PHILADELPHIA (AP) — Fifty years ago, Philadelphia prison officials ended a medical testing program that had allowed an Ivy League researcher to conduct human testing on incarcerated people, many of them Black, for decades. Now, survivors of the program and their descendants want reparations.

Thousands of people at Holmesburg Prison were exposed to painful skin tests, anesthesia-free surgery, harmful radiation and mind-altering drugs for research on everything from hair dye, detergent and other household goods to chemical warfare agents and dioxins. In exchange, they might receive $1-a-day in pocket change they used to buy commissary items or try to make bail.

Click to Gallery

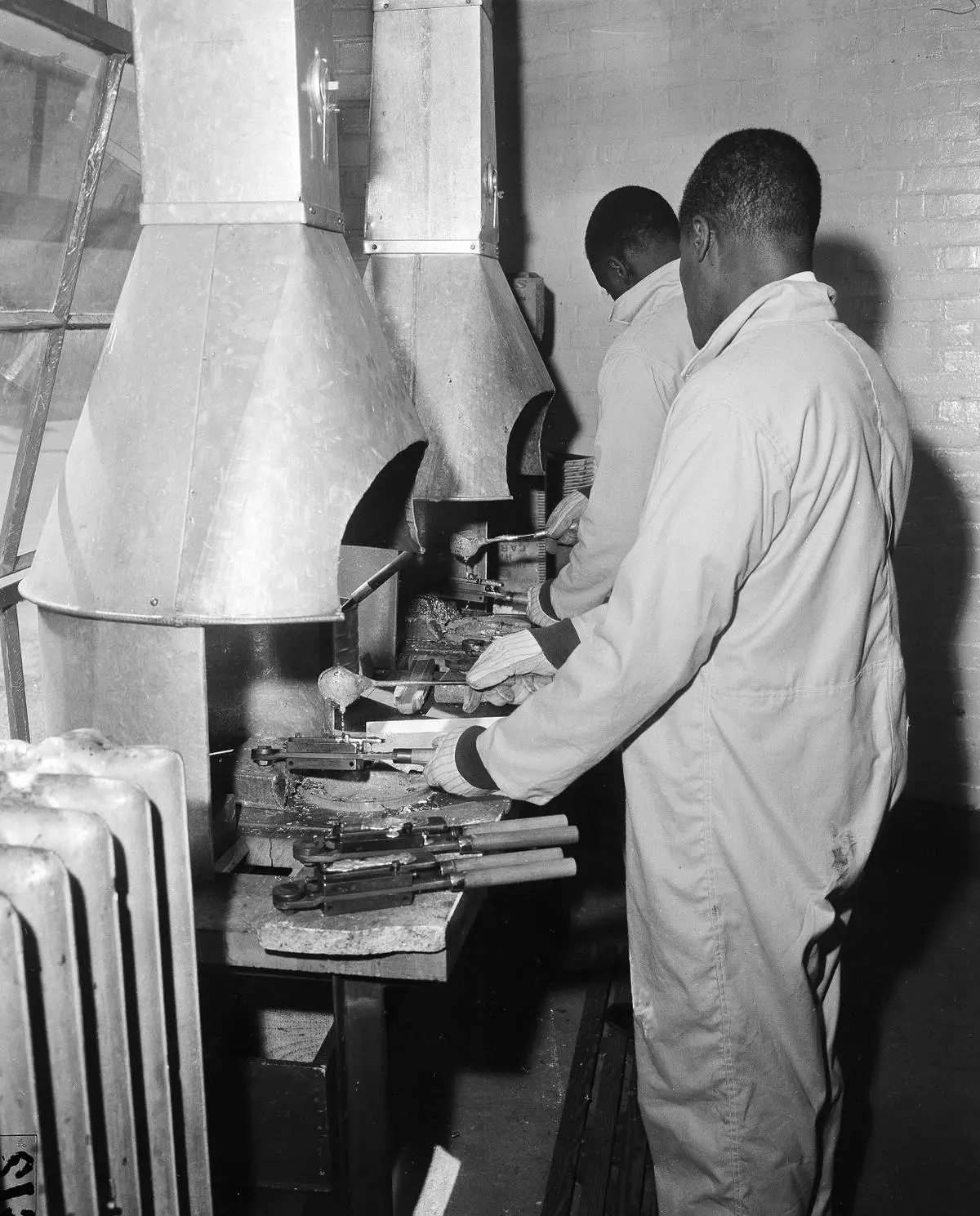

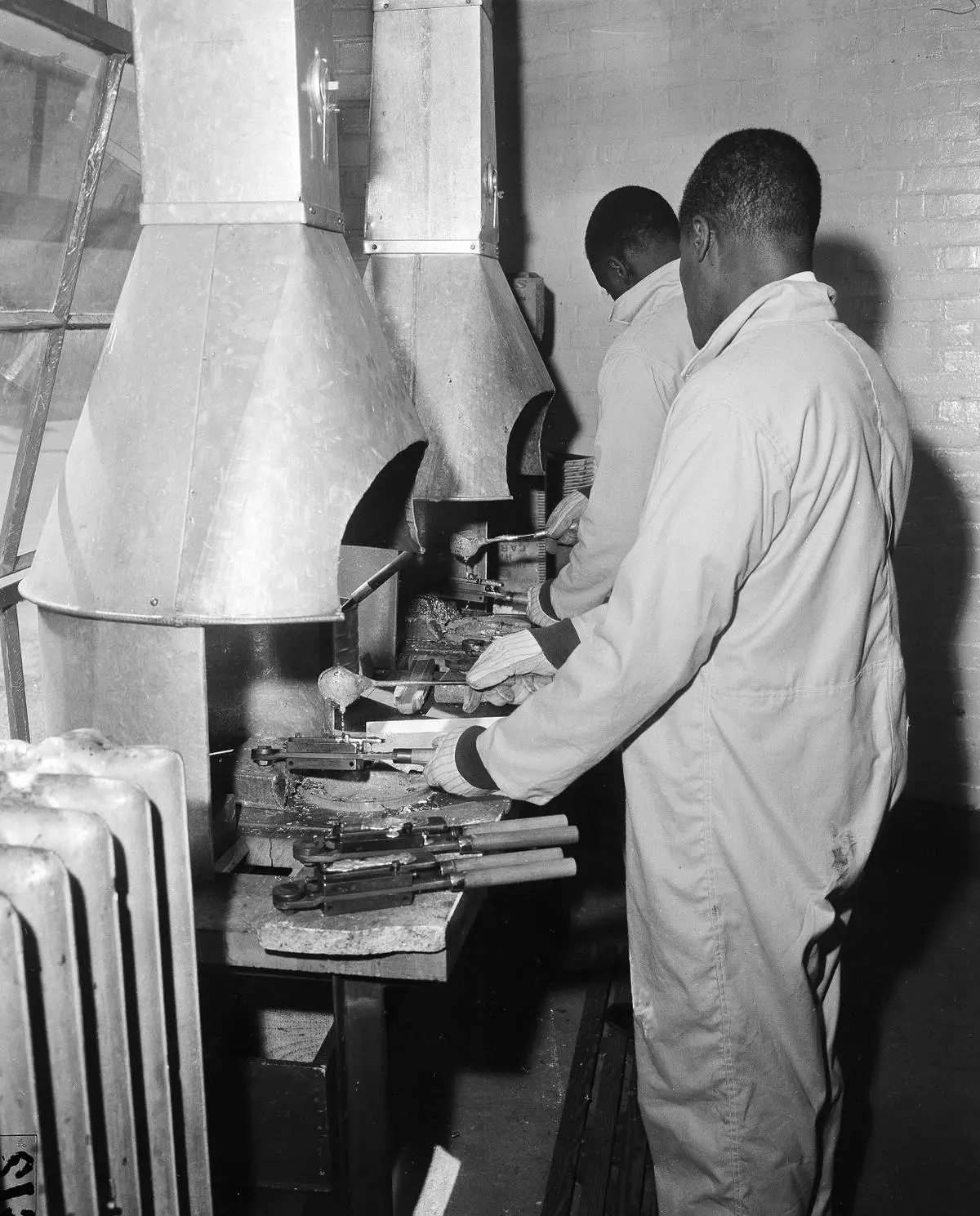

FILE - People incarcerated at the maximum security Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia, turn out bullets for police revolvers, April 16, 1957. (AP Photo/Bill Ingraham, File)

