UNITED NATIONS (AP) — The U.N. General Assembly's yearly meeting of world leaders is here — and with it, an array of acronyms, abbreviations, titles and terms that can be confounding to observers. Here is some key vocabulary, decoded.

UNGA: Acronym (yes, people do pronounce it “UN'-gah”) for the U.N. General Assembly's “High-level Week.” It's the international organization's biggest annual event, inviting presidents, prime ministers, monarchs and other top leaders of all 193 U.N. member countries to speak to the world and each other. Although New Yorkers sometimes just use “General Assembly” to describe what many experience mainly as a week of street closures and whizzing motorcades, the assembly actually isn't just this meeting. It's a body that convenes countries' ambassadors throughout the year to discuss a wide range of global issues and vote on resolutions.

GENERAL DEBATE: The centerpiece of the week, it gives each country's leader (or a designee) the mic for a state-of-the-world speech from its viewpoint. There is a theme, chosen by the assembly's president — this year's is about “leaving no one behind” and “acting together” to advance peace, sustainable development and human dignity. But speakers use the opportunity to opine on the planet's biggest issues and hotspots, spotlight domestic accomplishments and needs, air grievances, and project statesmanship. Dignitaries are asked to wrap up within 15 minutes, but there's no buzzer or Oscars-style music. While the “debate” is less an interactive back-and-forth than a series of speeches, rebuttals are allowed at the end of each long day, and some embittered neighbor nations routinely go multiple rounds.

BILATERAL (or “bilat,” for short): Private meetings between leaders of one country and another. Some argue the real value of UNGA lies in these tête-à-têtes and other personal, off-camera encounters among decision-makers.

MINISTERIAL: Applies to meetings of cabinet-level officials, such as foreign ministers, from different countries.

SECURITY COUNCIL: The U.N.'s most powerful component, charged with maintaining international peace and security. The 15-member council can enact binding (though sometimes ignored) resolutions, impose sanctions and deploy peacekeeping troops. While this week is the Assembly's show, the council generally holds at least one meeting of its own with high-wattage attendees in town for the events next door. This week, there are set to be three council sessions, on Ukraine, the Mideast and the topic of “leadership for peace.” Who's on the council? Read on.

P5: The Security Council's five permanent members with veto power. Under a structure set up in 1945, they are China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

E10: The Security Council's 10 elected, non-permanent members. The General Assembly elects them for two-year terms in seats allocated by region. Calls for council reform are an UNGA staple. One major complaint is the lack of permanent members from Africa and the Latin America-Caribbean region, though some other nations also have angled for years for a permanent presence.

G77: Stands for the “Group of 77,” a developing-countries interest group that formed within the U.N. in 1964. Despite its name, it actually now has 134 members.

COP29: A major U.N. global climate conference coming up in November in Baku, Azerbaijan.

1.5 DEGREES: A crucial climate threshold. Under the 2015 Paris climate accord, countries agreed to work to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) over pre-industrial times. The earth already has warmed at least 1.1 degrees (2 degrees Fahrenheit) since the mid-1800s.

SDGs: The U.N.'s “ sustainable development goals, ” which range from combating climate change to eliminating hunger and poverty to achieving gender equality. The U.N.'s member countries adopted the goals in 2015 as a 15-year action plan, but the pace is seriously lagging. UNGA week this year began with a “Summit of the Future,” on Sunday and Monday, that's meant to “turbocharge the SDGs,” as U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres has put it. If that sounds a lot like the “SDG summit” during last year's high-level week, well... consider it a sign of both the emphasis on and elusiveness of these grand goals.

SIDS: At the U.N., this stands for some 39 “ small island developing states. ” UNGA is an important platform for them to elevate concerns such as climate change and the existential threat they face from projections of rising seas and intensifying storms — often a painfully timely subject at a meeting that falls in the thick of the Atlantic hurricane season.

