EVANSVILLE, Ind. (AP) — It was the day of the “Big Fight” at the police academy, and rookie sheriff’s deputy Asson Hacker groaned as the hulking instructor pressed down on his chest.

Playing the role of a combative suspect, the trainer challenged Hacker to battle like his life was on the line. He punched Hacker, wrapped him in headlocks and tossed him against a padded gym wall.

“C’mon, you got to go home!” another instructor yelled. The message: Hacker needed to fight harder to survive violent encounters on the street.

After seven exhausting minutes, Hacker managed to snap a handcuff on the trainer. Instructors and recruits ringing the gym clapped. Hacker toppled from his knees onto his back.

Within hours, the 33-year-old father of four young sons was dead. A classmate who fought the same instructor shortly after was himself rushed to the hospital with a disabling injury. The public would not be told the full story of that March 2023 day, which authorities described as routine training in which Hacker died of exertion tied to a genetic condition.

The Big Fight at the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy underscores a culture of aggression that persists at some police departments, where officers are taught to view virtually everyone they encounter as a potentially deadly threat. That mindset can lead officers to resort quickly to physical force and weapons on patrol.

A few years before the academy tragedy, four people died over just 14 months on Evansville’s streets after officers used tactics that are not intended to kill – yet have contributed to the deaths of civilians across the nation, an Associated Press investigation found.

That cluster stood out for a mid-sized city among the more than 1,000 deaths AP documented after force such as Tasers and holds. At the same time, the deaths echoed encounters elsewhere in which officers misused force during difficult behavioral and medical emergencies.

AP found a pattern after the fatal incidents involving civilians and at the academy the Evansville Police Department runs: Authorities downplayed the violence, the county coroner who worked 25 years in law enforcement ruled that force did not contribute to the deaths, and no officer was criminally charged.

Video and records that AP unearthed show official narratives omitted key details of the force or mockery officers directed at those who would die. Operating with little independent oversight, Evansville police have been able to shield themselves from criticism, but not always liability. The city paid the parents of one deceased man nearly $1 million to drop their lawsuit and keep quiet.

City officials declined interview requests and didn’t answer a list of questions. A city lawyer said force by Evansville officers has “overwhelmingly been deemed lawful” when challenged in court.

Evansville was among the departments where AP found use-of-force training, tactics and oversight that was similar to practices in cities where the U.S. Department of Justice has raised concerns over the past decade. In June, for example, the DOJ faulted Phoenix police for training and oversight deficiencies that contribute to escalation and force.

Hacker’s relatives feel abandoned and suspicious that the law enforcement family he wanted to join is covering up the role the Big Fight played in his death.

“If they can’t get it right with one of their own,” said Asson’s younger brother, Lij Hacker, “then they’re definitely not going to get it right with the public.”

While Asson Hacker was thrilled to be a rookie deputy, he confided to his brother he was dreading the Big Fight, the culmination of a grueling week of training that already had given him a bruised face and sore ribs.

Hacker had been recruited to join the Vanderburgh County Sheriff’s Office by a deputy who lived next door. A 6-foot-3-inch, 230-pound former college basketball player who became a competitive bodybuilder, Hacker told relatives he felt a calling to help people. As a Black man born in New York City, he would bring diversity to an overwhelmingly white department on Indiana’s border with Kentucky.

Hacker shaved the beard he wore as a coal miner and proudly showed off his uniform to family. He thought wearing the badge would make him a role model for his boys — all under age 12.

First, Hacker had to complete four months at the academy.

For fight day, he was paired with Mike Fisher, a sheriff’s major from a nearby county. A longtime instructor, Fisher had pummeled recruits during a boxing drill two days earlier in what one described as a “beatdown.”

Police academies have long held fight days or similar drills to toughen up rookies before they hit streets, where one misstep could be deadly. Evansville’s was based on a real-world scenario in which an officer ran up the stairs of an apartment building to apprehend two combative suspects.

Hacker paced a hallway before the drill, holding his ribs. When his turn came, he ran up the two-story building’s stairs, punched a bag, ran across the gym and kneed another bag. Then he lay down on the mat so the fight could begin.

A little more than halfway in, video obtained by AP under Indiana’s open records law shows, Hacker wobbled like a fighter in danger of being counted out. He continued listlessly for three more minutes as instructors urged him on and afterward slumped against the ropes of a nearby boxing ring.

About 15 minutes later, four instructors and recruits carried an unconscious Hacker across the gym as another fight continued. They anxiously waited for an ambulance before rushing Hacker to the hospital in the back of a police car.