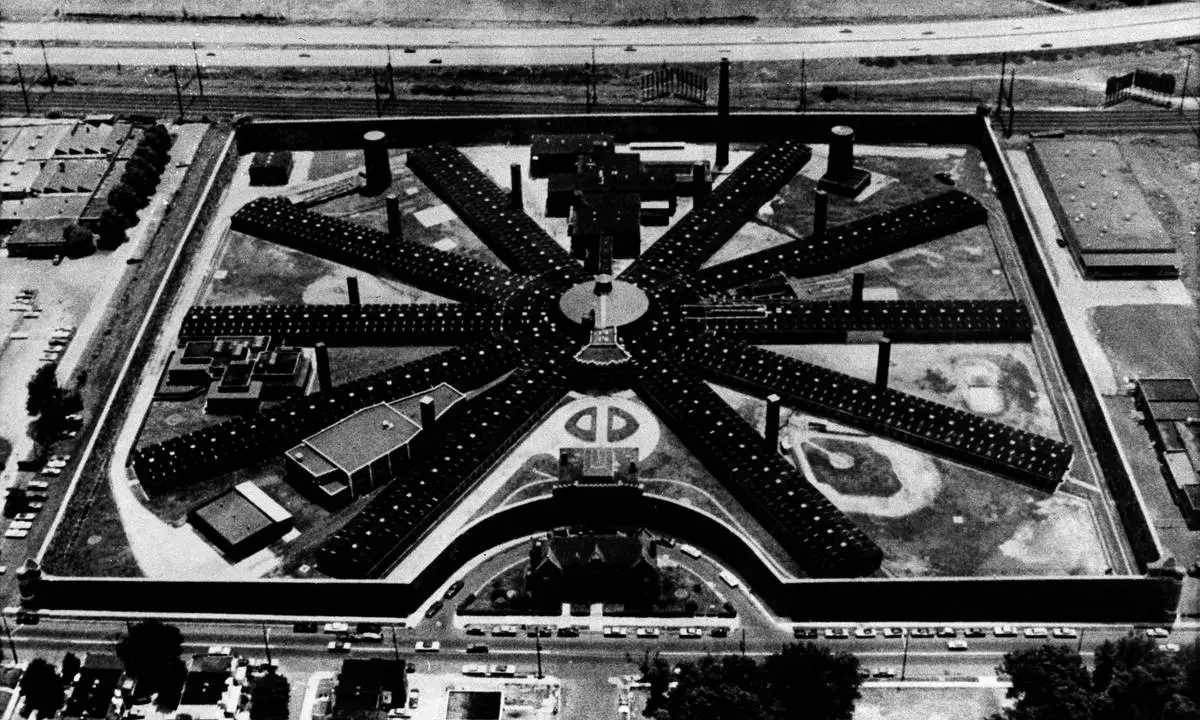

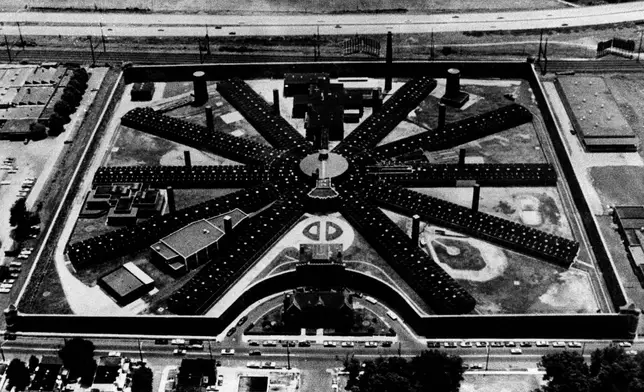

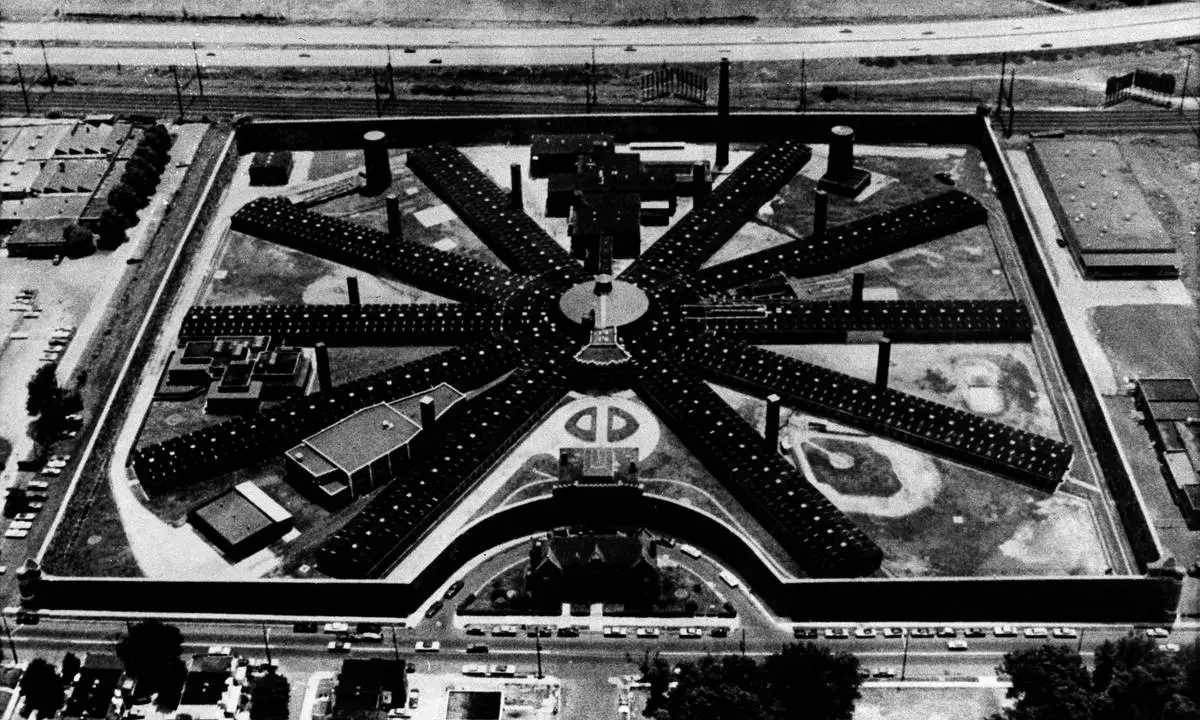

FILE - Holmesburg Prison, in the northeast section of Philadelphia, 1970. (AP Photo/Bill Achatz, File)

FILE - Edward Anthony speaks of his time at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia and the tests in which he participated while incarcerated there, Oct. 24, 2007. (Michael Bryant/The Philadelphia Inquirer via AP, File)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to other former inmates on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to media at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, right, is embraced by Adrianne Jones-Alston, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

“We were fertile ground for them people,” said Herbert Rice, a retired city worker from Philadelphia who said he has had lifelong psychiatric problems after taking an unknown drug at Holmesburg in the late 1960s that caused him to hallucinate. “It was just like dangling a carrot in front of a rabbit.”

The city and the University of Pennsylvania have issued formal apologies in recent years. Lawsuits have been mostly unsuccessful, except for a few small settlements. On Wednesday, families at a Penn law school event are set to seek reparations from the school and pharmaceutical companies that they say benefited from the Cold War-era research.

A University of Pennsylvania spokesperson said the school had no comment on the push for reparations.

The testing was led by Albert M. Kligman, a University of Pennsylvania dermatologist with research ties to the Army, the CIA and the pharmaceutical industry, according to author Allen Hornblum, who ran an adult literacy program at Holmesburg in the 1970s and saw the effects firsthand.

Medical testing in prisons was pervasive in the 1960s, with radiation studies conducted on people incarcerated in Washington and Oregon, cancer studies in Ohio and flash burn studies in Virginia, Hornblum said.

