WASHINGTON (AP) — Americans will cast roughly 160 million ballots by the time Election Day comes to a close — in several different ways, including many submitted a few weeks before polls even open.

They will choose a president, members of Congress and thousands of state lawmakers, city council members, attorneys general, secretaries of state — and in Texas, a railroad commissioner who has nothing to do with the trains.

This year’s election also comes at a moment in the nation’s history when the very basics of how America votes are being challenged as never before by disinformation and distrust.

It can be tough to make sense of it all. To help better understand the way America picks its president and its leaders — all the way down the ballot — The Associated Press offers the following thoughts on the Top 25 people, places, races, dates and things to know about Election Day. A guidebook, of sorts, to American democracy as it nears its 250th birthday.

It's said that every presidential election makes history. Perhaps. But while some are destined to be included in the history books, others become the subject of books all of their own. Put 2024 down to get a whole shelf at the library. Will Americans choose to return Donald Trump to the White House, electing a former president to a new term for only the second time — and picking for the first time a person convicted of a felony to sit behind the Resolute Desk? Or will voters decide Kamala Harris ought to be the nation's first woman to take up office in the Oval Office, a candidate who didn't win a single primary yet landed at the top of her party's ticket by acclamation. No list of the Top 25 things to know about this year's general election can begin without an acknowledgment that no matter who America chooses, Trump and Harris will make history this Election Day. (Or a few days later.)

There might not be anyone as all-in on returning Trump to the White House as Elon Musk, the world’s richest person. “President Trump must win to preserve the Constitution. He must win to preserve democracy in America,” the founder of SpaceX and Tesla told a rally crowd in early October when Trump returned to the site of his first attempted assassination in Pennsylvania. Along with his unfathomable personal wealth, Musk’s ownership of X, formally known as Twitter, gives him an unprecedented ability to try and convince voters of his belief that electing Trump is a “must-win situation.” Musk is spending heavily on get-out-the-vote efforts and using his perch as X’s CEO to amplify misinformation and push into millions of timelines his argument that the country will not survive should Kamala Harris win the White House. It’s a foreboding message that seems to get bleaker by the day – and Musk knows it. “As you can see, I am not just MAGA,” he told Trump’s backers from the rally stage. “I am Dark MAGA.”

The founder of Win With Black Women, Jotaka Eaddy has for the past four years hosted Sunday evening video conferences on Zoom to chat politics. On July 21, she couldn’t get into her own meeting. Earlier that day, Joe Biden dropped out of the presidential race and endorsed Kamala Harris as his replacement to be the Democratic nominee, and once Zoom changed some settings, 44,000 people were online and ready to talk about it. It was a pep talk and a telethon. People prayed and sang. About an hour after the Zoom started, Star Jones shared a donation link and by early the next morning they had raised more than $1 million. The meeting spawned a domino effect as Eaddy turned a tool made essential by the coronavirus pandemic into an essential place for Harris' supporters to gather. Soon, Black men and white women and white dudes and Taylor Swift fans were logging on. “It has allowed us to organize in a way to bring people together that otherwise would not connect,” Eaddy said.

Now that how a ballot is cast is as much of a red/blue choice as the candidate getting the vote, figuring out who will win a close election often depends on knowing the kind of ballots left to be counted. Garrett Archer, a former analyst at the Arizona Secretary of State’s office who is now a data journalist, was one of the first of Twitter’s election seers to understand how nit-picky those details can be. Were the advance votes still to be counted cast in person, mailed or left at a drop box? How soon before Election Day did those mail ballots arrive? Or might those mail votes actually be “late earlies” dropped off at a polling place? Archer goes deep into those details in his job with ABC’s Phoenix affiliate, but most of us will get his analysis of Arizona’s election results online, as we wait every afternoon after Election Day for his trademark Tweet that begins: “Maricopa incoming...”

About a week after Election Day, Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows is likely to star in a livestream via laptop webcam to announce results of ranked choice voting. The instant-runoff system, used when no candidate initially wins an outright majority, might be a downballot novelty if not for the state’s 2nd Congressional District. Behind by about 2,000 votes in 2018, Democrat Jared Golden emerged the winner and ousted the GOP incumbent once the ranked choice process awarded him the votes of two trailing independents. Maine also awards two of its Electoral College votes by congressional district, and while it may be unlikely, the road to 270 electoral votes could theoretically end with ranked choice results in Maine’s 2nd District. In that case, should Golden’s come-from-behind win of 2018 repeat itself, it would fall to Bellows to announce that ranked choice voting had put a second-place finisher into the White House.

