A stretch of aqueduct that supplies about half of New York City's water is being shut down through the winter as part of a $2 billion project to address massive leaks beneath the Hudson River.

The temporary shutdown of the Delaware Aqueduct in upstate New York has been in the works for years, with officials steadily boosting capacity from other parts of the city's sprawling 19-reservoir system. Water will flow uninterrupted from city faucets after the shutdown begins this week, officials said, though its famously crisp taste might be affected as other sources are tapped into more heavily.

“The water will alway be there,” Paul Rush, deputy commissioner for the city’s Department of Environmental Protection. “We’re going to be changing the mix of water that consumers get.”

The Delaware Aqueduct is the longest tunnel in the world and carries water for 85 miles (137 kilometers) from four reservoirs in the Catskill region to other reservoirs in the city's northern suburbs. Operating since 1944, it provides roughly half of the 1.1 billion gallons (4.2 billion liters) a day used by more than 8 million New York City residents. The system also serves some upstate municipalities.

But the aqueduct leaks up to 35 million gallons (132 million liters) of water a day, nearly all of it from a section far below the Hudson River.

The profuse leakage has been known about for decades, but city officials faced a quandary: they could not take the critical aqueduct offline for years to repair the tunnel. So instead, they began constructing a parallel 2.5-mile (4-kilometer) bypass tunnel under the river about a decade ago.

The new tunnel will be connected during the shut down, which is expected to last up to eight months. More than 40 miles (64 kilometers) of the aqueduct running down from the four upstate reservoirs will be out of service during that time, though a section closer to the city will remain in use.

Other leaks farther north in the aqueduct also will be repaired in the coming months.

Rush said the work was timed to avoid summer months, when demand is higher. The city also has spent years making improvements to other parts of the system, some of which are more than 100 years old.

“There’s a lot of work done thinking about where the alternate supply would come from,” Rush said.

Capacity has been increased for the complementary Catskill Aqueduct and more drinking water will come from the dozen reservoirs and three lakes of the Croton Watershed in the city's northern suburbs.

The heavier reliance on those suburban reservoirs could affect the taste of water due to a higher presence of minerals and algae in the Croton system, according to city officials.

“While some residents may notice a temporary, subtle difference in taste or aroma during the repairs, changes in taste don’t mean something is wrong with the water," DEP Commissioner Rohit Aggarwala said in a prepared statement. "Just like different brands of bottled water taste a bit different, so do our different reservoirs.”

