CHARLESTON, W.Va. (AP) — For decades, Jeff Card's family company was known for manufacturing the once ubiquitous tin boxes where people could buy newspapers on the street.

Today, reach into one of his containers and you may find something entirely different and free of charge: Naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug.

Click to Gallery

CHARLESTON, W.Va. (AP) — For decades, Jeff Card's family company was known for manufacturing the once ubiquitous tin boxes where people could buy newspapers on the street.

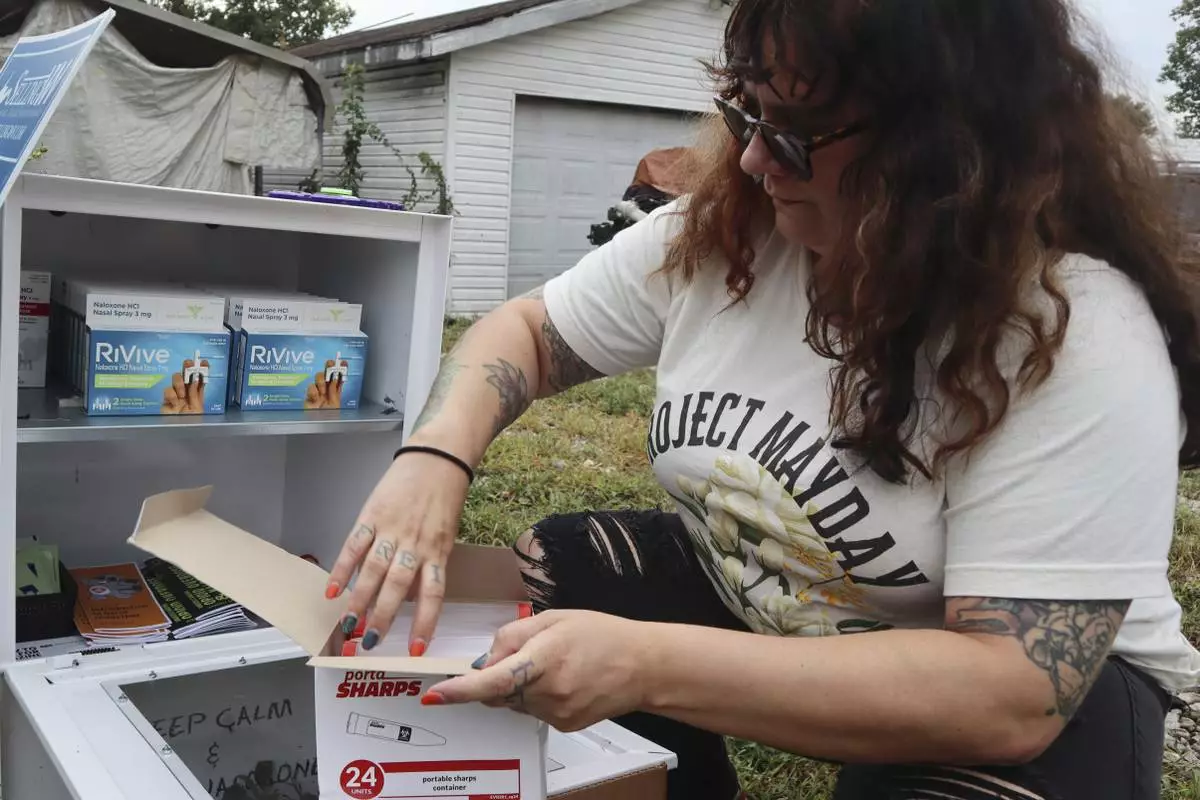

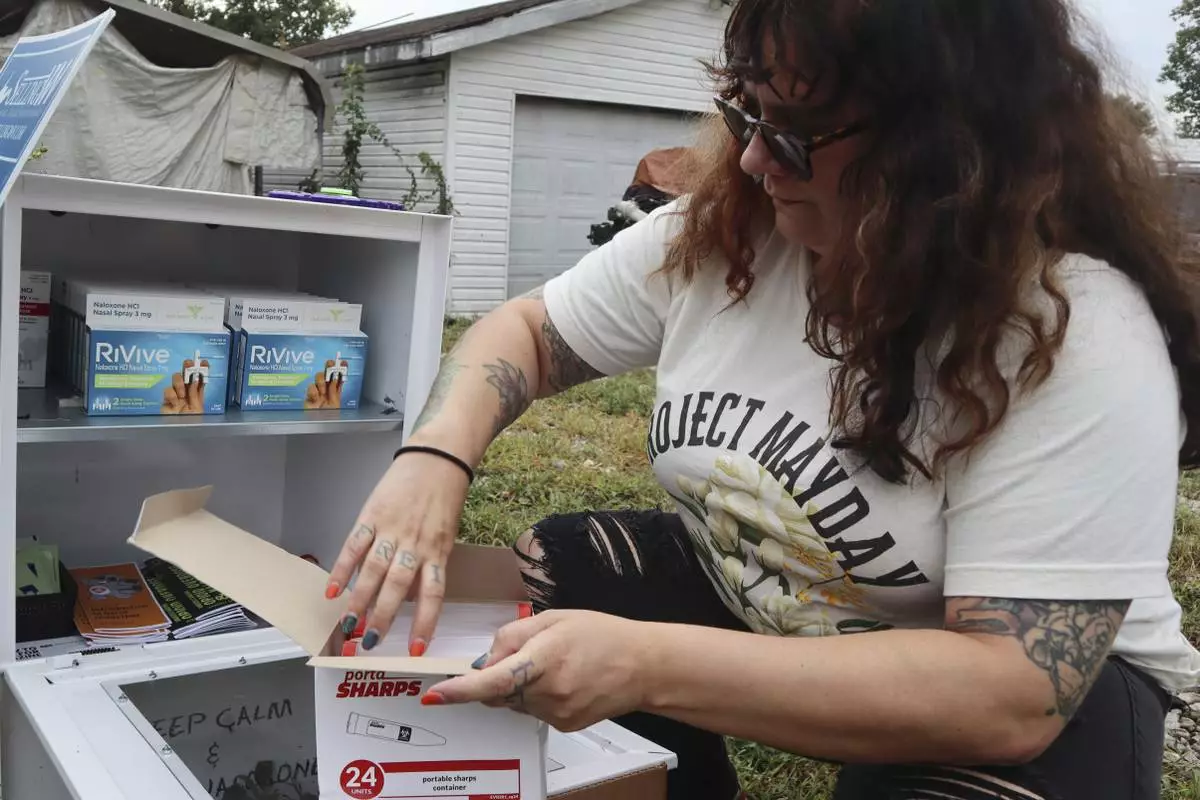

