LOS ANGELES (AP) — Prosecutors in Los Angeles are reviewing new evidence in the case of Erik and Lyle Menendez to determine whether they should be serving life sentences for killing their parents in their Beverly Hills mansion more than 35 years ago, the city's district attorney said Thursday.

Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón said during a news conference that there is no question Erik Menendez, 53, and his 56-year-old brother, Lyle Menendez, committed the murders, but his office will be reviewing new evidence and will make a decision on whether a resentencing is warranted in the notorious case that captured national attention.

Click to Gallery

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Prosecutors in Los Angeles are reviewing new evidence in the case of Erik and Lyle Menendez to determine whether they should be serving life sentences for killing their parents in their Beverly Hills mansion more than 35 years ago, the city's district attorney said Thursday.

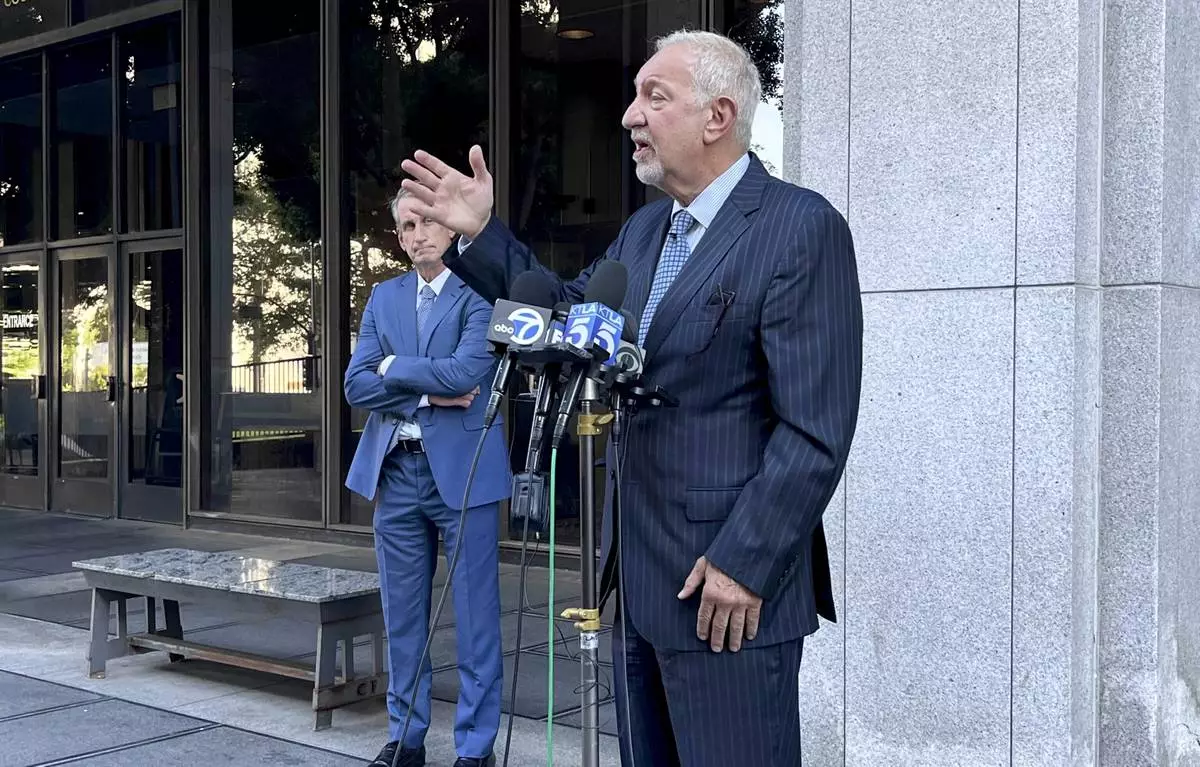

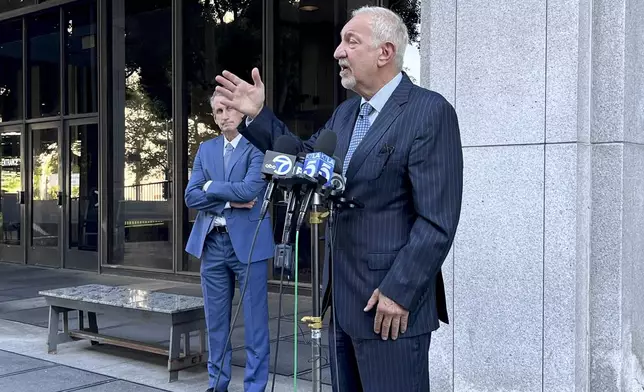

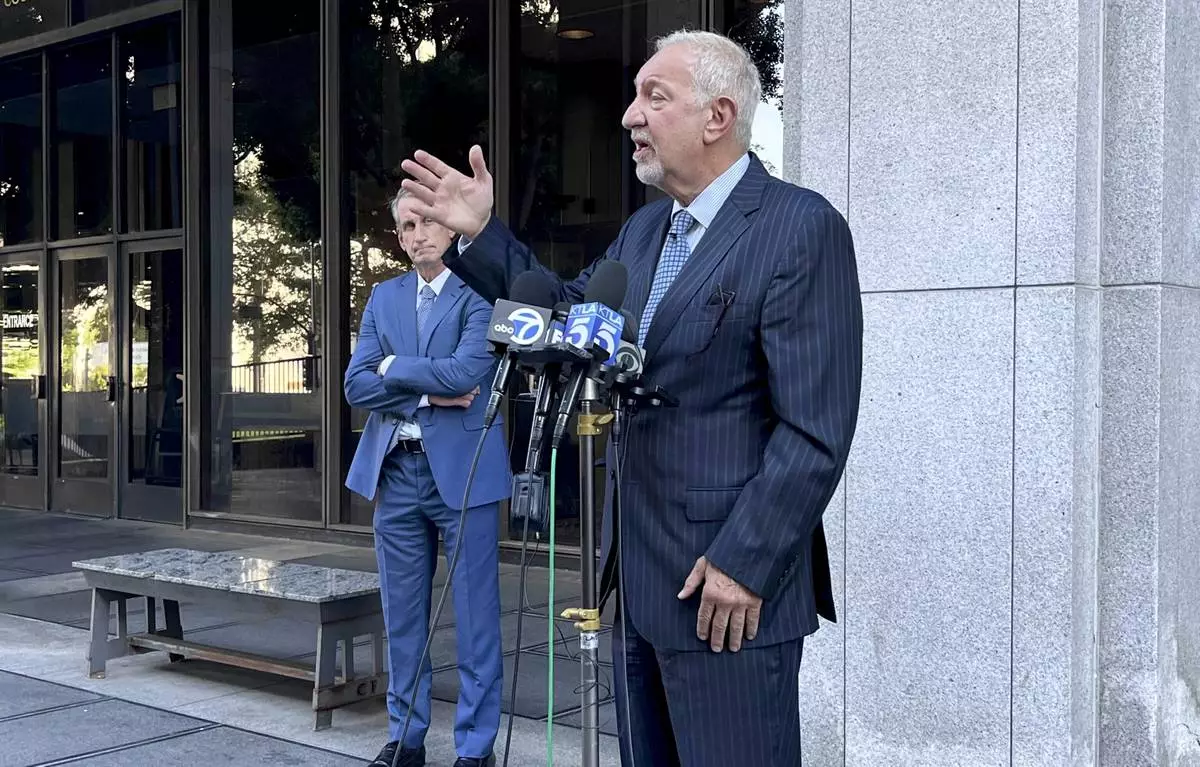

Attorney Mark Geragos informs the media on developments on the case of brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez, both serving life sentences for the murder of their parents in 1989, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jaimie Ding)

