LOS ANGELES (AP) — For more than two decades, the low rent on Marina Maalouf’s apartment in a blocky affordable housing development in Los Angeles’ Chinatown was a saving grace for her family, including a granddaughter who has autism.

But that grace had an expiration date. For Maalouf and her family it arrived in 2020.

Click to Gallery

A general view of Hillside Villa, where Marina Maalouf is a longtime tenant, is seen in Los Angeles, Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, stands for a photo outside her apartment building in Los Angeles on Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

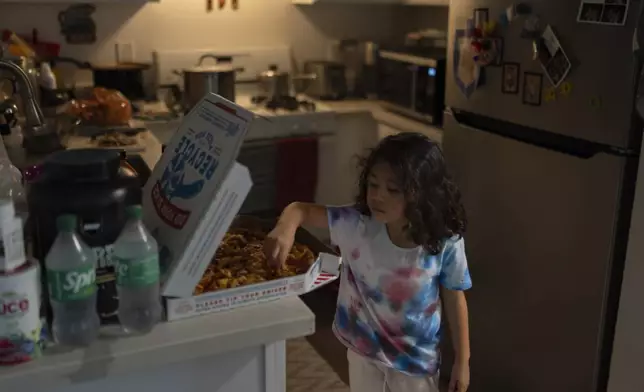

Rubie Caceres, a granddaughter of Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, grabs a slice of pizza in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, scrolls through a digital album in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

A wall in Marina Maalouf's apartment is adorned with family photos as an El Salvadoran flag is draped over an American flag in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rubie Caceres, a granddaughter of Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, enters a bedroom in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rubie Caceres, a granddaughter of Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, plays with a toy camera in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, watches as her granddaughter feeds fish in their apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, stands for a photo inside her apartment building in Los Angeles on Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