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residential neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

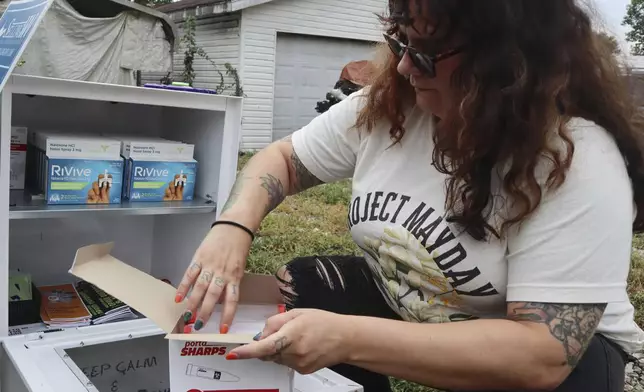

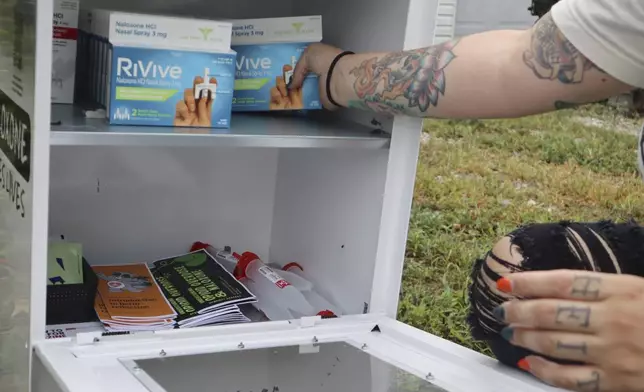

A new naloxone distribution box sits in a residential neighborhood in Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Naloxone distribution containers have been proliferating across the country in the more than a year since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved its sale without a prescription. Naloxone, a nasal spray most commonly known as Narcan, is used as an emergency treatment to reverse drug overdoses.

