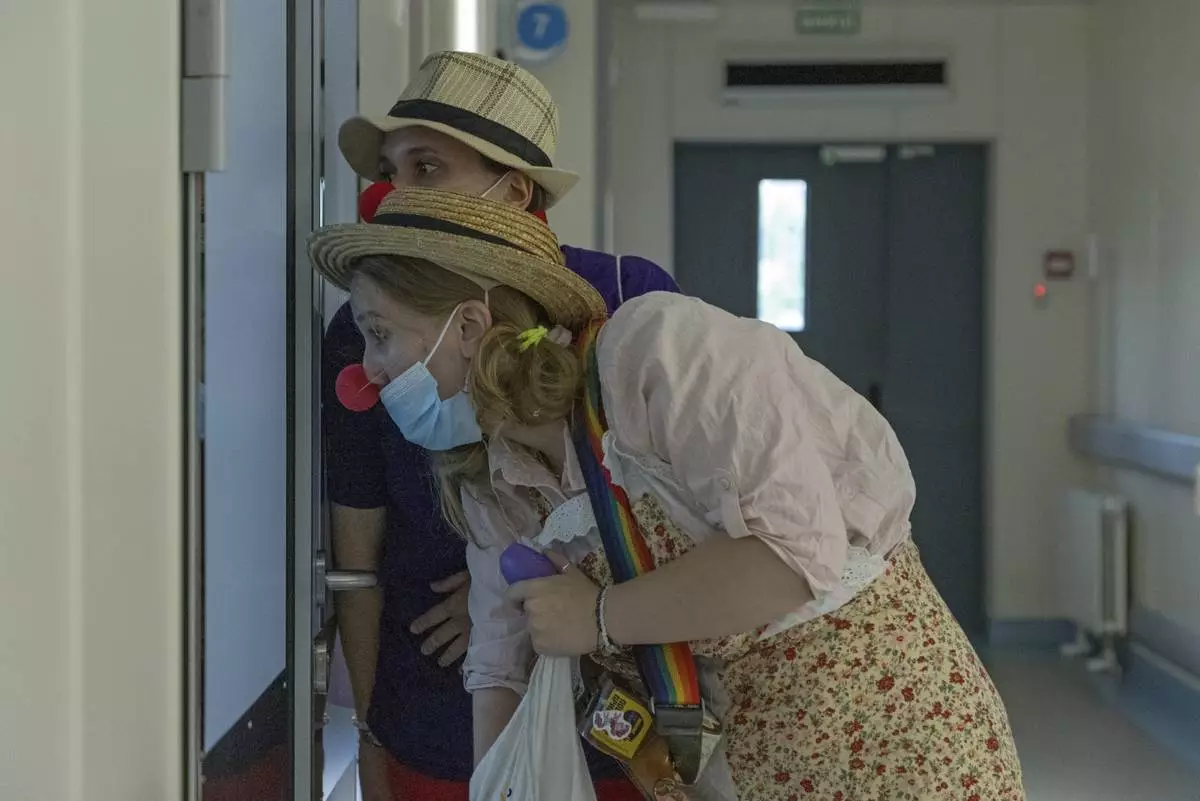

KYIV, Ukraine (AP) — Their costumes are put on with surgical precision: Floppy hats, foam noses, bright clothes, and a ukulele with multicolored nylon strings.

Moments later, in a beige hospital ward normally filled with the beeping sounds of medical machinery, there are bursts of giggles and silly singing.

As Ukraine’s medical facilities come under pressure from intensifying attacks in the war against Russia's full-scale invasion, volunteer hospital clowns are duck-footing their way in to provide some badly needed moments of joy for hospitalized children.

The “Bureau of Smiles and Support” (BUP) is a hospital clowning initiative established in 2023 by Olha Bulkina, 35, and Maryna Berdar, 39, who already had more than five years of hospital clowning experience between them. “Our mission is to let childhood continue regardless of the circumstances,” Bulkina, told The Associated Press.

BUP took on new significance following a Russian missile strike on Okhmatdyt Children’s Hospital in Kyiv in July. The attack on Ukraine’s largest pediatric facility forced the evacuation of dozens of young patients, including those with cancer, to other hospitals in the capital – and the clowns did not stand aside.

