SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Three years after the 30-year-old South Korean woman received a barrage of online fake images that depicted her nude, she is still being treated for trauma. She struggles to talk with men. Using a mobile phone brings back the nightmare.

“It completely trampled me, even though it wasn’t a direct physical attack on my body,” she said in a phone interview with The Associated Press. She didn't want her name revealed because of privacy concerns.

Many other South Korean women recently have come forward to share similar stories as South Korea grapples with a deluge of non-consensual, explicit deepfake videos and images that have become much more accessible and easier to create.

It was not until last week that parliament revised a law to make watching or possessing deepfake porn content illegal.

Most suspected perpetrators in South Korea are teenage boys. Observers say the boys target female friends, relatives and acquaintances — also mostly minors — as a prank, out of curiosity or misogyny. The attacks raise serious questions about school programs but also threaten to worsen an already troubled divide between men and women.

Deepfake porn in South Korea gained attention after unconfirmed lists of schools that had victims spread online in August. Many girls and women have hastily removed photos and videos from their Instagram, Facebook and other social media accounts. Thousands of young women have staged protests demanding stronger steps against deepfake porn. Politicians, academics and activists have held forums.

“Teenage (girls) must be feeling uneasy about whether their male classmates are okay. Their mutual trust has been completely shattered,” said Shin Kyung-ah, a sociology professor at South Korea’s Hallym University.

The school lists have not been formally verified, but officials including President Yoon Suk Yeol have confirmed a surge of explicit deepfake content on social media. Police have launched a seven-month crackdown.

Recent attention to the problem has coincided with France’s arrest in August of Pavel Durov, the founder of the messaging app Telegram, over allegations that his platform was used for illicit activities including the distribution of child sexual abuse. South Korea's telecommunications and broadcast watchdog said Monday that Telegram has pledged to enforce a zero-tolerance policy on illegal deepfake content.

Police say they’ve detained 387 people over alleged deepfake crimes this year, more than 80% of them teenagers. Separately, the Education Ministry says about 800 students have informed authorities about intimate deepfake content involving them this year.

Experts say the true scale of deepfake porn in the country is far bigger.

The U.S. cybersecurity firm Security Hero called South Korea “the country most targeted by deepfake pornography” last year. In a report, it said South Korean singers and actresses constitute more than half of the people featured in deepfake pornography worldwide.

The prevalence of deepfake porn in South Korea reflects various factors including heavy use of smart phones; an absence of comprehensive sex and human rights education in schools and inadequate social media regulations for minors as well as a “misogynic culture” and social norms that “sexually objectify women,” according to Hong Nam-hee, a research professor at the Institute for Urban Humanities at the University of Seoul.

Victims speak of intense suffering.

In parliament, lawmaker Kim Nam Hee read a letter by an unidentified victim who she said tried to kill herself because she didn't want to suffer any longer from the explicit deepfake videos someone had made of her. Addressing a forum, former opposition party leader Park Ji-hyun read a letter from another victim who said she fainted and was taken to an emergency room after receiving sexually abusive deepfake images and being told by her perpetrators that they were stalking her.

The 30-year-old woman interviewed by The AP said that her doctoral studies in the United States were disrupted for a year. She is receiving treatment after being diagnosed with panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in 2022.

Police said they've detained five men for allegedly producing and spreading fake explicit contents of about 20 women, including her. The victims are all graduates from Seoul National University, the country’s top school. Two of the men, including one who allegedly sent her fake nude images in 2021, attended the same university, but she said has no meaningful memory of them.

The woman said the images she received on Telegram used photos she had posted on the local messaging app Kakao Talk, combined with nude photos of strangers. There were also videos showing men masturbating and messages describing her as a promiscuous woman or prostitute. One photo shows a screen shot of a Telegram chatroom with 42 people where her fake images were posted.

The fake images were very crudely made but the woman felt deeply humiliated and shocked because dozens of people — some of whom she likely knows — were sexually harassing her with those photos.

Building trust with men is stressful, she said, because she worries that “normal-looking people could do such things behind my back.”

Using a smart phone sometimes revives memories of the fake images.

“These days, people spend more time on their mobile phones than talking face to face with others. So we can’t really easily escape the traumatic experience of digital crimes if those happen on our phones,” she said. “I was very sociable and really liked to meet new people, but my personality has totally changed since that incident. That made my life really difficult and I’m sad.”

Critics say authorities haven’t done enough to counter deepfake porn despite an epidemic of online sex crimes in recent years, such as spy cam videos of women in public toilets and other places. In 2020, members of a criminal ring were arrested and convicted of blackmailing dozens of women into filming sexually explicit videos for them to sell.

