WASHINGTON (AP) — On Election Day, some voting lines will likely be long and some precincts may run out of ballots. An election office website could go down temporarily and ballot-counting machines will jam. Or people who help run elections might just act like the humans they are, forgetting their key to a local polling place so it has to open later than scheduled.

These kinds of glitches have occurred throughout the history of U.S. elections. Yet election workers across America have consistently pulled off presidential elections and accurately tallied the results — and there's no reason to believe this year will be any different.

Elections are a foundation of democracy. They also are human exercises that, despite all the laws and rules governing how they should run, can sometimes appear to be messy. They're conducted by election officials and volunteers in thousands of jurisdictions across the United States, from tiny townships to sprawling urban counties with more voters than some states have people.

It's a uniquely American system that, despite its imperfections, reliably produces certified outcomes that stand up to scrutiny. That's true even in an era of misinformation and hyperpartisanship.

“Things will go wrong,” said Jen Easterly, the director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency.

None of these will mean the election is tainted or rigged or is being stolen. But Easterly said election offices need to be transparent about the hiccups so they can get ahead of misinformation and attempts to exploit routine problems as a way to undermine confidence in the election results.

"At the end of the day, we need to recognize things will go wrong. They always do," Easterly said. “It will really come down to how state and local election officials communicate about those things going wrong.”

It wasn't that long ago when American voters accepted the results, even if their preferred presidential candidate lost.

Even in 2000, when 104 million votes came down to a 5-to-4 Supreme Court decision that effectively made Republican George W. Bush the president, his opponent, Democrat Al Gore, quickly conceded. The republic moved on peacefully.

Times have changed dramatically since then.

The internet, false claims and a voting public susceptible to conspiratorial theories about widespread voter fraud have changed that. Trust in the system is low, particularly among Republican voters whose perceptions have been shaped by a steady drumbeat of lies about the 2020 election by Donald Trump, the former president who is the Republican nominee on the Nov. 5 ballot.

At his campaign rallies, Trump continues to claim that the only way he can lose is if the other side rigs the election. In fact, it would be virtually impossible for anyone to rig a U.S. presidential race given the decentralized nature of the country's elections, which are run by thousands of municipal or county voting jurisdictions.

What is more likely are simple mistakes and technical mishaps that occur during every election.

“When elections are very close and you have to look under the hood, sometimes you find some problems. Almost always those problems are the result of human error, incompetence — not malfeasance,” said Rick Hasen, an election law expert and professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Both voter fraud and election administrator fraud is currently very rare in the United States. When it does happen, it’s not that hard to catch because of the safeguards in the system.”

Distrust in elections is real and has serious consequences. Lies about the 2020 election being rigged were a catalyst for the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

This has come despite Trump and his allies losing dozens of court cases aimed at reversing his loss to Democrat Joe Biden. Even a commission Trump created while president to investigate the 2016 election in hopes of identifying widespread voter fraud found none. Special police units established by a few Republican governors came up similarly empty-handed when they searched for widespread fraud during the 2022 midterm elections.

In addition to the court cases, Trump’s own attorney general and reviews, recounts and audits in the presidential battleground states found no evidence of widespread fraud and affirmed Biden’s victory.

That hasn't mattered.

As late as 2023, a sizable portion of Republicans believed Biden was not the legitimately elected, and election conspiracy theories have taken root in Republican-leaning communities.

It would be incorrect to say there is never any fraud associated with elections. But in the 2020 election, an Associated Press investigation in the battleground states where Trump disputed his loss found an amount too small to alter the election. In most cases, it was individuals acting alone, not as part of a grand conspiracy to throw the election.

“The story of the last few decades is that voting systems in the United States are very secure," said Robert Lieberman, a political science professor at Johns Hopkins University.

Basic mistakes, whether human or technical.

In Jackson, Mississippi, a ballot problem was blamed on inexperience and lack of training. In Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, inexperience was again the culprit when polling places ran out of ballots.

Sometimes the envelopes used to return the mailed ballots can create problems. The Pennsylvania Department of State recently announced on X that because of high humidity levels in much of the state, “some voters are finding that their mail-in ballots have the return envelope already sealed." It advised voters to contact their local election office for next steps.