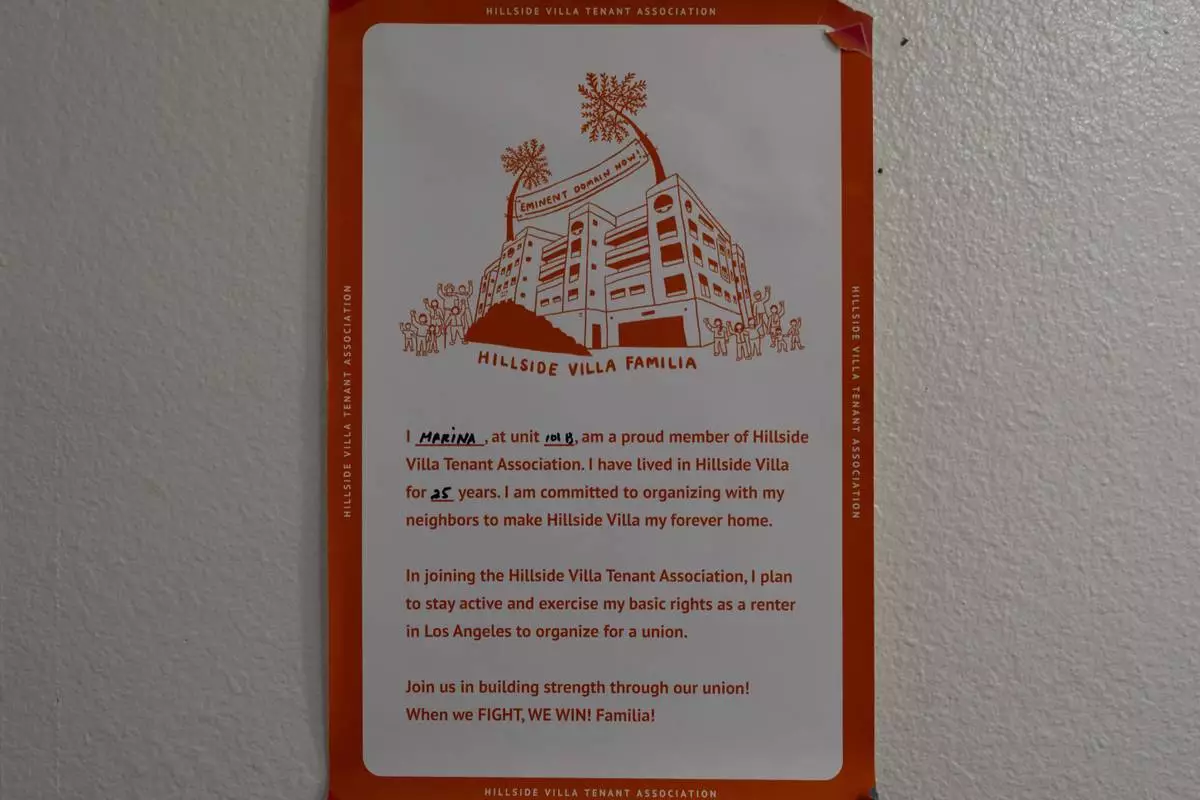

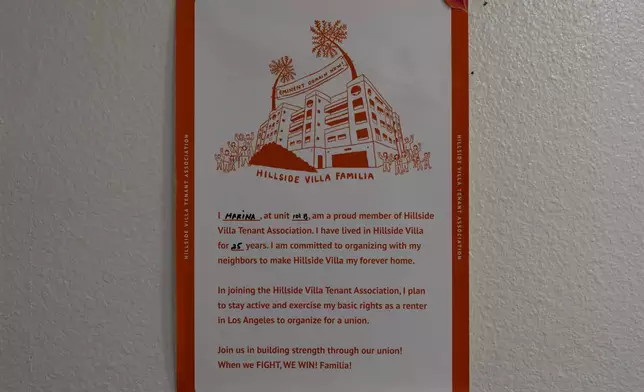

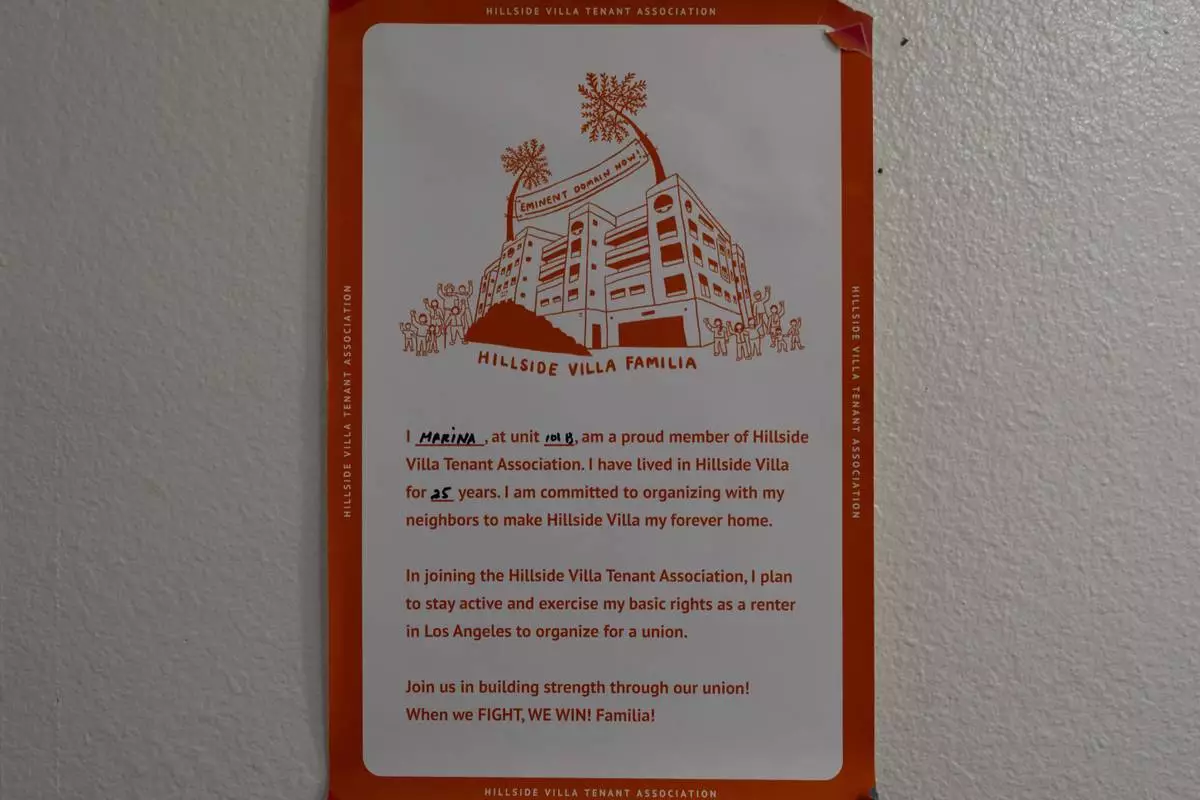

A poster symbolizing solidarity within the tenant community hangs on the wall of Marina Maalouf's apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. Maalouf, a longtime Hillside Villa apartment complex resident, participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, peels potatoes in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, sits on a sofa as her granddaughter eats pizza for lunch in their apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, sits for a photo in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

An aerial view shows Hillside Villa, bottom center, an apartment complex where Marina Maalouf is a longtime tenant, in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The landlord, no longer legally obligated to keep the building affordable, hiked rent from $1,100 to $2,660 in 2021 — out of reach for Maalouf and her family. Maalouf's nights are haunted by fears her yearslong eviction battle will end in sleeping bags on a friend's floor or worse.

While Americans continue to struggle under unrelentingly high rents, as many as 223,000 affordable housing units like Maalouf's across the U.S. could be yanked out from under them in the next five years alone.

It leaves low-income tenants caught facing protracted eviction battles, scrambling to pay a two-fold rent increase or more, or shunted back into a housing market where costs can easily eat half a paycheck.

Those affordable housing units were built with the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, or LIHTC, a federal program established in 1986 that provides tax credits to developers in exchange for keeping rents low. It has pumped out 3.6 million units since then and boasts over half of all federally supported low-income housing nationwide.

“It’s the lifeblood of affordable housing development,” said Brian Rossbert, who runs Housing Colorado, an organization advocating for affordable homes.

That lifeblood isn’t strictly red or blue. By combining social benefits with tax breaks and private ownership, LIHTC has enjoyed bipartisan support. Its expansion is now central to Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris’ housing plan to build 3 million new homes.

The catch? The buildings typically only need to be kept affordable for a minimum of 30 years. For the wave of LIHTC construction in the 1990s, those deadlines are arriving now, threatening to hemorrhage affordable housing supply when Americans need it most.

