SEBLINE, Lebanon (AP) — The war in Gaza was always personal for many Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

Many live in camps set up after 1948, when their parents or grandparents fled their homes in land that became Israel, and they have followed a year's worth of news of destruction and displacement in Gaza with dismay.

While Israeli air strikes in Lebanon have killed a few figures from Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups, the camps that house many of the country's approximately 200,000 refugees felt relatively safe for the general population.

That has changed.

Tens of thousands of refugees have fled as Israel has launched an offensive in Lebanon against Hezbollah amid an ongoing escalation in the war in the Middle East. For many, it feels as if they are living the horrors they witnessed on their screens.

Manal Sharari, from the Rashidiyeh refugee camp near the southern coastal city of Tyre, used to try to shield her three young daughters from images of children wounded and killed in the war in Gaza even as she followed the news “minute by minute.”

In recent weeks, she couldn't shield them from the sounds of bombs dropping nearby.

“They were afraid and would get anxious every time they heard the sound of a strike,” Sharari said.

Four days ago, the Israeli military issued a warning to residents of the camp to evacuate as it launched a ground incursion into southern Lebanon — similar to the series of evacuation orders that have sent residents of Gaza fleeing back and forth across the enclave for months.

Sharari and her family also fled. They are now staying in a vocational training center-turned-displacement shelter run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the town of Sebline, 55 km (34 mi) to the north. Some 1,400 people are staying there.

Mariam Moussa, from the Burj Shamali camp, also near Tyre, fled with her extended family about a week earlier when strikes began falling on the outskirts of the camp.

Before that, she said, “we would see the scenes in Gaza and what was happening there, the destruction, the children and families. And in the end, we had to flee our houses, same as them.”

Israeli officials have said the ground offensive in Lebanon and the week of heavy bombardment that preceded it aim to push Hezbollah back from the border and allow residents of northern Israel to return to their homes.

The Lebanese militant group began launching rockets into Israel in support of its ally, Hamas, one day after the Oct. 7 Hamas-led incursion into southern Israel and ensuing Israeli offensive in Gaza.

Israel responded with airstrikes and shelling, and the two sides were quickly locked into a monthslong, low-level conflict that has escalated sharply in recent weeks.

Lebanese officials say that more than 1 million people have been displaced. Palestinian refugees are a relatively small but growing proportion. At least three camps — Ein el Hilweh, el Buss and Beddawi — have been directly hit by airstrikes, while others have received evacuation warnings or have seen strikes nearby.

Dorothee Klaus, UNRWA’s director in Lebanon, said around 20,000 Palestinian refugees have been displaced from camps in the south.

UNRWA was hosting around 4,300 people — including Lebanese citizens and Syrian refugees as well as Palestinians — in 12 shelters as of Thursday, Klaus said, “and this is a number that is now steadily going to increase.”

The agency is preparing to open three more shelters if needed, Klaus said.

“We have been preparing for this emergency for weeks and months,” she said.

Outside of the center in Sebline, where he is staying, Lebanese citizen Abbas Ferdoun has set up a makeshift convenience store out of the back of a van. He had to leave his own store outside of the Burj Shemali camp behind and flee two weeks ago, eventually ending up at the shelter.

“Lebanese, Syrians, Palestinians, we’re all in the same situation,” Ferdoun said.

In Gaza, U.N. centers housing displaced people have themselves been targeted by strikes, with Israeli officials claiming that the centers were being used by militants. Some worry that pattern could play out again in Lebanon.

Hicham Kayed, deputy general coordinator with Al-Jana, the local NGO administering the shelter in Sebline, said he felt the international “response to the destruction of these facilities in Gaza was weak, to be honest," so “fear is present” that they might be similarly targeted in Lebanon.

Sharari said she feels safe for now, but she remains anxious about her father and others who stayed behind in the camp despite the warnings — and about whether she will have a home to return to.

She still follows the news obsessively but now, she said, “I’m following what’s happening in Gaza and what’s happening in Lebanon.”