BRICS: A developing-economies coalition that initially included Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates joined this year. Azerbaijan and Malaysia have formally applied, and Saudi Arabia has said it’s considering doing so. There are many international groups centered around regional, economic, defense or other ties, but BRICS has gotten attention lately as a growing venue for Chinese-Russian influence when those powers are increasingly at odds with the West.

LDCs: Very poor nations that are known at the U.N. as “ least-developed countries.” Forty-five nations currently meet the criteria, which include a gross national income of $1,088 or less per person per year.

NGO: “Non-governmental organization,” such as an advocacy group, charitable foundation, nonprofit relief organization or other entity under the umbrella of what the U.N. likes to call civil society organizations.

IFIs: International financial institutions, including the so-called Bretton Woods institutions — the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which were established at a 1944 U.N. conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Critics — including Guterres — see the Bretton Woods duo as sclerotic entities that have badly failed poor and developing countries. The institutions have defended their work while saying they are trying to evolve.

MULTILATERALISM: Global or near-global partnership that is united and collectively develops enduring rules and shared norms — the idea that undergirds the U.N. itself and which many warn is under threat.

MULTIPOLAR: A scenario in which there are several different and sometimes competing centers of power, not a single superpower or two.

MULTISTAKEHOLDER: An approach to big projects and problem-solving that incorporates not only governments but businesses, NGOs and possibly others. Guterres is a fan, seeing this concept as key to the future of world cooperation. But some progressive groups view it as a sell-out to big corporations and other powers that be.

TWO-STATE SOLUTION: A concept for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by establishing an independent Palestinian nation living in peace alongside Israel. The framework was set down in the 1993 Oslo Accords and embraced by the U.N., but progress toward implementing it stalled long before the nearly year-old war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza.

SOUTH-SOUTH COOPERATION: Collaboration among countries, organizations and people in what's known as the Global South — a term that refers to developing nations that are largely, though not exclusively, in the Southern Hemisphere. Its aims include amplifying their voice in their own development and in international affairs.

UNILATERAL COERCIVE MEASURES: A usually critical way of describing sanctions imposed by one country in hopes of spurring some action in another.

See more of AP’s coverage of the U.N. General Assembly at https://apnews.com/hub/united-nations

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken speaks during "Summit of the Future" on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, Monday, Sept. 23, 2024. (Bryan R. Smith/Pool Photo via AP)

PLAINS, Ga. (AP) — Barack Obama and his advisers had two living former presidents to consider as they planned the 2008 Democratic National Convention.

Bill Clinton, eight years removed from the Oval Office, remained an image of centrist success that warranted a primetime speaking slot. But Jimmy Carter 's landslide defeat to Ronald Reagan lingered, even 28 years later.

“It was still an epithet: ‘Another Jimmy Carter,’” David Axelrod, top Obama adviser and confidant, said in an interview.

Obama decided against inviting Carter to the podium in Denver. The Georgia Democrat was featured in a video instead. “He, justifiably I think, he was a little miffed about that,” Axelrod said, adding that the decision was a “painful one” for Obama.

Now, as Carter nears his 100th birthday, the 39th president is being lauded not just for his longevity but for his accomplishments in government, his work as a global humanitarian and, as Obama himself said in a birthday tribute for his fellow Democrat, “for always finding new ways to remind us that we are all created in God's image.”

It's a preview, of sorts, of what will happen when Carter's long life ends and the nation pays tribute with state funeral rites in Washington. The praise, though, carries some irony for a president who campaigned against the ways of Washington and was an outcast of sorts even during his four years in the White House. To be sure, many presidential hopefuls campaign that way — Clinton and Reagan did it, too. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and Nikki Haley of South Carolina tried it as recently as the 2024 GOP primaries. But for Carter, being a loner even as a power player has been, perhaps, the defining posture of his life — sometimes by circumstance, sometimes by design.

“Jimmy Carter was always an outsider,” said biographer Jonathan Alter.

That identity traced back to Carter’s earliest years, growing up on a farm outside of his tiny hometown in south Georgia.