Attorneys Bryan Freedman, center, and Mark Geragos, left, address the media on developments on the case of brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez, both serving life sentences for the murder of their parents in 1989, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jaimie Ding)

FILE - Lyle Menendez looks up during testimony in his and brother Erik's retrial for the shotgun slayings of their parents, Oct. 20, 1995 in Los Angeles. (Steve Grayson/Pool Photo via AP, File)

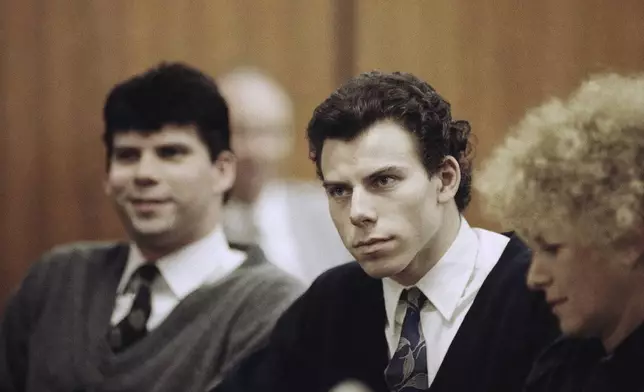

FILE - Erik Menendez, center, listens to his attorney Leslie Abramson, as his brother Lyle looks on in a Beverly Hills, California, May 17, 1991. (AP Photo/Julie Markes, File)

