WASHINGTON (AP) — Republicans are pointing to newly released immigration enforcement data to bolster their argument that the Biden administration is letting migrants who have committed serious crimes go free in the U.S. But the numbers have been misconstrued without key context.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement released data to Republican Rep. Tony Gonzales in response to a request he made for information about people under ICE supervision either convicted of crimes or facing criminal charges. Gonzales' Texas district includes an 800-mile stretch bordering Mexico.

Gonzales posted the numbers online and they immediately became a flashpoint in the presidential campaign between former President Donald Trump, who has vowed to carry out mass deportations, and Vice President Kamala Harris. Immigration — and the Biden administration's record on border security — has become a key issue in the election.

Here's a look at the data and what it does or doesn't show:

As of July 21, ICE said 662,556 people under its supervision were either convicted of crimes or face criminal charges. Nearly 15,000 were in its custody, but the vast majority — 647,572 — were not.

Included in the figures of people not detained by ICE were people found guilty of very serious crimes: 13,099 for homicide, 15,811 for sexual assault, 13,423 for weapons offenses and 2,663 for stolen vehicles. The single biggest category was for traffic-related offenses at 77,074, followed by assault at 62,231 and dangerous drugs at 56,533.

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, later clarified that the numbers span decades and those not in its custody may be held by a state or local agency. For example, someone serving time in a state prison for murder could be counted as a criminal not in ICE’s custody. They are not being held by federal immigration authorities but they are detained — a distinction ICE didn’t make in its report to Gonzales.

Millions of people are on ICE's “non-detained docket,” or people under the agency's supervision who aren't in its custody. Many are awaiting outcomes of their cases in immigration court, including some wearing monitoring devices. Others have been released after completing their prison sentences because their countries won’t take them back.

Republicans pointed to the data as proof that the Biden administration is letting immigrants with criminal records into the country and isn't doing enough to kick out those who commit crimes while they're here.

“The truth is clear — illegal immigrants with a criminal record are coming into our country. The data released by ICE is beyond disturbing, and it should be a wake-up call for the Biden-Harris administration and cities across the country that hide behind sanctuary policies,” Gonzales said in a news release, referring to pledges by local officials to limit their cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

Trump, who has repeatedly portrayed immigrants as bringing lawlessness and crime to America, tweeted multiple screenshots of the data with the words: “13,000 CROSSED THE BORDER WITH MURDER CONVICTIONS.”

He also asserted that the numbers correspond to Biden and Harris' time in office.

The data was being misinterpreted, Homeland Security said in a statement Sunday.

“The data goes back decades; it includes individuals who entered the country over the past 40 years or more, the vast majority of whose custody determination was made long before this Administration,” the agency said. "It also includes many who are under the jurisdiction or currently incarcerated by federal, state or local law enforcement partners.”

The department also stressed what it has done to deport those without the right to stay in America, saying it had removed or returned more than 700,000 people in the past year, which it said was the highest number since 2010. Homeland Security said it had removed 180,000 people with criminal convictions since President Joe Biden took office.

The data isn’t only listing people who entered the country during the Biden administration but includes people going back decades who came during previous administrations, said Doris Meissner, former commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, which was the predecessor to ICE.

They’re accused or convicted of committing crimes in America as opposed to committing crimes in other countries and then entering the U.S., said Meissner, who is now director of the U.S. Immigration Policy Program at the Migration Policy Institute.

“This is not something that is a function of what the Biden administration did,” she said. “Certainly, this includes the Biden years, but this is an accumulation of many years, and certainly going back to at least 2010, 2011, 2012.”

A 2017 report by Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General says that as of August 2016, ICE had about 368,574 people on its non-detained docket who were convicted criminals. By June 2021, that number was up to 405,786.

ICE has limited resources. The number of people it supervises has skyrocketed, while its staffing has not. As the agency noted in a 2023 end-of-year report, it often has to send staff to help at the border, taking them away from their normal duties.

The number of people ICE supervises but who aren't in its custody has grown from 3.3 million a little before Biden took office to a little over 7 million last spring.