“If we are losing the homes that are currently affordable and available to households, then we’re losing ground on the crisis,” said Sarah Saadian, vice president of public policy at the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

“It’s sort of like having a boat with a hole at the bottom,” she said.

Not all units that expire out of LIHTC become market rate. Some are kept affordable by other government subsidies, by merciful landlords or by states, including California, Colorado and New York, that have worked to keep them low-cost by relying on several levers.

Local governments and nonprofits can purchase expiring apartments, new tax credits can be applied that extend the affordability, or, as in Maalouf’s case, tenants can organize to try to force action from landlords and city officials.

Those options face challenges. While new tax credits can reup a lapsing LIHTC property, they are limited, doled out to states by the Internal Revenue Service based on population. It's also a tall order for local governments and nonprofits to shell out enough money to purchase and keep expiring developments affordable. And there is little aggregated data on exactly when LIHTC units will lose their affordability, making it difficult for policymakers and activists to fully prepare.

There also is less of a political incentive to preserve the units.

“Politically, you’re rewarded for an announcement, a groundbreaking, a ribbon-cutting,” said Vicki Been, a New York University professor who previously was New York City’s deputy mayor for housing and economic development.

“You’re not rewarded for being a good manager of your assets and keeping track of everything and making sure that you’re not losing a single affordable housing unit,” she said.

Maalouf stood in her apartment courtyard on a recent warm day, chit-chatting and waving to neighbors, a bracelet with a photo of Che Guevarra dangling from her arm.

“Friendly,” is how Maalouf described her previous self, but not assertive. That is until the rent hikes pushed her in front of the Los Angeles City Council for the first time, sweat beading as she fought for her home.

Now an organizer with the LA Tenants' Union, Maalouf isn’t afraid to speak up, but the angst over her home still keeps her up at night. Mornings she repeats a mantra: “We still here. We still here." But fighting day after day to make it true is exhausting.

Maalouf's apartment was built before California made LIHTC contracts last 55 years instead of 30 in 1996. About 5,700 LIHTC units built around the time of Maalouf's are expiring in the next decade. In Texas, it’s 21,000 units.