Instructors told recruits that Hacker was probably just dehydrated or overheated. Among them was Tanner Corum, the Evansville Police rookie next up to face Fisher.

Before his fight, Corum gave a classmate his wife’s number and said to call her if anything happened. He asked for a prayer.

Video shows Fisher sitting and lying on Corum’s chest, holding him to the mat with an arm around his neck and punching him in the stomach as Corum fought to break free. Corum told Fisher he couldn’t breathe, and one recruit later said the restraint “appeared to be suffocating” him. Fisher put him in a headlock and took him back to the mat.

Afterwards Corum couldn’t move his head. His neck felt tight, his right arm trembled. He started walking to his truck to get Tylenol and collapsed.

Summoned to the gym, Corum’s wife drove him to the hospital. As Corum checked in word spread that Hacker was dead.

Hospital doctors concluded that Hacker had rhabdomyolysis, a potentially life-threatening condition sometimes caused by excessive exercise or trauma in which muscles release chemicals that damage the kidneys. Corum had both rhabdomyolysis and a spinal injury in his neck that caused weakness in his limbs. He could not walk without help and was hospitalized for two weeks.

When dozens of uniformed officers gathered at an Evansville church for Hacker’s funeral a week after he died, Corum was up front – in a wheelchair. Vanderburgh County Sheriff Noah Robinson told the crowd they could honor Hacker by committing themselves to the “truth” – a message, he acknowledged later to AP, intended to stop chatter about what caused Hacker’s death.

Evansville police announced Hacker’s death in a news release, saying he and an unidentified second recruit had suffered medical ailments during “routine physical tactics training.” The department vowed to cooperate with an Indiana State Police investigation and pledged transparency.

Many departments around the U.S. face outside investigations into deaths involving officers, but for Evansville it was extraordinary. For decades the department had almost always itself investigated whether officers did anything criminally wrong during fatal encounters.

Even with outside scrutiny, records show some recruits worried the state investigation was influenced by efforts to protect the academy from liability. Investigators repeatedly asked about unfounded claims that steroid use could be to blame and questioned Hacker and Corum’s diets and exercise habits. One recruit was concerned his interview could cause “Hacker’s family to not be compensated.”

Some of the rookie officers said they saw nothing wrong with the training. But others felt investigators ignored the physical force the men endured and a culture in which recruits were pushed to the point of injury. One complained they “were being told a narrative” that absolved the instructors.

A state police spokesperson said the agency conducted a thorough investigation.

Five experts interviewed by the AP said Evansville’s training appeared similar to “defensive tactics” drills used elsewhere, including some that have been linked to deaths and serious injuries.

Spencer Fomby, a longtime use-of-force trainer, questioned the design of Evansville’s scenario, saying police on patrol would very rarely — if ever — fight a larger person on top of them while exhausted without backup or weapons. He said recruits should be taught to avoid trading strikes or engaging in prolonged ground fights, and instead transition to Tasers or other options.

“We’re not supposed to be training police officers to be MMA fighters,” Fomby said.

Had academy instructors stopped when Hacker was clearly exhausted, he would have recovered, said Dr. Randy Eichner, a retired University of Oklahoma professor who has studied exertion-related deaths. While the instructor let up at the end, that was too late, he said: “By then, Asson was fighting a different fight – fighting just to live.”

Determining Hacker’s official cause and manner of death was the job of Vanderburgh County Coroner Steve Lockyear. He was elected after working 25 years at the sheriff’s office that hired Hacker, including as a detective.

“We work very closely and we don’t have any problems,” Lockyear said in an interview of his office’s relationship with local law enforcement.

A pathologist contracted by Lockyear’s office conducted Hacker’s autopsy. During the procedure, police officials showed him videos of the fights and said they reflected normal training, records show.

The coroner announced his ruling weeks later: Hacker died from “exertional sickling due to sickle cell trait.” During exertional sickling, red blood cells become misshapen, causing a drop in blood flow.

Lockyear told AP that combat training had “absolutely” contributed to Hacker’s death by causing him to strenuously exert himself. But he said he ruled the death natural – not a homicide, an accident or undetermined — because Hacker had been born with sickle cell trait.

Sickle cell trait carriers generally have no symptoms, though in rare cases military recruits and athletes have died after suffering heat stroke and muscle breakdown when doing intense exercise. Asson Hacker had known since childhood that he carried the genetic characteristic, but his doctors said it was benign. Exertion had never been a problem for Hacker when he competed in football, basketball or bodybuilding, his brother Lij said.

