Three weeks after being asked to modify a $2.78 billion deal that would dramatically change college sports, attorneys excised the word “booster” from the mammoth plan in hopes of satisfying a judge’s concerns about the landmark settlement designed to pay players some of the money they help produce.

As expected, the changes filed in court Thursday did not amount to an overhaul -- replacing “booster” with the term “associated entity or individual,” was the headliner – but the hope is that it will clear the way for U.S District Judge Claudia Wilken to give the settlement agreement preliminary approval.

The new language and replacing of the hazily defined “booster,” which has played a big role in the NCAA's rulebook for decades, is designed to better outline which sort of deals will come under scrutiny under the new rules.

Under terms of the settlement, the biggest schools would have a pool of about $21..5 million in the first year to distribute to athletes via a revenue-sharing plan, but the athletes would still be able to cut name, image and likeness deals with outside groups.

It was the oversight of those deals that was at the heart of Wilken's concerns in the proposed settlement. Many leaders in college sports believe calling something a NIL deal obscures the fact that some contracts are basically boosters paying athletes to play, which is forbidden.

The settlement tries to deal with that problem. By changing “booster” to “associated entity,” then clearly defining what those entities are, the lawyers hope they will address that issue.

The NCAA said in a statement that the new language will “provide both clarity and transparency to those seeking to offer or accept NIL deals.”

The new filing explained that “associated entity or individual” is a “narrower, more targeted, and objectively defined category that does not automatically sweep in ‘today’s third-party donor' or a former student-athlete who wishes to continue to support his/her alma mater.”

Those entities will not include third parties like shoe companies or people who provide less than $50,000 to a school — someone who would be considered a small-money donor. Deals involving “associated entities” will be subject to oversight by a neutral arbitrator, not the NCAA.

In a news release, plaintiffs' attorney Steve Berman focused on how the settlement, and now the new language, restricts how much oversight the NCAA — already sharply muzzled by a series of losses in court — will have on NIL deals.

“The filed settlement terms today constitute a substantial improvement on the current status quo under which a much broader set of deals are prohibited under NCAA rules, and all discipline is carried out by the NCAA without any neutral arbitration or external checks," Berman said.

There is no timetable for Wilken to let the parties know whether they changes they made will be enough for her to sign off on the deal.

The lawyers kept to their word that they would not make dramatic changes to the proposal, but rather clarify for the judge that most third-party NIL deals would still be available to college athletes. On top of that, athletes will also receive billions in revenue annually from their schools through the revenue-sharing plan.

College sports leaders believe unregulated third-party deals through booster-funded organizations known as NIL collective will allow schools to circumvent the cap.

So-called NIL collectives have become the No. 1 way college athletes can cash in on use of their fame. According to Opendorse, a company that provides NIL services to dozens of schools, 81% of the $1.17 billion spent last year on NIL deals with college athletes came from collectives.

Wilken took some issue with the cap — set at $21.5 million for the first year — but it was the plan to subject certain NIL deals to an external review for fair-market value drew the most scrutiny.

AP College Sports Writer Ralph Russo contributed.

Washington quarterback Will Rogers walks on the field near a Big Ten logo during the first half of an NCAA college football game against Northwestern, Saturday, Sept. 21, 2024, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

CHARLESTON, W.Va. (AP) — For decades, Jeff Card's family company was known for manufacturing the once ubiquitous tin boxes where people could buy newspapers on the street.

Today, reach into one of his containers and you may find something entirely different and free of charge: Naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug.

Naloxone distribution containers have been proliferating across the country in the more than a year since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved its sale without a prescription. Naloxone, a nasal spray most commonly known as Narcan, is used as an emergency treatment to reverse drug overdoses.

Such boxes — appearing in neighborhoods, in front of hospitals, health departments and convenience stores — are one way those supporting people with substance use disorder have sought to make Narcan, which can cost around $50 over the counter, accessible to those who need it most. Not unlike little free libraries that distribute books to anyone who wants one, the metal boxes used formerly as newspaper receptacles aren’t locked and don’t require payment. People can take as much as they think they need.

Advocates say the containers help normalize the medication — and are evidence of steadily reducing stigma around its use.

Sixty Narcan receptacles were distributed across 35 states in honor of Thursday's “Save a Life Day” — a naloxone distribution and education event started by a West Virginia nonprofit in 2020. Containers were purchased from Card's Texas-based Mechanism Exchange & Repair, which still serves newspaper customers but has expanded to manufacturing other products amid the newspaper industry's decline.

“It’s fortunate and unfortunate,” said Card, who started making the Narcan containers over two years ago. "Fortunate for us that we’ve got something to build, but unfortunate that this is what we have to build, given how bad the drug problem is in America.”

Opioid deaths were already at record levels before the coronavirus pandemic, but they skyrocketed when it hit in early 2020. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated there were about 85,000 opioid-related deaths in the 12 months that ended in April 2023. But since then, they fell. The CDC estimate for the 12 months that ended in April 2024 was 75,000 -- still higher than any point before the pandemic.