Paper was the culprit in a Maricopa County, Arizona, in 2022 when the ballot printers had problems and caused large backups in voter lines.

One of the major concerns heading into the 2024 presidential election is the high turnover in election offices across the country, in particular in some of the presidential battlegrounds, said Edward B. Foley, a law professor who leads Ohio State University’s election law program.

Before the 2022 midterms, for example, 10 of Nevada's 17 counties had turnover among their clerk or registration positions, which oversee voting.

Threats and harassment from those who believe election conspiracy theories have fueled the attrition. Despite all the training election workers receive, there’s no substitute for the experience of going through a major election cycle.

Many of those who have left had years and even decades of experience. In some cases, they have been replaced by people with little or no experience, and who at times have peddled conspiracy theories.

“If you're looking for something to watch out for and be concerned about," Foley said, "that is one place.”

Associated Press writers Christina A. Cassidy and Ali Swenson contributed to this report.

Read more about how U.S. elections work at Explaining Election 2024, a series from The Associated Press aimed at helping make sense of the American democracy. The AP receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Jen Easterly speaks to The Associated Press in Washington, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

FILE - People wait to vote in-person at Reed High School in Sparks, Nev., prior to polls closing on Nov. 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Scott Sonner, File)

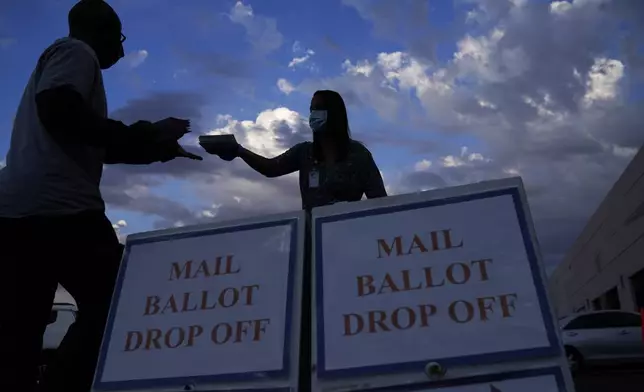

FILE - A county worker collects a mail-in ballots in a drive-thru mail-in ballot drop off area at the Clark County Election Department, Monday, Nov. 2, 2020, in Las Vegas. (AP Photo/John Locher, File)