Such boxes — appearing in neighborhoods, in front of hospitals, health departments and convenience stores — are one way those supporting people with substance use disorder have sought to make Narcan, which can cost around $50 over the counter, accessible to those who need it most. Not unlike little free libraries that distribute books to anyone who wants one, the metal boxes used formerly as newspaper receptacles aren’t locked and don’t require payment. People can take as much as they think they need.

Advocates say the containers help normalize the medication — and are evidence of steadily reducing stigma around its use.

Sixty Narcan receptacles were distributed across 35 states in honor of Thursday's “Save a Life Day” — a naloxone distribution and education event started by a West Virginia nonprofit in 2020. Containers were purchased from Card's Texas-based Mechanism Exchange & Repair, which still serves newspaper customers but has expanded to manufacturing other products amid the newspaper industry's decline.

“It’s fortunate and unfortunate,” said Card, who started making the Narcan containers over two years ago. "Fortunate for us that we’ve got something to build, but unfortunate that this is what we have to build, given how bad the drug problem is in America.”

Opioid deaths were already at record levels before the coronavirus pandemic, but they skyrocketed when it hit in early 2020. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated there were about 85,000 opioid-related deaths in the 12 months that ended in April 2023. But since then, they fell. The CDC estimate for the 12 months that ended in April 2024 was 75,000 -- still higher than any point before the pandemic.

The reasons for the decline are not fully understood. But it does coincide with Narcan, a medication that’s been hard to get in some communities, becoming available over the counter, as well as with the ramping up of spending of funds from legal settlements between governments and drugmakers, wholesalers and pharmacies.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved use of Narcan to treat overdoses back in 1971, but its use was confined to paramedics and hospitals for decades. Narcan nasal spray was first approved by the FDA in 2015 as a prescription drug, and in March, it was approved for over-the-counter sales and started being available last September at major pharmacies.

“That took the barriers away. And that’s when we realized, ‘OK, now we need to increase access. How can we get naloxone into the communities?’” said Caroline Wilson, a West Virginia social worker and person in recovery who coordinated this year's Save a Life Day.

Last year, all 13 states in Appalachia participated in the day spearheaded by West Virginia nonprofit Solutions Oriented Addiction Response. Community organizations in hundreds of counties table in parking lots, outside churches and clinics handing out Narcan and fentanyl test strips and training people on how to use it. They also work to educate the public on myths surrounding the medication, including that it's unsafe to have in easily accessible places. Narcan has no effect on people who use it without opioids in their system.

This year, with the effort expanding to 35 states and a theme of “naloxone everywhere”, the group sent out 2,000 emergency kits containing one Narcan dose to be placed in locations like convenience store bathrooms or parks. The 60 tin newspaper boxes — which sell for around $350 apiece — were purchased with grants.

Aonya Kendrick Barnett's harm reduction coalition Safe Streets Wichita installed one of the Kansas' first Narcan receptacles — which she refers to as “nalox-boxes” — in February. The boxes, now sold by a few different companies, can look different, too. Some look like newspaper boxes, while others look like vending machines.

Since installing a vending machine Narcan container — which just requires a zip code be entered on the keypad to access the medication — it's distributed around 2,600 packages a month.

“To say, ‘Hey, we have a 24-hour vending machine, come over here and come get what you need — no judgment,’ is so bold in this Bible belt state and it’s helping me break down the the stigma," she said.

Kendrick Barnett said there's no place for judgment when it comes to what she calls live-saving health care: “People are going to use drugs. It’s not our job to condemn or condone it. It’s our job to make sure that they have the necessary health care that they need to survive.”

The Save a Life Day box her organization received is going to go in front of their new clinic, scheduled to open in October.

In Eerie, Pennsylvania, 74-year-old stained glass artist Larry Tuite said he grew concerned seeing overdoses increasing in his city. He began leaving Narcan packages on the windowsills of 24-hour markets in town that sell products like pipes and rolling papers. He was shocked at how quickly they disappeared.

“As many as I give out, I run through them really quickly," said Tuite, who keeps cases of the drugs stacked along the walls of his studio apartment.

The Save a Life Day container, which he got permission to put outside one such store, has helped him to disperse even more Narcan. At least a dozen people have been saved by the medication he's distributed, he said.

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery who runs a harm reduction coalition based out of Putnam County, West Virginia, said Narcan wasn't something she ever had access to when she was using opioids.

“People can just reach in and grab what they need — we didn't have that back then,” she said, while stocking a container in a residential neighborhood earlier this week. “To actually see that there is some access now — I’m glad that we’ve at least moved forward a little bit in that direction."