When California Treasurer Fiona Ma assumed office in 2019, she steered the program toward developers committed to affordable housing and not what she called “churn and burn," buying up LIHTC properties and flipping them onto the market as soon as possible.

In California, landlords must notify state and local governments and tenants before their building expires. Housing organizations, nonprofits, and state or local governments then have first shot at buying the property to keep it affordable. Expiring developments also are prioritized for new tax credits, and the state essentially requires that all LIHTC applicants have experience owning and managing affordable housing.

“It kind of weeded out people who weren’t interested in affordable housing long term,” said Marina Wiant, executive director of California’s tax credit allocation committee.

But unlike California, some states haven't extended LIHTC agreements beyond 30 years, let alone taken other measures to keep expiring housing affordable.

Colorado, which has some 80,000 LIHTC units, passed a law this year giving local governments the right of first refusal in hopes of preserving 4,400 units set to lose affordability protections in the next six years. The law also requires landlords to give local and state governments a two-year heads-up before expiration.

Still, local governments or nonprofits scraping together the funds to buy sizeable apartment buildings is far from a guarantee.

Stories like Maalouf's will keep playing out as LIHTC units turn over, threatening to send families with meager means back into the housing market. The median income of Americans living in these units was just $18,600 in 2021, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

"This is like a math problem,” said Rossbert of Housing Colorado. “As soon as one of these units expires and converts to market rate and a household is displaced, they become a part of the need that’s driving the need for new construction.”

“It’s hard to get out of that cycle,” he said.

Colorado's housing agency works with groups across the state on preservation and has a fund to help. Still, it's unclear how many LIHTC units can be saved, in Colorado or across the country.

It's even hard to know how many units nationwide are expiring. An accurate accounting would require sorting through the constellation of municipal, state and federal subsidies, each with their own affordability requirements and end dates.

That can throw a wrench into policymakers' and advocates' ability to fully understand where and when many units will lose affordability, and then funnel resources to the right places, said Kelly McElwain, who manages and oversees the National Housing Preservation Database. It's the most comprehensive aggregation of LIHTC data nationally, but with all the gaps, it remains a rough estimate.

There also are fears that if states publicize their expiring LIHTC units, for-profit buyers without an interest in keeping them affordable would pounce.

“It's sort of this Catch-22 of trying to both understand the problem and not put out a big for-sale sign in front of a property right before its expiration,” Rossbert said.

Meanwhile, Maalouf's tenant activism has helped move the needle in Los Angeles. The city has offered the landlord $15 million to keep her building affordable through 2034, but that deal wouldn't get rid of over 30 eviction cases still proceeding, including Maalouf's, or the $25,000 in back rent she owes.

In her courtyard, Maalouf's granddaughter, Rubie Caceres, shuffled up with a glass of water. She is 5 years old, but with special needs, her speech is more disconnected words than sentences.

"That’s why I’ve been hoping everything becomes normal again, and she can be safe,” said Maalouf, her voice shaking with emotion. She has urged her son to start saving money for the worst.

“We'll keep fighting,” she said, “but day by day it's hard.”

"I’m tired already.”

Bedayn reported from Denver.

Bedayn is a corps member of The Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

A general view of Hillside Villa, where Marina Maalouf is a longtime tenant, is seen in Los Angeles, Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, stands for a photo outside her apartment building in Los Angeles on Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rubie Caceres, a granddaughter of Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, grabs a slice of pizza in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, scrolls through a digital album in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

A wall in Marina Maalouf's apartment is adorned with family photos as an El Salvadoran flag is draped over an American flag in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rubie Caceres, a granddaughter of Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, enters a bedroom in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Rubie Caceres, a granddaughter of Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, plays with a toy camera in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, watches as her granddaughter feeds fish in their apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, stands for a photo inside her apartment building in Los Angeles on Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

A poster symbolizing solidarity within the tenant community hangs on the wall of Marina Maalouf's apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. Maalouf, a longtime Hillside Villa apartment complex resident, participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa who participated in protests after rents doubled in 2019, peels potatoes in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, sits on a sofa as her granddaughter eats pizza for lunch in their apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Marina Maalouf, a longtime resident of Hillside Villa, sits for a photo in her apartment in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

An aerial view shows Hillside Villa, bottom center, an apartment complex where Marina Maalouf is a longtime tenant, in Los Angeles, Tuesday, Oct. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

MAGDEBURG, Germany (AP) — Germans on Saturday mourned both the victims and their shaken sense of security after a Saudi doctor intentionally drove into a Christmas market teeming with holiday shoppers, killing at least five people, including a small child, and injuring at least 200 others.