"The simple answer is that as a system, we haven’t devoted enough resources to the parts of the government that deal with monitoring and ultimately removing people who are deportable," Meissner said.

ICE also has logistical and legal limits on who they can hold. Its budget allows the agency to hold 41,500 people at a time. John Sandweg, who was acting ICE director from 2013 to 2014 under then-President Barack Obama, said holding people accused or convicted of the most serious crimes is always the top priority.

But once someone has a final order of removal — meaning a court has found that they don't have the right to stay in the country — they cannot be held in detention forever while ICE works out how to get them home. A 2001 Supreme Court ruling essentially prevented ICE from holding those people for more than six months if there is no reasonable chance to expect they can be sent back.

Not every country is willing to take back their citizens, Sandweg said.

He said he suspects that a large number of those convicted of homicide but not held by ICE are people who were ordered deported but the agency can't remove them because their home country won't take them back.

“It’s a very common scenario. Even amongst the countries that take people back, they can be very selective about who they take back,” he said.

The U.S. also could run into problems deporting people to countries with which it has tepid relations.

Homeland Security did not respond to questions about how many countries won't take back their citizens. The 2017 watchdog report put the number at 23 countries, plus an additional 62 that were cooperative but where there were delays getting things like passports or travel documents.

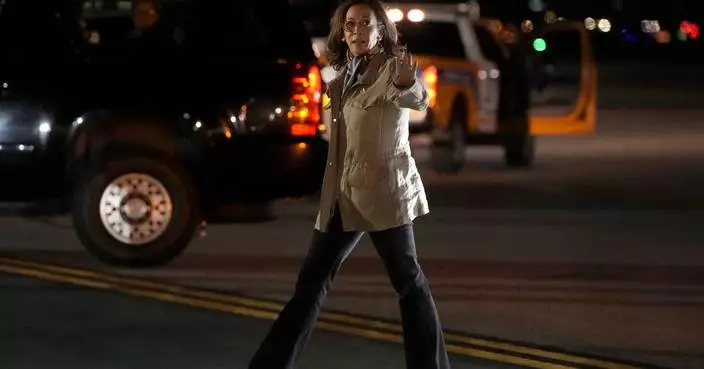

Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris talks with John Modlin, the chief patrol agent for the Tucson Sector of the U.S. Border Patrol, right, and Blaine Bennett, the U.S. Border Patrol Douglas Station border patrol agent in charge, as she visits the U.S. border with Mexico in Douglas, Ariz., Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump dances at a campaign rally at Bayfront Convention Center in Erie, Pa., Sunday, Sept. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Rebecca Droke)

BANGKOK (AP) — Indonesian shrimp farmer Yulius Cahyonugroho operated more than two dozen ponds only a few years ago, employing seven people and making more than enough to support his family.

Since then, the 39-year-old says the prices he gets from purchasers have fallen by half and he's had to scale back to four workers and about one-third the ponds, some months not even breaking even. His wife has had to take a job at a watermelon farm to help support their two children.

“It is more stable than the shrimp farms,” said the farmer from Indonesia’s Central Java province.

As big Western supermarkets make windfall profits, their aggressive pursuit of ever-lower wholesale prices is causing misery for people at the bottom end of the supply chain — people like Cahyonugroho who produce and process the seafood, according to an investigation by an alliance of NGOs focused on three of the world's largest producers of shrimp provided to The Associated Press ahead of its publication Monday.

The analysis of the industry in Vietnam, Indonesia and India, which provide about half the shrimp in the world's top four markets, found a 20%-60% drop in earnings from pre-pandemic levels as producers struggle to meet pricing demands by cutting labor costs.

In many places this has meant unpaid and underpaid work through longer hours, wage insecurity as rates fluctuate, and many workers not even making low minimum wages. The report also found hazardous working conditions, particularly in India and parts of Indonesia, and even child labor in some places in India.

“The supermarket procurement practices changed, and the working conditions were affected — directly and rapidly,” said Katrin Nakamura of Sustainability Incubator, who wrote the regional report and whose Hawaii-based nonprofit led the research on the industry in Vietnam. “Those two things go together because they're tied together through the pricing.”

