka Trump and her family arrive for a church service to be attended by President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

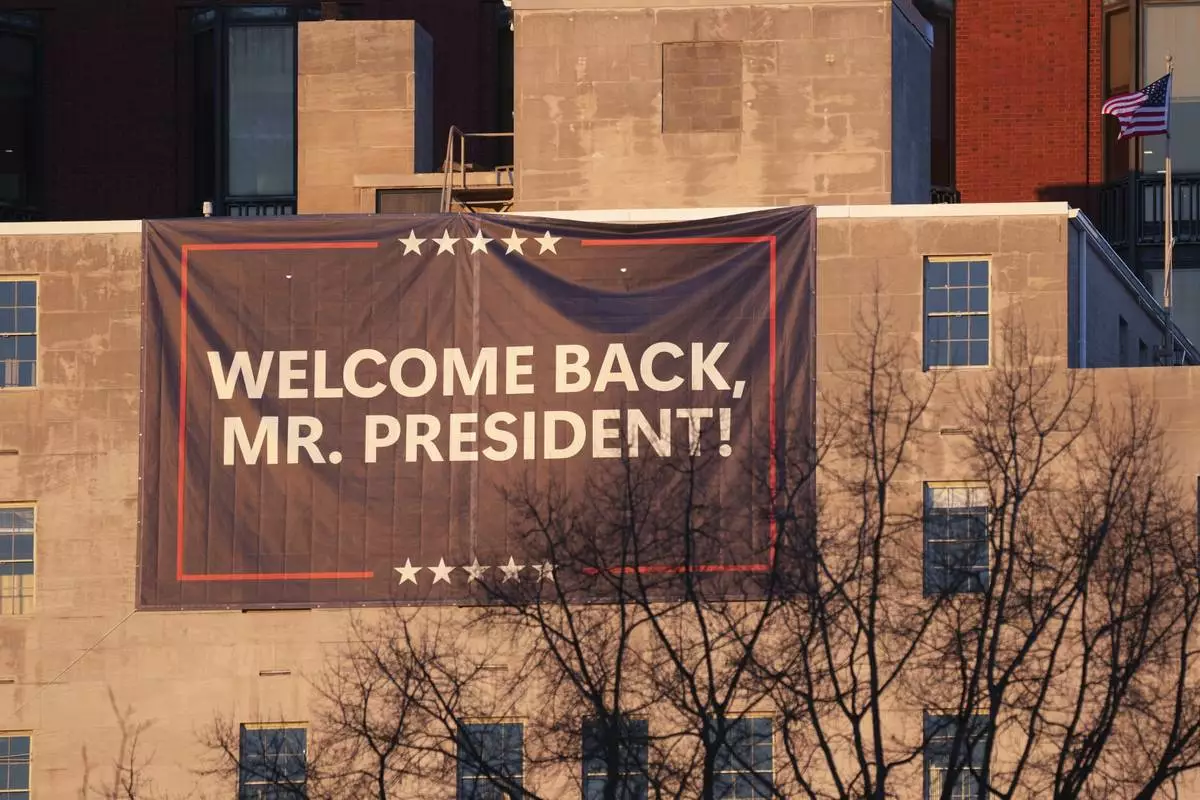

A sign is seen near St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, where President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania will attend an early morning service to start Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Rudy Giuliani, center arrives for a church service to be attended by President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

Eric Trump and wife Lara, daughter Carolina and son Luke, arrive for church service to be attended by President-elect Donald Trump and his wife Melania, at St. John's Episcopal Church across from the White House in Washington, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, on Donald Trump's inauguration day. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