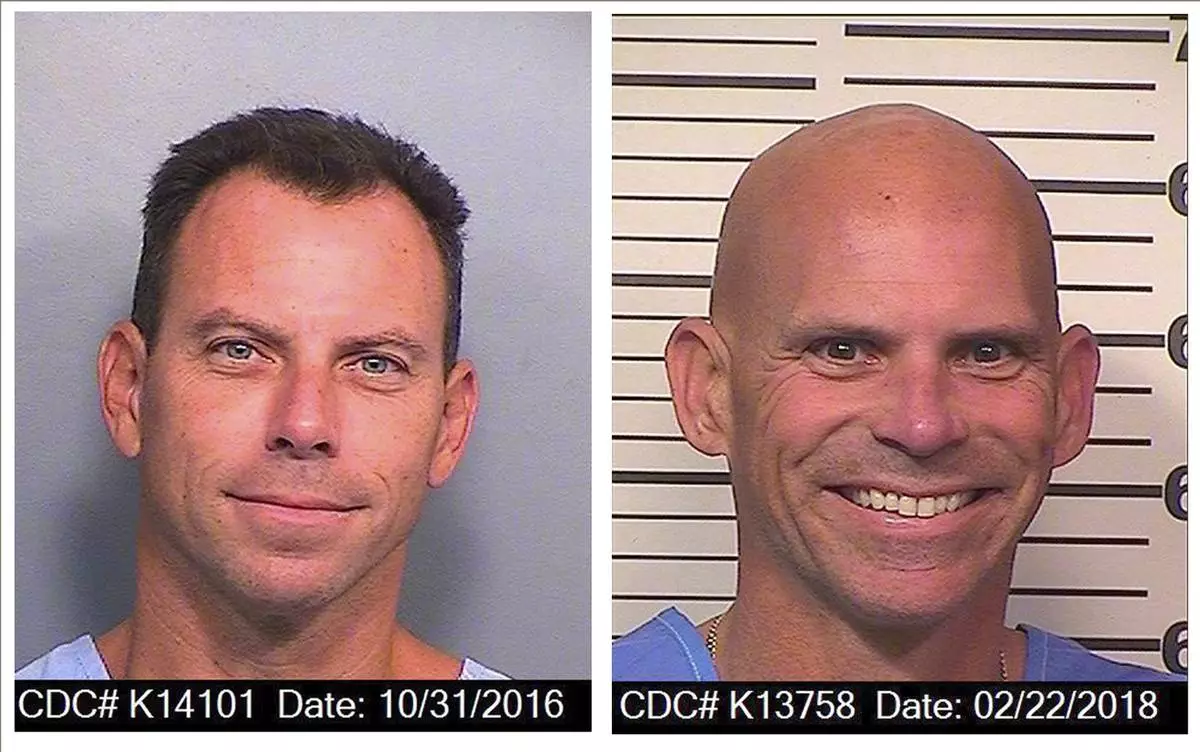

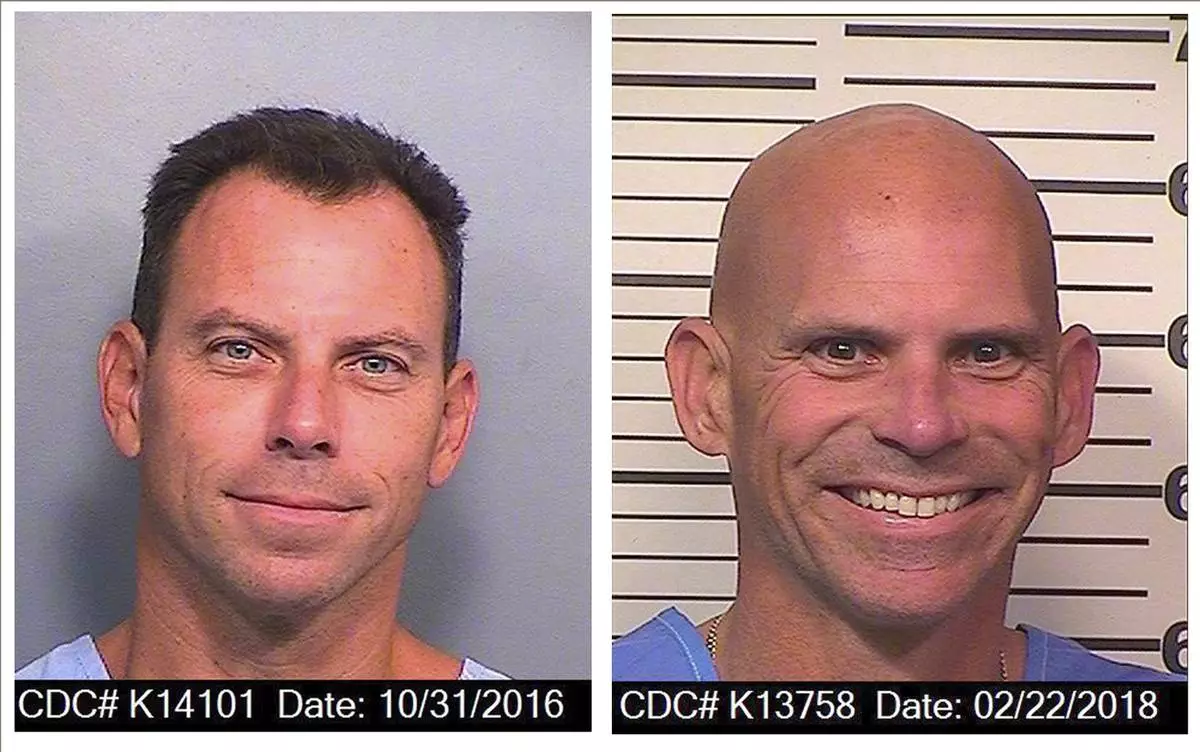

FILE - An Oct. 31, 2016, photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows Erik Menendez, left, and a Feb. 22, 2018 photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows Lyle Menendez. (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation via AP, File )

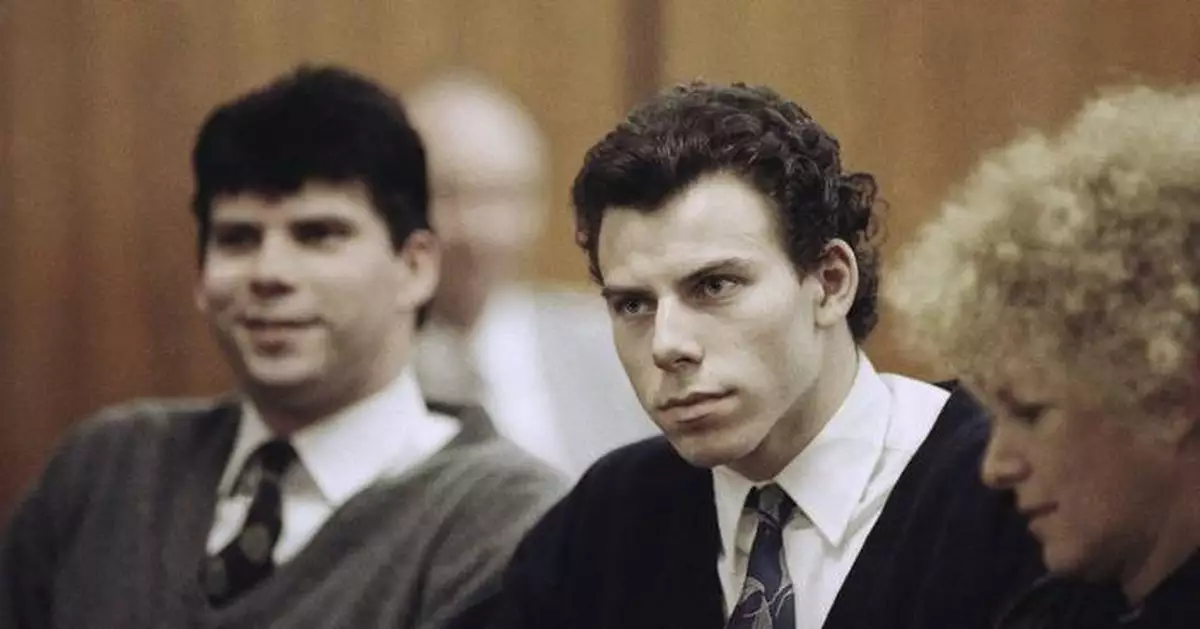

FILE - Lyle, left, and Erik Menendez sit with defense attorney Leslie Abramson, right, in Beverly Hills Municipal Court during a hearing, Nov. 26, 1990. (AP Photo/Nick Ut, File)

The new evidence presented in a petition includes a letter written by Erik Menendez that his attorneys say corroborates the allegations that he was sexually abused by his father.

The brothers have said they killed their parents out of self-defense after enduring a lifetime of physical, emotional and sexual abuse from them. Their attorneys argue that because of society's changing views on sexual abuse, that the brothers may not have been convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole today.

Bryan Freedman, the extended family’s lawyers, said they strongly support the brothers’ release.

“She wishes nothing more than for them to be released,” Freedman said of Joan VanderMolen, the brothers’ aunt.

The brothers’ attorneys said the family believed from the beginning they should have been charged with manslaughter rather than murder. Manslaughter was not an option for the jury during the second trial that ultimately led to the brothers’ murder conviction, attorney Mark Geragos said.

Lyle Menendez, who was then 21, and Erik Menendez, then 18, admitted they fatally shot-gunned their entertainment executive father Jose Menendez and their mother, Kitty Menendez, in 1989 but said they feared their parents were about to kill them to prevent the disclosure of the father’s long-term sexual molestation of Erik.

Prosecutors at the time contended there was no evidence of any molestation. They said the sons were after their parents’ multimillion-dollar estate.

Jurors rejected a death sentence in favor of life without parole.

Attorney Cliff Gardner, who also represents the brothers, said they are pleased by the district attorney’s decision. The attorneys have asked for the court to vacate their conviction.

“Given today’s very different understanding of how sexual and physical abuse impacts children — both boys and girls — and the remarkable new evidence, we think resentencing is the appropriate result,” Gardner said in an email Thursday to The Associated Press. “The brothers have served more than 30 years in prison. That is enough.”

The case has gained new attention in recent weeks after Netflix began streaming the true-crime drama “ Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story. ”

In a statement on X posted by his wife, Erik Menendez called the show a “dishonest portrayal” of what happened that has taken them back to a time when prosecutors “built a narrative on a belief system that males were not sexually abused, and that males experience rape trauma differently from women.”

Gascón said he believes that the topic of sexual assault would have been treated with more sensitivity if the case had happened today.

“We have not decided on an outcome. We are reviewing information,” Gascón said.

He said his office did not know the “validity” of what was presented at the trial.

Gascón, who is seeking reelection, noted that more than 300 people have been resentenced during his term, and only four have gone on to commit a crime again.

A hearing was scheduled for Nov. 29.

Lyle Menendez recently earned a sociology degree from the University of California, Irvine, through a prison program. Geragos said they have been model prisoners despite believing they would never be released.

“I think it's time,” Geragos said. “The family thinks it's time.”

Reality TV star and celebrity personality Kim Kardashian, who has advocated for criminal justice reform, also weighed in, writing in a personal essay shared with NBC News that the outsized media attention on the first trial that was nationally televised denied them justice.

She noted with “their suffering and stories of abuse ridiculed in skits on ‘Saturday Night Live’” that they were painted as “two arrogant, rich kids from Beverly Hills who killed their parents out of greed. There was no room for empathy, let alone sympathy.”

“Erik and Lyle had no chance of a fair trial against this backdrop," Kardashian wrote.

This story has been updated to correct the name of the Netflix true-crime drama on the Menendez brothers to “Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story," not “The Menendez Brothers.”