“The number of male juveniles consuming deepfake porn for fun has increased because authorities have overlooked the voices of women” demanding stronger punishment for digital sex crimes, the monitoring group ReSET said in comments sent to AP.

South Korea has no official records on the extent of deepfake online porn. But ReSET said a recent random search of an online chatroom found more than 4,000 sexually exploitive images, videos and other items.

Reviews of district court rulings showed less than a third of the 87 people indicted by prosecutors for deepfake crimes since 2021 were sent to prison. Nearly 60% avoided jail by receiving suspended terms, fines or not-guilty verdicts, according to lawmaker Kim's office. Judges tended to lighten sentences when those convicted repented for their crimes or were first time offenders.

The deepfake problem has gained urgency given South Korea's serious rifts over gender roles, workplace discrimination facing women, mandatory military service for men and social burdens on men and women.

Kim Chae-won, a 25-year-old office worker, said some of her male friends shunned her after she asked them what they thought about digital sex violence targeting women.

“I feel scared of living as a woman in South Korea,” said Kim Haeun, a 17-year-old high school student who recently removed all her photos on Instagram. She said she feels awkward when talking with male friends and tries to distance herself from boys she doesn't know well.

“Most sex crimes target women. And when they happen, I think we are often helpless," she said.

The National Assembly passes bills toughening the punishment for deepfake sex crimes in Seoul, South Korea, Thursday, Sept. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