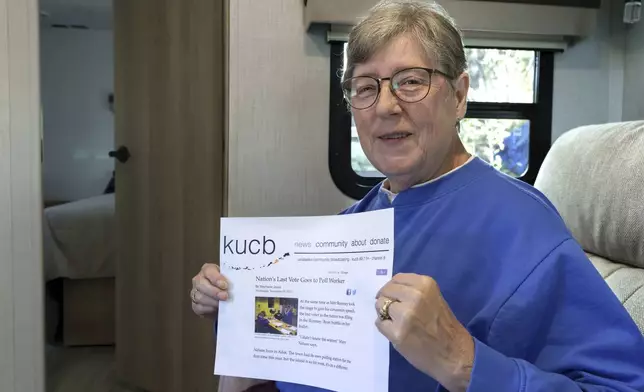

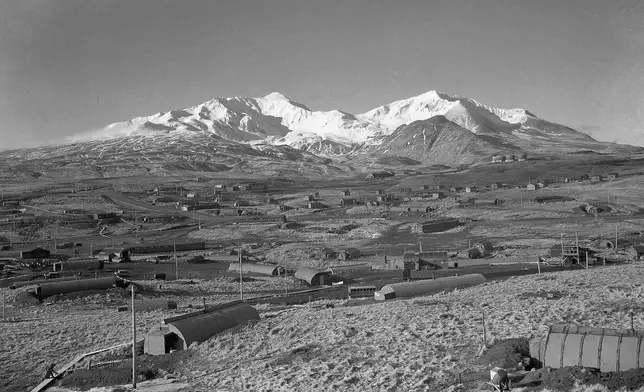

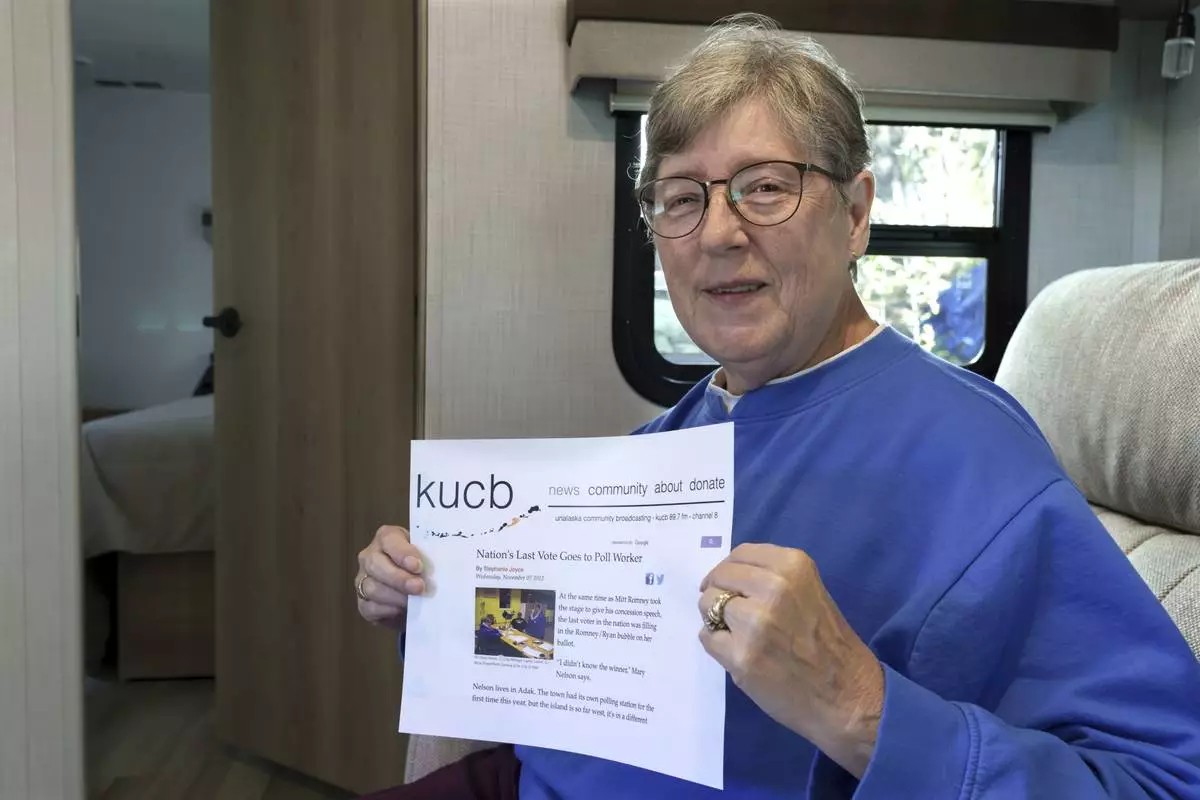

On an Aleutian island closer to the Russian border than mainland Alaska and more than 4,000 miles from the White House, the question isn’t who wins on Election Day. It’s who will be the very last American to vote. “People have a little bit of fun on that day, because, I mean, realistically everybody knows the election’s decided way before we’re closed,” said Layton Lockett, the city manager in Adak, Alaska. The country’s last polling place to close is the only one still open from midnight ET to 1 a.m., when things wrap up on the island and former World War II military base. The honor of being the last voter was Mary Nelson’s in 2012, when the community of a few hundred people did away with early voting in favor of casting ballots in person. She was a poll worker that Election Day, too, meaning her historic moment was short-lived. “When I opened the curtain to come back out, the city manager took my picture … and they were waiting for us in Nome to call with our vote count,” she said.