The reasons for the decline are not fully understood. But it does coincide with Narcan, a medication that’s been hard to get in some communities, becoming available over the counter, as well as with the ramping up of spending of funds from legal settlements between governments and drugmakers, wholesalers and pharmacies.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved use of Narcan to treat overdoses back in 1971, but its use was confined to paramedics and hospitals for decades. Narcan nasal spray was first approved by the FDA in 2015 as a prescription drug, and in March, it was approved for over-the-counter sales and started being available last September at major pharmacies.

“That took the barriers away. And that’s when we realized, ‘OK, now we need to increase access. How can we get naloxone into the communities?’” said Caroline Wilson, a West Virginia social worker and person in recovery who coordinated this year's Save a Life Day.

Last year, all 13 states in Appalachia participated in the day spearheaded by West Virginia nonprofit Solutions Oriented Addiction Response. Community organizations in hundreds of counties table in parking lots, outside churches and clinics handing out Narcan and fentanyl test strips and training people on how to use it. They also work to educate the public on myths surrounding the medication, including that it's unsafe to have in easily accessible places. Narcan has no effect on people who use it without opioids in their system.

This year, with the effort expanding to 35 states and a theme of “naloxone everywhere”, the group sent out 2,000 emergency kits containing one Narcan dose to be placed in locations like convenience store bathrooms or parks. The 60 tin newspaper boxes — which sell for around $350 apiece — were purchased with grants.

Aonya Kendrick Barnett's harm reduction coalition Safe Streets Wichita installed one of the Kansas' first Narcan receptacles — which she refers to as “nalox-boxes” — in February. The boxes, now sold by a few different companies, can look different, too. Some look like newspaper boxes, while others look like vending machines.

Since installing a vending machine Narcan container — which just requires a zip code be entered on the keypad to access the medication — it's distributed around 2,600 packages a month.

“To say, ‘Hey, we have a 24-hour vending machine, come over here and come get what you need — no judgment,’ is so bold in this Bible belt state and it’s helping me break down the the stigma," she said.

Kendrick Barnett said there's no place for judgment when it comes to what she calls live-saving health care: “People are going to use drugs. It’s not our job to condemn or condone it. It’s our job to make sure that they have the necessary health care that they need to survive.”

The Save a Life Day box her organization received is going to go in front of their new clinic, scheduled to open in October.

In Erie, Pennsylvania, 74-year-old stained glass artist Larry Tuite said he grew concerned seeing overdoses increasing in his city. He began leaving Narcan packages on the windowsills of 24-hour markets in town that sell products like pipes and rolling papers. He was shocked at how quickly they disappeared.

“As many as I give out, I run through them really quickly," said Tuite, who keeps cases of the drugs stacked along the walls of his studio apartment.

The Save a Life Day container, which he got permission to put outside one such store, has helped him to disperse even more Narcan. At least a dozen people have been saved by the medication he's distributed, he said.