AP journalist Geoff Mulvihill contributed to this report.

A new naloxone distribution box sits in a residential neighborhood in Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residential neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

A new naloxone distribution box sits in a residential neighborhood in Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

OceanGate co-founder Stockton Rush said the carbon fiber hull used in an experimental submersible that imploded en route to the wreckage of the Titanic was developed with help of NASA and aerospace manufacturers, but a NASA official testified Thursday that the space agency actually had little involvement at all.

OceanGate and NASA partnered in 2020 with NASA planning to play a role in building and testing the carbon fiber hull. But the COVID-19 pandemic prevented NASA from fulfilling its role, other than providing some consulting on an early mockup, not the ultimate carbon fiber hull that was used for people, said Justin Jackson, a materials engineer for NASA.

“We provided remote consultations throughout the build of their one third scale article, but we we did not do any manufacturing or testing of their cylinders,” Jackson said.

At one point, Jackson said NASA declined to allow its name to be invoked in a news release by OceanGate. “The language they were using was getting too close to us endorsing, so our folks had some heartburn with the endorsement level of it,” he told a Coast Guard panel that’s investigating the tragedy.

Rush was among the five people who died when the submersible imploded in June 2023. The design of the company's Titan submersible has been the source of scrutiny since the disaster.

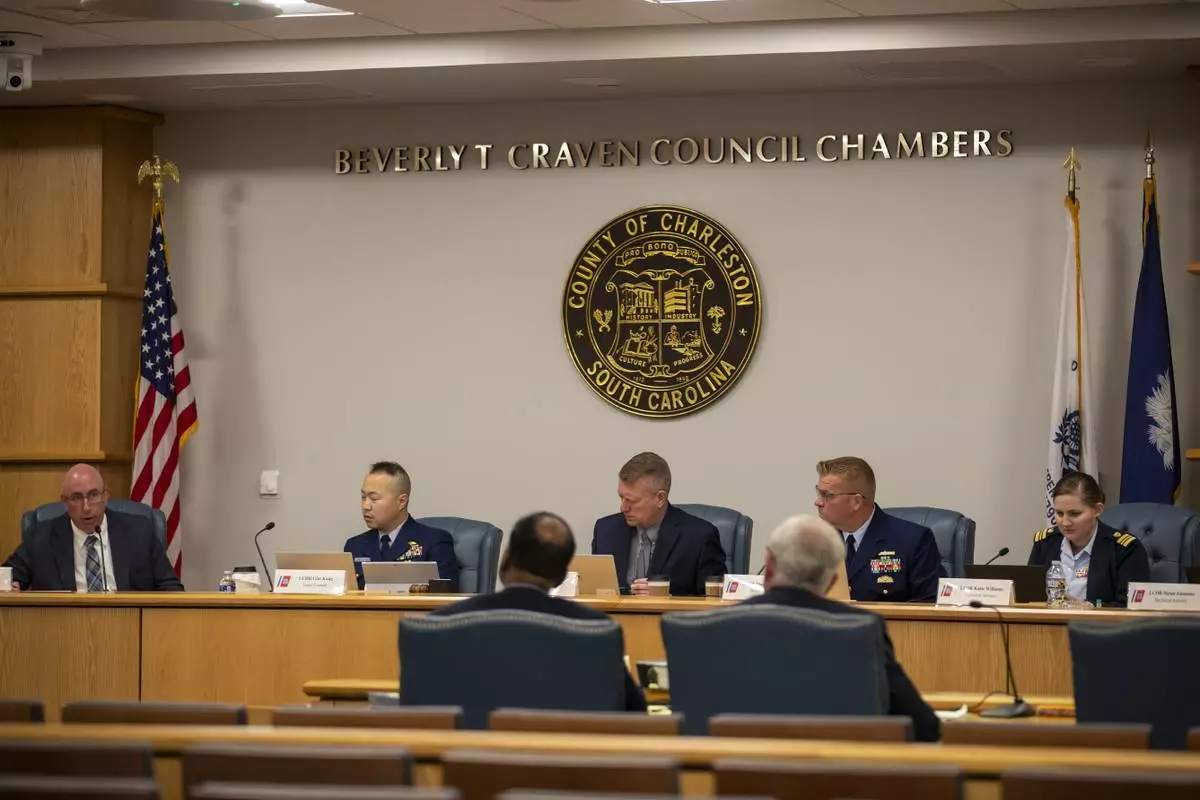

The Coast Guard opened a public hearing earlier this month that is part of a high level investigation into the cause of the implosion. Some of the testimony has focused on the troubled nature of the company.