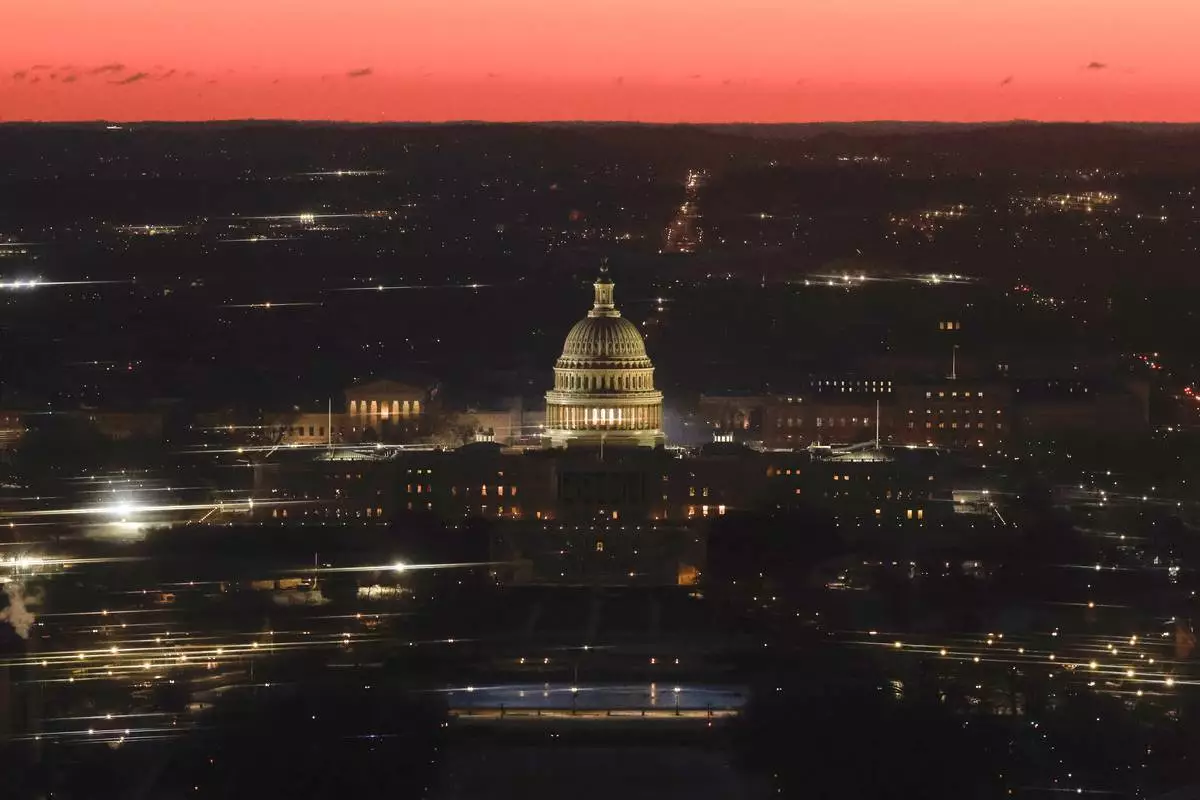

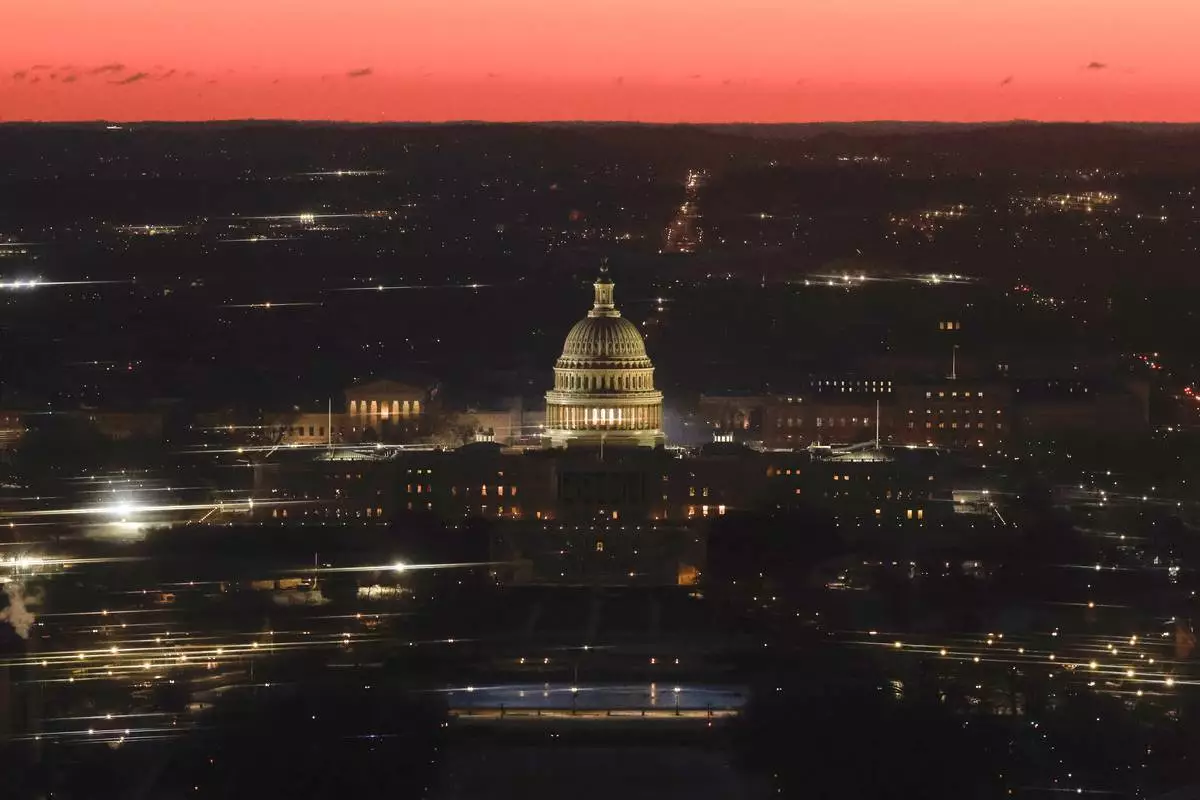

The U.S. Capitol is seen from the top of the Washington Monument at dawn on Inauguration Day, Monday, Jan.20, 2025 in Washington. (Brendan McDermid/Pool via AP)

The White House is seen ahead of the inauguration of President-elect Donald Trump, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

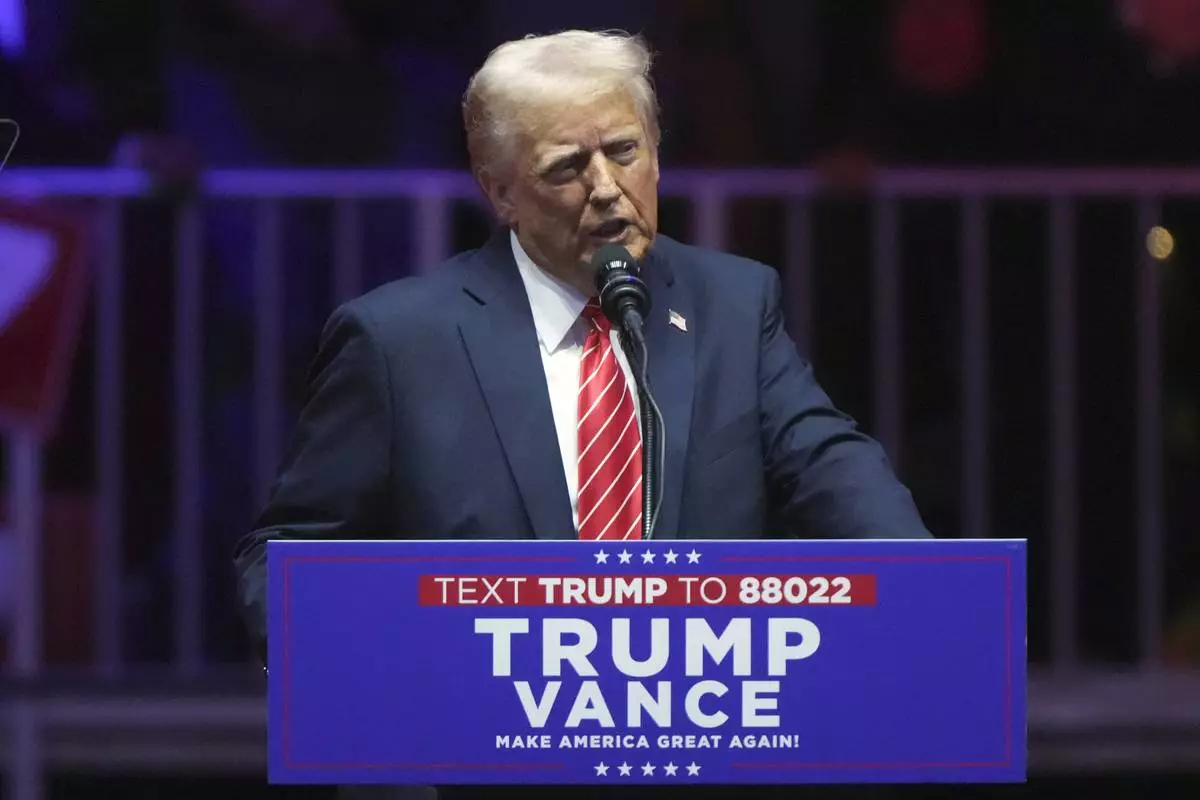

President-elect Donald Trump speaks at a rally ahead of the 60th Presidential Inauguration, Sunday, Jan. 19, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

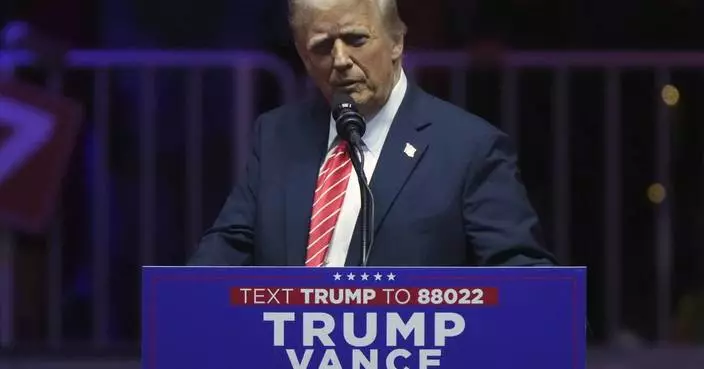

President-elect Donald Trump speaks at a rally ahead of the 60th Presidential Inauguration, Sunday, Jan. 19, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)