NORMAN, Okla. (AP) — President Joe Biden said he will formally apologize on Friday for the country’s role in forcing Indigenous children for over 150 years into boarding schools, where many were physically, emotionally and sexually abused, and more than 950 died.

“I’m doing something I should have done a long time ago: To make a formal apology to the Indian nations for the way we treated their children for so many years,” Biden said Thursday as he left the White House for Arizona.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland launched an investigation into the boarding school system shortly after she became the first Native American to lead the agency, and she will join Biden during his first diplomatic visit to a tribal nation as president as he delivers a speech Friday at the Gila River Indian Community outside Phoenix.

“I would never have guessed in a million years that something like this would happen,” Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna in New Mexico, told The Associated Press. “It’s a big deal to me. I’m sure it will be a big deal to all of Indian Country.”

The investigation she launched found that at least 18,000 children — some as young as 4 — were taken from their parents and forced to attend schools that sought to assimilate them into white society while federal and state authorities sought to dispossess tribal nations of their land.

The investigation documented 973 deaths — while acknowledging the figure is likely higher — and 74 gravesites associated with the more than 500 schools.

No president has ever formally apologized for the forced removal of these children — an element of genocide as defined by the United Nations — or the U.S. government's actions to decimate Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian peoples.

The Interior Department conducted listening sessions and gathered the testimony of survivors. One of the recommendations of the final report was an acknowledgement of, and apology for, the boarding school era. Haaland said she took that to Biden, who agreed that it was necessary.

“In making this apology, the President acknowledges that we as a people who love our country must remember and teach our full history, even when it is painful. And we must learn from that history so that it is never repeated," the White House said in a statement.

The forced assimilation policy launched by Congress in 1819 as an effort to “civilize” Native Americans ended in 1978 after the passage of a wide-ranging law, the Indian Child Welfare Act, which was primarily focused on giving tribes a say in who adopted their children.

The visit by Biden and Haaland to the Gila River Indian Community comes as Vice President Kamala Harris' campaign spends hundreds of millions of dollars on ads targeting Native American voters in battleground states including Arizona and North Carolina.

“It will be one of the high points of my entire life,” Haaland said of Biden's apology Friday.

It’s unclear what action, if any, will follow the apology. The Interior Department is still working with tribal nations to repatriate the remains of children on federal lands. Some tribes are still at odds with the U.S. Army, which has refused to follow federal law regulating the return of Native American remains when it comes to those still buried at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

“President Biden’s apology is a profound moment for Native people across this country,” Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said in a statement to the AP.

“Our children were made to live in a world that erased their identities, their culture and upended their spoken language,” Hoskin said in his statement. “Oklahoma was home to 87 boarding schools in which thousands of our Cherokee children attended. Still today, nearly every Cherokee Nation citizen somehow feels the impact.”

Friday’s apology could lead to further progress for tribal nations still pushing for continued action from the federal government, said Melissa Nobles, chancellor of MIT and author of "The Politics of Official Apologies."

“These things have value because it validates the experiences of the survivors and acknowledges they’ve been seen,” Nobles said.

The U.S. government has offered apologies for other historic injustices, including to Japanese families it imprisoned during World War II. President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act in 1988 to compensate tens of thousands of people sent to internment camps during the war.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton signed a law apologizing to Native Hawaiians for the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy a century earlier.

The House and Senate passed resolutions in 2008 and 2009 apologizing for slavery and Jim Crow segregation. But the gestures did not create pathways to reparations for Black Americans.

In Canada, a country with a similar history of subjugating First Nations and forcing their children into boarding schools for assimilation, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper made a formal apology in 2008. There was also a truth and reconciliation process, and later a plan to inject billions of dollars into communities devastated by the government’s policies.

Pope Francis issued a historic apology in 2022 for the Catholic Church’s cooperation with Canada’s policy of Indigenous residential schools, saying the forced assimilation of Native people into Christian society destroyed their cultures, severed families and marginalized generations.

“I humbly beg forgiveness for the evil committed by so many Christians against the Indigenous peoples,” Francis said.

In 2008, Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd formally apologized to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for his government’s past policies of assimilation, including the forced removal of children. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern made a similar concession in 2022.