Authorities arrested a 50-year-old man at the site of the attack in Magdeburg on Friday evening and took him into custody for questioning. He has lived in Germany for nearly two decades, practicing medicine in Bernburg, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) south of Magdeburg. officials said.

The governor of the surrounding state of Saxony-Anhalt, Reiner Haseloff, told reporters that the death toll rose from two to five and that more than 200 people in total were injured.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz said that nearly 40 of them "are so seriously injured that we must be very worried about them.”

Several German media outlets identified the suspect as Taleb A., withholding his last name in line with privacy laws, and reported that he was a specialist in psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Mourners lit candles and placed flowers outside a church near the market on the cold and gloomy day. Several people stopped and cried. A Berlin church choir whose members witnessed a previous Christmas market attack in 2016 sang Amazing Grace, a hymn about God's mercy, offering their prayers and solidarity with the victims.

There were still no answers Saturday as to what caused him to drive into a crowd in the eastern German city of Magdeburg.

Describing himself as a former Muslim, the suspect shared dozens of tweets and retweets daily focusing on anti-Islam themes, criticizing the religion and congratulating Muslims who left the faith.

He also accused German authorities of failing to do enough to combat what he said was the “Islamism of Europe.” Some described him as an activist who helped Saudi women flee their homeland. He has also voiced support for the far-right and anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

Recently, he seemed focused on his theory that German authorities have been targeting Saudi asylum seekers.

Prominent German terrorism expert Peter Neumann said he had yet to come across a suspect in an act of mass violence with that profile.

“After 25 years in this ‘business’ you think nothing could surprise you anymore. But a 50-year-old Saudi ex-Muslim who lives in East Germany, loves the AfD and wants to punish Germany for its tolerance towards Islamists — that really wasn’t on my radar, " Neumann, the director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence at King’s College London, wrote on X.

“As things stand, he is a lone perpetrator, so that as far as we know there is no further danger to the city,” Saxony-Anhalt’s governor, Reiner Haseloff, told reporters. “Every human life that has fallen victim to this attack is a terrible tragedy and one human life too many.”

The violence shocked Germany and the city, bringing its mayor to the verge of tears and marring a festive event that’s part of a centuries-old German tradition. It prompted several other German towns to cancel their weekend Christmas markets as a precaution and out of solidarity with Magdeburg’s loss. Berlin kept its markets open but has increased its police presence at them.

Germany has suffered a string of extremist attacks in recent years, including a knife attack that killed three people and wounded eight at a festival in the western city of Solingen in August.

Magdeburg is a city of about 240,000 people, west of Berlin, that serves as Saxony-Anhalt’s capital. Friday’s attack came eight years after an Islamic extremist drove a truck into a crowded Christmas market in Berlin, killing 13 people and injuring many others. The attacker was killed days later in a shootout in Italy.

Chancellor Scholz and Interior Minister Nancy Faeser traveled to Magdeburg on Saturday, and a memorial service is to take place in the city cathedral in the evening. Faeser ordered flags lowered to half-staff at federal buildings across the country.

Verified bystander footage distributed by the German news agency dpa showed the suspect’s arrest at a tram stop in the middle of the road. A nearby police officer pointing a handgun at the man shouted at him as he lay prone, his head arched up slightly. Other officers swarmed around the suspect and took him into custody.

Thi Linh Chi Nguyen, a 34-year-old manicurist from Vietnam whose salon is located in a mall across from the Christmas market, was on the phone during a break when she heard loud bangs and thought at first they were fireworks. She then saw a car drive through the market at high speed. People screamed and a child was thrown into the air by the car.

Shaking as she described the horror of what she witnessed, she recalled seeing the car bursting out of the market and turning right onto Ernst-Reuter-Allee street and then coming to a standstill at the tram stop where the suspect was arrested.

The number of injured people was overwhelming.

