He's been tough on Russia, led the charge to put prize money in the pockets of athletes and pushed for a definitive but much-derided resolution in the longstanding debate over transgender athletes.

Some might say Sebastian Coe's penchant for going against the grain makes him more of a thorn in the side of the International Olympic Committee than an ideal candidate to become its next president.

The 68-year-old gold-medal runner who led the 2012 London Olympic Committee and, now, the organization that governs global track and field, isn't so sure of that.

He’s among seven IOC members running to replace Thomas Bach next year. Coe is banking on the idea that the IOC's other 110 members might be ready to have a bigger say in what the candidate sees as a necessary “reset in the movement around sports.” He’s positioning himself as the right person for the job due to his record of getting things done — both popular (successful London Games, gender equity at the top of World Athletics) and difficult (a lot of the rest).

In his first interview since announcing his candidacy, Coe spoke with The Associated Press about his past, his guiding principle that “if you get it right for the athletes, you’re going to get 80% of it right,” and his belief that his sometimes contrarian ways won’t necessarily be a dealbreaker for him in the election in March.

“A lot of the criticism I’ve gotten from people in the sporting world, which I found a little depressing, was the assumption that good politics is about basically playing safe and ... not leaving the herd and sometimes taking risks,” Coe said. “And bad politics is doing just that.”

If all that is true, then the former member of the British Parliament will admit to being bad at politics. But it’s also a strategy that has defined his journey through sports.

There is a sense that the cards are stacked against Coe in the race for IOC president.

Last month, the committee released a clarifying document about its rules for potential candidates. Among its points were that IOC members can't serve past the age of 74. That, and other directives in the letter, appear aimed at Coe, who would age out before the end of the president's traditional eight-year term.

Most of the issues could be overcome if the other members want him badly enough.

Then, there's the issue of whether Bach, who has a heavy hand in guiding the IOC, supports him. How much that matters is a great unknown; the election of the president, unlike most issues undertaken by the IOC, is done by secret ballot.

Coe speaks warmly of the outgoing president and considers him a friend. When Coe gave the first speech by an athlete to the Olympic Congress back in 1981 (he pressed to get four minutes at the lectern when the leaders were only offering two) Bach, just winding down a successful fencing career at the time, helped him write it.

To this day, when they see each other, Coe cheekily calls Bach “Professor” and Bach, in return, calls Coe “Shakespeare.”

That they diverge on major points in the direction of what both consider their life's work does not, in Coe's mind, make them enemies.

“You just have to accept that not everyone's going to see the world in the same way,” said Coe, who won gold medals in the 1,500-meter race at the 1980 Moscow Olympics and the 1984 Los Angeles Games. “Your job is to try to persuade them that that's a direction you'd like them to come. You then put structures in place where they see the benefits of what we're trying to achieve.”

Coe has received great credit — or vicious blame — for many of the policies he's spearheaded since he became president of World Athletics in 2015.

He pushed to establish the Athletics Integrity Unit to take anti-doping matters out of the hands of track's leaders and have them resolved independently.

Along with that tough-on-doping stance came what amounted to a zero-tolerance plan for the Russians, who were held out of major international track meets because of the country's long-running doping program, which also involved Coe's predecessor at World Athletics, Lamine Diack.

At about the time the doping issues were being resolved, World Athletics kept Russia on the sideline because of the war in Ukraine, a move Coe portrayed as a one of fairness, not politics. The rest of the Olympic world has been much more resistant about taking hard lines against Russia.

Coe's insistence on bringing clarity to the issue of eligibility for transgender athletes and those born with differences of sexual development, known as DSD, has received more criticism than praise. Coe has portrayed it as a move to “protect the integrity of women's sport” in track and field.

“I think, in fact, I know, he's on the wrong side of history with this,” said Jules Boykoff, a political scientist and longtime observer of the Olympic movement, who called the transgender decision one of Coe's few, but very notable, missteps in sports leadership. “But maybe he'll be able to be persuaded.”

Coe's most recent foray into norm-bending came when World Athletics announced it was awarding $50,000 to track and field's Olympic gold medalists in Paris.

“I said to my team, this is not going to be unalloyed joy," he said. “The athletes are going to love it ... but I knew there would be some backlash.”

The backlash came largely from sports leaders who felt the money should be used for other purposes — like growing sports in poor countries — or from those whose own sports don't have the same resources as track.

Some of that criticism came from the very same pool of IOC members Coe might need to win what could be the last big contest of his life.

But maybe not the toughest.

Coe grew up in northern England in the steel and coal town of Sheffield. As he tells the story, if your name was Sebastian and you lived in Sheffield in the 1970s, you had to learn to fight or run, and so, the rest is history.

The upbringing gave him a first-hand view of the plight of athletes, even at the elite level, who he says still, to this day, have a “financial safety net that is paper thin.”

Some six decades later, he sees similarities between his run for IOC president and his first big political race, which landed him in the British Parliament in 1992.

He was never a shoo-in. His decision to compete at the boycotted Moscow Olympics in 1980 when many British sat out was not universally popular. Neither was his stringent stance against Apartheid — he refused to race in South Africa in the 1980s.

His own conservative party toyed with having him removed from the ticket.