Together with first responders, Berdar and Bulkina helped with clearing the rubble after the attack and attended to the children who were relocated to other medical facilities. But even for them, the real heroes there were young patients.

“When the children were evacuated from Okhmatdyt after the missile attack, many of them were in extremely difficult medical conditions, but even in this situation they tried to support the adults,” said Berdar, recalling the events after the strike.

The hospital clowns, who use traditional clown noses and bright costumes, are now visiting multiple hospitals in the Ukrainian capital region, including the National Cancer Institute, where patient numbers have surged after the Okhmatdyt attack.

Tetiana Nosova, 22, and Vladyslava Kulinich, 22, are volunteer hospital clowns who go by Zhuzha and Lala and joined BUP more than a year ago. For them, hospital clowning is as challenging as it is rewarding.

“I volunteer so that children don’t think about their illness, even for a short moment, so that laughter replaces tears, and joy replaces fear, especially during medical procedures,” Kulinich said. In her practice, she stays together with children, sharing all their feelings, whether they are fear, pain, or joy.

For Nosova, the process itself is what made her start clowning. “I am motivated by joy. I simply enjoy it. All my life I studied to be an actress, all my life I enjoyed making people laugh. That’s enough motivation for me," she said.

In a city grappling with nightly air raid alerts and power outages, overworked doctors say the presence of the volunteers brings a much-needed distraction, often helping children who had been undergoing painful medical treatment to feel happy again.

“Clowns play a very important role in the treatment of children. They help distract the children, they help them forget about the pain, they help them not pay attention to the nurses or doctors who come to treat them,” Valentyna Mariash, a senior nurse on the Okhmatdyt cancer ward, told AP.

The July attack complicated treatment plans for many families. Daria Vertetska, 34, was in Okhmatdyt with her 7-year-old daughter, Kira, when the missile exploded just outside their ward. Kira, who was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma of the nasopharynx, was asleep, medicated with morphine.

“It saved her that she was covered with a blanket during the strike, but still, her head, legs, and arms were cut with small glass shards,” said Vertetska. She and Kira returned to Okhmatdyt in less than a week after the attack.

Not all the children returned to the hospital. Some stayed in the medical facilities where they had been evacuated, while others were moved to apartments paid for by charity organizations and located in the hospital’s vicinity.

Despite hospital clown initiatives like BUP across Ukraine, the need for their work grows exponentially. “When I see how our work is needed in the large children’s hospitals located in Kyiv, I can only imagine what a great need there is in regional and district hospitals, where such (clown) activity, as for example in Okhmatdyt, to be honest, simply does not exist,” Berdar said.

The World Health Organization, earlier this month, warned that the country faces a deepening public health crisis, largely due to devastating missile and drone strikes on the country’s electricity system as well as hospital infrastructure.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, WHO has recorded nearly 2,000 attacks on Ukraine’s health care facilities and says they are having a severe impact.

Children are among the most vulnerable, but a mental health crisis affects the whole country. It means the clowns’ work has won broad support from medical professionals.

Parents are simply happy to see a smile return to their children’s faces.

“With clowns, children learn to joke, they play with soap bubbles, their mood lifts. Today, Kira saw clowns playing the ukulele, now she wants one, too,” said her mother, Daria.

Associated Press writer Derek Gatopoulos contributed to this report.

Follow AP's coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/russia-ukraine