Hoskin said he is grateful to both Biden and Haaland for leading the effort to reckon with the country’s role in a dark chapter for Indigenous peoples. But he emphasized that the apology is just “an important step, which must be followed by continued action.”

FILE - Elders from the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in southeastern Montana listen to speakers during a session for survivors of government-sponsored Native American boarding schools, in Bozeman, Mont., Nov. 5, 2023. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)

FILE - Russell Eagle Bear, with the Rosebud Sioux Reservation Tribal Council, talks to U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland during a meeting about Native American boarding schools at Sinte Gleska University in Mission, S.D., on Oct. 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown, File)

Israeli airstrikes on the Gaza Strip overnight killed at least 20 people, Palestinian medics said Monday.

One of the strikes killed eight people including two kids in a tent camp in the Muwasi area, which Israel designated a humanitarian safe zone but has repeatedly targeted. The casualties were reported by Nasser Hospital in the southern city of Khan Younis, which received the bodies.

The Israeli military says it only strikes militants, accusing them of operating among civilians. It said late Sunday that it had targeted a Hamas militant in the humanitarian zone.

The war began when Hamas-led militants attacked southern Israel in October 2023, killing some 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and taking around 250 hostage. Around 100 captives are still inside Gaza, at least a third of whom Israel believes are dead.

Israel’s air and ground offensive has killed more than 45,200 Palestinians, according to Gaza’s Health Ministry. The ministry says women and children make up more than half the dead but does not distinguish between civilians and combatants in its tally. The military says it has killed over 17,000 militants, without providing evidence.

Here’s the latest:

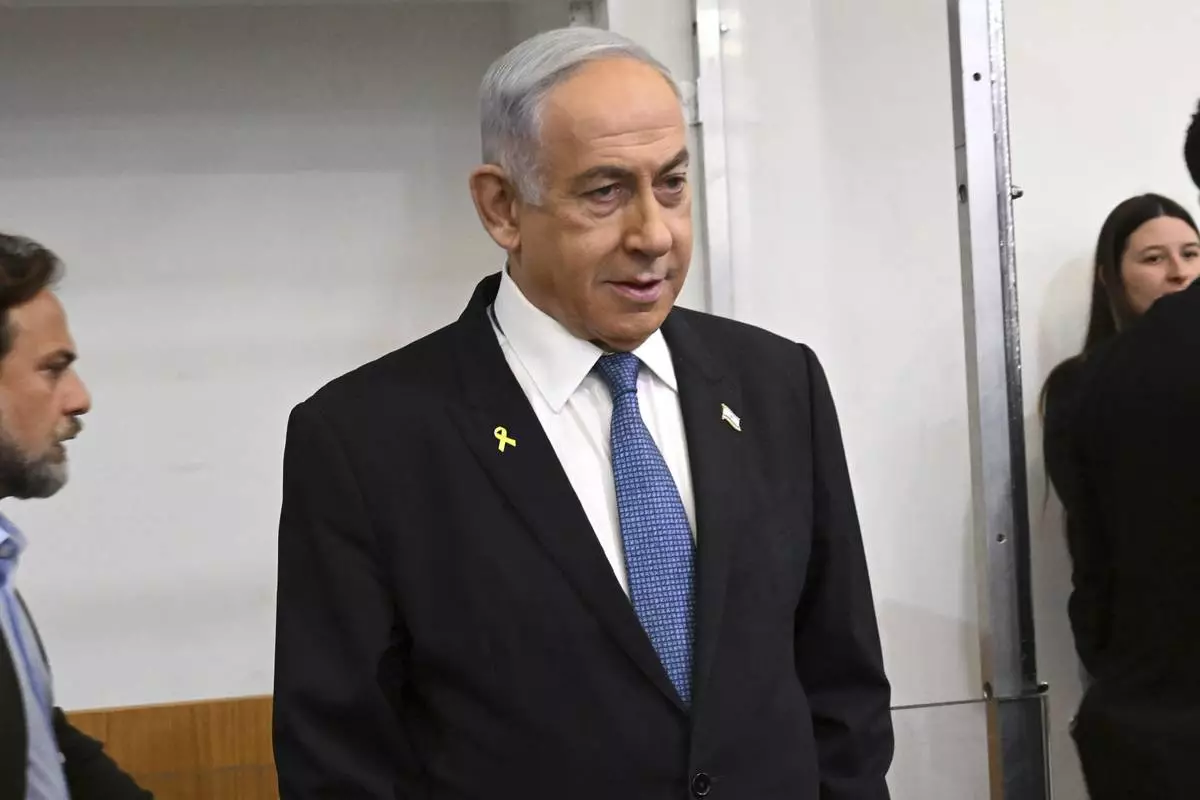

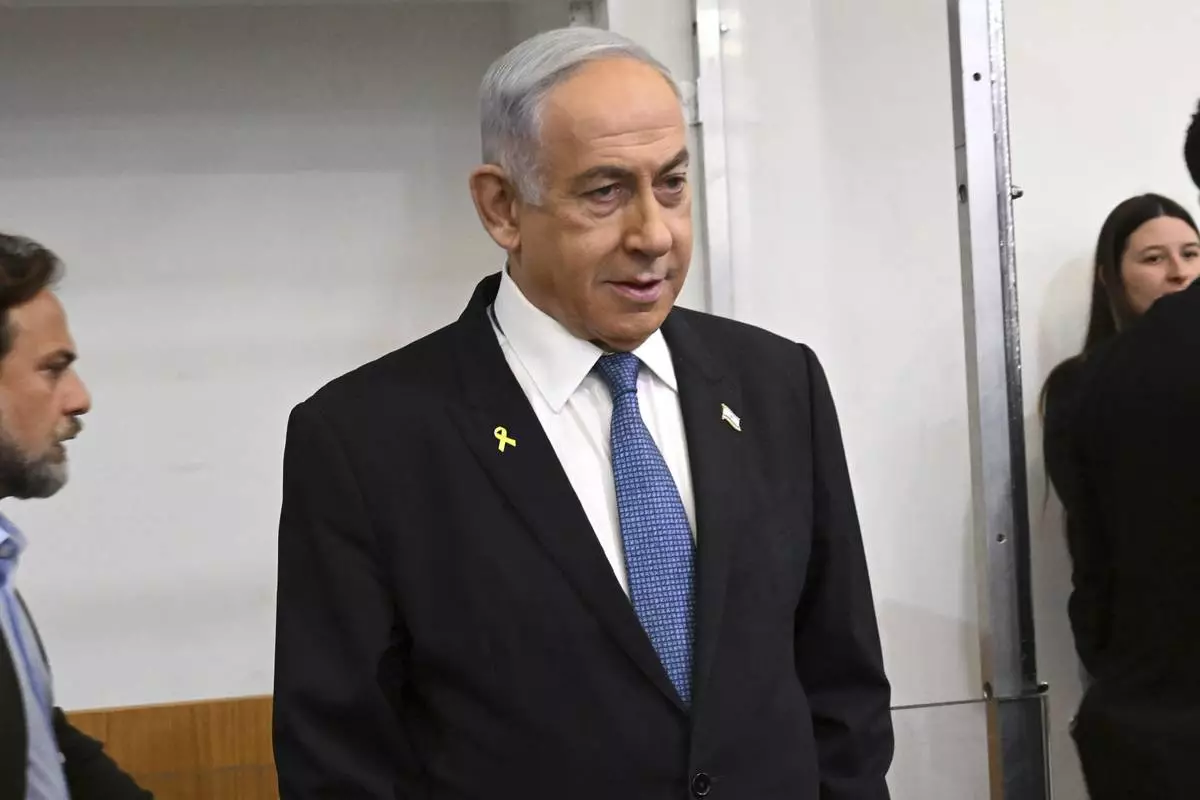

JERUSALEM — Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Monday there is “some progress” in efforts to reach a hostage and ceasefire deal in Gaza, although he added he could not give a time frame for a possible agreement.

Of the roughly 250 people who were taken hostage in the Hamas-led raid on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023 that sparked the war, around 100 are still inside the Gaza Strip, at least a third of whom are believed to be dead.