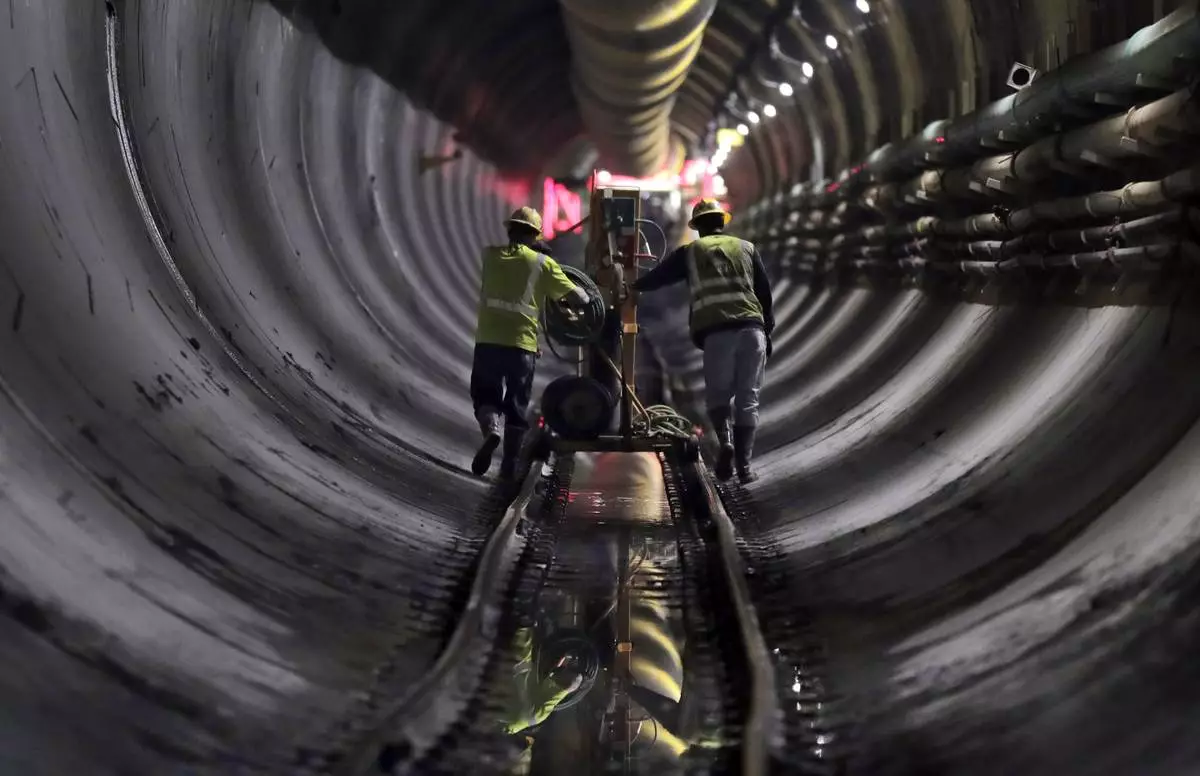

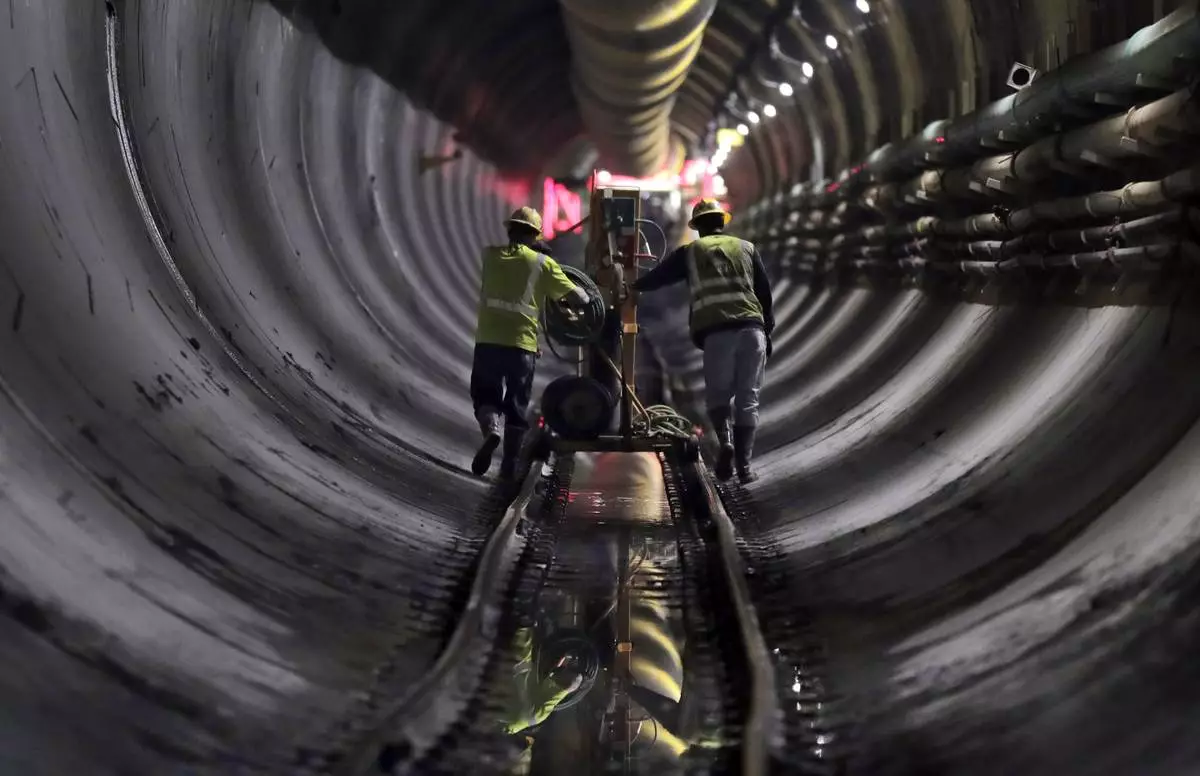

FILE - Tunnel workers push equipment up a rail track to a machine boring a 2.5-mile bypass tunnel for the Delaware Aqueduct in Marlboro, N.Y., May 16, 2018. (AP Photo/Julie Jacobson, File)

BANGKOK (AP) — A new investigation focused on three of the world’s largest producers of shrimp released on Monday claims that as big Western supermarkets make windfall profits, their aggressive pursuit of ever-lower wholesale prices is causing misery for people at the bottom end of the supply chain.