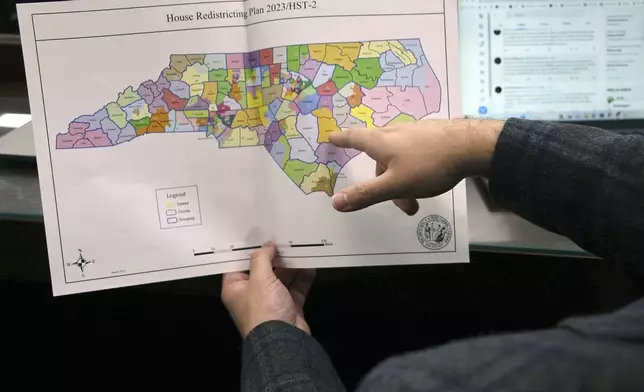

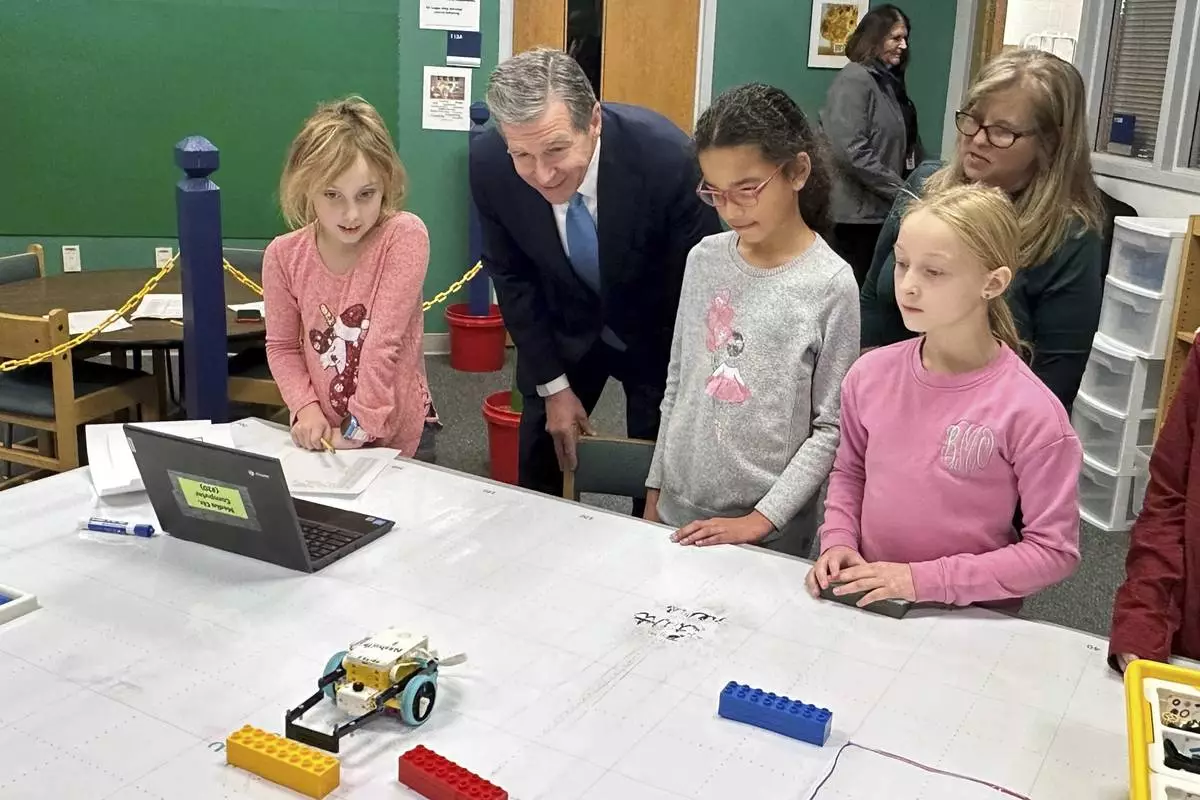

Out of more than 500 counties in the seven battleground states in this year’s election, only 10 voted for Trump in 2016 before flipping to Biden in 2020. The first to complete its count this Election Day ought to be North Carolina’s Nash County, which by 10 p.m. ET could provide an early indication of which candidate is performing best among the swing voters likely to decide a closely contested White House. That’s especially true should there be a decisive winner in the community northeast of Raleigh, unaffected by Hurricane Helene. Two decades have passed since any presidential candidate won Nash by more than a point. Confirmation won’t come for hours (or days), but more intelligence will arrive about a half hour later when North Carolina’s other Trump-Biden county — New Hanover on the state’s Atlantic Coast — should wrap up its count. The other eight counties to watch: Erie and Northhampton in Pennsylvania; Maricopa in Arizona; Kent, Saginaw and Leelanau in Michigan and Sauk and Door in Wisconsin.