Dr. Michael Baden, a former New York City medical examiner who has testified in dozens of police-involved deaths, reviewed Hacker’s death for AP. He said several factors likely contributed, including exertion, body blows and dehydration.

He said sickle cell trait may have been a contributing factor but Hacker’s medical records don’t prove that. Testing at the hospital did not reveal any sickling — that was only detected later, at the autopsy, when it would be expected after cells were deprived of oxygen.

“He died as a result of the rough training,” Baden said. “Here they had all these people looking around and nobody said, ‘We ought to stop it.’”

The day the coroner announced his ruling, Sheriff Robinson said officials had been unaware Hacker carried sickle cell trait and his department would start testing recruits for it. Robinson told AP that he saw no misconduct by Fisher and defended the Big Fight.

“It can get violent out there and that violence oftentimes is perpetrated upon us,” the sheriff said. “We have to have the skills to protect ourselves and to protect others.”

Fisher, the academy instructor who is a major with the Knox County Sheriff’s Office, declined an interview. He told investigators that he wanted to put Hacker and Corum into uncomfortable positions that would cause their hearts to race, but that he wasn’t there to hurt anyone.

After the coroner’s ruling, state police closed their investigation. A prosecutor wrote on a form: “Evidence shows no crime was committed.”

“I have seen many fights on body camera and the exercise pales in comparison to the real fights that officers sometimes encounter in the field,” County Prosecutor Diana Moers said later of her office’s decision.

Evansville has not had an officer killed in nearly a century, but some have been seriously injured, including last December when two were attacked while responding to a domestic violence call. The city’s violent crime rate has been higher than the national average, with the closing of manufacturing plants leading to population losses and concerns about poverty, drug use and mental illness.

As a prior recruit at the same academy Hacker attended, Trevor Koontz learned to expect violence. As a rookie on Evansville’s streets, Koontz’s field trainer drilled home that message.

Before patrol shifts, training Officer Matthew Taylor required Koontz to recite a saying out loud: “Whoever I am dealing with may try and kill me. I will not make a mistake so that my wife is a widow.” Koontz, who had served stateside in the Army, would later describe it as a profound reminder of the dangers of his new job.

It was 2019, and Evansville officers had been using force more often than before, according to internal statistics. A longtime Evansville police supervisor blamed anti-police sentiment, saying in sworn testimony, “They’re resisting more than they have in the past. And if you resist more, you have more uses of force.”

Training records show Taylor believed Koontz remained too trusting, and needed to learn that even seemingly friendly people could be hiding a weapon. Taylor stressed to his trainee that Koontz must quickly handcuff and pat down people they encountered.

One September evening, a manager at a Honda dealership called 911, worried that an apparently intoxicated man looking for his truck would stumble into traffic. The man, Edward Snukis, a 55-year-old construction contractor and grandfather, was a 12-hour drive from home in St. Clair, Pennsylvania. He had no criminal history and was unarmed but, his son recalled, had started using methamphetamine after a painful divorce.

Taylor and Koontz found Snukis standing on a sidewalk, his shirt unbuttoned. Hopping out of the patrol car and striding toward Snukis, Koontz ordered him to put his hands on his head, body-camera video shows.

“Why?” asked Snukis. “Why, what’s going on?”

Instead of answering, Koontz grabbed Snukis’ arm and started to pull it behind his back for handcuffing. Koontz would later say he thought Snukis took a “fighting stance,” something that’s not clear from the video.

A startled Snukis swung his arm to break free and hit Koontz, then ran. Taylor fired his Taser, and darts delivering a jolt of electricity caused Snukis to fall.

“Get on the ground or you’ll get it again,” Taylor yelled. Snukis was on the ground. Taylor shocked him a second time.

Snukis managed to get up and run about a block before tripping.

The officers piled on his back and held him face down under their weight, a position that police have long been warned can dangerously restrict breathing. They tried to pull Snukis’ arms from under him. Taylor later said in his report that Snukis tried to grab his holster and groin, so he punched Snukis six times in the head to make him stop.

A backup officer arrived and put his knee on Snukis’ shoulder near his neck as he secured handcuffs. Officers turned Snukis over. Dirt caked his face.

Four minutes after he’d encountered Koontz and two minutes after being held face down, Snukis wasn’t breathing. Officers and paramedics could not revive him.