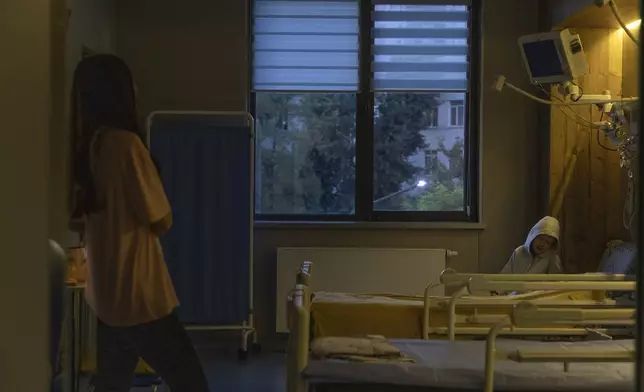

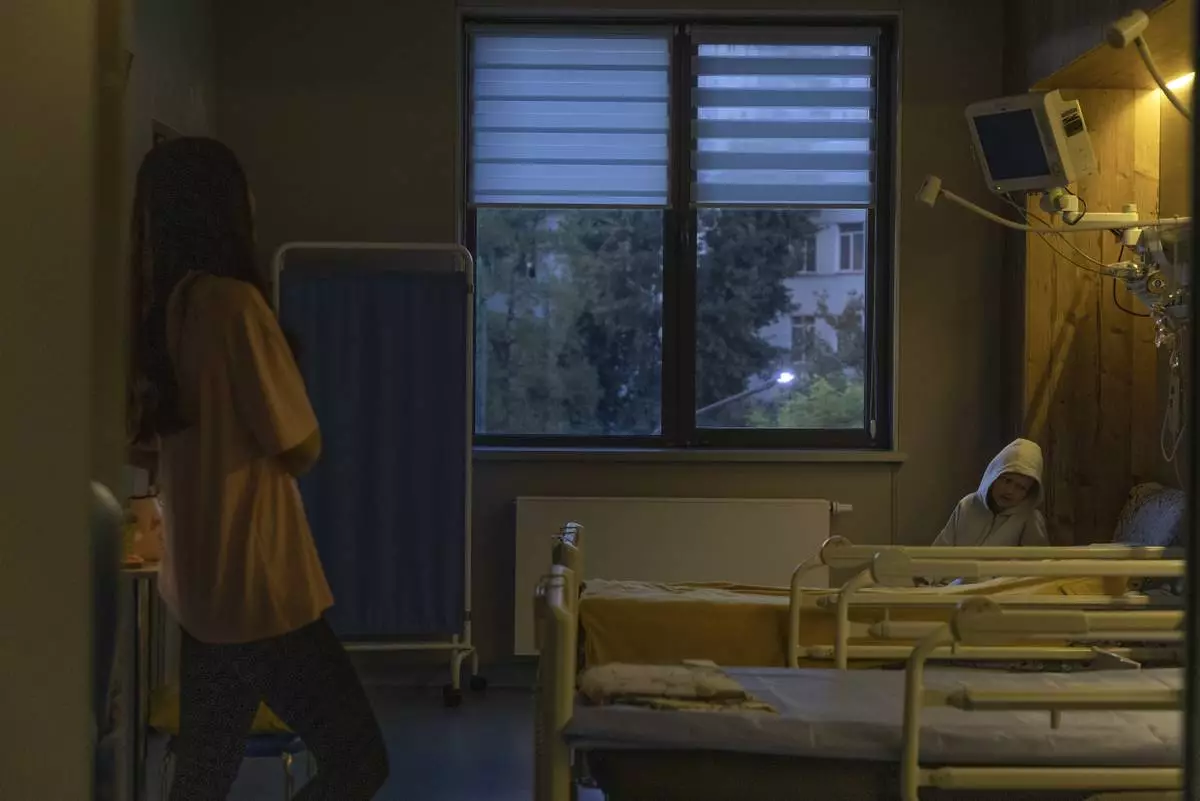

Kira Vertetska, 8 and her mother Daria inside their room at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Kira Vertetska, 8 and her mother Daria pose for a photo in a corridor at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

FILE - Rescuers work together to clear debris during a search operation for survivors at the Okhmatdyt children's hospital that was hit by a Russian missile, in Kyiv, Ukraine, July 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka, File)

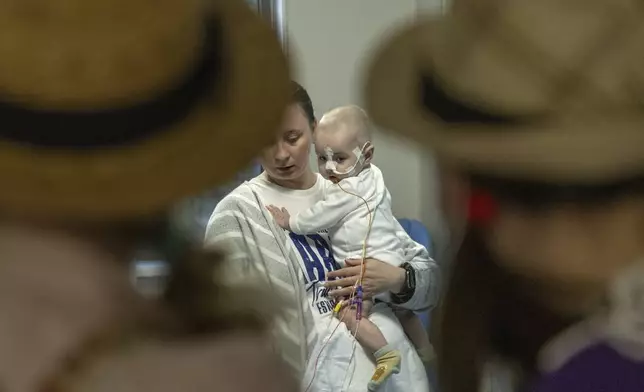

Michael Bilyk, is held by his mother Antonina Malyshko, as he is visited by Zhuzha and Lala from the volunteer group the "Bureau of Smiles and Support" at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