There’s more to Arizona than Maricopa County. Seriously! Yes, it’s true that Biden eked out a win in 2020 among the more than 60% of Arizona voters who live in the sprawling home of Phoenix and its suburbs. But Biden may not have won Arizona and its 11 electoral votes without his win in Apache County, where he beat Trump by 11,851 votes out of roughly 35,000 cast. His statewide margin? Just 10,457. Apache County is far from the typical Democratic urban stronghold. Much of the rural county is part of the Navajo Nation, and it also includes lands belonging to the Apache people who gave the county its name. In all, more than 70% of people living there are Native American. America’s indigenous population is often overlooked in presidential elections: the states with the largest percentages of Native people – Alaska, New Mexico, Oklahoma and South Dakota – are not often competitive. Arizona’s emergence as a battleground makes the voters in Apache County — and the roughly 5% of Arizonans who are Native American — a potential factor in this year’s election.

Trump won Wisconsin by about 20,000 votes in 2016 – and he and the country had to wait on Milwaukee County to know which way that margin would fall. The state’s largest county and Democratic stronghold is one of a handful in Wisconsin that releases results of mail ballots all at once, rather than combining them with other ballots counted at precinct polling places. In 2016, confirmation there weren't enough mail votes left to count in the City of Milwaukee to flip the race from Trump to Hillary Clinton allowed AP to declare the Republican the winner of the state – and the White House. In the 2022 midterms, it was only when AP confirmed there were no ballots remaining to be counted in Milwaukee and Dane County, Wisconsin’s other largest source of Democratic votes, that it was able to say incumbent Republican Ron Johnson would return to the Senate. Milwaukee might not be among the final counties in Wisconsin to report its results this year, but don’t count out its chances to be the decisive county once it does in this crucial battleground state.

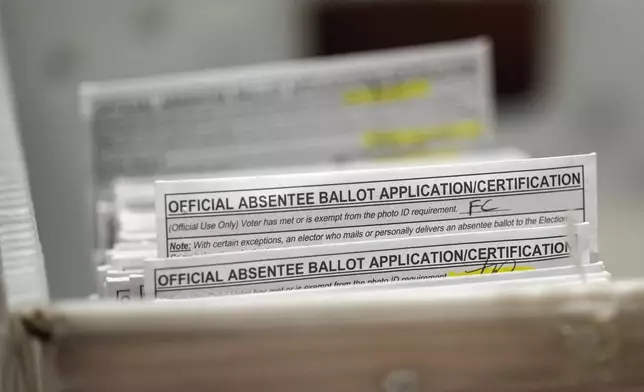

Election officials nationwide found no cases of fraud, vandalism or theft related to the use of drop boxes that that could have affected the outcome of the 2020 presidential election. And yet no place in this year’s election may face more scrutiny than the drop box – a tool designed to make voting easier that’s become the source of conspiracy theories that they played a role ( they didn’t ) in stealing the election from Trump ( it wasn’t ). Several states have enacted laws restricting their use since 2020, while in others they remain the subject of fascination. The Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed itself in July and dumped a ruling that limited drop boxes to only election clerks’ offices. Prosecutors are currently investigating the removal of Wausau’s drop box last month by the mayor without consulting with the city clerk. Election officials typically have detailed processes to ensure the security of ballots left in drop boxes, which are often monitored remotely by camera. Still, drop boxes remain a place where opponents wrongly believe their vote is neither safe nor secure.

There are 538 electoral votes to win from the 50 states and the District of Columbia, but the Trump and Harris campaigns are seriously contesting only seven states this year as battlegrounds: Arizona and Nevada out West, North Carolina and Georgia in the South, Michigan and Wisconsin amid the Great Lakes and Pennsylvania as the final boss. Eight years ago, Pennsylvania was the last state called for Trump before he won the election by winning in Wisconsin in the early morning hours after Election Day. Four years ago, Biden's win there four days after polls closed — by roughly 80,000 votes out of more than 6.8 million cast — was the difference. Both presidential hopefuls can get to the 270 electoral votes needed to win the White House without the Keystone State, but their path to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue gets a whole lot easier if they grab Pennsylvania's 19 electoral votes along the way.