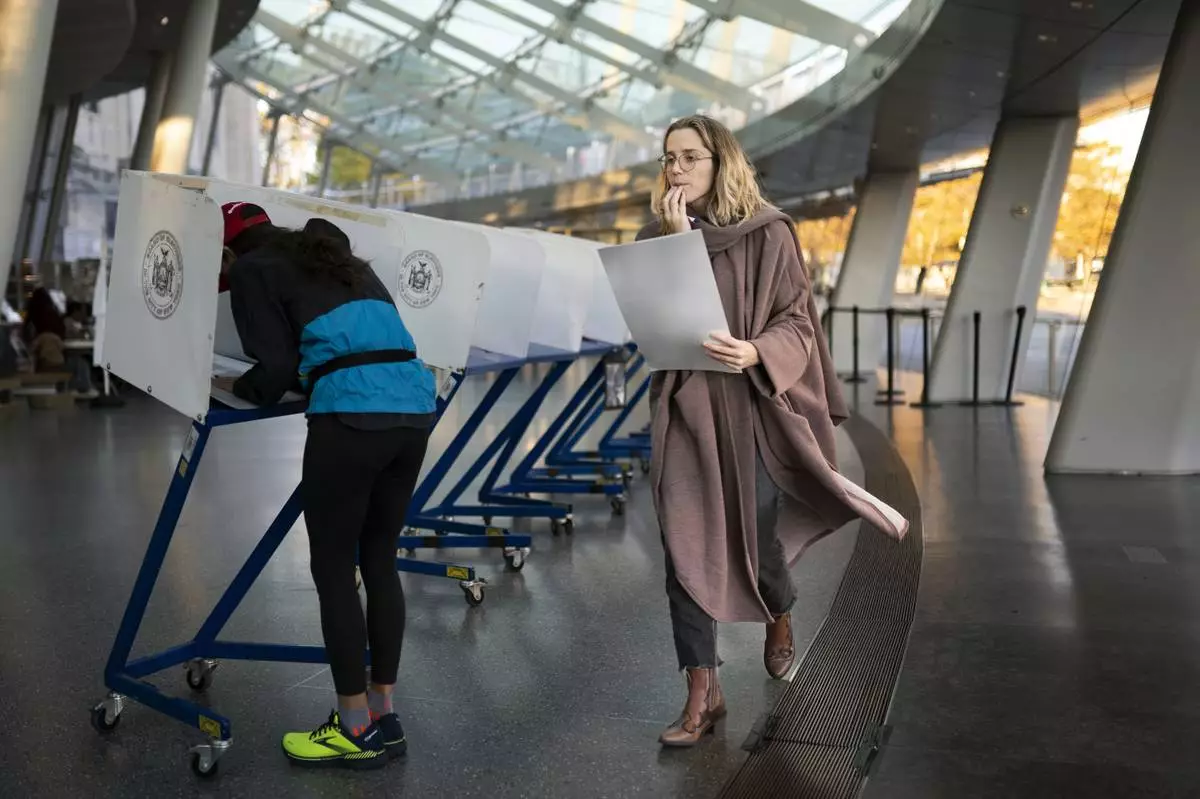

FILE - A voter moves to cast her ballot at an electronic counting machine at a polling site at the Brooklyn Museum, Nov. 8, 2022, in the Brooklyn borough of New York. ( AP Photo/John Minchillo, File)

FILE - Director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Jen Easterly speaks to The Associated Press in Washington, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

FILE "- I Voted Early" stickers sit in a bucket by the ballot box at the City of Minneapolis early voting center, Thursday, Sept. 19, 2024, in St. Paul, Minn. (AP Photo/Adam Bettcher, File)