Speaking in the Knesset, Netanyahu said “we are taking significant actions through all channels to return our loved ones. I would like to tell you cautiously that there is some progress.”

Netanyahu said he could not reveal details of what was being done to secure the return of hostages. He said the main reasons for the progress were the death of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar and Israel’s military actions against Iran-backed Hezbollah militants who had been firing rockets into Israel from neighboring Lebanon in support of Hamas.

“Hamas hoped that Iran and Hezbollah would come to its aid but they are busy licking the wounds from the blows we inflicted on them,” he said, adding that Israel was also putting “relentless military pressure” on Hamas in Gaza.

“There is progress. I don’t know how long it will take,” Netanyahu said.

JERUSALEM — Israel's military said Monday it intercepted a drone launched from Yemen before it entered Israeli territory, days after a long-range rocket attack by Yemen's Houthi rebels hit Tel Aviv, injuring 16 people from shattered glass.

The military said no air raid warning sirens were sounded Monday. Israel says the Iran-backed Houthis have fired more than 200 missiles and UAVs, or unmanned aerial vehicles, during the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza.

The Houthis have also been attacking shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden — attacks they say won’t stop until there is a ceasefire in Gaza.

The attacks on shipping and Israel are taking place despite U.S. and European warships patrolling the area. On Saturday night and early Sunday, the U.S. conducted airstrikes on Yemen. Last week, Israel launched its own airstrikes on Yemen, killing at least nine people, and a Houthi missile damaged a school in Israel.

DAMASCUS, Syria — A Qatari delegation visited the Syrian capital on Monday for the first time in more than a decade and met with the country's top insurgent commander, who said strategic cooperation between Damascus and Doha will begin soon.

Qatar, along with Turkey, has long backed the rebels who now control Damascus, and the two countries are looking to protect their interests in Syria now that former President Bashar Assad has been overthrown.

The Qatari delegation was headed by the minister of state for foreign affairs, Mohammed al-Khulaifi, who met with Ahmad al-Sharaa, leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, the insurgent group that overthrew Assad on Dec. 8.

Al-Sharaa was quoted as saying by Syrian media that they have invited the emir of Qatar to visit Damascus adding that relations will return to normal soon. Al-Sharaa said Qatar will back Syria during the transitional period and the two countries will soon start “wide strategic cooperation.”

Al-Sharaa also met Monday with Jordan’s Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi as well as a Saudi official.

Unlike Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Jordan had relations with Assad’s government until he was removed from power.

JENIN, West Bank — The Palestinian Authority says a second member of its security forces has been killed in the West Bank town of Jenin during clashes with Palestinian militants.

Brig. Gen. Anwar Rajab, the spokesman for PA security forces, said 1st Sgt. Mehran Qadoos was killed on Monday by “outlaws” in the volatile northern town, where the security forces launched a rare crackdown earlier this month. A member of security forces also was killed on Sunday.

An Associated Press reporter in Jenin heard heavy gunfire and explosions, apparently from a battle between the security forces and Palestinian militants. There was no sign of Israeli forces in the area.

Militant groups had earlier called for a general strike across the territory, accusing the security forces of trying to disarm them in support of Israel’s half-century occupation of the territory.

The Western-backed Palestinian Authority is internationally recognized but deeply unpopular among Palestinians, in part because it cooperates with Israel on security matters. Israel accuses the authority of incitement and of failing to act against armed groups.

The Palestinian Authority exercises limited authority in population centers in the West Bank. Israel captured the territory in the 1967 Mideast War, and the Palestinians want it to form the main part of their future state.

Israel’s current government is opposed to Palestinian statehood and says it will maintain open-ended security control over the territory. Violence has soared in the West Bank following Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023 attack out of Gaza, which ignited the war there.

JENIN, West Bank — Palestinians in the volatile northern West Bank town of Jenin are observing a general strike called by militant groups to protest a rare crackdown by Palestinian security forces.

An Associated Press reporter in Jenin heard gunfire and explosions, apparently from clashes between militants and Palestinian security forces. It was not immediately clear if anyone was killed or wounded. There was no sign of Israeli troops in the area.

Shops were closed in the city on Monday, the day after militants killed a member of the Palestinian security forces and wounded two others.