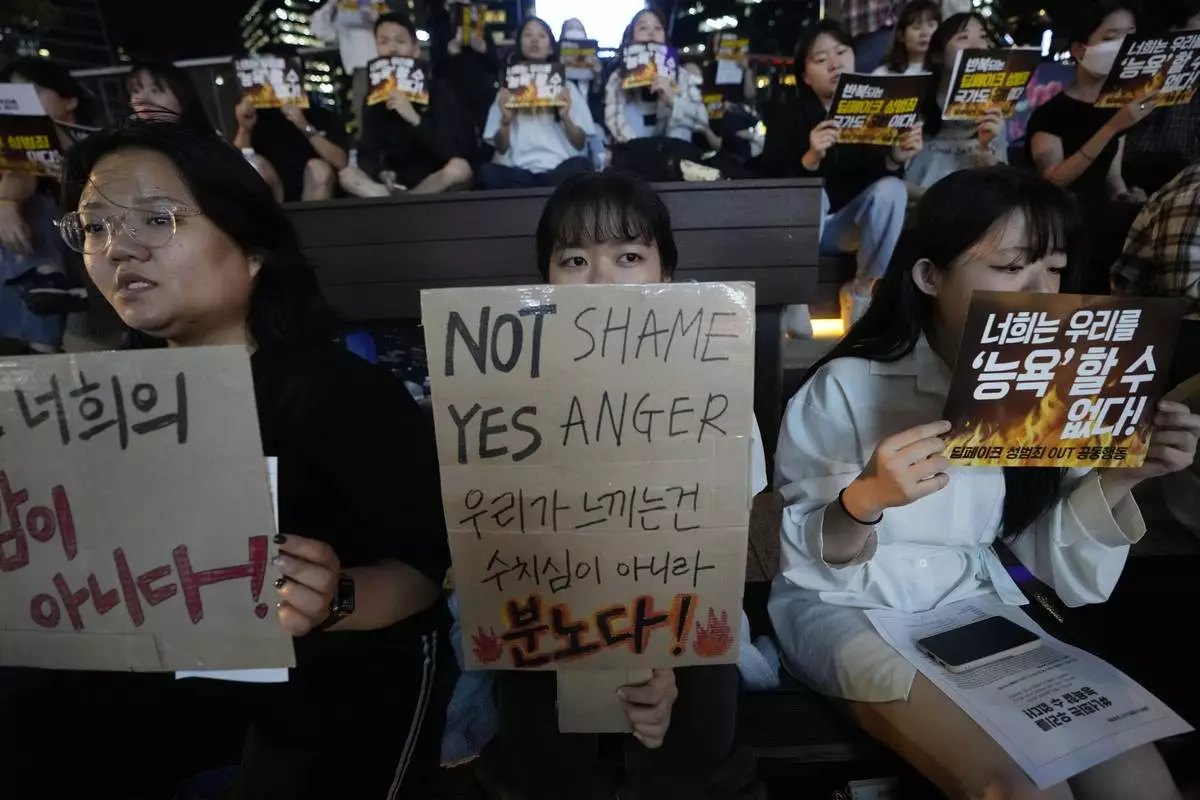

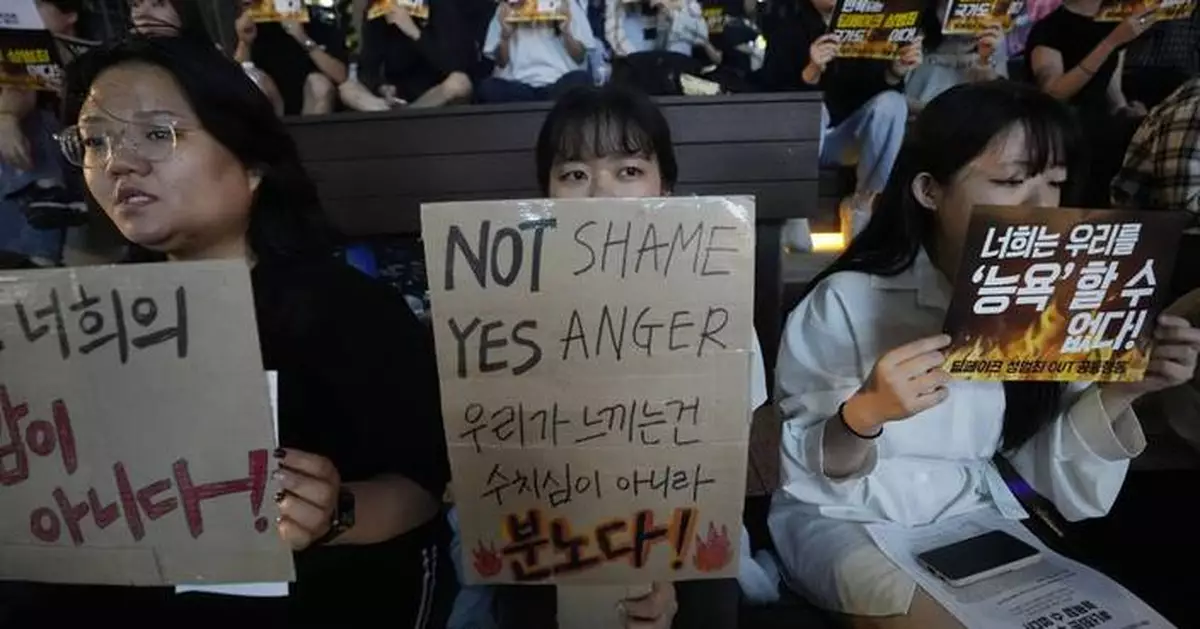

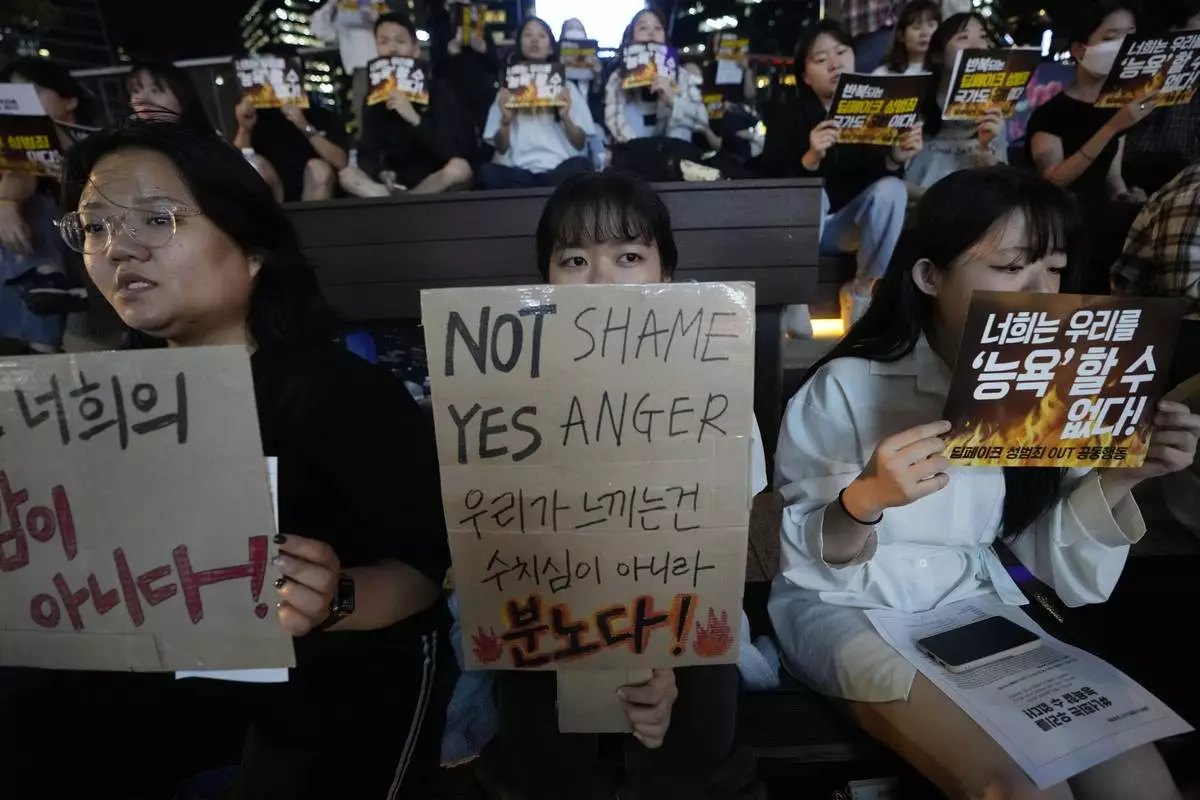

Citizens stage a rally against deepfake sex crime in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. The banners read "You can't insult us." (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

Citizens stage a rally against deepfake sex crime in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

HORSESHOE BEACH, Fla. (AP) — It was just a month ago that Brooke Hiers left the state-issued emergency trailer where her family had lived since Hurricane Idalia slammed into her Gulf Coast fishing village of Horseshoe Beach in August 2023.

Hiers and her husband Clint were still finishing the electrical work in the home they painstakingly rebuilt themselves, wiping out Clint’s savings to do so. They never will finish that wiring job.

Hurricane Helene blew their newly renovated home off its four foot-high pilings, sending it floating into the neighbor’s yard next door.

“You always think, ‘Oh, there’s no way it can happen again’,” Hiers said. “I don’t know if anybody’s ever experienced this in the history of hurricanes.”

For the third time in 13 months, this windswept stretch of Florida’s Big Bend took a direct hit from a hurricane — a one-two-three punch to a 50-mile (80-kilometer) sliver of the state’s more than 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometers) of coastline, first by Idalia, then Category 1 Hurricane Debby in August 2024 and now Helene.

Hiers, who sits on Horseshoe Beach’s town council, said words like “unbelievable” are beginning to lose their meaning.

“I’ve tried to use them all. Catastrophic. Devastating. Heartbreaking … none of that explains what happened here,” Hiers said.

The back-to-back hits to Florida’s Big Bend are forcing residents to reckon with the true costs of living in an area under siege by storms that researchers say are becoming stronger because of climate change.

The Hiers, like many others here, can’t afford homeowner’s insurance on their flood-prone houses, even if it was available. Residents who have watched their life savings get washed away multiple times are left with few choices — leave the communities where their families have lived for generations, pay tens of thousands of dollars to rebuild their houses on stilts as building codes require, or move into a recreational vehicle they can drive out of harm’s way.