Attorney Mark Geragos informs the media on developments on the case of brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez, both serving life sentences for the murder of their parents in 1989, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jaimie Ding)

Attorney Mark Geragos informs the media on developments on the case of brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez, both serving life sentences for the murder of their parents in 1989, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jaimie Ding)

Attorneys Bryan Freedman, center, and Mark Geragos, left, address the media on developments on the case of brothers Lyle and Erik Menendez, both serving life sentences for the murder of their parents in 1989, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Jaimie Ding)

FILE - Lyle Menendez looks up during testimony in his and brother Erik's retrial for the shotgun slayings of their parents, Oct. 20, 1995 in Los Angeles. (Steve Grayson/Pool Photo via AP, File)

FILE - Erik Menendez, center, listens to his attorney Leslie Abramson, as his brother Lyle looks on in a Beverly Hills, California, May 17, 1991. (AP Photo/Julie Markes, File)

FILE - An Oct. 31, 2016, photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows Erik Menendez, left, and a Feb. 22, 2018 photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows Lyle Menendez. (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation via AP, File )

FILE - Lyle, left, and Erik Menendez sit with defense attorney Leslie Abramson, right, in Beverly Hills Municipal Court during a hearing, Nov. 26, 1990. (AP Photo/Nick Ut, File)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — They began a pilgrimage that thousands before them have done. They boarded long flights to their motherland, South Korea, to undertake an emotional, often frustrating, sometimes devastating search for their birth families.

These adoptees are among the 200,000 sent from South Korea to Western nations as children. Many have grown up, searched for their origin story and discovered that their adoption paperwork was inaccurate or fabricated. They have only breadcrumbs to go on: grainy baby photos, names of orphanages and adoption agencies, the towns where they were said to have been abandoned. They don’t speak the language. They’re unfamiliar with the culture. Some never learn their truth.