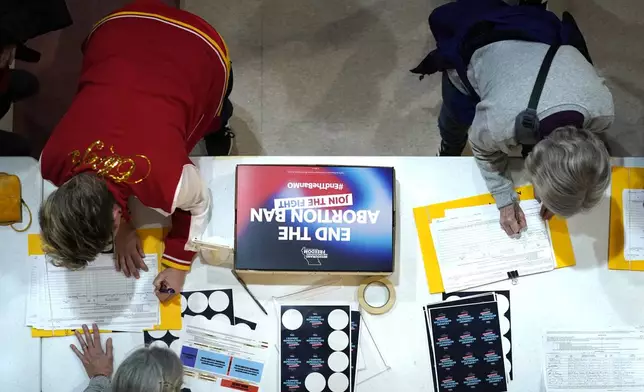

Supporters of abortion rights are 7-for-7 in statewide votes since the U.S. Supreme Court “ returned to the people and their elected representatives ” the ability to decide on the legality of abortion. Come Election Day, voters in nine more states will get the chance via ballot measure to do the same. The states range from the reliably blue (Colorado, Maryland) to the resolutely red (South Dakota, Missouri, Nebraska ), with a few presidential battlegrounds and/or states with key races for U.S. Senate – Arizona, Nevada and Montana – in between. And then there’s Florida, a state Hillary Clinton hoped would provide her with a powerful push into the White House. Instead, the Sunshine State was in 2016 (and again in 2020) a cornerstone of Trump’s Electoral College count. A Trump loss in Florida would undoubtedly sink his bid to return to the White House, but it’s hardly clear that the chance to vote on social issues – even one as potent as abortion – can sway enough voters to truly affect an outcome at the top of the ticket.

Republicans can likely hold the U.S. House of Representatives even if they lose a couple of seats in New York, where a messy redistricting process two years ago helped the GOP win six districts carried by Biden. But if those losses include freshman Rep. Marc Molinaro in the state’s 19th District, it will make for an uncomfortable election night for House Speaker Mike Johnson. Molinaro has styled himself as a pragmatist as he seeks reelection for the first time, avoiding the circus of former GOP Rep. George Santos in New York’s 3rd District – a seat his party has already lost – and the inconveniently timed headlines of rising party star and 17th District Rep. Mike Lawler. Democrat Josh Riley, who nearly won the district in 2022, has raised more money than Molinaro ahead of their November rematch, as Democrats run candidates nationwide who came up just short in the 2022 midterms. If that’s a winning strategy in New York’s 19th District and elsewhere, the celebrations might be the most raucous in Brooklyn at the election night party of New York 8th District Rep. Hakeem Jefferies: the Democratic leader and House Speaker-in-waiting.

Pay enough attention to politics and you’ll have heard the bit about Democrats being one election away from winning in Texas. Then Election Day arrives and Republicans have the cattle while Democrats are once again holding their hat. Is this the year that changes? Democrats say they’re investing serious cash into the state with the hope that an unpopular incumbent (Sen. Ted Cruz) is at risk to a rising star (former NFL player and current Rep. Colin Allred). Sound familiar? Six years ago, Cruz was an unpopular incumbent running against a rising Democratic star from the U.S. House named Beto O’Rourke. Some say O’Rourke ran the perfect campaign…and Cruz won by a comfortable 2.6 points. It’s been 30 years since a Democrat won statewide in Texas, so maybe the odds are better for Democrats in Florida? They’re spending money there, too, to try and take down incumbent Sen. Rick Scott. Ask the GOP what to make of these moves and they’ll tell you Democrats need that kind of dramatic upset to keep control of the Senate.

John Duarte might be in one of the closest races of the cycle – and possibly faces the longest waiting time to find out if he’s returning to Congress. The California Republican won his 2022 race by 564 votes in a race that was so close that the AP needed until the first week of December to declare Duarte the winner. Now he has to do it all again: He faces a rematch in the state’s 13th Congressional District against former state Assemblyman Adam Gray. California’s count takes so long in large part because the state conducts its elections entirely by mail. In the 13th, there are also no major cities – no L.A., no Bakersfield, not even Fresno – that would provide enough votes at the beginning of the night to make clear who has won. If the House majority comes down to Duarte’s race, the nation’s attention will focus on a long count in five counties of California’s agricultural Central Valley.

The first Tuesday after the first Monday in November is Election Day, established in 1875 under 2 U.S. Code § 7 for the election “in each of the States and Territories of the United States, of Representatives and Delegates to the Congress.” In modern U.S. elections, Election Day is perhaps best thought of as the LAST day of the general election: it's the final chance for voters to cast ballots in person, for mail ballots to arrive and be counted, or, in some states, the day by which mail ballots must be postmarked.

Three weeks later comes the last day a mail ballot can arrive in Washington state and still be counted — Nov. 25 is the latest deadline for any state that accepts votes cast by mail to arrive with an Election Day postmark. In all, 17 states and the District of Columbia allow mail ballots to arrive after Election Day, while 32 others require they be in the ballot box on Election Day. Only Louisiana requires mail ballots to arrive early in order to be counted — the deadline there for mail ballots is the day before Election Day.

After supporters of Trump stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, in an insurrection that aimed to overturn his loss to then-President-elect Joe Biden, Congress updated the Electoral Count Act to, among other things, establish the date by which every state's governor must certify the results of the presidential election and submit their slate of electors. Any legal challenges should then be completed by Dec. 16, because those members of the Electoral College will vote the next day.

Wait, there's another election day? Indeed! The Constitution says it’s not the people who pick a president, but rather a group of “electors” as selected by each state for the job. But the founders also wrote that states get to decide how to pick their members of the Electoral College, and almost all require they vote for the winner of their state's popular vote (Maine and Nebraska do it just a little differently). This ritual takes place about a week before Christmas, the deadline for the electors' cast ballots to arrive in Washington.