In addition to Jackson, Thursday's testimony was to include Mark Negley of Boeing Co.; John Winters of Coast Guard Sector Puget Sound; and Lt. Cmdr. Jonathan Duffett of the Coast Guard Office of Commercial Vessel Compliance.

Earlier in the hearing, former OceanGate operations director David Lochridge said he frequently clashed with Rush and felt the company was committed only to making money. “The whole idea behind the company was to make money,” Lochridge testified. “There was very little in the way of science.”

Lochridge and other previous witnesses painted a picture of a company that was impatient to get its unconventionally designed craft into the water. The accident set off a worldwide debate about the future of private undersea exploration.

The hearing is expected to run through Friday and include more witnesses.

The co-founder of the company told the Coast Guard panel Monday that he hoped a silver lining of the disaster is that it will inspire a renewed interest in exploration, including the deepest waters of the world’s oceans. Businessman Guillermo Sohnlein, who helped found OceanGate with Rush, ultimately left the company before the Titan disaster.

“This can’t be the end of deep ocean exploration. This can’t be the end of deep-diving submersibles and I don’t believe that it will be,” Sohnlein said.

Coast Guard officials noted at the start of the hearing that the submersible had not been independently reviewed, as is standard practice. That and Titan’s unusual design subjected it to scrutiny in the undersea exploration community.

OceanGate, based in Washington state, suspended its operations after the implosion. The company has no full-time employees currently, but has been represented by an attorney during the hearing.