A displaced woman reads a Quran, the Muslim holy book, at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Displaced people sit at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

A displaced woman sits with her daughters at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Displaced people sit at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

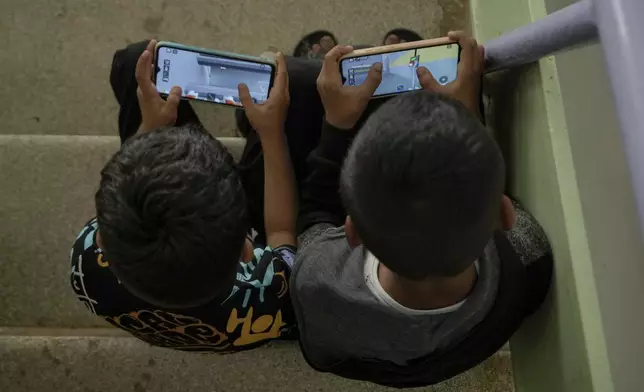

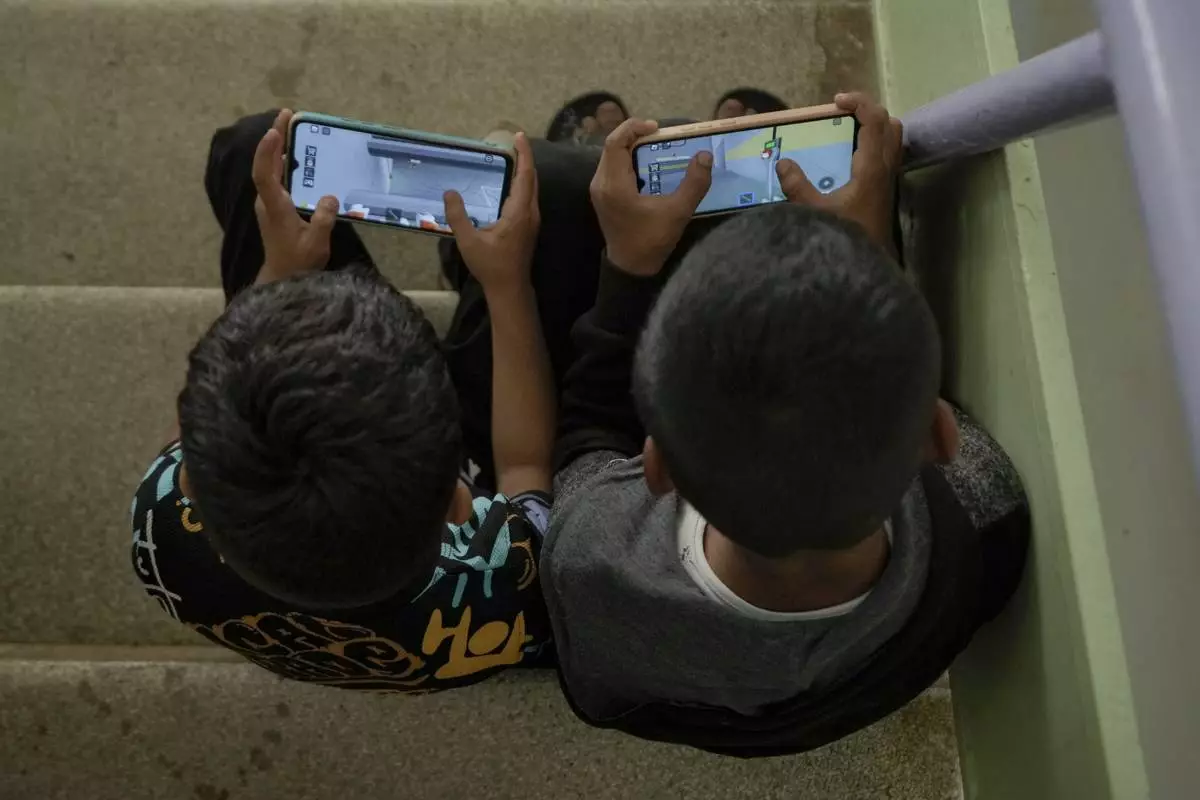

Displaced children play games on their mobile phone at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Turkeya Mohammed hangs her family's laundry at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Displaced people sit at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

Displaced people sit at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)

A displaced woman sits with her daughter at a vocational training center run by the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, or UNRWA, in the southern town of Sebline, south of Beirut, Lebanon, Friday, Oct. 4, 2024, after fleeing the Israeli airstrikes in the south. (AP Photo/Bilal Hussein)