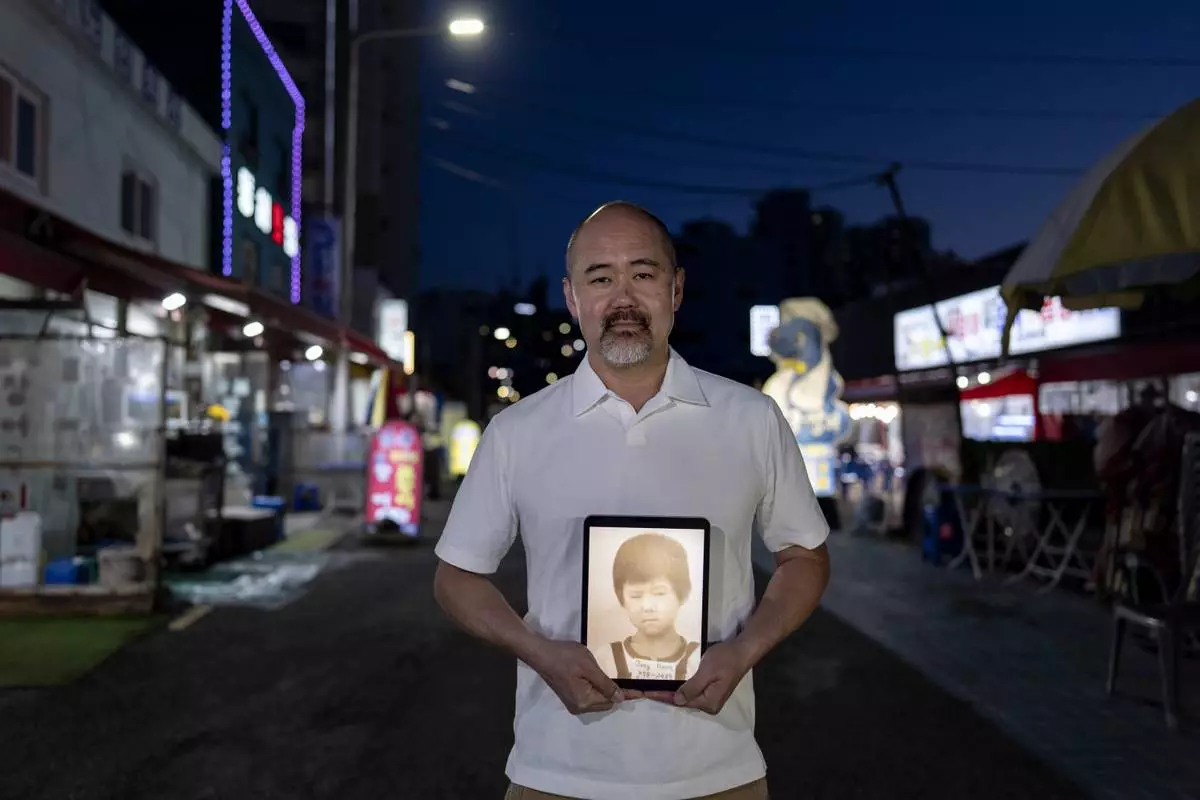

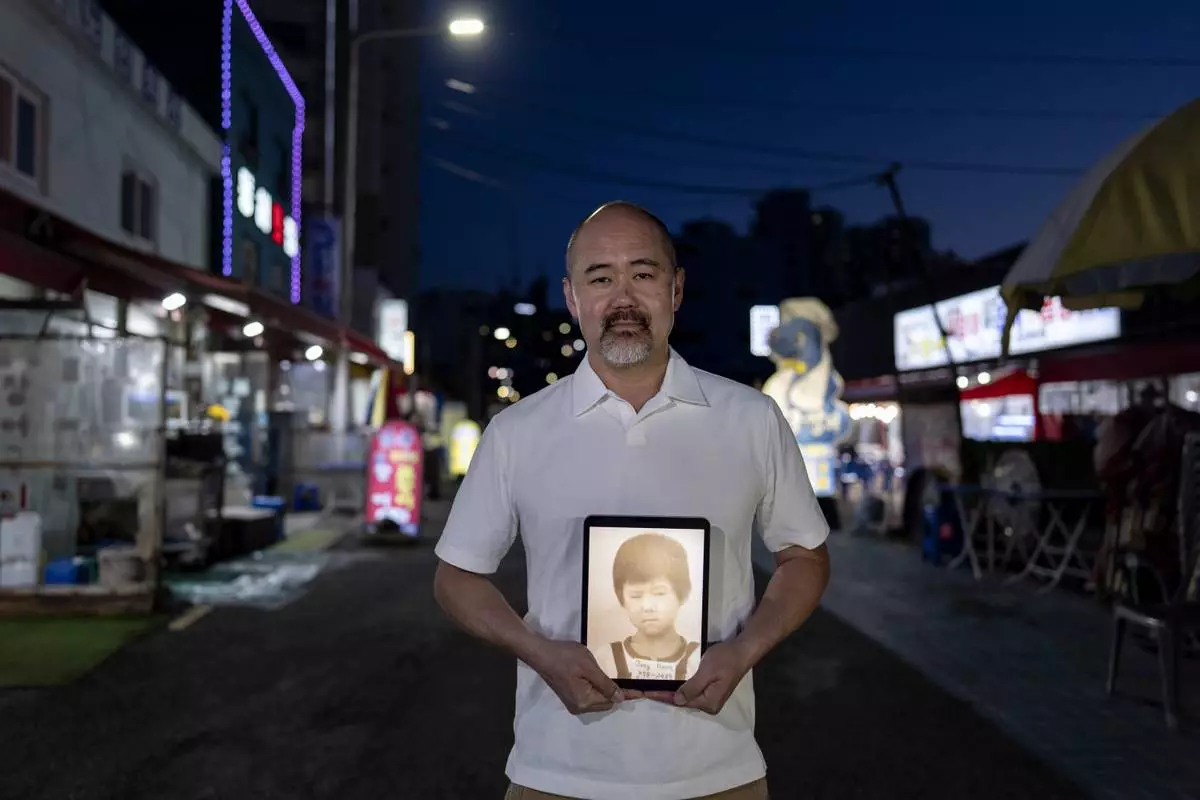

“I want my mother to know I’m OK and that her sacrifice was not in vain,” says Kenneth Barthel, adopted in 1979 at 6 years old to Hawaii.

He hung flyers all over Busan, where his mother abandoned him at a restaurant. She ordered him soup, went to the bathroom and never returned. Police found him wandering the streets and took him to an orphanage. He didn’t think much about finding his birth family until he had his own son, imagined himself as a boy and yearned to understand where he came from.

He has visited South Korea four times, without any luck. He says he’ll keep coming back, and tears rolled down his cheeks.

Some who make this trip learn things about themselves they’d thought were lost forever.

In a small office at the Stars of the Sea orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Maja Andersen sat holding Sister Christina Ahn’s hands. Her eyes grew moist as the sister translated the few details available about her early life at the orphanage.

She had loved being hugged, the orphanage documents said, and had sparkling eyes.

“Thank you so much, thank you so much,” Andersen repeated in a trembling voice. There was comfort in that — she had been hugged, she had smiled.

She’d come here searching for her family.

“I just want to tell them I had a good life and I’m doing well,” Andersen said to Sister Ahn.

Andersen had been admitted to the facility as a malnourished baby and was adopted at 7 months old to a family in Denmark, according to the documents. She says she’s grateful for the love her adoptive family gave her, but has developed an unshakable need to know where she came from. She visited this orphanage, city hall and a police station, but found no new clues about her birth family.