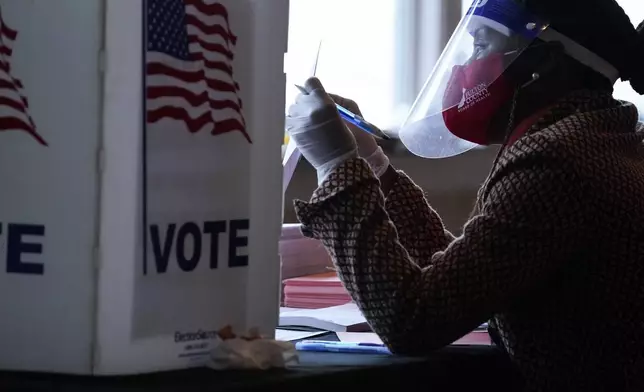

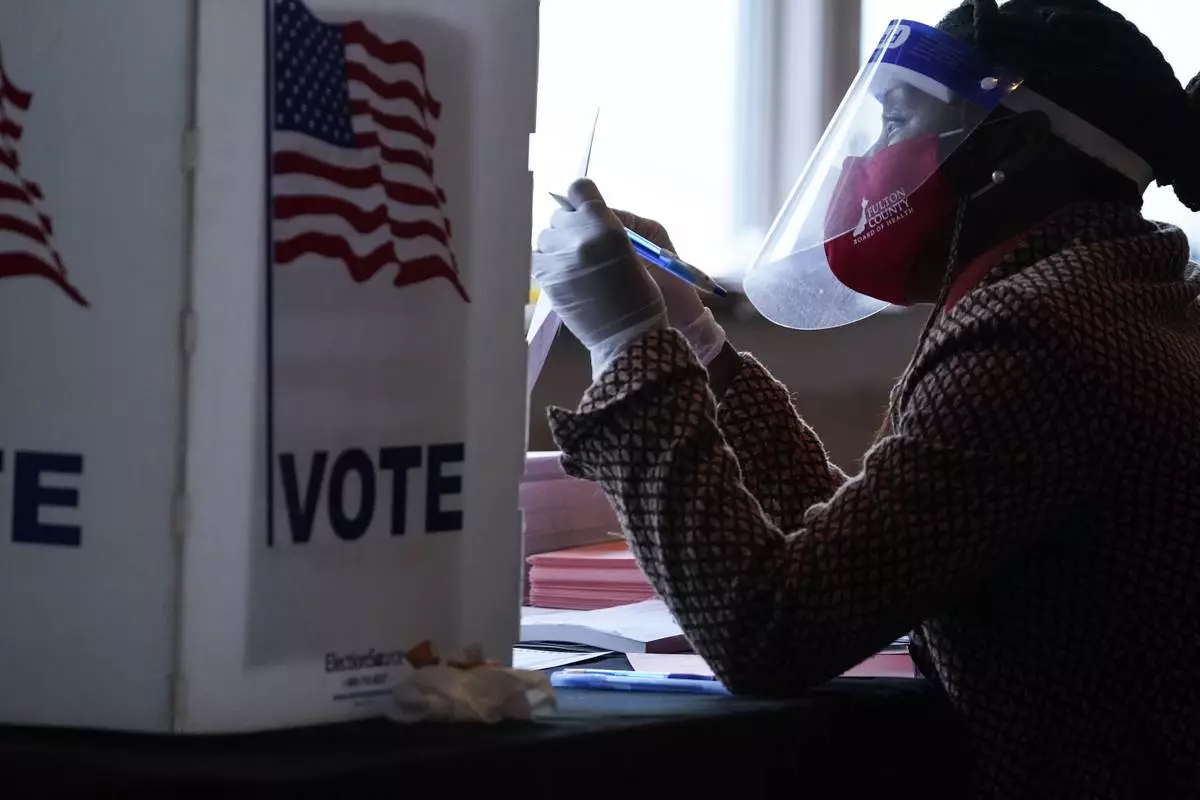

FILE - A poll worker talks to a voter before they vote on a paper ballot on Election Day in Atlanta on Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson, File)