Witnesses were stunned. A woman told police that Snukis was just standing there before the officer grabbed his arm. “I didn’t see him do anything,” she said.

Her son, Brentlee Spurlock, told police that officers stayed on Snukis too long while he was struggling to breathe. He reiterated that the force seemed excessive in an interview with AP.

Under the Evansville Police Department’s practice of investigating itself, the job of examining the Snukis case fell to Detective Josey Lewis.

Lewis once worked on the department’s bomb squad with training Officer Taylor and occasionally socialized with him outside work, records show.

Taylor and Koontz declined to speak with the detective and exercised their right to remain silent – something that doesn’t happen everywhere after a death, but was routine in Evansville. With help from a lawyer provided by the police union, Taylor and Koontz wrote in their reports that Snukis caused the escalation.

Lewis would later say in a lawsuit deposition he didn’t see anything remarkable in body-camera footage. He never learned Taylor required Koontz to recite the saying – which was not department-wide practice — or that Taylor repeatedly punched Snukis. Lewis never talked to the backup officer who in deposition testimony questioned why officers didn’t try to talk to Snukis first. Both Lewis and police union representatives did not respond to AP's requests for comment.

The department’s investigation turned back on the deceased. Investigators concluded Snukis was aggressive and fought officers immediately – even though Koontz had put his hands on Snukis first.

Two police supervisors who evaluated the Snukis case concluded the force was reasonable. Taylor wrote that his trainee “did a good job of maintaining control during a high-stress situation.”

The pathologist who examined Snukis was the same one who several years later would conduct Hacker’s autopsy. The doctor pointed to methamphetamine in Snukis’ system and an enlarged heart as the cause of death. He added that Snukis’ behavior was consistent with “excited delirium,” a term coined to describe potentially fatal agitation that the medical community now disavows.

Coroner Lockyear ruled Snukis’ death was an accident caused by meth. He acknowledged to AP that it is “extremely dangerous” for officers to pile on suspects who are face down but said that’s not why Snukis died, saying Evansville has long been a “meth capital” and the drug causes aggression. Lockyear also said he would only rule a restraint death a homicide – a death at the hands of another – if officers acted recklessly or showed an intent to kill.

“You can’t blame the police for everything,” he said.

AP’s investigation found that coroners or medical examiners elsewhere have blamed preexisting health conditions or drug use in many deaths that involved significant police force.

The police department cited the coroner’s ruling in closing its investigation as “non-criminal.” While local or state prosecutors in many places review police custody deaths for potential criminal charges and issue public rulings, the Snukis case was never forwarded for a legal examination.

Baden, the former New York City medical examiner, reviewed the Snukis records for AP and said he would have ruled the death a homicide caused by restraint asphyxia. Baden said the level of meth in Snukis was high, but would not normally be fatal. He said video shows Snukis stopped breathing soon after officers put pressure on his back.

The pathologist who conducted Snukis’ official autopsy testified he could not rule out asphyxia as the cause, but added he could not tell since video didn’t clearly show the force. He said if he’d been told that Taylor repeatedly punched Snukis’ head, he would have examined the skull and brain more carefully.

Koontz acknowledged under oath that his body-camera video did not support his written claim that Snukis “approached me yelling and throwing his hands in the air.”

A policing expert hired by the family and an outside expert contacted by AP both said that Koontz made a rookie mistake by quickly trying to handcuff Snukis, rapidly escalating a routine welfare check.

“He was not the aggressor,” Snukis’ son, Ed Jr., said in an interview. “Yes, he was going through a hard time, but everybody goes through hard times. That’s life. The cops had no sympathy for his life at all.”

Neither Koontz nor Taylor faced disciplinary action. But weeks later, at the end of his probationary period, Koontz resigned. Department officials had informed him that his attention to officer safety still fell short. Koontz did not return messages seeking comment.

Taylor, who also did not reply to requests for comment, testified he regretted “that Mr. Snukis’ decisions on that day have caused pain and suffering for his family.”

Earlier this year, a federal judge dismissed the Snukis family’s lawsuit, finding the force was reasonable given Snukis’ resistance. The family has appealed.

Snukis’ death in September 2019 was followed by three other deaths involving Evansville police restraint, according to the AP investigation, done in collaboration with FRONTLINE (PBS) and the Howard Centers for Investigative Journalism.

In February 2020, 25-year-old Dean Smith fled after an Evansville officer pulled over his vehicle to arrest him on a warrant. A police dog caught Smith and bit his legs. Bleeding and handcuffed, Smith told officers he had asthma and couldn’t breathe. An officer told Smith, who was Black, “Boy, you’re being overly dramatic.” Soon after medics arrived, Smith suffered cardiac arrest.