“I have a lot of Indian heritage in my family,” said Coe, in explaining his feelings about Apartheid. “I'd rather face the wrath of Margaret Thatcher than the wrath of my mother sitting around the dining room table saying to me ‘Are you demented?’

“I have always tended to stand my ground on things I truly believe in,” Coe said.

In 2003, British Prime Minister Tony Blair, whose own popularity helped end Coe's stay in Parliament, asked Coe to head up London's bid for the 2012 Olympics.

Coe said yes. The London Games have been widely viewed as the rare success story plucked out of a chaotic generation of games held in China, Russia and Brazil that brought with them the unavoidable feeling that the Olympics were an industry in decline.

If nothing else, the recent success in Paris restored a feeling that the Games are no longer in need of saving.

As he embarks on his final campaign, Coe agrees with that. He also envisions the success as “a massive opportunity” — to find new sources of revenue, to enhance the viewing experience and to keep a young generation of sports fans invested in Summer and Winter Olympic events that come once every four years.

He sees his fellow IOC members as more than mere rubber-stampers, but titans of industry, banking, entertainment and politics who can make a difference in the future.

“The red carpet is rolled out in front of us but we have to walk down it," he said. "We have to make some tough decisions. That's what the membership has to be involved in. You can't operate on the basis of, 'This is what I'm doing, this is what I'm saying.' This has to be a joint journey.”

AP Summer Olympics: https://apnews.com/hub/2024-paris-olympic-games

FILE - IAAF President Sebastian Coe attends a press conference ahead of the Doha IAAF Diamond League in Doha, Qatar, May 2, 2019. (AP Photo/Kamran Jebreili, File)

FILE - In this Aug. 11, 1984, file photo, Britain's Sebastian Coe holds up the Union Jack after winning the men's 1,500-meter race at the Summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Dieter Endlicher, File)

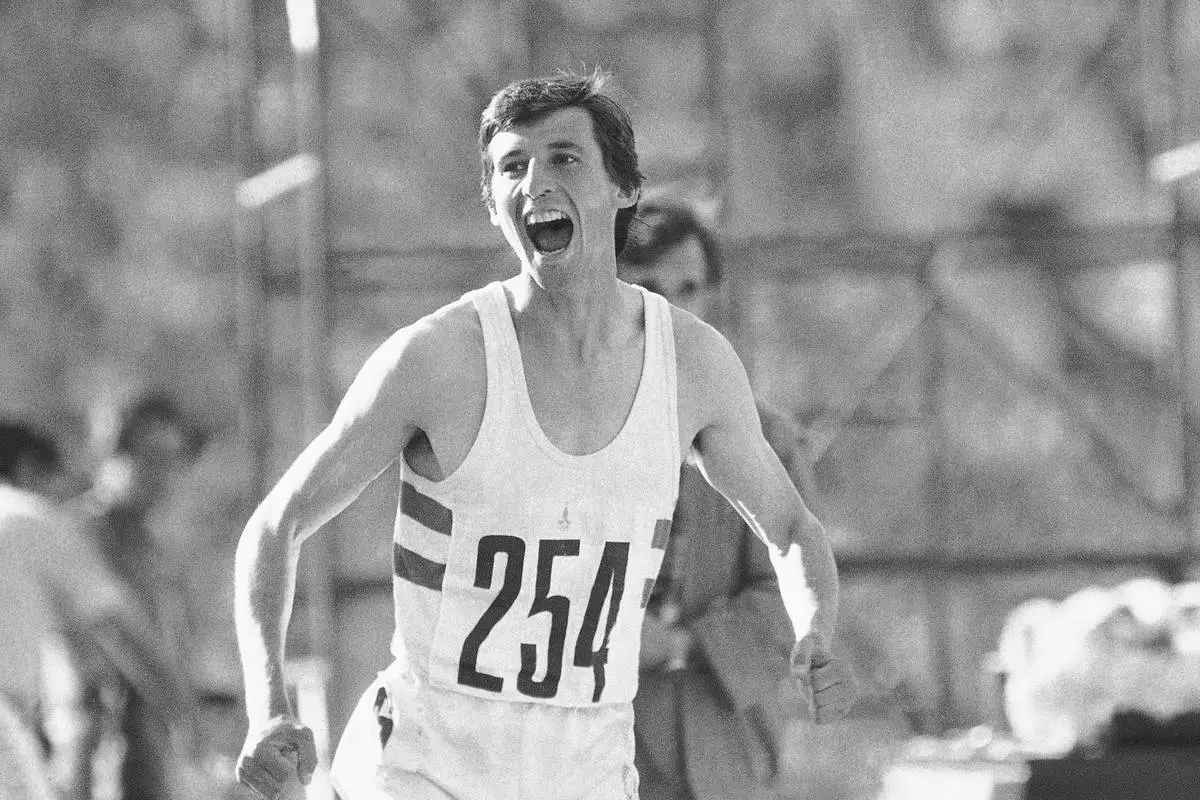

FILE - Britain's Sebastian Coe celebrates his victorious finish in the men's 1,500-meter race on Friday, August 1, 1980 at the Moscow Olympics in Moscow. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - World Athletics President Sebastian Coe holds a press conference at the conclusion of the World Athletics meeting at the Italian National Olympic Committee, headquarters in Rome, Nov. 30, 2022. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)