Tubagus Haeru Rahayu, the director general of aquaculture for Indonesia’s Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Ministry, said he was surprised by the report’s findings and had already reached out to people in the industry to investigate the price pressures.

“If there is pressure like that, there will definitely be a reaction — not only in Indonesia but in Vietnam and India too," he told the AP in an interview at his Jakarta office.

Indian and Vietnamese officials refused to comment.

Supermarkets linked to facilities where exploited labor was reported by workers include Target, Walmart and Costco in the United States, Britain's Sainsbury's and Tesco, and Aldi and Co-op in Europe.

Switzerland's Co-op said it had a “zero tolerance” policy for violations of labor law, and that its producers “receive fair and market-driven prices.”

Germany’s Aldi did not specifically address the issue of pricing, but said it uses independent certification schemes to ensure responsibly sourcing for farmed shrimp products, and would continue to monitor the allegations.

“We are committed to fulfilling our responsibility to respect human rights,” Aldi said.

Sainsbury's referred to a comment from the British Retail Consortium industry group, which said its members were committed to sourcing products at a "fair, sustainable price” and that the welfare of people and communities in supply chains is fundamental to their purchasing practices.

None of the other retailers named in the report responded to multiple requests for comment on the report, titled “Human Rights for Dinner.”

In Vietnam, researchers found that workers who peel, gut and devein shrimp typically work six or seven days a week, often in rooms kept extremely cold to keep the product fresh.

Some 80% of those involved in processing the shrimp are women who rise at 4 a.m. and return home at 6 p.m., with the exception of pregnant women and new mothers who can stop one hour earlier.

“The work day for peelers consists of standing in a refrigerated and disinfected room and working extremely rapidly with a knife while taking care not to make a mistake,” researchers said.

Wages are generally not disclosed ahead of time and are based upon production. Sometimes workers make minimum wage, but frequently they do not.

The Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers issued a statement calling the allegations in the report “unfounded, misleading and detrimental to the reputation of Vietnam’s shrimp exports.”

It cited government labor policies in a four-page statement but did not specifically address the findings, and did not respond to queries.

After food supply chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission reported earlier this year that some grocers have used the situation "as an opportunity to further raise prices to increase their profits, which remain elevated today.”

The demands for lower wholesale shrimp prices — combined with rising production costs and an oversupply — means farmers often must sell their products under cost just to keep operations going, the Sustainability Incubator analysis found.

Cahyonugroho said he's stuck selling his shrimp at the price offered by middlemen who then sell it to factories for processing. He can't scrape together the startup costs needed to sell directly to factories or markets to earn more.

“The opportunity is there,” he said, “but you need a lot of capital if you want to jump into something like that.”

The middlemen who buy the shrimp obfuscate the true sources of shrimp that appear in Western supermarkets, so many retailers may not be following ethical commitments they've made about procuring shrimp.

Only about 1,000 of the 2 million shrimp farms in the major producing countries of India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Ecuador, Thailand and Bangladesh are certified by either the Aquaculture Stewardship Council or the Best Aquaculture Practices ecolabel.

"With the yield from most certified shrimp farms being very small, it is mathematically impossible for certified farms to produce enough shrimp per month to supply all of the supermarkets that boast commitments to purchasing certified shrimp,” the report said.

Ideally, supermarkets should pay higher wholesale prices and ensure that the extra money makes it all the way down the supply chain, Nakamura said.

U.S. policymakers could use antitrust and other laws already in place to establish oversight to ensure fair pricing from Western retailers, rather than adding punishing tariffs on suppliers for labor violations, she said.

Awareness about the trends hurting suppliers is growing.

In July, the European Union adopted a new directive requiring companies to “identify and address adverse human rights and environmental impacts of their actions inside and outside Europe.”

Britain's Groceries Code Adjudicator office published a “deep dive” into views of suppliers about the conduct of supermarkets, saying they had chosen to conduct “warfare” with suppliers.

Higher wholesale prices don't have to mean higher prices for consumers, Sustainability Incubator said.