The next month, police responded to a motel where an agitated man had been scaring guests. After Steven Beasley resisted handcuffs, an officer threw him to the ground and his head struck a wall, bystander cellphone video showed. Another shocked Beasley with a Taser while he was handcuffed face down, saying he was kicking and trying to bite an officer. Several officers put pressure on his back and head, at times joking and laughing as Beasley, 37, became unresponsive.

The department said in a news release officers were “attempting to save Mr. Beasley’s life” after a struggle, without mentioning the takedown, the Taser use or the prolonged restraint. Internal reports supported those uses of force.

In November 2020, officers chatted for several minutes while Evan Terhune, hands cuffed behind his back and his face covered by a spit hood, screamed and banged his head against metal in a police van parked outside a hospital. The 20-year-old was hallucinating on LSD, having been shocked with a Taser and arrested after becoming violent at a party and punching an officer.

“It’s not a good day for this guy,” an officer said of Terhune. By the time officers opened the van, he was unresponsive. In a previously unreported legal settlement that AP obtained under a records request, the city agreed earlier this year to pay Terhune’s parents $987,600. Under the terms, the family must keep the amount confidential and never make any “disparaging” statements about Evansville police.

William Harmening, a retired law enforcement officer who wrote a book about officers using excessive force, reviewed all four Evansville deaths in AP’s database. He found officers made mistakes in each, from misusing restraint tactics to delaying immediate medical help.

“You have a department that’s poorly supervised,” he said.

Billy Bolin, who was Evansville’s chief at the time of all five deaths, didn’t respond to interview requests. He left the department earlier this year and is now chief in nearby Henderson, Kentucky.

The coroner ruled that Smith died from complications of sickle cell trait, as he later would with Hacker. He ruled that Beasley’s death was “undetermined” after an autopsy report said he had suffered extensive blunt force trauma to his head and body but also had excited delirium. And he found that Terhune died from self-inflicted head trauma. None of the rulings cited police force or restraint in the cause.

The department closed its investigations of the officers without finding fault, and the county prosecutor’s office said it had no record of reviewing any of the four cases.

The fallout from the training tragedy continues.

Hacker’s estate, represented by his widow, Kourtney Hacker, filed a lawsuit in September alleging the instructor used excessive force and impeded Hacker’s breathing. The lawsuit said the Big Fight amounted to hazing, and the academy failed to have adequate medical personnel available. Another instructor was negligent by encouraging a distressed Hacker to keep fighting and failing to intervene, alleges the suit.

Sheriff Robinson said the lawsuit contained allegations that were “either inaccurate or misleading” and he expects the academy and its instructors to present a robust defense.

Corum notified the city that he may also file a lawsuit. He said he still suffers severe pain in his back, numbness on his left side and neck pain that causes frequent headaches. He resigned from a desk job in the records department he’d gotten because he could not patrol the streets, and a city board later approved his application for a disability pension.

“Everything’s just been life-changing,” said Corum, 29, who lamented how he can’t pick up his young sons for long or run without pain or numbness.

Citing potential litigation, Keith Vonderahe, an outside lawyer representing the city, directed Evansville’s mayor and police chief to cancel interviews with AP.

“We’re not aware of any facts or evidence that our training procedures caused the tragic death of Mr. Hacker or Mr. Corum’s injuries,” Vonderahe said.

Lij Hacker, who once wanted to join his brother to fight crime in Evansville, has asked the FBI to investigate. He said he recently met with an agent but the status of any inquiry is unclear.

What Lij Hacker wants now is for people to see how his brother died, and accountability and change within law enforcement in Evansville.

“If this slips through the cracks and no one is held accountable,” he said, “the justice system has failed us.”

Seewer reported from Toledo, Ohio.

This story is part of the ongoing investigation “Lethal Restraint” led by The Associated Press in collaboration with the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism programs and FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes an interactive story, database and the film “Documenting Police Use Of Force.”