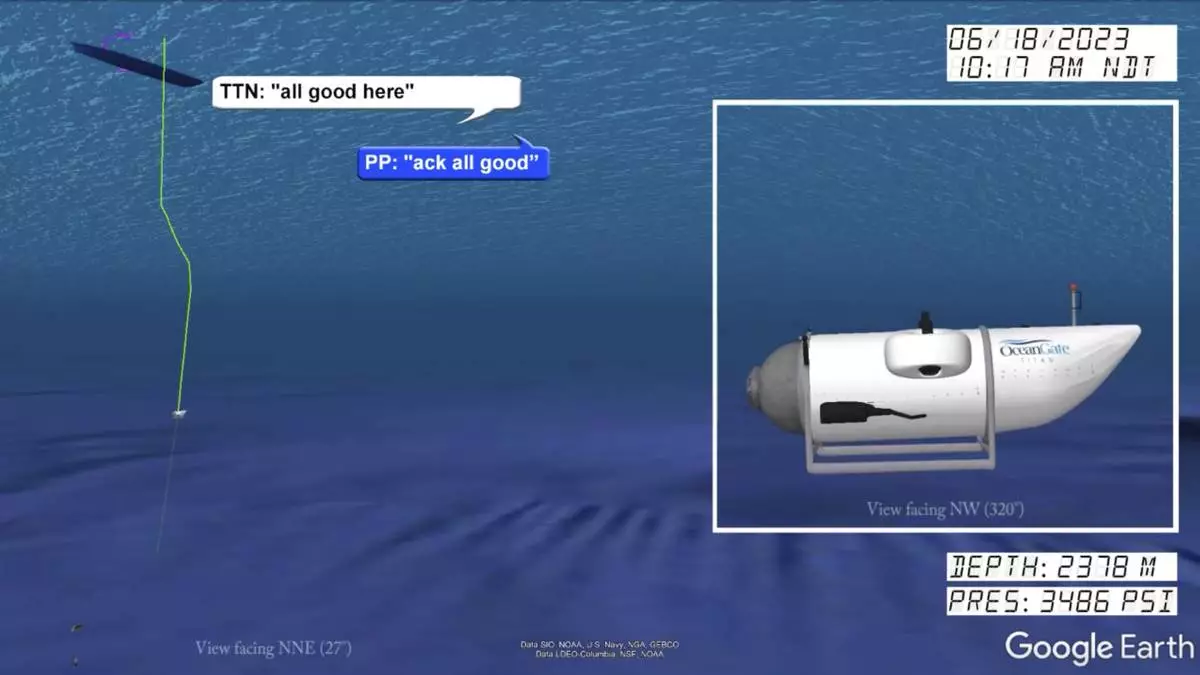

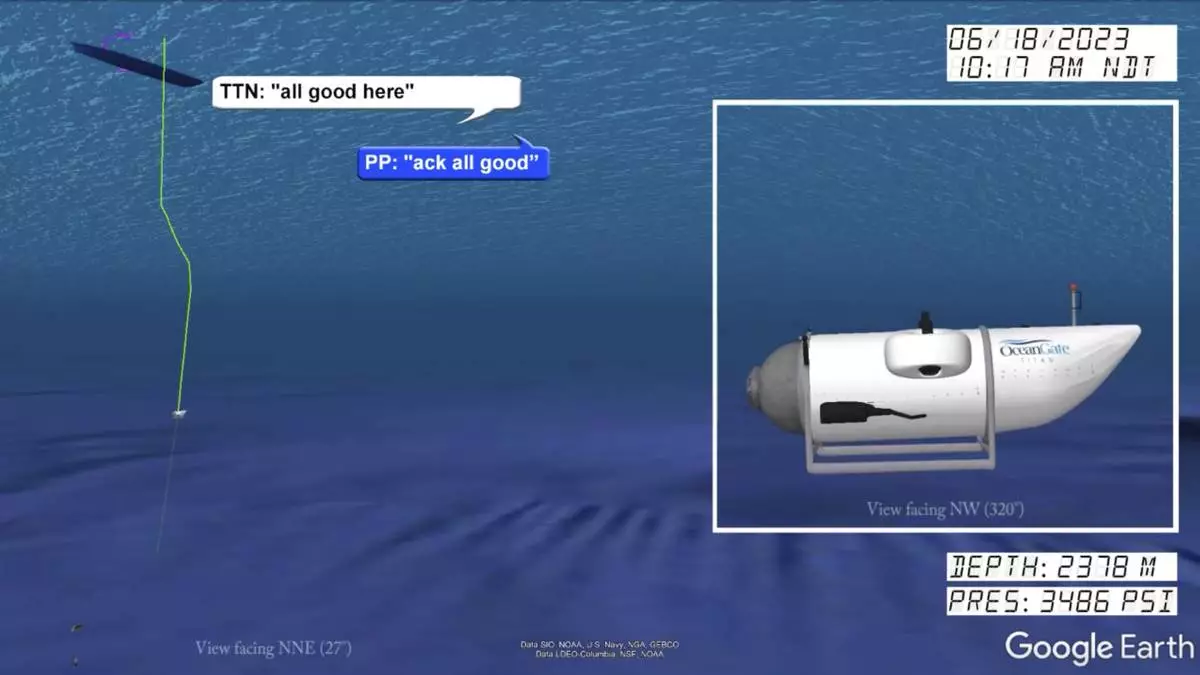

During the submersible’s final dive on June 18, 2023, the crew lost contact after an exchange of texts about Titan’s depth and weight as it descended. The support ship Polar Prince then sent repeated messages asking if Titan could still see the ship on its onboard display.

One of the last messages from Titan’s crew to Polar Prince before the submersible imploded stated, “all good here,” according to a visual re-creation presented earlier in the hearing.

When the submersible was reported overdue, rescuers rushed ships, planes and other equipment to an area about 435 miles (700 kilometers) south of St. John’s, Newfoundland. Wreckage of the Titan was subsequently found on the ocean floor about 330 yards (300 meters) off the bow of the Titanic, Coast Guard officials said. No one on board survived.

OceanGate said it has been fully cooperating with the Coast Guard and NTSB investigations since they began. Titan had been making voyages to the Titanic wreckage site going back to 2021.