More ceremony in early January as the members of the 119th Congress, having taken office a few days earlier, count those Electoral College ballots under the rules of the updated Electoral Count Act. Objections are still possible, but much harder to raise, and the revised law makes plain the vice president is there only to announce the results as president of the Senate. Once the electoral votes are officially cast and counted, the final step of the election comes at the new president’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 2025.

Almost all of the roughly 160 million ballots that will be cast in this year’s election will be made of paper. And almost all will be counted by machine. Election officials say without such machines, counting those ballots by hand would take much longer, cost taxpayers far more and result in errors that would then take even more time and money to fix. “Human beings are really bad at tedious things, and counting ballots is among the most tedious things we could do,” said Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Charles Stewart. “Computers are very good at tedious things. They can count very quickly and very accurately.” Still, the desire to have humans involved in the process lingers. Officials in Georgia remain at odds over a recent directive from the state's election board requiring poll workers to count the total number of ballots by hand.

At The Associated Press, a race is “too early to call” if election officials are still tabulating votes and there is no clear winner. Regardless of how tight the margin may be between the leading candidates, AP won’t say a race is “too close to call” unless election officials have tallied all outstanding ballots — save for provisional ballots and late-arriving mail and absentee votes — and the winner still remains unclear. In those cases, it's likely AP won’t be able to say who has won until election officials certify the results — a process that may take up to several weeks after Election Day. By the way, elections headed to a recount aren’t automatically “too close to call.” In fact, depending on how many votes separate the trailing candidates from the leader, AP may declare a winner even if a recount is possible.

Here’s the thing about recounts: They might be required by law, they might be requested by a candidate, they might be ordered by a court. But they’re not very likely to do anything but drag out the inevitable. “Recounts are shifting a very small number of votes,” said Deb Otis of the nonpartisan organization Fair Vote. “We’re going to see recounts in 2024 that are not going to change the outcome.” They almost never do. In the 36 recounts of a statewide general election since America’s most famous recount in 2000, none moved the margin by more than a few hundred votes. The average change? Just 0.03 percentage points. The biggest? A move of 0.11 points in the 2006 race for Vermont state auditor – a rare race that did flip as a 137-vote lead in the initial count for Republican Randy Brock became a 102-vote recount win by Democrat Thomas Salmon. “The count is pretty accurate because the machines work,” said former Arizona election official Tammy Patrick. “We have recounts … to make sure we got it right.” As hopeful trailing candidates will soon learn, the first count almost always is.

Looking for “precincts reporting” when watching as results are reported in this year’s election? Chances are, you’ll find an estimate of “ expected vote ” instead. The Associated Press and other news organizations have moved away from precincts reporting as a measure of election turnout for several reasons – the fact that well more than half of voters no longer cast their ballot in person at a neighborhood “precinct” on Election Day chief among them. Instead, AP will estimate how much of the vote election officials have counted – and how many ballots they have left to count – based on a number of data points, including details on advance ballots cast, registration statistics and turnout in recent elections. Those estimates will change as votes are counted and more information about the exact number of ballots cast becomes available. AP’s estimates of ballots cast won’t reach 100% until election results are certified as final and complete.

More often than not, in a nation as evenly divided as the United States, not on Election Day — or, at the least, not on Election Day on the East Coast. Since it took 36 days for George W. Bush's win in the 2000 presidential race to play out in Florida and before the Supreme Court, only in Barack Obama's two victories has AP declared a White House winner before midnight Eastern Time. Trump didn't win until 2:29 a.m. ET in 2016 and he didn't lose in 2020 until the Saturday morning after Election Day — that's how long it took for Biden to claim 270 electoral votes by emerging as the clear winner in Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the sheer number of U.S. Representatives from California — a state where officials will be counting mail ballots for weeks — could make for a long wait to know which party will control the House. The election for Speaker? That's a whole other matter.

The AP Elections Top 25 was reported by Leah Askarinam, Christina A. Cassidy, Christine Fernando, Meg Kinnard, Chris Megerian, Geoff Mulvihill, Stephen Ohlemacher, Emily Swanson, Mark Thiessen and Robert Yoon.

Read more about how U.S. elections work at Explaining Election 2024, a series from The Associated Press aimed at helping make sense of the American democracy. The AP receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - The Nash County Courthouse is in Nashville, N.C., on Tuesday, Oct. 28, 2014. (Chris Seward/The News & Observer via AP, File)

FILE - In this April 2015 photo, the buildings of the former Adak Naval Air Facility sit vacant in Alaska. (Julia O'Malley/Anchorage Daily News via AP)

FILE - This combination of photos shows Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump, left, and Democratic presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris during an ABC News presidential debate at the National Constitution Center, Tuesday, Sept. 10, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon, File)

FILE - Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk walks to the stage to speak alongside Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump at a campaign event at the Butler Farm Show, Saturday, Oct. 5, 2024, in Butler, Pa. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon, File)

FILE - Elon Musk jumps on the stage as Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump speaks at a campaign rally at the Butler Farm Show, Saturday, Oct. 5, 2024, in Butler, Pa. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File)