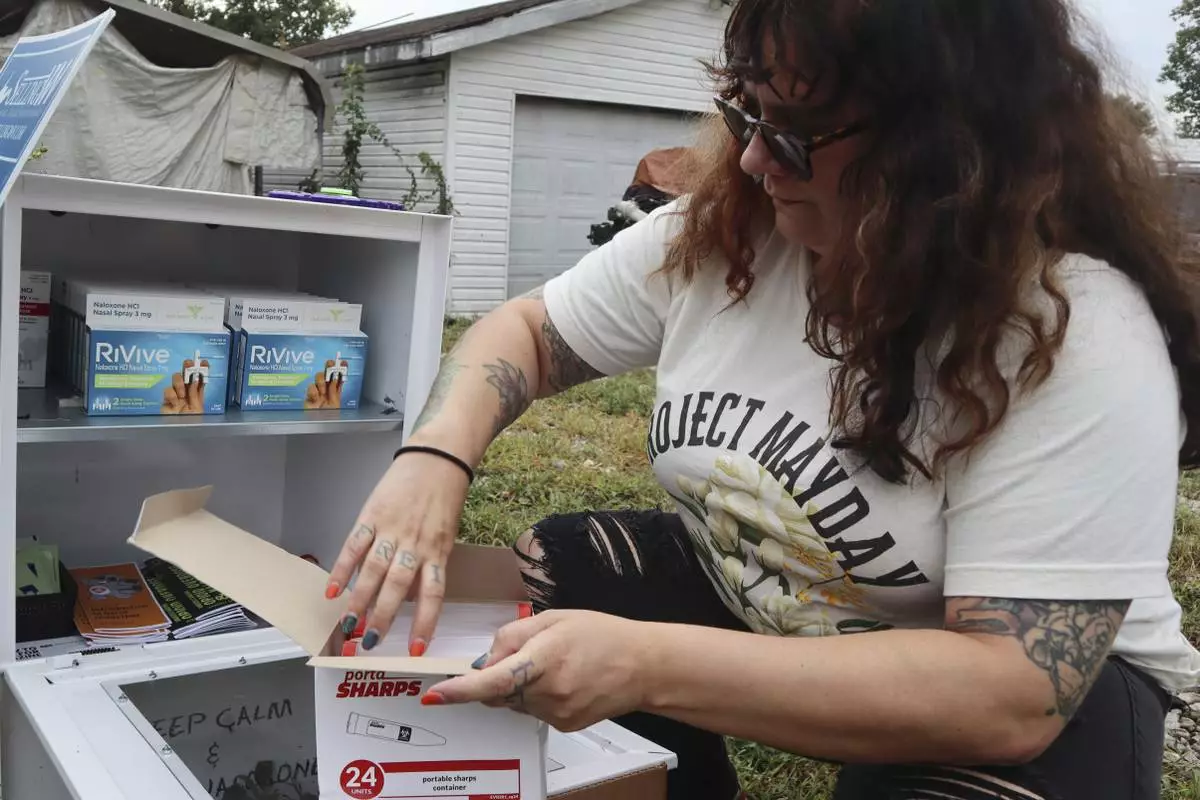

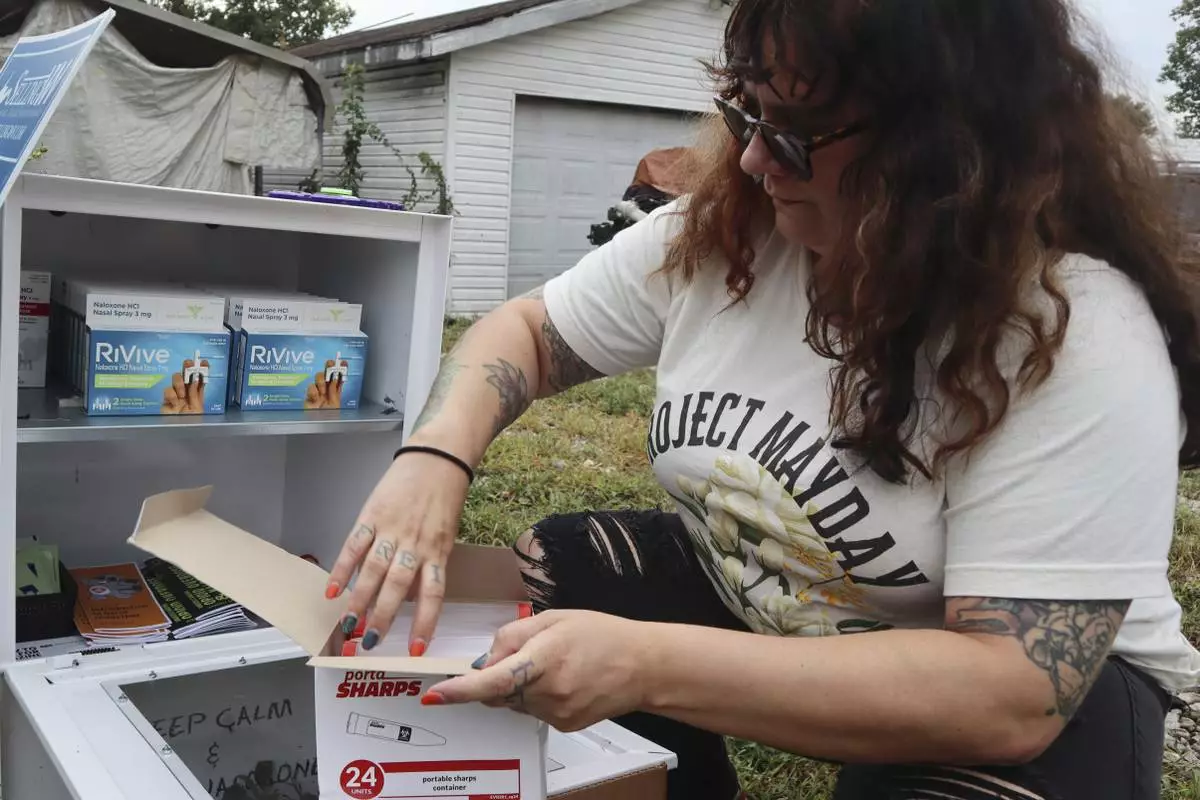

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery who runs a harm reduction coalition based out of Putnam County, West Virginia, said Narcan wasn't something she ever had access to when she was using opioids.

“People can just reach in and grab what they need — we didn't have that back then,” she said, while stocking a container in a residential neighborhood earlier this week. “To actually see that there is some access now — I’m glad that we’ve at least moved forward a little bit in that direction."

AP journalist Geoff Mulvihill contributed to this report.

A new naloxone distribution box sits in a residential neighborhood in Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residential neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

A new naloxone distribution box sits in a residential neighborhood in Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)

Tasha Withrow, a person in recovery and co-founder of harm reduction organization Project Mayday, refills a new naloxone distribution box in a residental neighborhood of Hurricane, W.Va. on Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Leah Willingham)