That’s if they can afford any of those things. The storm left many residents bunking with family or friends, sleeping in their cars, or sheltering in what’s left of their collapsing homes.

Janalea England wasn't waiting for outside organizations to get aid to her friends and neighbors, turning her commercial fish market in the river town of Steinhatchee into a pop-up donation distribution center, just like she did after Hurricane Idalia. A row of folding tables was stacked with water, canned food, diapers, soap, clothes and shoes, a steady stream of residents coming and going.

“I’ve never seen so many people homeless as what I have right now. Not in my community,” England said. “They have nowhere to go.”

The sparsely populated Big Bend is known for its towering pine forests and pristine salt marshes that disappear into the horizon, a remote stretch of largely undeveloped coastline that’s mostly dodged the crush of condos, golf courses and souvenir strip malls that has carved up so much of the Sunshine State.

This is a place where teachers, mill workers and housekeepers could still afford to live within walking distance of the Gulf’s white sand beaches. Or at least they used to, until a third successive hurricane blew their homes apart.

Helene was so destructive, many residents don’t have a home left to clean up, escaping the storm with little more than the clothes on their backs, even losing their shoes to the surging tides.

“People didn’t even have a Christmas ornament to pick up or a plate from their kitchen,” Hiers said. “It was just gone.”

In a place where people are trying to get away from what they see as government interference, England, who organized her own donation site, isn’t putting her faith in government agencies and insurance companies.

“FEMA didn’t do much,” she said. “They lost everything with Idalia and they were told, ‘here, you can have a loan.’ I mean, where’s our tax money going then?”

England’s sister, Lorraine Davis, got a letter in the mail just days before Helene hit declaring that her insurance company was dropping her, with no explanation other than her home “fails to meet underwriting”.