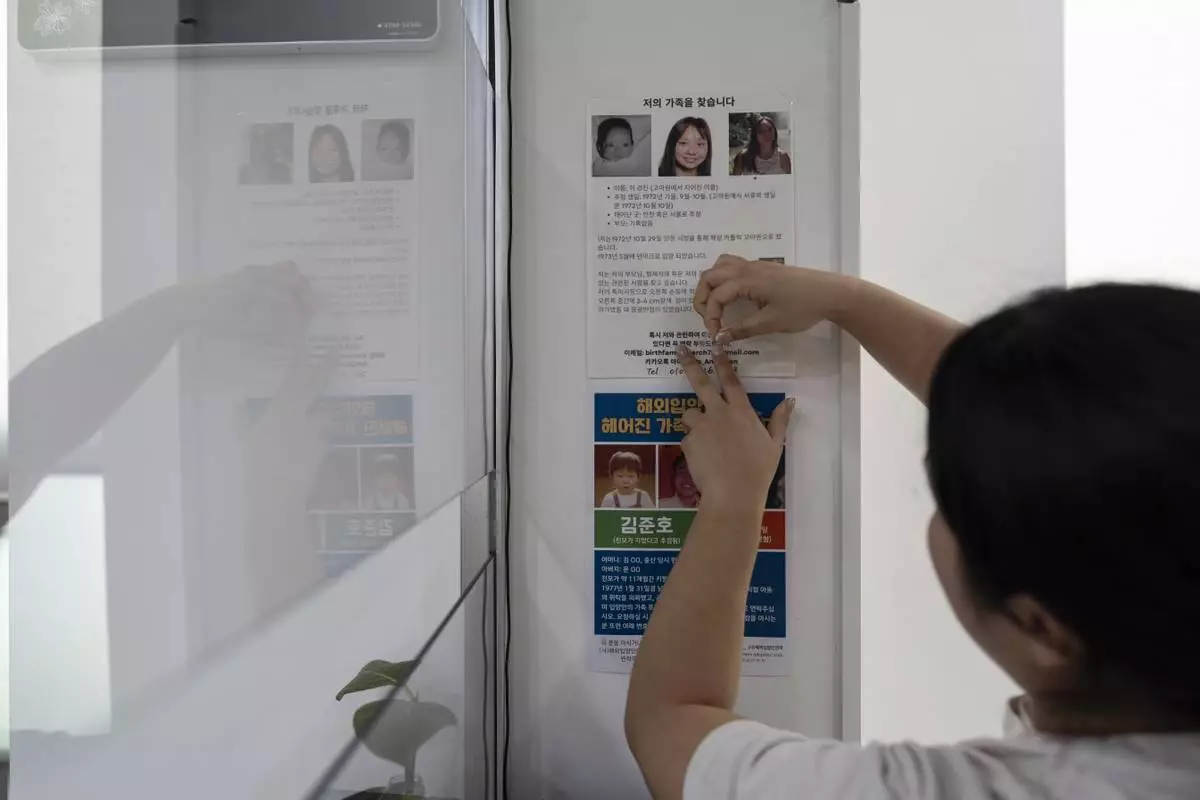

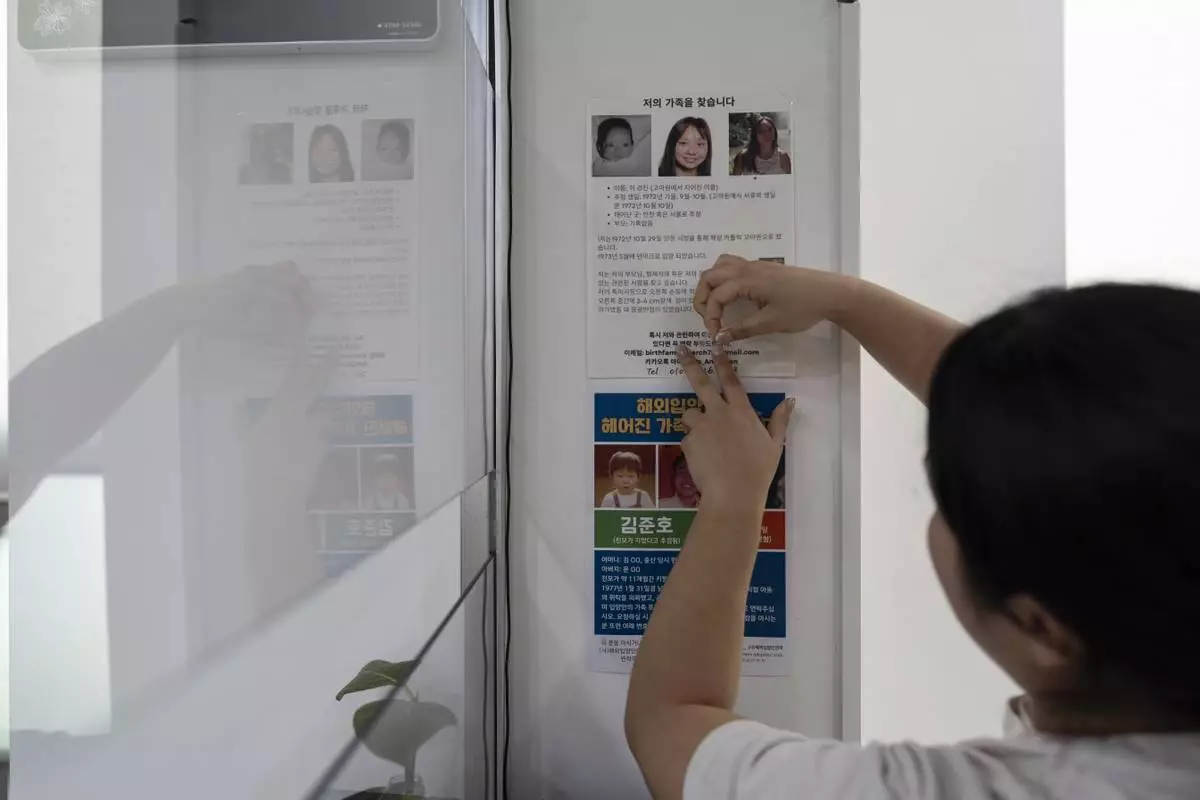

Still she remains hopeful, and plans to return to South Korea to keep trying. She posted a flyer on the wall of a police station not far from the orphanage, just above another left by an adoptee also searching for his roots.

Korean adoptees have organized, and now they help those coming along behind them. Non-profit groups conduct DNA testing. Sympathetic residents, police officers and city workers of the towns where they once lived often try to assist them. Sometimes adoption agencies are able to track down birth families.