The Associated Press receives support from the Public Welfare Foundation for reporting focused on criminal justice. This story also was supported by Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips

A garrison flag is adjusted before the funeral of Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Deputy Asson Hacker at Christian Fellowship Church on the evening of March 9, 2023. (Denny Simmons/Evansville Courier & Press via AP)

This photo provided by the Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Office shows Deputy Asson Hacker, who died March 2, 2023. (Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Office via AP)

FILE - This photo provided by the family shows Steven Brad Beasley. The 37-year-old died March 26, 2020, after being restrained by Evansville, Ind., police officers. (Amanda Ortiz via AP, File)

In this image from Evansville Police Department body-camera video, officers restrain Steven Beasley face down, in Evansville, Ind., on March 25, 2020. Vanderburgh County Coroner Steven Lockyear ruled that Beasley's death was "undetermined" in both cause and manner after an autopsy report said he had suffered extensive blunt force trauma to his head and body but also had "excited delirium." (Evansville Police Department via AP)

FILE - This photo provided by the family shows Evan Terhune. The 20-year-old died Nov. 17, 2020, after being held in a police van by Evansville, Ind., officers. (Gerald Terhune via AP, File)

This image from Evansville Police Department video shows Evan Terhune, hands cuffed behind his back and his face covered by a spit hood, in the back of a police van in Evansville, Ind., on Nov. 14, 2020. By the time officers opened the van, he was unresponsive. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

In this image from video made by the Evansville Police Department, police recruit Tanner Corum, below, undergoes training with Mike Fisher, a sheriff's major from a nearby county, during "Big Fight" day for the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy in Evansville, Ind., on March 2, 2023. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

This family photo shows Tanner Corum at the Encompass Health Deaconess Rehabilitation Hospital in Newburgh, Ind., in March 2023, days after the Evansville, Ind., Police Department recruit was injured during "Big Fight " day training. (Courtesy Corum family via AP)

In this image from video made by the Evansville Police Department, police recruit Tanner Corum, foreground right, undergoes training with Mike Fisher, a sheriff's major from a nearby county, during "Big Fight " day for the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy in Evansville, Ind., on March 2, 2023. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

Club Bushido, the site for “Big Fight” day for the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy, is seen in Evansville, Ind., on June 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Ryan J. Foley)

Evansville Police vehicles are parked on a street in Evansville, Ind., on June 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Ryan J. Foley)