Human testing was also conducted on children in institutions, hospital patients and other vulnerable populations in much of the 20th century. The tide turned in the early 1970s, when outrage over the Tuskegee Syphilis Study — in which the U.S. government let Black men go untreated for syphilis to study the disease's impact — sparked an evolution in medical ethics, Hornblum said. Kligman defended his work until his death in 2010.

He is credited with being the first dermatologist to show a link between sun exposure and wrinkles. He patented Retin-A, a vitamin A derivative known generically as tretinoin, as an acne treatment in 1967 and received a new patent in 1986 after discovering the drug’s wrinkle-fighting ability.

“Retin-A was discovered and made at Holmesburg Prison,” Rice said. “They made millions and millions of dollars off the skin on our backs.”

In a 1966 interview with The Philadelphia Inquirer, Kligman described his first visit to Holmesburg with excitement, saying, “All I saw before me were acres of skin.”

Hornblum said there may be some parallels in the case of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose descendants settled a lawsuit last year against a biomedical company that reproduced her cervical cells in 1951 without her permission. The resulting HeLa cells have gone on to become a cornerstone of modern medicine.

Rice, after serving about three years for burglary, later got his GED and built a 30-year career with the city recreation department, rising to a supervisory position. But he also did three stints in psychiatric hospitals, watched his marriage disintegrate and lost touch with his children for a time. As he nears his 80th birthday, he still takes lithium and can’t sleep without medication.

He said he would accept reparations but that they wouldn't change much for him.

"No amount of money can replace what was done to me, what was done to my children and wife. This thing was generational,” Rice said, later adding, “There’s nothing that can be done to make it right. I’m going to be like this the rest of my life.”