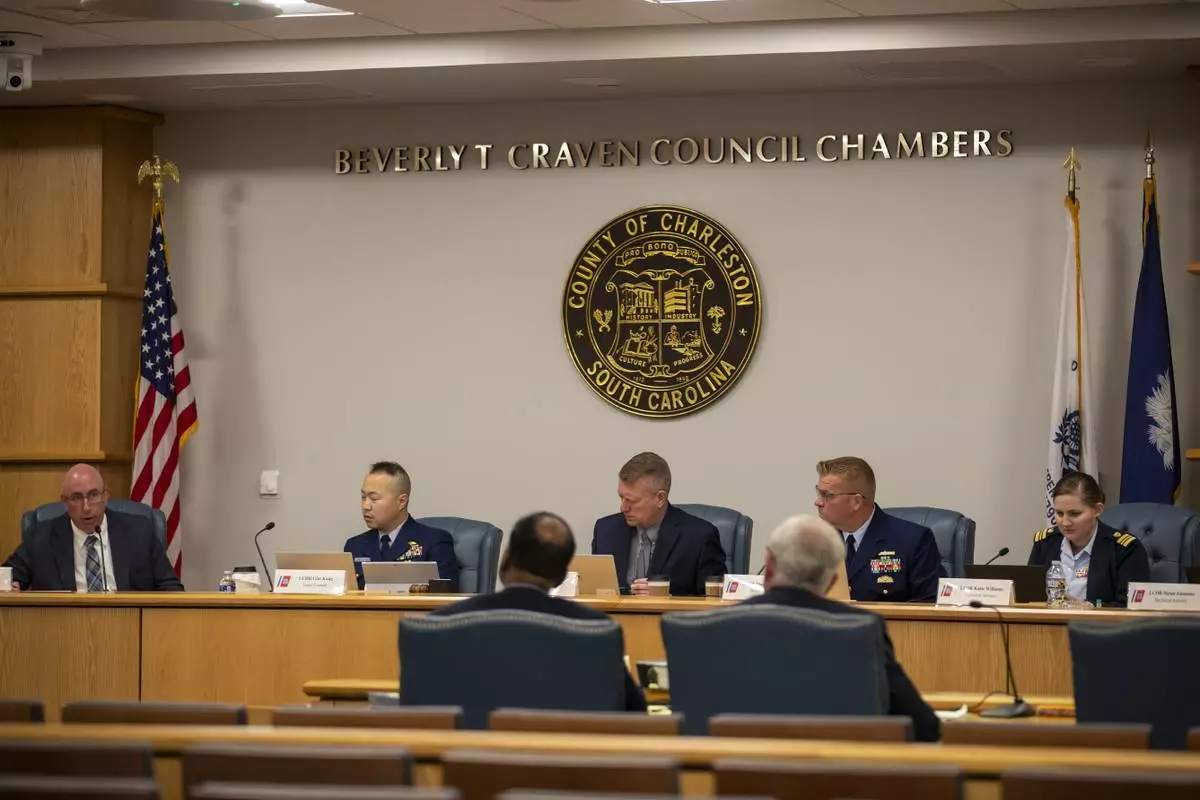

Don Kramer, National Transportation Safety Board engineer, right, testifies Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024, at the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hearing into the June 2023 loss of the Titan submersible, in North Charleston, S.C. (Petty Officer 2nd Class Kate Kilroy/U.S. Coast Guard via AP, Pool)

Don Kramer, National Transportation Safety Board engineer, right, testifies Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024, at the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hearing into the June 2023 loss of the Titan submersible, in North Charleston, S.C. (Petty Officer 2nd Class Kate Kilroy/U.S. Coast Guard via AP, Pool)

Don Kramer, National Transportation Safety Board engineer, testifies Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024, at the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hearing into the June 2023 loss of the Titan submersible, in North Charleston, S.C. (Petty Officer 2nd Class Kate Kilroy/U.S. Coast Guard via AP, Pool)

Don Kramer, National Transportation Safety Board engineer, right, testifies Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024, at the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Board of Investigation hearing into the June 2023 loss of the Titan submersible, in North Charleston, S.C. (Petty Officer 2nd Class Kate Kilroy/U.S. Coast Guard via AP, Pool)

Gim Kang, special counsel for the Coast Guard's Titan Submersible Marine Board of Investigation, listens during the formal hearing inside the Charleston County Council Chambers, Monday, Sept. 23, 2024, in North Charleston, S.C. (Laura Bilson/The Post And Courier via AP, Pool)

In a still from from a video animation provided by the United States Coast Guard an illustration of the Titan submersible, right, is shown near the ocean floor of the Atlantic Ocean, as June 18, 2023 communications between the submersible and the support vessel Polar Prince, not shown, are represented at left. (United States Coast Guard via AP)

Members of the Coast Guard's Titan Submersible Marine Board of Investigation listen during the formal hearing inside the Charleston County Council Chambers, Monday, Sept. 23, 2024, in North Charleston, S.C. (Laura Bilson/The Post And Courier via AP, Pool)

NASA, Boeing and Coast Guard representatives to testify about implosion of Titan submersible

NASA, Boeing and Coast Guard representatives to testify about implosion of Titan submersible

This June 2023 image provided by Pelagic Research Services shows remains of the Titan submersible on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. (Pelagic Research Services via AP)