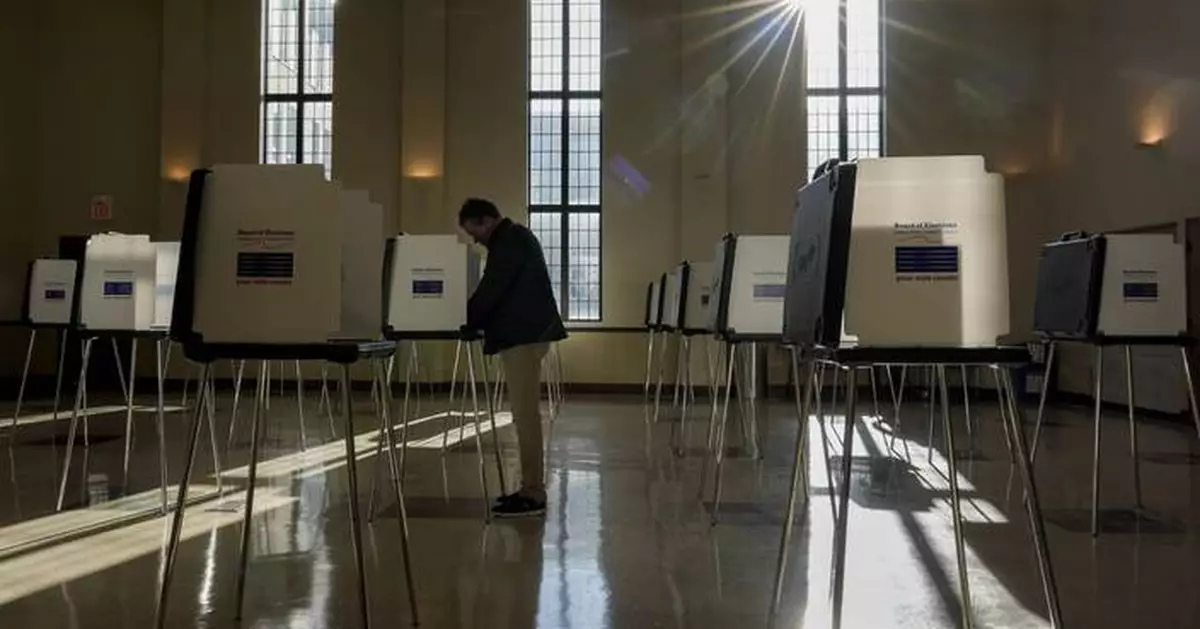

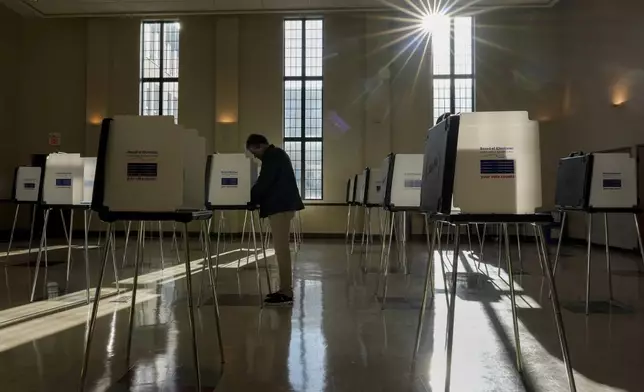

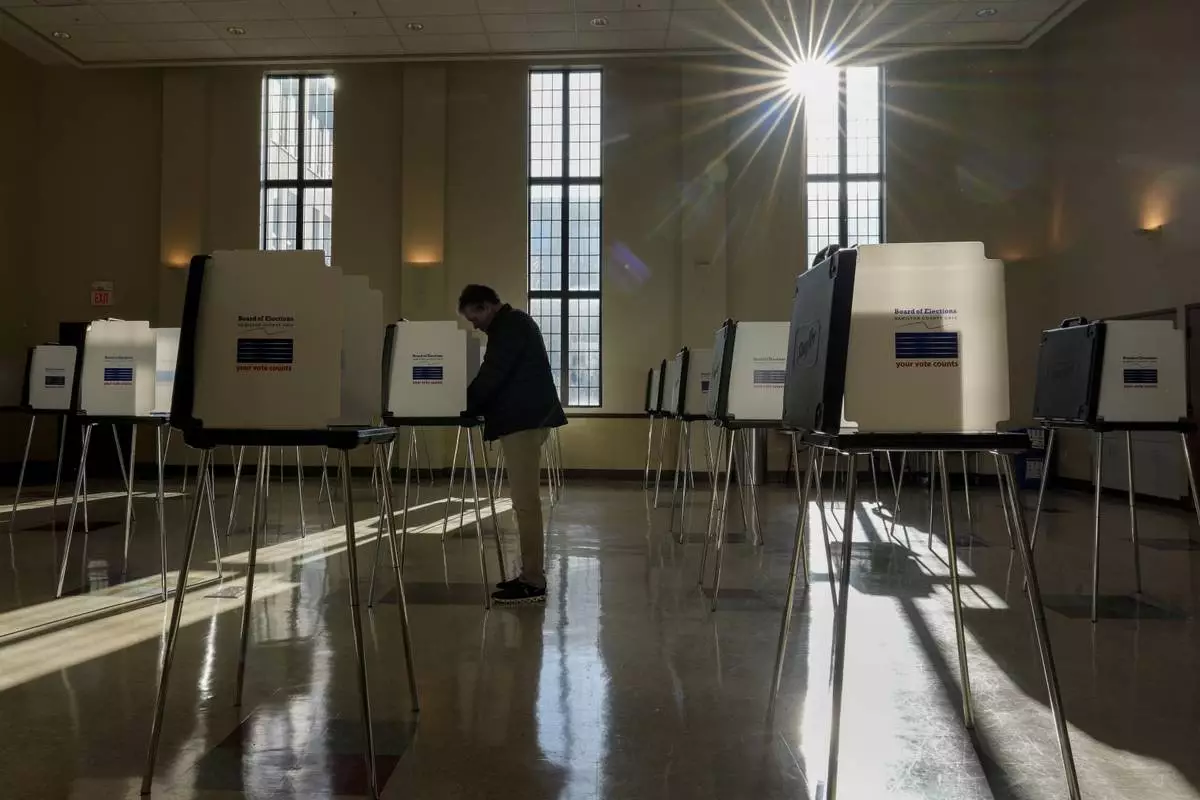

FILE - A voter fills out their Ohio primary election ballot at a polling location in Knox Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati, Ohio, on Tuesday, March 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster, File)