FILE - Staff members of The Associated Press Television Network work in master control at the Washington bureau of The Associated Press in Washington, Nov. 8, 2016, as returns come in during election night. (AP Photo/Jon Elswick)

FILE - Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump listens as Elon Musk speaks during a campaign rally at the Butler Farm Show, Saturday, Oct. 5, 2024, in Butler, Pa. (AP Photo/Julia Demaree Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Voting machines fill the floor for early voting at State Farm Arena, Oct. 12, 2020, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, File)

FILE - The North Carolina State Capitol in Raleigh, N.C., on July 24, 2013. (AP Photo/Gerry Broome, File)

FILE - The Capitol in Washington, is seen at sunrise, Wednesday, Sept. 13, 2023. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

FILE - Josh Riley, New York's 19th Congressional District Democratic candidate, speaks to supporters gathered at his election party in Binghamton, N.Y., Nov. 8, 2022. (AP Photo/Heather Ainsworth, File)

FILE - Residents place their signatures on a petition in support of a ballot initiative to end Missouri's near-total ban on abortion during Missourians for Constitutionals Freedom kick-off petition drive, Feb. 6, 2024, in Kansas City, Mo. (AP Photo/Ed Zurga, File)

FILE - Bartender Sam Schilke watches election results on television at a bar and grill Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020, in Portland, Ore. (AP Photo/Paula Bronstein, File)

This 2020 image provided by ABC15 Arizona shows ABC15 Arizona data journalist Garrett Archer. (ABC15 Arizona via AP)

FILE - Seth Golding, right, and Braydon Galliers, left, a bipartisan team of ballot fulfillment coordinators, empty an absentee voter drop-off ballot box on Election Day outside of the Franklin County Board of Elections in Columbus, Ohio, Tuesday, Nov. 7, 2023. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster, File)

FILE - Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows attends Democratic Gov. Janet Mill's State of the State address Jan. 30, 2024, at the State House in Augusta, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, File)

FILE - Jotaka Eaddy of the NAACP speaks during a panel discussion on black turnout for midterm elections and voter suppression during the NAACP annual convention Tuesday, July 22, 2014, in Las Vegas. (AP Photo/John Locher, File)

A ballot drop box is seen, Wednesday, March 6, 2024, in Sherwood, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

FILE - Maine Democratic Secretary of State Shenna Bellows speaks with an aide in her office after the House voted down an attempt to impeach her on Tuesday, Jan. 9, 2024, in Augusta, Maine. (AP Photo/David Sharp, File)

FILE - Cari-Ann Burgess, interim registrar of voters for Washoe County, Nev., walks through the office Sept. 20, 2024, in Reno, Nev. (AP Photo/John Locher, File)

FILE - Secretary of State Shenna Bellows attends the inauguration of Gov. Janet Mills, Wednesday, Jan. 4, 2023, at the Civic Center in Augusta, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, File)

FILE - Jay Begay moves his flock of sheep on horseback near his home on Sunday, Oct. 30, 2022, in the Navajo Nation in Arizona. (AP Photo/John Locher, File)

FILE - A person drops off their vote-by-mail ballot at a dropbox in Pioneer Square during primary voting on Tuesday, May 21, 2024, in Portland, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane, File)

FILE - A person puts their ballot in a drop box at a library in Seattle's White Center neighborhood on Oct. 27, 2020. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren, File)

FILE - First lady Jill Biden speaks during a live radio address to the Navajo Nation at the Window Rock Navajo Tribal Park & Veterans Memorial in Window Rock, Ariz., on Thursday, April 22, 2021.(Mandel Ngan/Pool via AP, File)

FILE - North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, center left, watches a robotics team at Nashville Elementary School in Nashville, N.C., direct its vehicle in the school library, Tuesday, Jan. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Gary D. Robertson, File)

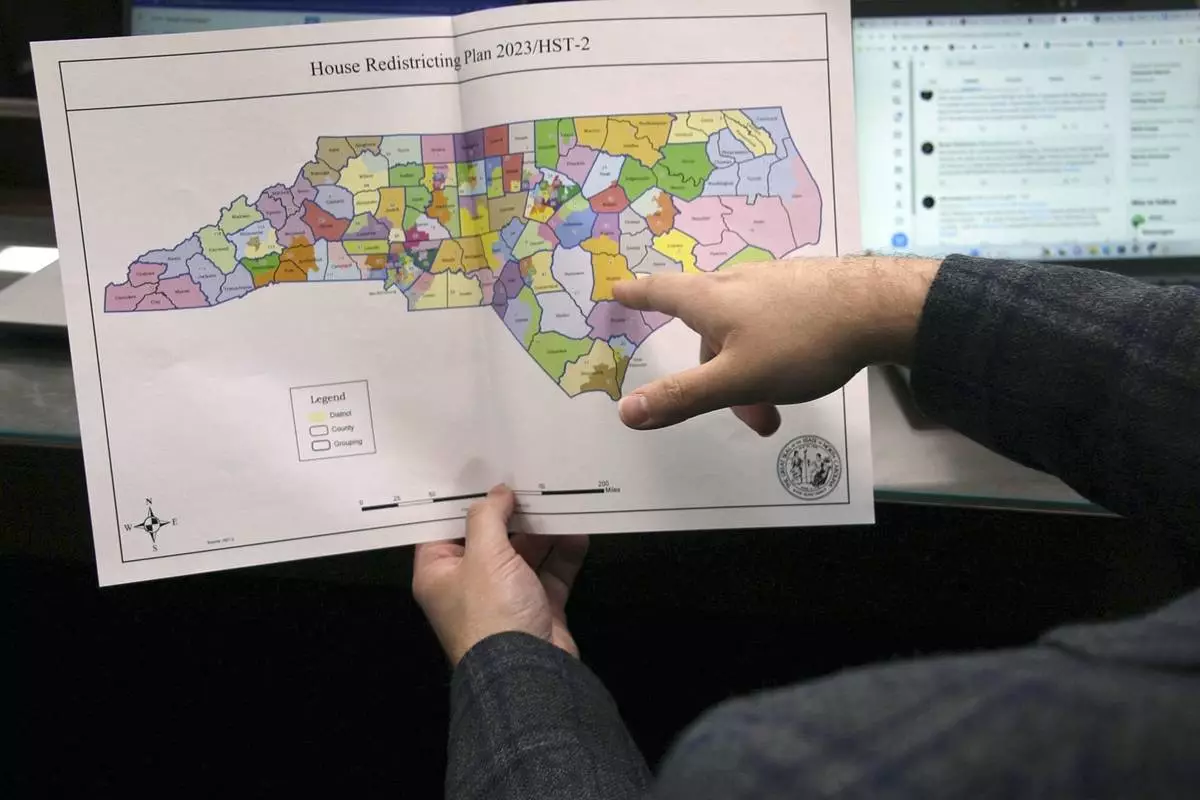

FILE - The North Carolina state House reviews copies of a map proposal for new state House districts during a committee hearing at the Legislative Office Building in Raleigh, N.C., Thursday, Oct. 19, 2023. (AP Photo/Hannah Schoenbaum, File)

FILE - Buu Nygren announces his win for the Navajo Nation president as he reads tabulated votes from chapter houses across the reservation at his campaign's watch party at the Navajo Nation fairgrounds in Window Rock, Ariz., on Tuesday, Nov. 8, 2022. (AP Photo/William C. Weaver IV, File)

FILE - The Apache County Superior Courthouse shown here Thursday, Oct. 22, 2020, in St. Johns, Ariz. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin, File)

FILE - Miss Navajo Nation pageant contestant Amy Begaye, left, prepares a sheep with help from Kashlynn Benally during a sheep-butchering contest, Monday, Sept. 4, 2023, on the Navajo Nation in Window Rock, Ariz. (AP Photo/John Locher, File)

FILE - A person in American flag poses for pictures during the Republican National Convention Thursday, July 18, 2024, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Julia Nikhinson, File)

FILE - Republican presidential candidate former President Donald Trump, center, stands on stage with Melania Trump and other members of his family during the Republican National Convention, July 18, 2024, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Julia Nikhinson, File)

FILE - A voter casts her ballot, April 2, 2024, in Milwaukee, Wis. (AP Photo/Morry Gash, File)

FILE - Police officers ride bikes around outside of the Republican National Convention area July 18, 2024, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, File)

FILE - Buildings stand in the Milwaukee skyline, Sept. 6, 2022, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Morry Gash, File)

FILE - This July 8, 2021, photograph shows a hiker en route to Lake Bonnie Rose, one of many scenic hiking options on Adak Island, Alaska. (Nicole Evatt via AP, File)

Mary Nelson, of Mead, Wash., near Spokane, Wash., poses for a photo at her home on Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024. Nelson is holding a printout of a radio station website news story that says she is thought to be the last person in the U.S. to cast a vote in the 2012 presidential election when she voted for Mitt Romney just before the polls closed in the remote village of Adak, Alaska. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

FILE - This is a general view of the Army's task force Williwaw camp on Alaska's Adak Island, shown Feb. 3, 1947, with Mount Moffett in background. The Quonset huts were dug in as protection against the winds. (AP Photo/Joseph D. Jamieson, File)

FILE - Absentee ballots are seen during a count at the Wisconsin Center for the midterm election on Nov. 8, 2022, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Morry Gash, File)

FILE - Votes are tallied during a manual recount of ballots in the City Council District 5 race between incumbent Mykey Arthrell and challenger Grant Miller, Nov. 17, 2022, in Tulsa, Okla. (Mike Simons/Tulsa World via AP, File)

FILE - Mildred James of Sanders, Ariz., shows off her "I Voted" sticker as she waits for results of the Navajo Nation presidential primary election to be revealed in Window Rock, Ariz., Aug. 28, 2018. (AP Photo/Cayla Nimmo, File)