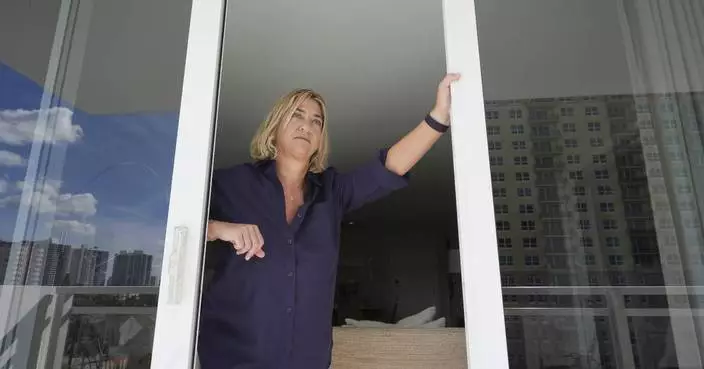

Maryna Berdar, 39, co-founder of the "Bureau of Smiles and Support" sits in front of Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine Saturday Sept. 14, 2024 which was destroyed after a Russian missile strike on July 8. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Tetiana Nosova, who goes by the clown name of Zhuzha, a volunteer from the "Bureau of Smiles and Support" watches as Kira Vertetska, 8, plays a ukulele at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

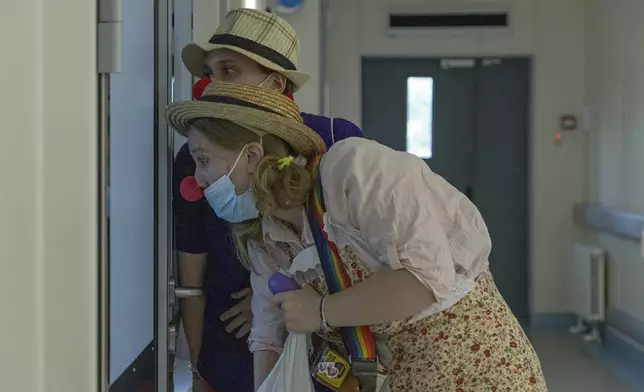

Vladyslava Kulinich, right, Tetiana Nosova, who have the clown names Lala and Zhuzha, pose for a photo as they prepare to perform at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

FILE - Rescuers, medical staff and volunteers clean up the rubble and search for victims after a Russian missile hit the country's main children's hospital Okhmatdyt in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, July 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka, File)

Kira Vertetska, 8, who is undergoing treatment in the oncology department at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, paints a clay figure Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Olha Bulkina, 35, co-founder of the "Bureau of Smiles and Support" sits in front of Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine Saturday Sept. 14, 2024 which was destroyed after a Russian missile strike on July 8. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Vladyslava Kulinich, rear, and Tetiana Nosova, who have the clown names Lala and Zhuzha, prepare to perform at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

A view of the damage to Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine Saturday Sept. 14, 2024 which was destroyed after a Russian missile strike on July 8. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Kira Vertetska, 8, who is undergoing treatment in the oncology department at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, paints a clay figure, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

FILE - Emergency workers remove rubble and look for survivors at the site of Okhmatdyt children's hospital hit by Russian missiles, in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, July 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka, File)

FILE - Emergency workers respond at the Okhmatdyt children's hospital hit by Russian missiles, in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, July 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Alex Babenko, File)

Vladyslava Kulinich, right, Tetiana Nosova, who have the clown names Lala and Zhuzha, prepare to perform at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Vladyslava Kulinich, right, Tetiana Nosova, who have the clown names Lala and Zhuzha, prepare to perform at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Olha Bulkina, 35, co-founder of the "Bureau of Smiles and Support" sits in front of Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine Saturday Sept. 14, 2024 which was destroyed after a Russian missile strike on July 8. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)

Tetiana Nosova, who goes by the clown name of Zhuzha, a volunteer from the "Bureau of Smiles and Support" plays a ukulele as she stands with Michael Bilyk, who is held by his mother Antonina Malyshko, and Kira Vertetska, 8, at Okhmatdyt children's hospital in Kyiv, Ukraine, Thursday Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton Shtuka)