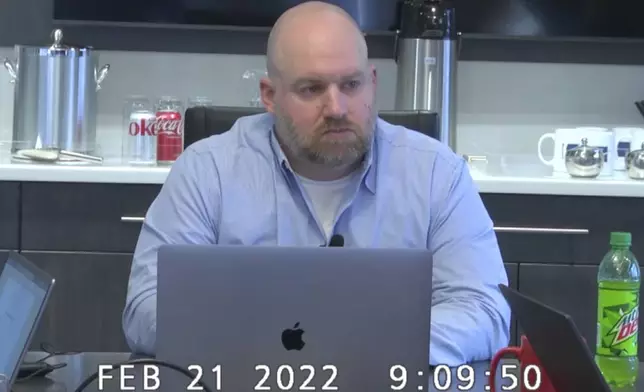

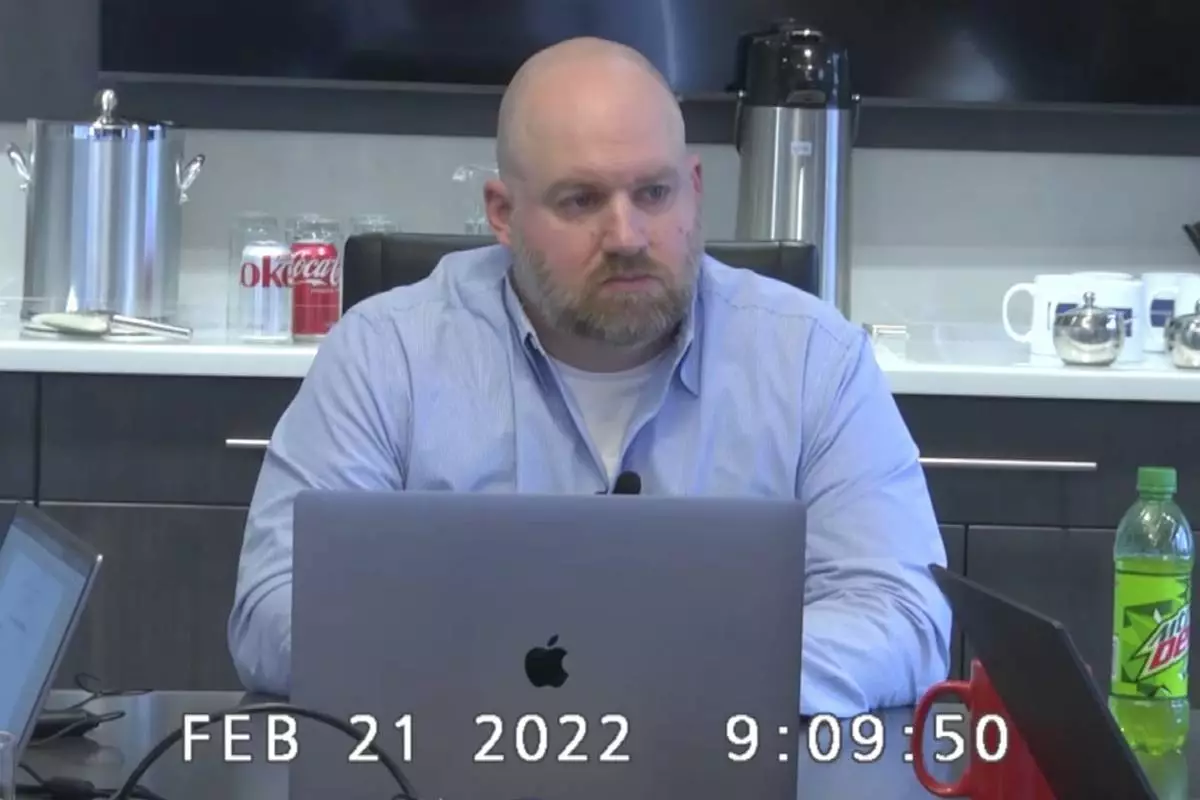

In this image from U.S. District Court, southern district of Indiana deposition video, Evansville Police Officer Matthew Taylor is questioned about the death of Edward Snukis in Evansville, Ind., on Feb. 21, 2022. (AP Photo)