Living on a fixed income, Davis has no idea how she’ll repair the long cracks that opened up in the ceiling of her trailer after the last storm.

“We'll all be on our own,” England said. “We're used to it.”

In the surreal aftermath of this third hurricane, some residents don’t have the strength to clean up their homes again, not with other storms still brewing in the Gulf.

With marinas washed away, restaurants collapsed and vacation homes blown apart, many commercial fishermen, servers and housecleaners lost their homes and their jobs on the same day.

Those who worked at the local sawmill and paper mill, two bedrock employers in the area, were laid off in the past year too. Now a convoy of semi-trucks full of hurricane relief supplies have set up camp at the shuttered mill in the city of Perry.

Hud Lilliott was a mill worker for 28 years, before losing his job and now his canal-front home in Dekle Beach, just down the street from the house where he grew up.

Lilliott and his wife Laurie hope to rebuild their house there, but they don’t know how they’ll pay for it. And they’re worried the school in Steinhatchee where Laurie teaches first grade could become another casualty of the storm, as the county watches its tax base float away.

“We've worked our whole lives and we're so close to where they say the ‘golden years’," Laurie said. "It's like you can see the light and it all goes dark.”

Dave Beamer rebuilt his home in Steinhatchee after it was “totaled” by Hurricane Idalia, only to see it washed into the marsh a year later.

“I don’t think I can do that again,” Beamer said. “Everybody’s changing their mind about how we’re going to live here.”

A waterlogged clock in a shed nearby shows the moment when time stopped, marking before Helene and after.

Beamer plans to stay in this river town, but put his home on wheels — buying a camper and building a pole barn to park it under.

In Horseshoe Beach, Hiers is waiting for a makeshift town hall to be delivered in the coming days, a double-wide trailer where they’ll offer what services they can for as long as they can. She and her husband are staying with their daughter, a 45-minute drive away.

“You feel like this could be the end of things as you knew it. Of your town. Of your community,” Hiers said. “We just don't even know how to recover at this point.”

Hiers said she and her husband will probably buy an RV and park it where their home once stood. But they won't be moving back to Horseshoe Beach for good until this year's storms are done.

They can't bear to do this again.

Kate Payne is a corps member for The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

Associated Press coverage of philanthropy and nonprofits receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content. For all of AP’s philanthropy coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/philanthropy

Maddie Kelley shows the high-water line left behind by Hurricane Helene on a seashell windchime at her family's home in Steinhatchee, Fla., Saturday, Sept. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

The sun sets over the storm-damaged Steinhatchee marina near where the Steinhatchee River flows into the Gulf of Mexico, Sunday, Sept. 29, 2024, in the aftermath of Hurricane Helen. (AP Photo/Kate Payne) Kate Payne Reporter, State Government Education Tallahassee, FL C 850.545.4283 kpayne@ap.or

The sun sets over a flooded road and a collapsed building in Steinhatchee, Fla., Sunday, Sept. 29, 2024, in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. (AP Photo/Kate Payne

Dave Beamer walks past the partially destroyed trailer he's been living in, Sunday, Sept. 29, 2024, in Steinhatchee, Fla., after Hurricane Helene washed his home into a marsh. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

Dave Beamer surveys debris left behind by Hurricane Helene along his street in Steinhatchee, Fla., Sunday. Sept. 29, 2024. Beamer had just rebuilt his home in the wake of Hurricane Idalia in August 2023, before Helene washed it into a marsh. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

Brooke Hiers surveys the damage done to her home, Monday, Sept. 30, 2024, in Horseshoe Beach, Fla., in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. Hiers and her husband rebuilt the home in the wake of Hurricane Idalia, which washed ashore in August, 2023, only to see it destroyed by another storm 13 months later. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

Brooke Hiers stands in front of where her home used to sit in Horseshoe Beach, Fla., Monday, Sept. 30, 2024, in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. She and her husband had just rebuilt the home after Hurricane Idalia hit in August, 2023, before Hurricane Helene blew the house off its pilings and floated it into the neighbor's yard next door. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

A waterlogged clock hangs a shed, Sunday, Sept 29, 2024, in Steinhatchee, Fla., in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

Leslie and J.D. High hold photos they found in the debris that Hurricane Helene left near their home in Dekle Beach in rural Taylor County, Fla., Friday, Sept. 27, 2024. Among the photos was a polaroid showing damage from a storm known as the "Storm of the Century" that hit the area in March, 1993. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)

Laurie Lilliott stands amid the wreckage of her destroyed home in Dekle Beach in rural Taylor County, Fla., Friday, Sept. 27, 2024, in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. (AP Photo/Kate Payne)