FILE - People incarcerated at the maximum security Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia, turn out bullets for police revolvers, April 16, 1957. (AP Photo/Bill Ingraham, File)

FILE - Holmesburg Prison, in the northeast section of Philadelphia, 1970. (AP Photo/Bill Achatz, File)

FILE - Edward Anthony speaks of his time at Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia and the tests in which he participated while incarcerated there, Oct. 24, 2007. (Michael Bryant/The Philadelphia Inquirer via AP, File)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to other former inmates on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, speaks to media at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, right, is embraced by Adrianne Jones-Alston, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

Herbert Rice, 79, poses for a photo at the University of Pennsylvania, on Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2024, in Philadelphia. Rice is one of many Black men who took part in prison medical testing from 1951 to 1974 at Philadelphia city prisons. (AP Photo/Laurence Kesterson)

CHEYENNE, Wyo. (AP) — A famous grizzly bear beloved for decades by countless tourists, biologists and professional wildlife photographers in Grand Teton National Park is dead after being struck by a vehicle in western Wyoming.

Grizzly No. 399 died Tuesday night on a highway in Snake River Canyon south of Jackson, park officials said in a statement Wednesday, adding the driver was unhurt. A yearling cub was with the grizzly when she was struck and though not believed to have been hurt, its whereabouts were unknown, according to the statement.

The circumstances of the crash were unclear. Grand Teton and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officials said they had no further information to release about it.

At 28 years old, No. 399 was the oldest known reproducing female grizzly in the Yellowstone ecosystem. Each spring, wildlife enthusiasts eagerly awaited her emergence from her den to see how many cubs she had birthed over the winter — then quickly shared the news online.

Named for the identity tag affixed by researchers to her ear, the grizzly amazed watchers by continuing to reproduce into old age. Unlike many grizzly bears, she was often seen near roads in Grand Teton, drawing crowds and traffic jams.

Scientists speculate such behavior kept male grizzlies at a distance so they would not be a threat to her cubs. Some believe male grizzlies kill cubs to bring the mother into heat.

The bear had 18 known cubs in eight litters over the years, including a litter of four in 2020. She stood around 7 feet (2.1 meters) tall and weighed about 400 pounds (180 kilograms).

Hundreds of visitors at times would gather at a wide meadow to see her in the evenings, recalled Grand Teton bear biologist Justin Schwabedissen.

Some youngsters "just thought that was just the coolest thing in the world to see a bear out there, cubs wrestling in the wildflowers,” Schwabedissen said.

Another time he met a just-retired Midwest factory worker whose dream was to see a bear in the wild.

“She was in tears that night from being able to have an opportunity to see her,” Schwabedissen said.

News of the bear's death spread quickly on a Facebook page that tracks the grizzly and other wildlife in Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks. By late Wednesday more than 2,000 people posted comments calling the bear a “magnificent queen,” an “icon” and an “incredible ambassador for her species.”

They were heartbroken and devastated by her death, calling it a tragic loss.

The momma bear had fans all over the world, said tour guides Jack and Gina Bayles, who run the Team 399 Facebook page and planned to visit the site where she was killed.

“You might say she was the accidental ambassador of the species,” Jack Bayles said. “My single biggest concern is that people are now gonna lose interest in bears.”

The grizzly lived through a time of strife over her species in the region, as state officials have sought to gain management control over grizzlies from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, saying the bears' numbers have rebounded past the point of being at risk.

Conservation groups have objected, saying climate change imperils some of the bears' key food sources including whitebark pine cones.

Some 50,000 grizzlies once roamed the western United States. But outside Alaska they are now confined to pockets in the Yellowstone region and northern Rockies. They dwindled in the Yellowstone region to just over 100 animals by 1975, when they were first protected as a threatened species.

The region encompassing Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks and surrounding areas in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho is now home to some 1,000 grizzlies. They remain federally protected but in an ongoing tug-of-war between political and court decisions have bounced off and back on the threatened list twice in recent years.

Government biologists say the population is healthy and officials from the three Yellowstone states continue to seek their removal from federal protection.

On average, about three grizzlies annually in the region are killed in vehicle collisions, with 51 killed since 2009, according to data collected by researchers and released by the park. No. 399 was the second grizzly killed in the region by a vehicle this year.

“Wildlife vehicle collisions and conflict are unfortunate. We are thankful the driver is okay and understand the community is saddened to hear that grizzly bear 399 has died,” Wyoming Game and Fish Department Director Angi Bruce said in the statement.

Amy Beth Hanson in Helena, Montana, contributed to this report.

FILE - Grizzly bear No. 399 and her four cubs cross a road as Cindy Campbell stops traffic in Jackson Hole, Wyo., on Nov. 17, 2020. (Ryan Dorgan/Jackson Hole News & Guide via AP, File)

FILE - Grizzly bear 399 and her four cubs feed on a deer carcass on Nov. 17, 2020, in southern Jackson Hole. (Ryan Dorgan/Jackson Hole News & Guide via AP, File)