“He was from one of the wealthier families,” Alter noted, because James Earl Carter Sr. owned land that Black tenant farmers worked. But “when he went to school in Plains, and he had been barefoot for most of the year, the kids in town would think of him as a country bumpkin.”

Carter used the dichotomy to position himself for the presidency.

The commonly told version reads like cliché political fantasy: Earnest Baptist, peanut farmer and little-known governor from the Old Confederacy wins on a promise never to mislead Americans after the quagmire in Vietnam and Richard Nixon’s Watergate disgrace.

Yet when Carter decided to run, Nixon was the lone president he had ever met, and that was only briefly at a White House reception. Carter leaned on his extended family, close advisers and other Georgians to blanket key primary states throughout 1975 and early 1976. The inner circle was dubbed the “Georgia mafia.” The rest constituted the “Peanut Brigade.” By the time big-name candidates — senators, mostly — realized Carter was a contender, they could not stop him.

“His was a unique presidency in that it came from completely outside the party establishment and then continued to operate that way even in Washington,” said Joe Trippi, who worked for Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy, scion of a Democratic dynasty and Carter’s perpetual liberal rival.

“There was something so outside of Washington about them, such a loyalty and pride about those people,” Trippi said, noting that Carter mostly avoided appointing veterans of the Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Obama, Reagan and certainly Donald Trump challenged the establishment as candidates, but ultimately absorbed their parties. Carter, as the sitting president in 1980, had to watch convention delegates give Ted Kennedy roaring ovations even after Carter had won their bruising primary fight.

“The Democratic Party never belonged to Jimmy Carter,” Trippi said.

Nor did Carter master Capitol Hill, the national press corps or Washington’s social scene.

David Gergen, White House adviser to four presidents, said Carter “had some legislative successes” but missed on some of his most ambitious proposals because he wouldn’t always take command of negotiations with Congress.

“He handed that responsibility off” to Cabinet officers and aides, Gergen said. “That was not his forte.”

Carter in turns embraced and was frustrated by the dynamics.

When he pushed treaties ceding control of the Panama Canal but didn’t have enough support from Democrats, Carter looked to Gerald Ford, the man he defeated in 1976. The former president cajoled Republican senators and the treaties were adopted.

“I appreciate his help,” Carter wrote in his diary on March 16, 1978. “He’s done everything he promised.”

With the media, however, Carter had no escape hatch.

In late 1975 and 1976, as Carter grew into a plausible underdog, “the media loved him,” Alter said. But as a Southerner, he also faced deeply held biases, media historian Amber Roessner said.

“Any leading candidate was going to get extra scrutiny after Watergate,” she said, “but for Carter it was even more intense.”

When Carter described himself as a “born-again Christian,” the reference was commonly understood anywhere Baptist evangelicals are prevalent, but not so much in the Northeast, where national media is headquartered and where most voters in 1976 were mainline Protestant, Catholic, Jewish or nonreligious.

“Some members of the press," Carter complained in a Playboy magazine interview, "treat the South as a suspect nation.”

Long after leaving office, the U.S. Naval Academy graduate and engineer still bemoaned a political cartoon published around his inauguration that depicted his family approaching the White House with his mother, “Miss Lillian,” chewing on a hayseed.

In December 1977, when Carter's team had been in the West Wing less than a year, Washington Post society columnist Sally Quinn labeled them “an alien tribe,” incapable of “playing ‘the game.’” An elite Georgetown hostess herself, Quinn nodded to Washington’s “frivolity” even as she assessed ”the Carter people” as “not, in fact, comfortable in limousines, yachts, or in elegant salons, in black tie” or with “place cards, servants, six courses, different forks, three wines ... and after-dinner mingling.”

The uneasiness in Washington tracked Carter’s rise in Georgia.

After Earl Carter died, Jimmy Carter followed his father’s path as community leader and businessman. The younger Carter didn’t openly fight Jim Crow segregation laws but publicly refused to join the White Citizens Council. Then he took a state Senate seat in 1962 by challenging a local political boss who had rigged the election against him.

As a good-government lawmaker, Carter cast an outlier vote against money for a new governor’s mansion where his family eventually resided.

He first ran for governor in 1966, dissatisfied with the General Assembly. When he narrowly missed the Democratic runoff, Carter opted not to endorse a fellow racial moderate who had advanced, despite their shared distaste for the other contender: Lester Maddox, an avowed white supremacist. Maddox won. That silence enabled him to peel off Maddox supporters to become governor four years later in a race that built his grudge against media megaphones.

“The Atlanta Constitution,” he told Playboy in 1976, “categorized me during the gubernatorial campaign as an ignorant, racist, backward, ultraconservative, redneck south-Georgia peanut farmer,” while framing his big-city opponent as “an enlightened, progressive, well-educated, urbane, forceful, competent public official.”

Once in Atlanta, Carter previewed his Washington tenure, bucking legislators with a reorganization of state government that he pitched as necessary efficiency.

“He spent a lot of political capital making people mad, going after their fiefdoms,” said Terry Coleman, a Carter ally in the Assembly.

Georgia law dictated that Carter couldn’t succeed himself as governor. In Washington, it wasn’t his choice to serve just one term.

Carter returned home in 1981 “humiliated by the voters” and “at least somewhat depressed,” Alter said, but found his most sustained success as an outside influencer once he and Rosalynn Carter founded The Carter Center in Atlanta in 1982.

Decades of global democracy and human rights advocacy followed. Some of the former president’s international maneuvering annoyed his successors and Washington’s foreign policy establishment. Carter criticized U.S. wars in the Middle East, the West’s isolation of North Korea and Israel’s treatment of Palestine. He won a Nobel Peace Prize along the way.

“The best way to understand Carter as outsider is to see him as always understanding the rules of the insider circle,” Roessner said. “He just didn’t always play by them.”

FILE - Former President Jimmy Carter and President Clinton applaud former first lady Rosalynn Carter as she speaks, after Clinton awarded the couple the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, during a ceremony at the Carter Center in Atlanta, Aug. 9, 1999. (AP Photo/John Bazemore, File)

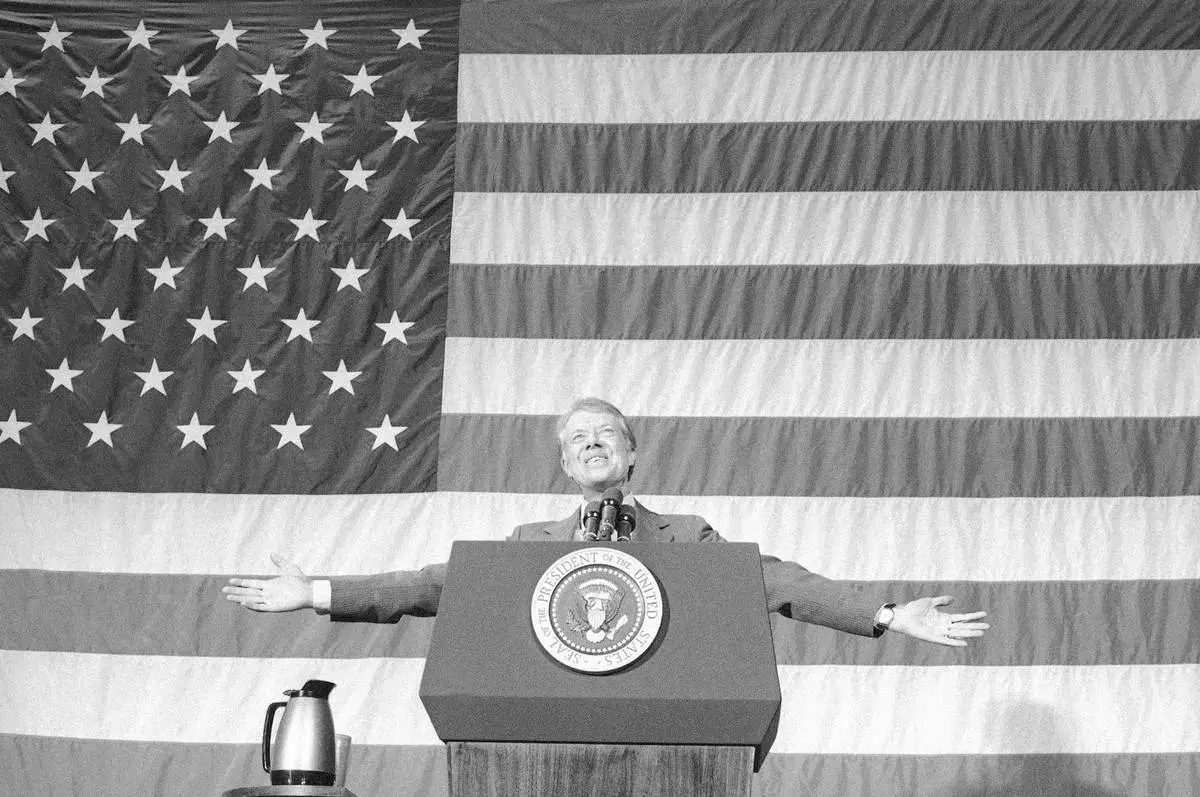

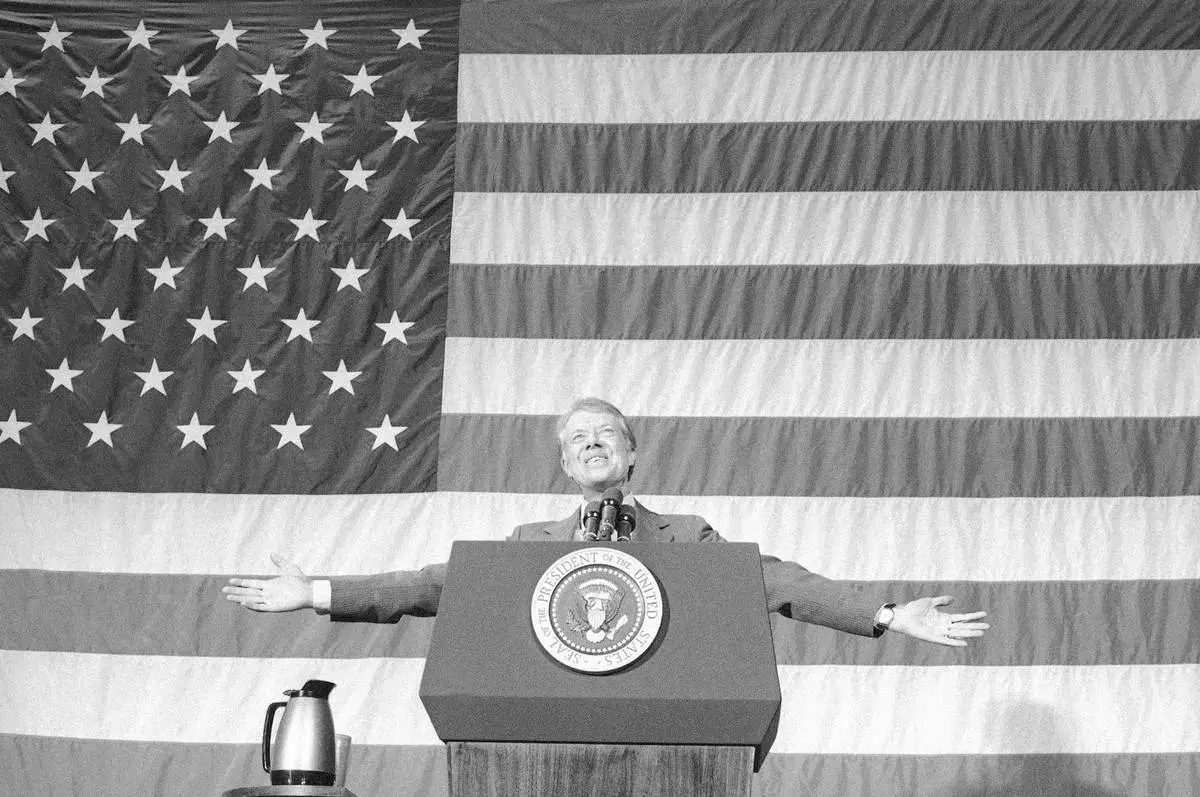

FILE - President Jimmy Carter acknowledges the applause of about 1,100 people gathered in the Elk City High School gym for a town meeting in Elk City, Okla., March 24, 1979. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - An estimated crowd of 35,000 people gather for a noontime speech by Presidential candidate Jimmy Carter in downtown Philadelphia, Oct. 29, 1976. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Sen. Joe Biden and former President Jimmy Carter are seen at the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Aug. 26, 2008. (AP Photo/Paul Sancya, File)

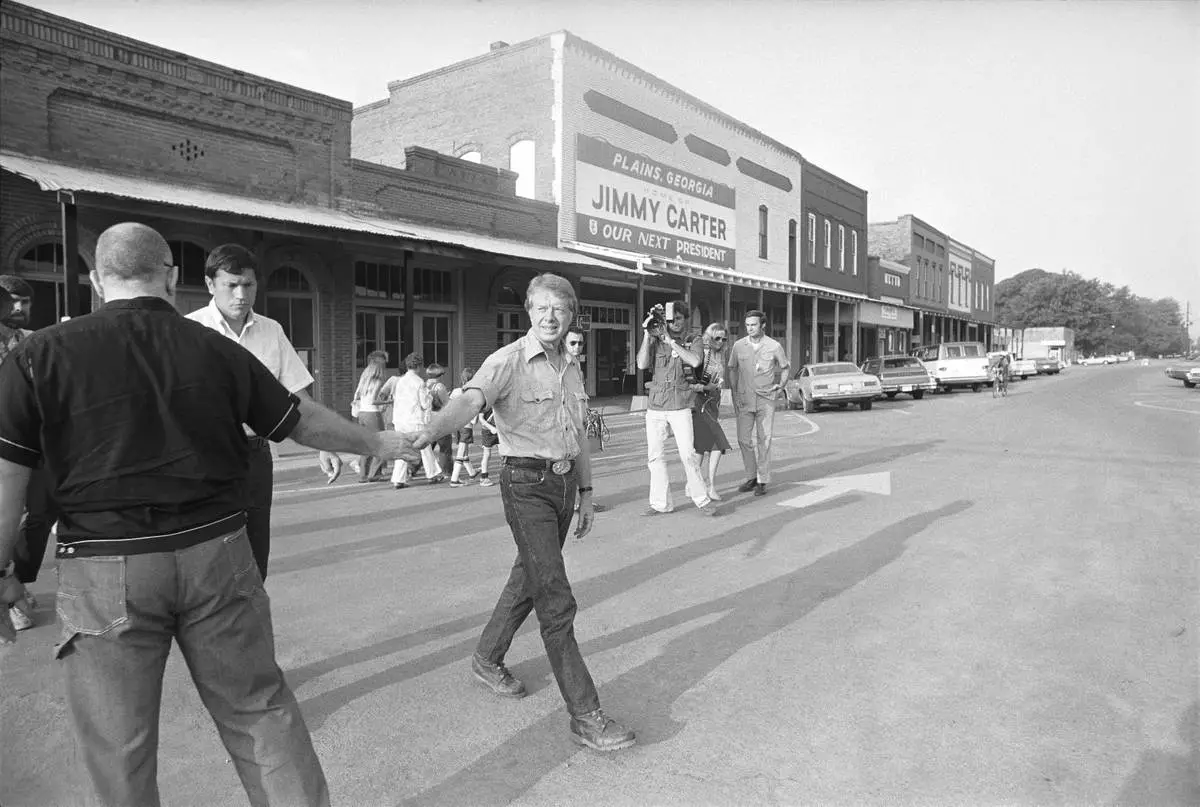

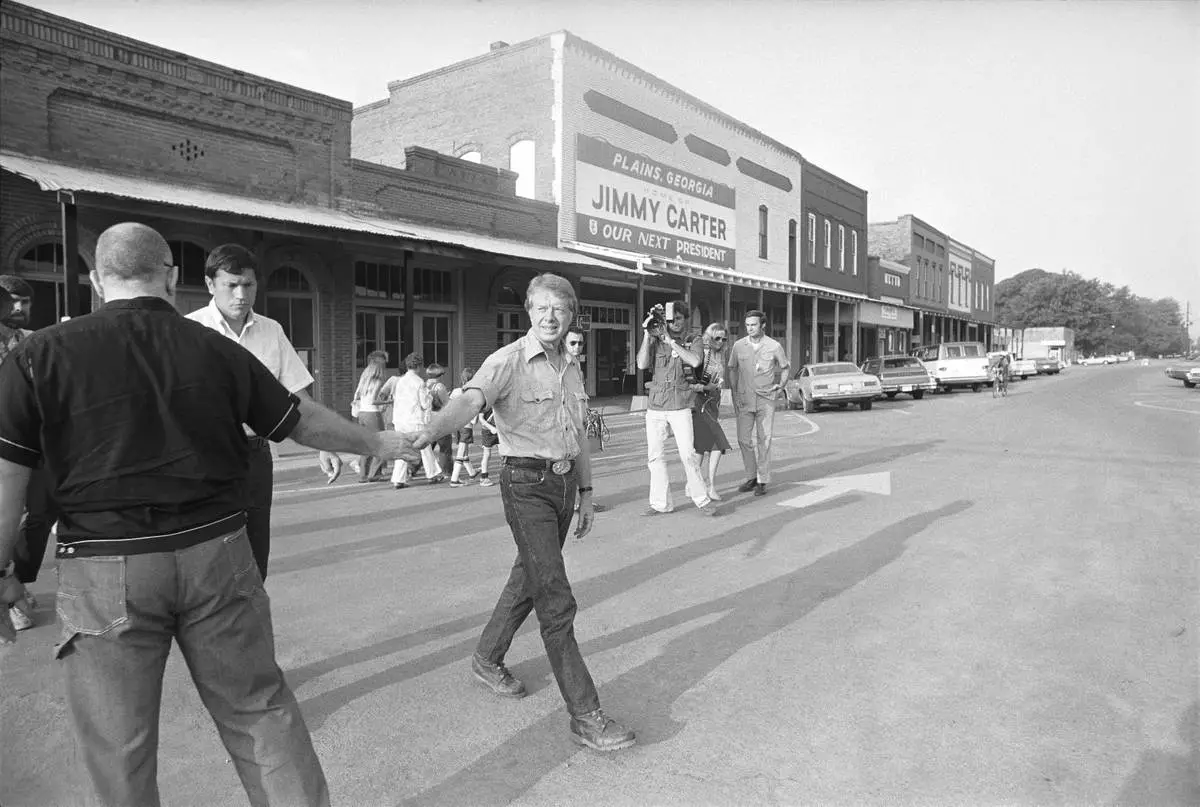

FILE - Democratic presidential nominee Jimmy Carter shakes hands with tourists as he takes an early morning walk down the main street of Plains, Ga., July 30, 1976. (AP Photo/Peter Bregg, File)

FILE - President Jimmy Carter carries a peanut plant as he follows his wife Rosalynn from the field at their Webster County, Ga., farm on August 19, 1978. (AP Photo/Jim Wells, File)