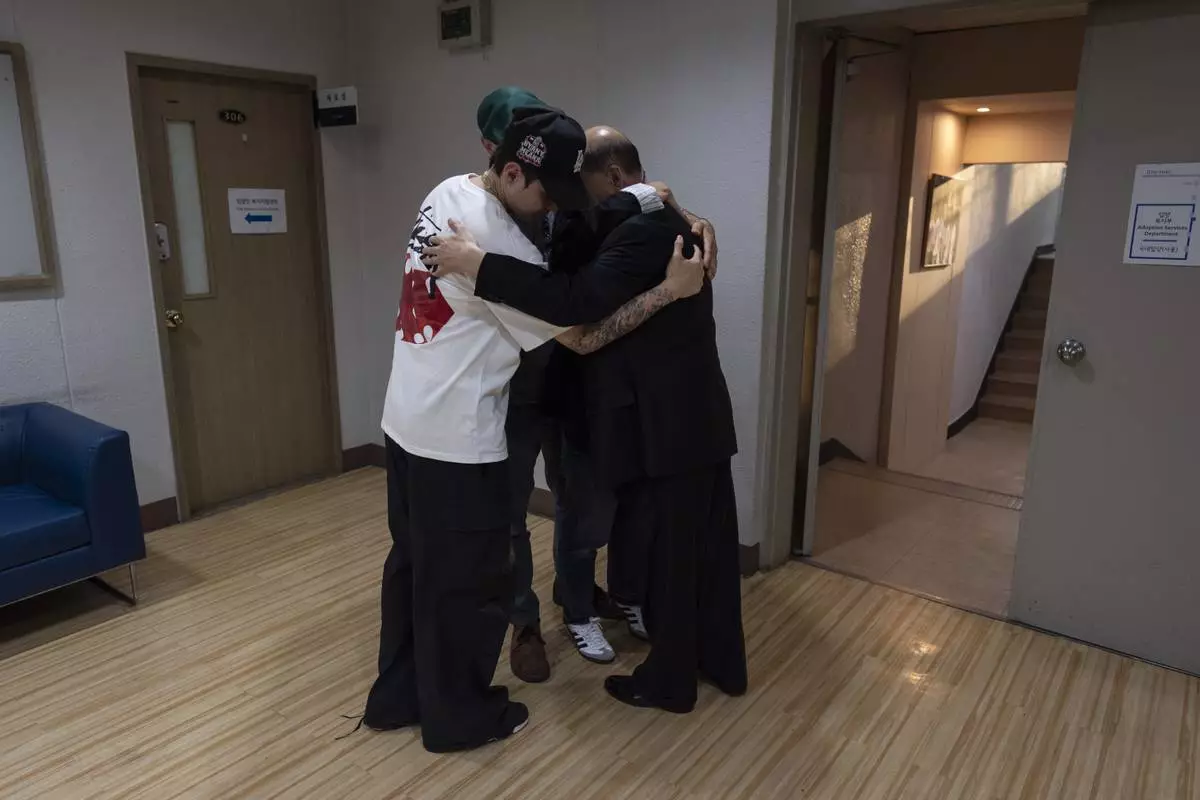

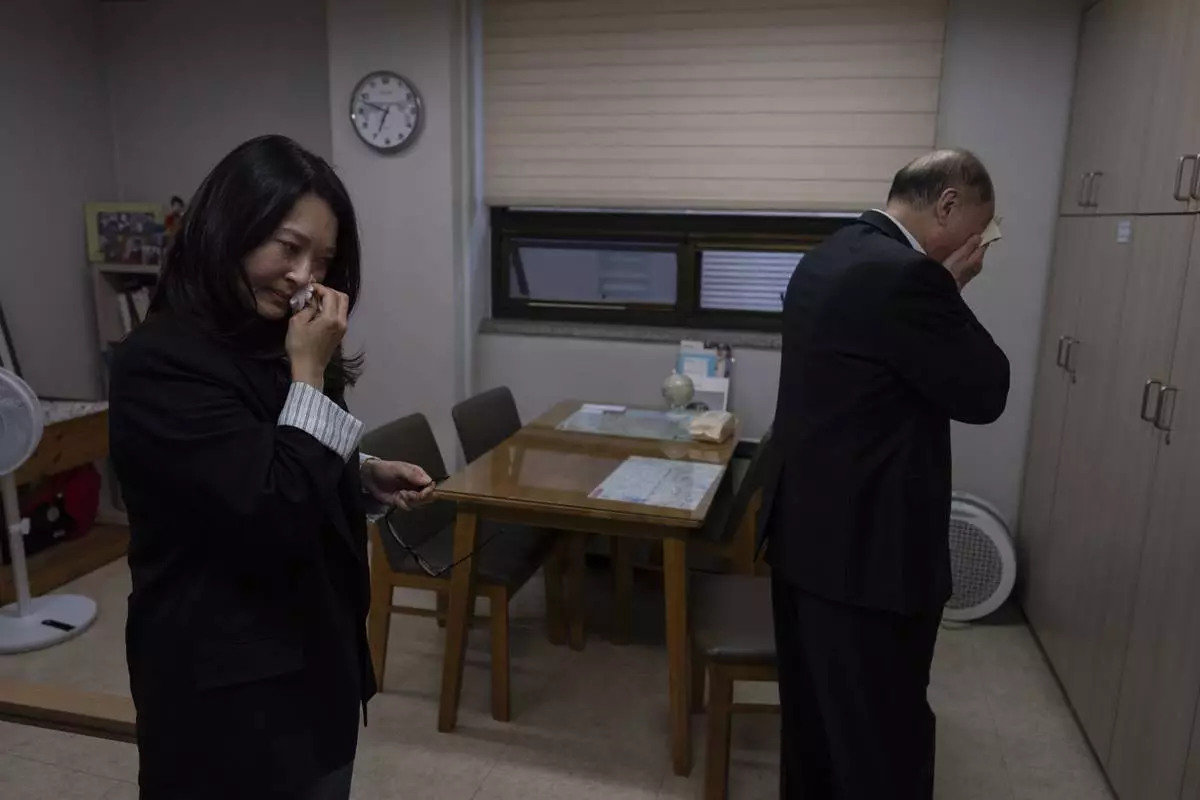

Nearly four decades after her adoption to the U.S., Nicole Motta in May sat across the table from a 70-year-old man her adoption agency had identified as her birth father. She typed “thanks for meeting me today” into a translation program on her phone to show him. A social worker placed hair samples into plastic bags for DNA testing.

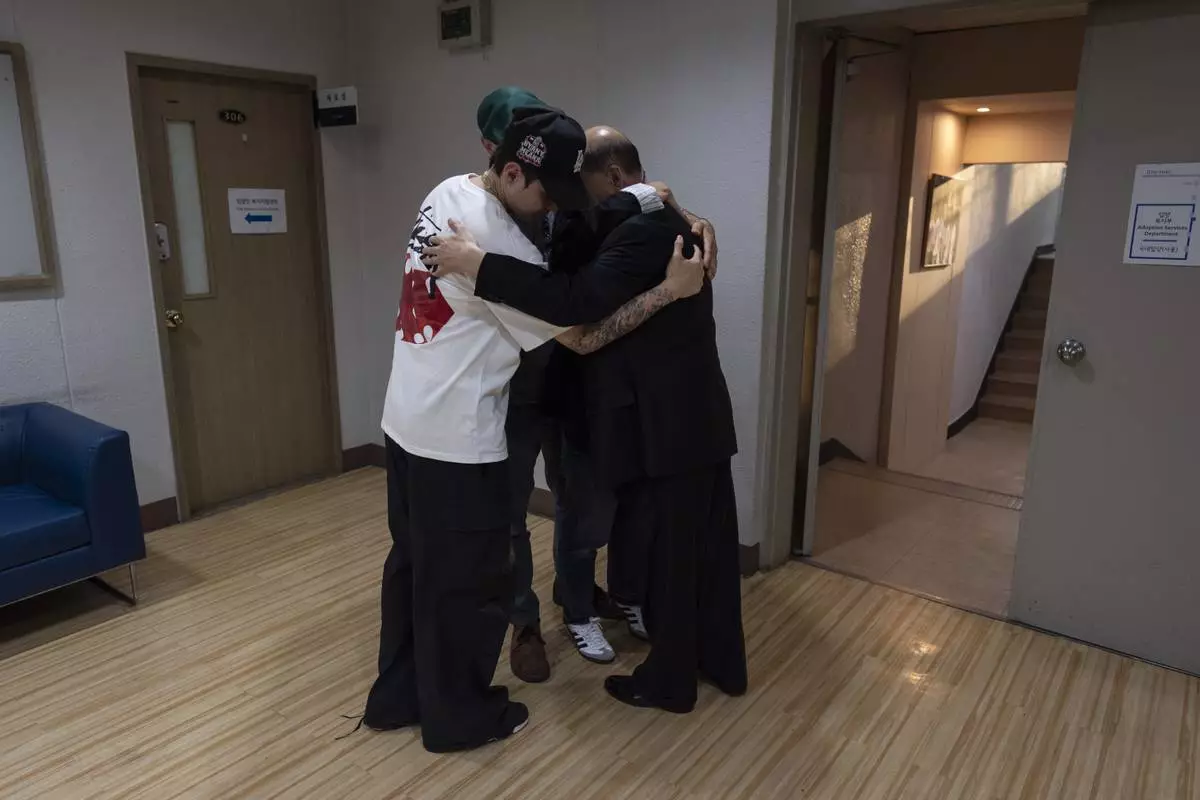

But the moment they hugged, Motta, adopted to the United States in 1985, didn’t need the results — she knew she’d come from this man.

“I am a sinner for not finding you,” he said.

Motta’s adoption documents say her father was away for work for long stretches and his wife struggled to raise three children alone. He told her she was gone when he came back from one trip, and claimed his brother gave her away. He hasn’t spoken to the brother since, he said, and never knew she was adopted abroad.

Motta’s adoption file leaves it unclear whether the brother had a role in her adoption. It says she was under the care of unspecified neighbors before being sent to an orphanage that referred her to an adoption agency, which sent her abroad in 1985.