“My husband and I helped them for two hours. He ran back home and grabbed as many blankets as he could find because they didn’t have enough to cover the injured people. And it was so cold," she said.

The market itself was still cordoned off Saturday with red-and-white tape and police vans every 50 meters (about 54 yards). Police with machine pistols guarded every entry to the market.

Some thermal security blankets still lay on the street.

Christmas markets are a German holiday tradition cherished since the Middle Ages, now successfully exported to much of the Western world.

Saudi Arabia’s foreign ministry condemned the attack on X.

Aboubakr reported from Cairo and Gera from Warsaw, Poland.

Two firefighters walk through a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

A damaged car sits with its doors open after a driver plowed into a busy Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, early Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (Hendrik Schmidt/dpa via AP)

Police stand at a Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, early Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024, after a driver plowed into a group of people at the market late Friday. (Hendrik Schmidt/dpa via AP)

Police stand at a Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, early Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024, after a driver plowed into a group of people at the market late Friday. (Hendrik Schmidt/dpa via AP)

A damaged car sits with its doors open after a driver plowed into a busy Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, early Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (Hendrik Schmidt/dpa via AP)

Police officers and police emergency vehicles are seen at the Christmas market in Magdeburg after a driver plowed into a busy Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (Matthias Bein/dpa via AP)

Security guards stand in front of a cordoned-off Christmas Market after a car crashed into a crowd of people, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday early morning, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

A barrier tape and police vehicles are seen in front of the entrance to the Christmas market in Magdeburg after a driver plowed into a busy Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (Sebastian Kahnert/dpa via AP)

The car that was crashed into a crowd of people at the Magdeburg Christmas market is seen following the attack in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday early morning, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

People mourn in front of St. John's Church for the victims of Friday's attack at the Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (Matthias Bein/dpa via AP)

Police tape cordons-off a Christmas Market, where a car drove into a crowd on Friday evening, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

A police officer stands guard at at a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, where a car drove into a crowd on Friday evening, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Police officers patrol a cordoned-off area at a Christmas Market, where a car drove into a crowd on Friday evening, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Security guards stand in front of a cordoned-off Christmas Market after a car crashed into a crowd of people, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Reiner Haseloff, Minister President of Saxony-Anhalt, center, is flanked by Tamara Zieschang, Minister of the Interior and Sport of Saxony-Anhalt, left, and Simone Borris, Mayor of the City of Magdeburg, at a press conference after a car plowed into a busy outdoor Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (Hendrik Schmidt/dpa via AP)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

A police officer guards at a blocked road near a Christmas Market, after an incident in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services attend an incident at the Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Dörthe Hein/dpa via AP)

Emergency services attend an incident at the Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Heiko Rebsch/dpa via AP)

Emergency services attend an incident at the Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Heiko Rebsch/dpa via AP)

A police officer guards at a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market after an incident in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

In this screen grab image from video, special police forces attend an incident at the Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Thomas Schulz/dpa via AP)

Reiner Haseloff (M, CDU), Minister President of Saxony-Anhalt, makes a statement after an incident at the Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Heiko Rebsch/dpa via AP)

A police officer speaks with a man at a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market after an incident in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

A policeman is seen at the Christmas market where an incident happened in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Heiko Rebsch/dpa via AP)

A firefighter walks through a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after a car drove into a crowd in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Emergency services work in a cordoned-off area near a Christmas Market, after an incident in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

A view of the cordoned-off Christmas market after an incident in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday Dec. 20, 2024. (Heiko Rebsch/dpa via AP)

A police officer guards at a blocked road near a Christmas market after an incident in Magdeburg, Germany, Friday, Dec. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

The car that was crashed into a crowd of people at the Magdeburg Christmas market is seen following the attack in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday early morning, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Security guards stand in front of a cordoned-off Christmas Market after a car crashed into a crowd of people, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday early morning, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Security guards stand in front of a cordoned-off Christmas Market after a car crashed into a crowd of people, in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday early morning, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

The car that was crashed into a crowd of people at the Magdeburg Christmas market is seen following the attack in Magdeburg, Germany, Saturday early morning, Dec. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

Forensics work on a damaged car sitting with its doors open after a driver plowed into a busy Christmas market in Magdeburg, Germany, early Saturday, Dec. 21, 2024. (Hendrik Schmidt/dpa via AP)