“Prices to farmers would be at least 200% higher than today if the shrimp sold in Global North supermarkets was made at minimum wage rates and in compliance with applicable domestic laws for labor, workplace health, and safety,” the report said. “This would not necessarily mean higher consumer prices, because supermarkets are already profiting at existing consumer prices.”

Researchers from the Corporate Accountability Lab found that Indian shrimp industry workers face “dangerous and abusive conditions” and that highly-salinated water from newly-dug hatcheries and ponds, tainted with chemicals and toxic algae, are contaminating surrounding water and soil.

Unpaid labor prevails, including salaries below minimum wage, unpaid overtime, wage deductions for costs of work and “significant” debt bondage, the report found.

Child labor was also identified, with girls aged 14 and 15 being recruited for peeling work.

In Indonesia, three non-profit research organizations found that shrimp workers' wages have declined since the pandemic and now average $160 per month, below Indonesia's minimum wage in most of the biggest shrimp-producing provinces. Shrimp peelers were found to be routinely required to work at least 12 hours per day to meet minimum targets.

Still, given widespread poverty most workers said they're happy to have their jobs, said lead researcher Kharisma Nugroho of the Migunani Research Institute.

“It’s exploitation of the vulnerability of the workers, because they have a lack of options,” he said.

“They’re paid the minimum wages but they have to work 150% of the normal,” he told the AP. “Can they live? Yes. Can they move? Yes. Do they make a complaint? No. They’re still there.”

The regional report compiled more than 500 interviews conducted in-person with workers in their native languages, in India, Indonesia and Vietnam, supplemented with secondary data and interviews from Thailand, Bangladesh and Ecuador.

After the Indonesia country report was issued recently, government officials asked to meet with the authors, and Nugroho said they showed a “genuine willingness to improve the situation.”

Vietnamese officials have also engaged with Sustainability Incubator to talk about the findings.

Government and industry intervention has already helped in Thailand, which has been criticized after the AP exposed serious labor abuses in the shrimp industry in the past. That, however, has led to higher prices for Thai shrimp, leading some buyers to shift sourcing to India and Ecuador.

Ecuador has an industrial approach to shrimp farming — unlike the smaller, often family-run operations in Southeast Asia — and is now the world's largest exporter of shrimp. It has the lowest prices, followed by India; China, which wasn't included in the report; then Vietnam and Indonesia.

But with the demand for lower wholesale prices, while Ecuador’s exports rose 12% in volume in 2023, they fell 5% in value. India’s exports rose 1% but dropped nearly 11% in value.

Meantime, with their relatively higher prices, Vietnam's exports were down 25% in 2023 in volume Indonesia's dropped 9.5%.

“Labor exploitation in shrimp aquaculture industries is not company, sector, or country-specific,” the report concluded. “Instead, it is the result of a hidden business model that exploits people for profit.”

AP journalist Edna Tarigan in Jakarta, Indonesia, contributed to this report.

This story was supported by funding from the Walton Family Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Farm worker Dias Yudho Prihantoro, left, harvests shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers prepare a truck loaded with shrimp containers at a farm in Kebumen, Centra Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers sort shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Centra Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers sort shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Centra Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm worker Dias Yudho Prihantoro sits on his bed inside the hut where he and his brother stay during their work shifts at a shrimp farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Andika Yudha Agusta, right, and his brother Dias Yudho Prihantoro who work together at a shrimp farm sit inside the hut where they stay during their work shifts at the farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Yulius Cahyonugroho poses for a photo at his shrimp farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm worker Andika Yudha Agusta feed shrimps at a shrimp farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm worker Andika Yudha Agusta feed shrimps at a shrimp farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A worker throws a net as he harvests shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers harvest shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm workers Andika Yudha Agusta, right, and his brother Dias Yudho Prihantoro, left, harvest shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Farm workers Andika Yudha Agusta, left, and his brother Dias Yudho Prihantoro, right, harvest shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Central Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Workers pull a net as they harvest shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Centra Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

A worker sorts shrimps at a farm in Kebumen, Centra Java, Indonesia, Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)