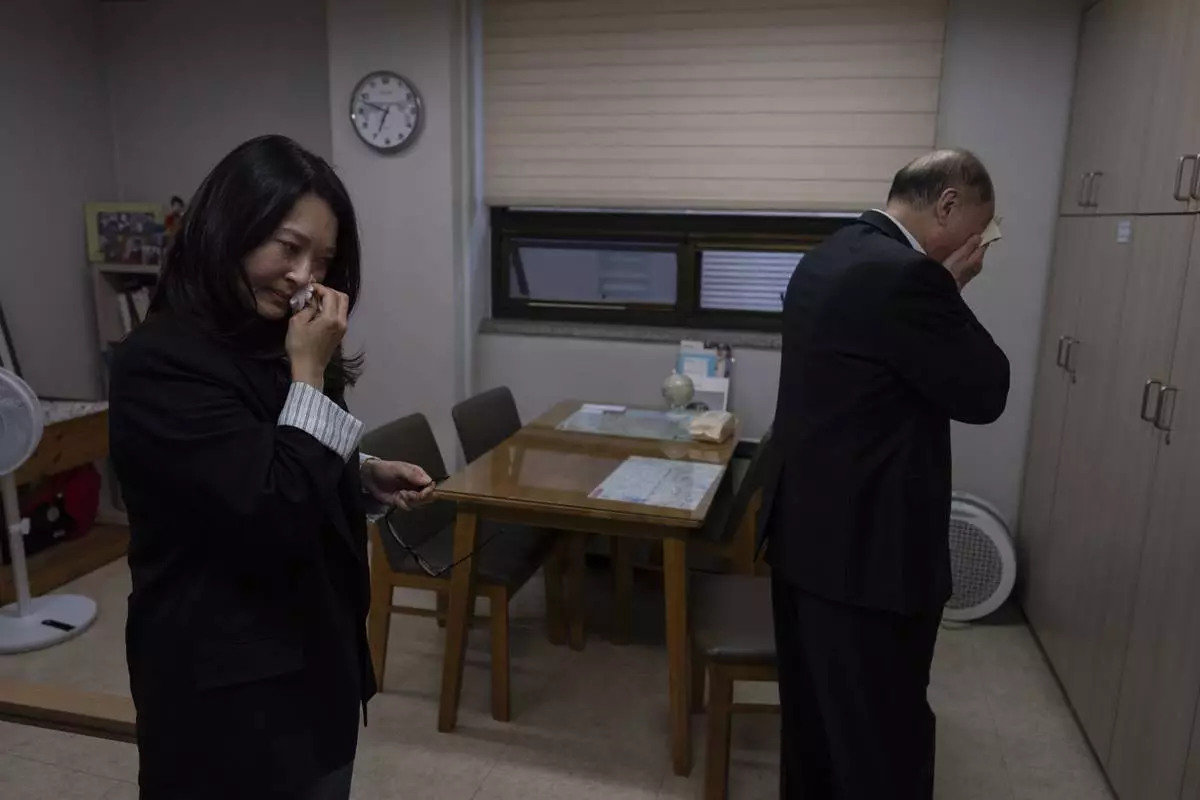

She studied his face. She wondered if she looks like her siblings or her mother, who has since died.

“I think I have your nose,” Motta said softly.

They both sobbed.

This story is part of an ongoing investigation led by The Associated Press in collaboration with FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes an interactive and documentary, South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning. Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org.

Jang Dae-chang hugs his daughter, Nicole Motta, and her family at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul on Friday, May 31, 2024, following their emotional first meeting. Motta, whose Korean name is Jang Hyeon-jung, was adopted by a family in Alabama, United States, in 1985. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Adoptee Nicole Motta, left, and her birth father, Jang Dae-chang, wipe tears after an emotional reunion at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, Friday, May 31, 2024. The moment they hugged, Motta, adopted to the United States in 1985, didn't need DNA test results, she knew she'd come from this man. "I am a sinner for not finding you," he said. "I think I have your nose," Motta said softly. They both sobbed. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, an adoptee visiting South Korea to look for her birth family, types "thank you for meeting me today," on her smartphone to translate it into Korean, as she meets her birth father for the first time at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, Friday, May 31, 2024. Motta's adoption documents say her father was away for work for long stretches and his wife struggled to raise three children alone. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta's son, Adler, collects hair samples from his mother for a DNA test as her birth father, Jang Dae-chang, reviews the paperwork at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, May 31, 2024. The two were reunited for the first time since she was adopted by a family in Alabama, United States, in 1985. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, left, turns to see her birth father, Jang Dae-chang, as he enters the room at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, May 31, 2024, as they're reunited for the first time since she was adopted in 1985 by a family in Alabama. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles to search for her birth family, visits Bucheon, South Korea, where she was born, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Many adoptees have grown up and are searching for their origin story. They have few details to go on. They don't speak the language. They're unfamiliar with the culture. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, second from left, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles, chats with Paek Kyeong-mi from Global Overseas Adoptees' Link, during a break from searching for Motta's birth family in Bucheon, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Holding a flyer asking for help to find adoptee Nicole Motta's birth family, long-time resident An Bok-rye knocks on the door of an apartment building where Motta's home once stood in Bucheon, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Sympathetic residents, police officers and city workers of the towns where they once lived often try to assist adoptees searching for their origin story. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, left, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles to search for her birth family, visits the neighborhood where she was born in Bucheon, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Her son, Adler, second from left, walks alongside long-time resident An Bok-rye who is helping with her search. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles, holds a tablet displaying a childhood picture, while traveling to search for her birth family in Yongin, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Motta, whose Korean name is Jang Hyeon-jung, visited the site that used to be the orphanage where she stayed until her adoption. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The flag of South Korea is displayed at the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. Korean adoptees have organized, and now they help those coming along behind them searching for their origin story. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

A city employee posts a flyer with photos of adoptee Maja Andersen from various ages in life and details about her birth search on the wall of a police station in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, above another left by an adoptee also searching for his roots. Andersen was adopted to a family in Denmark when she was an infant. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, hugs Sister Christina Ahn at Star of the Sea orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, while visiting the facility to look for details of her adoption. She had loved being hugged, the orphanage documents said, and had sparkling eyes. "Thank you so much, thank you so much," Andersen repeated in a trembling voice. There was comfort in that, she had been hugged, she had smiled. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, visits the Star of the Sea Orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, where she stayed until her adoption at seven months old. She visited the facility to look for documents in hopes of finding her family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, top, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, holds the hands of Sister Christina Ahn at Star of the Sea orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, during her visit to look for documents in hopes of finding her family. She stayed at the facility until her adoption at seven months old. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, right, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, and her daughter, Yasmin, attend the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Photos of adoptees participating at the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering are displayed on a large screen during the conference in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, front row third from left, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, holds a South Korean flag with others while taking a group photo at the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. These adoptees are among the 200,000 sent away from Korea to Western nations as children. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen sits for a photo in her hotel room, holding a tablet displaying her baby photo taken before her adoption to Denmark, as she visits Seoul, South Korea to search for her birth family, Monday, May 20, 2024. Andersen is among thousands of Korean adoptees who have taken a pilgrimage to their motherland for an emotional, often frustrating, sometimes devastating search for their origin story. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, left, who was abandoned and later adopted to the United States at 6 years old, and his wife, Napela, comfort each other as they leave the Busan Metropolitan City Child Protection Center in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024, after searching for documents that could lead to finding his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, right, who was adopted to the United States at 6 years old, talks with diners in the neighborhood where he remembers being abandoned by his mother, in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024. Barthel was posting flyers in the area featuring his photos in the hopes of finding his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Restaurant owner Shin Byung-chul looks from behind a flyer he put up of Kenneth Barthel, who was abandoned in the area as a child and later adopted to Hawaii at 6 years old, at his restaurant in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024. Barthel has visited Korea four times to search for his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, left, helps Shin Byung-chul post a flyer with photos of Barthel at various ages in his life, on the wall of his restaurant in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024, as Barthel's daughter, Amiya, rear, looks on. Barthel's mother had ordered him soup in a restaurant in the area when he was 6 years old, went to the bathroom and never returned. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, who was adopted by a single parent in Hawaii at 6 years old, is hugged by his wife, Napela, at the Sisters of Mary in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024. In the foreground, Sister Bulkeia, left, and Paek Kyeong-mi from Global Overseas Adoptees' Link discuss a flyer designed to uncover the details of Barthel's early life and find his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, adopted from South Korea to Hawaii in 1979 at 6 years old, holds a tablet showing his childhood photo in Busan, South Korea, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Barthel is looking for his birth family in Busan where he believes he was abandoned when his mother ordered soup for him in a restaurant and never returned. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)