The regional analysis of the industry in Vietnam, Indonesia and India, which provide about half the shrimp in the world’s top four markets — the United States, European Union, United Kingdom and Japan — is based on research done by an alliance of NGOs. It found a 20%-60% drop in earnings from pre-pandemic levels as producers struggle to meet pricing demands by cutting labor costs.

In many places this has meant unpaid and underpaid work through longer hours, wage insecurity as rates fluctuate, and many workers not even making low minimum wages.

Supermarkets linked to facilities where exploited labor was reported by workers include Target, Walmart and Costco in the United States, Britain’s Sainsbury’s and Tesco, and Aldi and Co-op in Europe.

The regional report brought together more than 500 interviews conducted in-person with workers in their native languages, in India, Indonesia and Vietnam — published separately as country-specific reports — supplemented with secondary data and interviews from Thailand, Bangladesh and Ecuador.

In Vietnam, Hawaii-based Sustainability Incubator investigators found that the workers who peel, gut and devein shrimp typically work six or seven days a week, often in rooms kept extremely cold to keep the product fresh.

Some 80% of those involved in processing shrimp are women, many of whom rise at 4 a.m. and return home at 6 p.m. Pregnant women and new mothers can stop one hour earlier, the report found.

In India, researchers from the Corporate Accountability Lab found that workers face “dangerous and abusive conditions.” Highly salinated water from newly dug hatcheries and ponds, tainted with chemicals and toxic algae, also contaminate surrounding water and soil.

Unpaid labor prevails, including salaries below minimum wage, unpaid overtime, wage deductions for costs of work and “significant” debt bondage, the report found. Child labor was also found, with girls aged 14 and 15 being recruited for peeling work.

In Indonesia, three non-profit research organizations found that wages have fallen since the COVID-19 pandemic and today average $160 per month for shrimp workers, below Indonesia’s minimum wage in most of the biggest shrimp-producing provinces. Shrimp peelers routinely are required to work at least 12 hours per day to meet minimum targets.

Switzerland’s Co-op said it had a “zero tolerance” policy for labor law violations and that its producers “receive fair and market-driven prices.”

Germany’s Aldi did not specifically address the issue of pricing, but said it uses independent certification schemes to ensure responsibly sourcing for farmed shrimp products, and would continue to monitor the allegations.

“We are committed to fulfilling our responsibility to respect human rights,” Aldi said.

Sainsbury’s referred to a comment from the British Retail Consortium industry group, which said its members were committed to sourcing products at a “fair, sustainable price” and that the welfare of people and communities in supply chains is fundamental to their purchasing practices.

The Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers issued a statement calling the allegations in the report “unfounded, misleading and detrimental to the reputation of Vietnam’s shrimp exports,” citing government labor policies.

The NGO's report stresses that using middlemen to buy the shrimp obfuscates the true sources of shrimp that appear in western supermarkets, so many retailers may not be following ethical commitments they’ve made about procuring shrimp.

Only about 1,000 of the 2 million shrimp farms in the major producing countries are certified by either the Aquaculture Stewardship Council or the Best Aquaculture Practices ecolabel, making it "mathematically impossible for certified farms to produce enough shrimp per month to supply all of the supermarkets that boast commitments to purchasing certified shrimp,” the report says.

U.S. policymakers could use antitrust and other laws already in place to establish oversight to ensure fair pricing from western retailers, rather than imposing punishing tariffs on suppliers, says Katrin Nakamura of Sustainability Incubator, who wrote the regional report.

In July, the European Union adopted a new directive requiring companies to “identify and address adverse human rights and environmental impacts of their actions inside and outside Europe.”

Officials from Indonesia and Vietnam have met with the report's authors to discuss their findings and look for solutions.

Given the current disparity in retail and wholesale prices, paying more to farmers would not have to mean higher prices for consumers, the Sustainability Incubator report said, but it would mean lower profits for the supermarkets.

“Labor exploitation in shrimp aquaculture industries is not company, sector, or country-specific,” the report concludes. “Instead, it is the result of a hidden business model that exploits people for profit.”

This story was supported by funding from the Walton Family Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Yulius Cahyonugroho poses for a photo at his shrimp farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers sort shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Centra Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm worker Dias Yudho Prihantoro, left, harvests shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm worker Andika Yudha Agusta feed shrimps at a shrimp farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers harvest shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)