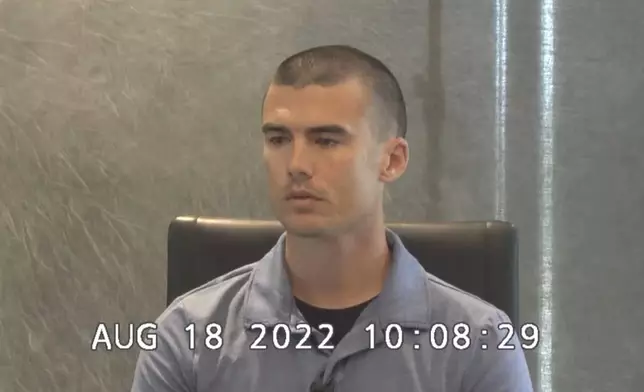

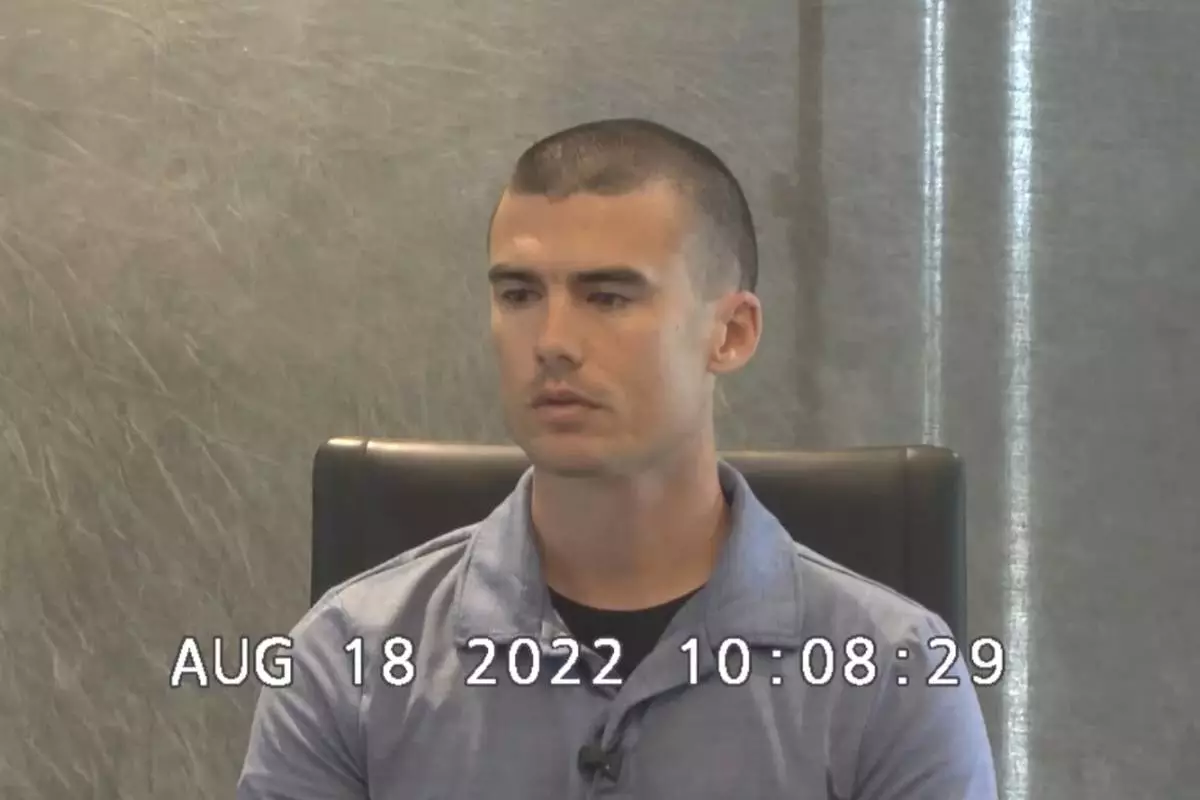

In this image from U.S. District Court, southern district of Indiana deposition video, Evansville Police Officer Trevor Koontz is questioned about the death of Edward Snukis in Evansville, Ind., on Aug. 18, 2022. (AP Photo)

This photo provided by the family shows Edward Snukis with two of his grandchildren at home in Schuylkill Haven, Pa., on Aug. 20, 2019. Snukis, 55, died the next month after police officers in Evansville, Ind., shocked him with a Taser, punched him and held him face down. (Jill Snukis via AP)

In this image from video provided by the Evansville Police Department, Edward Snukis, bottom center, is restrained by officers in Evansville, Ind., on Sept. 13, 2019. Snukis, 55, died after police officers shocked him with a Taser, punched him and held him face down. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

This photo provided by the family shows Edward Snukis, center, with four of his grandchildren and his son, Ed Snukis Jr., during a trip to Atlantic City, N.J., on Sept. 3, 2019. Snukis died later in the month after police officers in Evansville, Ind., shocked him with a Taser, punched him and held him face down. (Jill Snukis via AP)

In this image from video provided by the Evansville Police Department, Officer Matthew Taylor fires a Taser at Edward Snukis in Evansville, Ind., on Sept. 13, 2019. Snukis, 55, died after an encounter in which officers shocked him with a Taser, punched him and held him face down. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

Lij Hacker holds a coin inscribed with the name of his late brother, Asson Hacker, during an interview in Bloomington, Ind., on June 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Darron Cummings)

Lij Hacker wipes away a tear while talking about his late brother, Asson Hacker, during an interview in Bloomington, Ind., on June 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Darron Cummings)

In this image from video made by the Evansville Police Department, rookie sheriff’s Deputy Asson Hacker, background left, lies unconscious after training with Mike Fisher, a sheriff's major from a nearby county, as another recruit undergoes training, foreground, during "Big Fight " day for the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy in Evansville, Ind., on March 2, 2023. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

In this image from video made by the Evansville Police Department, rookie sheriff’s Deputy Asson Hacker, below left, undergoes training with Mike Fisher, a sheriff's major from a nearby county, during "Big Fight " day for the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy in Evansville, Ind., on March 2, 2023. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

In this image from video made by the Evansville Police Department, rookie sheriff’s Deputy Asson Hacker, below, undergoes training with Mike Fisher, a sheriff's major from a nearby county, during "Big Fight" day for the Southwest Indiana Law Enforcement Academy in Evansville, Ind., on March 2, 2023. (Evansville Police Department via AP)

In this photo provided by the family, Asson Hacker, right, sits with his wife and their children during a trip to the Mayse Farm pumpkin patch in Evansville, Ind., in October 2022. (Family photo via AP)

Friends and family of Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Deputy Asson Hacker gather after the procession arrives at Christian Fellowship Church in Evansville, Ind., for his visitation and funeral, on March 9, 2023. (MaCabe Brown/Evansville Courier & Press via AP)

Lij Hacker holds a photo of his late brother, Asson Hacker, during an interview in Bloomington, Ind., on June 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Darron Cummings)

The casket of Vanderburgh County Sheriff's Deputy Asson Hacker is escorted to a hearse outside Boone Funeral Home in Evansville, Ind., on March 9, 2023. (MaCabe Brown/Evansville Courier & Press via AP)