Militant groups called for a general strike across the territory, accusing the security forces of trying to disarm them in support of Israel’s half-century occupation of the territory.

The Western-backed Palestinian Authority is internationally recognized but deeply unpopular among Palestinians, in part because it cooperates with Israel on security matters. Israel accuses the authority of incitement and of failing to act against armed groups.

The Palestinian Authority blamed Sunday’s attack on “outlaws.” It says it is committed to maintaining law and order but will not police the occupation.

The Palestinian Authority exercises limited authority in population centers in the West Bank. Israel captured the territory in the 1967 Mideast War, and the Palestinians want it to form the main part of their future state.

Israel’s current government is opposed to Palestinian statehood and says it will maintain open-ended security control over the territory. Violence has soared in the West Bank following Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023 attack out of Gaza, which ignited the war there.

BEIRUT — Lebanon’s caretaker prime minister has begun a tour of military positions in the country’s south, almost a month after a ceasefire deal that ended the war between Israel and the Hezbollah group that battered the country.

Najib Mikati on Monday was on his first visit to the southern frontlines, where Lebanese soldiers under the U.S.-brokered deal are expected to gradually deploy, with Hezbollah militants and Israeli troops both expected to withdraw by the end of next month.

Mikati’s tour comes after the Lebanese government expressed its frustration over ongoing Israeli strikes and overflights in the country.

“We have many tasks ahead of us, the most important being the enemy's (Israel's) withdrawal from all the lands it encroached on during its recent aggression,” he said after meeting with army chief Joseph Aoun in a Lebanese military barracks in the southeastern town of Marjayoun. “Then the army can carry out its tasks in full.”

The Lebanese military for years has relied on financial aid to stay functional, primarily from the United States and other Western countries. Lebanon’s cash-strapped government is hoping that the war’s end and ceasefire deal will bring about more funding to increase the military’s capacity to deploy in the south, where Hezbollah’s armed units were notably present.

Though they were not active combatants, the Lebanese military said that dozens of its soldiers were killed in Israeli strikes on their premises or patrolling convoys in the south. The Israeli army acknowledged some of these attacks.

Smoke rises as Palestinian security forces mount a major raid against militants in the Jenin refugee camp in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Majdi Mohammed)

Palestinians sit in front of closed shops during a general strike called as Palestinian security forces mount a major raid against militants in the Jenin refugee camp in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Majdi Mohammed)

Journalists take cover from gunfire as Palestinian security forces mount a major raid against militants in the Jenin refugee camp in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Majdi Mohammed)

Officers from the Palestinian Authority clutch their guns as Palestinian security forces mount a major raid against militants in the Jenin refugee camp in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Majdi Mohammed)

Armored Palestinian security vehicles are seen on the road as Palestinian forces mount a major raid against militants in the Jenin refugee camp in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Majdi Mohammed)

Israel's security officers check a damaged car at the site of an attack in east Jerusalem neighborhood of Pisgat Zeev, Israel, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu attends the fifth day of testimony in his trial on corruption charges at the district court in Tel Aviv, Israel, on Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (Debbie Hill/Pool Photo via AP)

Weapons and other equipment seized by the Israeli military during its ground invasion of southern Lebanon are displayed, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Ohad Zwigenberg)

Georges Elia decorates a Christmas tree inside St. George Melkite Catholic Church, that was destroyed by Israeli airstrike, in the town of Dardghaya in southern Lebanon, Sunday, Dec. 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar)

A worshipper prays in the Church of the Nativity where Christians believe Jesus Christ was born, ahead of Christmas in the West Bank city of Bethlehem, Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Palestinians pray over the bodies of the victims of an Israeli strike on a home late Saturday before the funeral outside the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah Sunday, Dec. 22, 2024. At least eight people were killed according to the hospital which received the bodies.(AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)

Relatives and neighbors, two of them holding guns, walk during the funeral procession of a victim of an Israeli strike on a home late Saturday that killed at least eight people, in Deir al-Balah, central Gaza Strip, Sunday, Dec. 22, 2024. Some families in Gaza are armed to protect their homes from thieves in the camps.(AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana)