LAVEEN VILLAGE, Ariz. (AP) — President Joe Biden did something Friday that no other sitting U.S. president has: He apologized for the systemic abuse of generations of Indigenous children endured in boarding schools at the hands of the federal government.

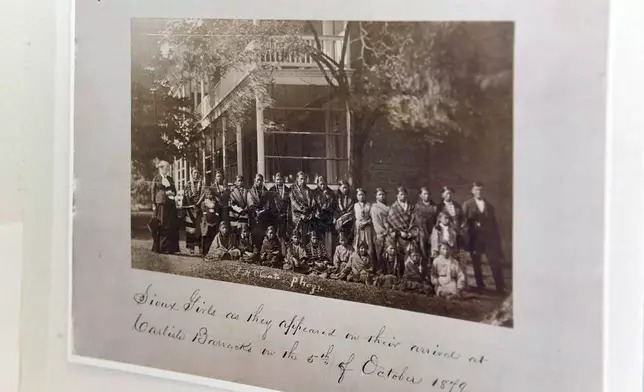

For 150 years the U.S. removed Indigenous children from their homes and sent them away to the schools, where they were stripped of their cultures, histories and religions and beaten for speaking their languages.

“We should be ashamed,” Biden said to a crowd of Indigenous people gathered at the Gila River Indian Community outside of Phoenix, including tribal leaders, survivors and their families. Biden called the government-mandated system that began in 1819 “one of the most horrific chapters in American history,” while acknowledging the decades of abuse inflicted upon children and widespread devastation left behind.

For many Native Americans, the long-awaited apology was a welcome acknowledgment of the government’s longstanding culpability. Now, they say, words must be followed up by action.

Bill Hall, 71, of Seattle, was 9 when he was taken from his Tlingit community in Alaska and forced to attend a boarding school, where he endured years of physical and sexual abuse that lead to many more years of shame. When he first heard that Biden was going to apologize, he wasn’t sure he would be able to accept it.

“But, as I was watching, tears began to flow from my eyes,” Hall said. “Yes, I accept his apology. Now, what can we do next?”

Rosalie Whirlwind Soldier, a 79-year-old citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said she felt “a tingle in my heart” and was glad the historical wrong was being acknowledged. Still, she remains saddened by the irreversible harms done to her people.

Whirlwind Soldier suffered severe mistreatment at a school in South Dakota that left her with a lifelong, painful limp. The Catholic-run, government-subsidized facility took away her faith and tried to stamp out her Lakota identity by cutting off her long braids, she said.

“Sorry is not enough. Nothing is enough when you damage a human being,” she said. “A whole generation of people and our future was destroyed for us.”

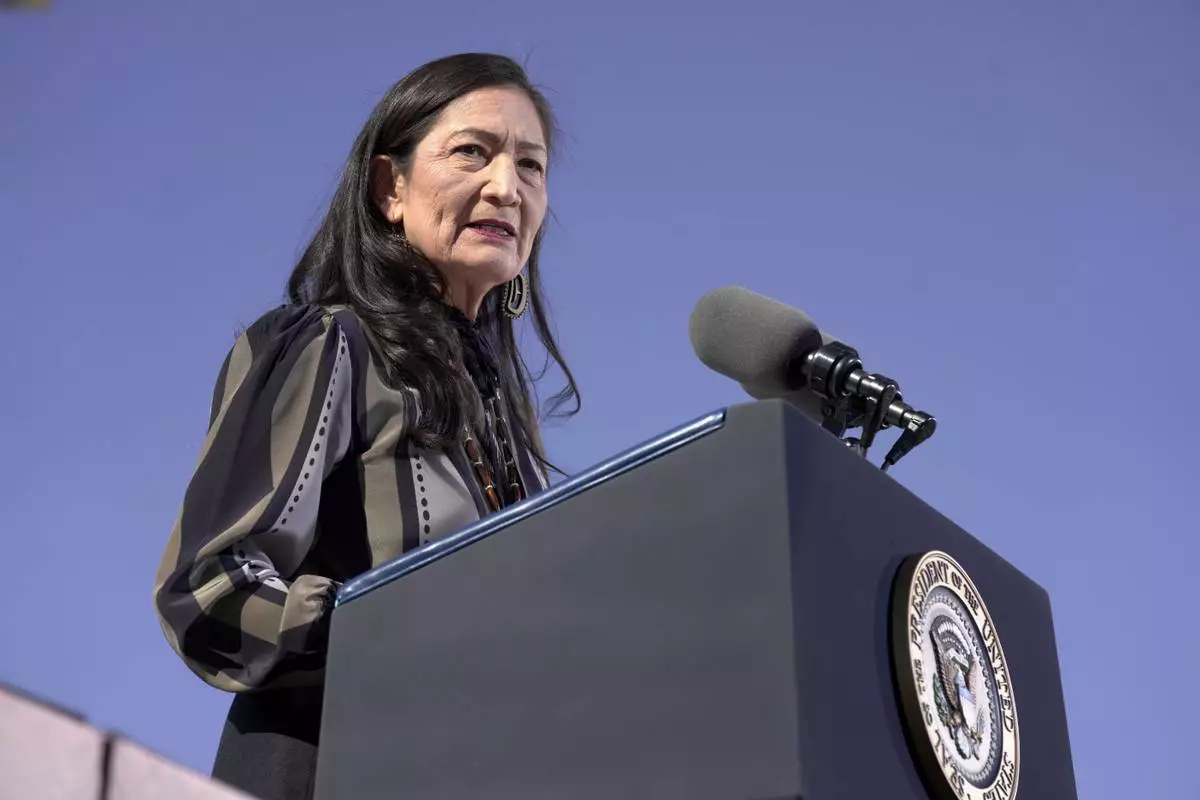

The schools were designed both to assimilate Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children and to dispossess tribal nations of their land, according to an Interior Department investigation launched by Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to lead the agency.

Introducing Biden on Friday, Haaland said that while the formal apology is an acknowledgement of a dark chapter, it is also a celebration of Indigenous resilience: “Despite everything that happened, we are still here.”

Haaland, a citizen of the Pueblo of Laguna, commissioned the investigation in 2021. It documented the cases of more than 18,000 Indigenous children, of whom 973 were killed. Both the report and independent researchers say the overall number was much higher.

The report came with several recommendations taken from the testimony of school survivors, including resources for mental health treatment and language revitalization programs.

Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis noted that Biden has pledged to make good on those recommendations.

“This lays the framework to address the boarding school policies of the past,” he said.

Benjamin Mallott, president of the Alaska Federation of Natives, who is Lingít, said in a statement that the apology must be accompanied by meaningful actions: “This includes revitalizing our languages and cultures and bringing home our Native children who have not yet been returned, so they can be laid to rest with their families and in their communities.”

That view is shared by Victoria Kitcheyan, chairwoman of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, which sued the U.S. Army in January seeking the return of the remains of two children who died at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania.

“That healing doesn’t start until tribes have a pathway to bring their children home to be laid to rest,” Kitcheyan said.

In an interview Thursday, Haaland said Interior is still working with several tribal nations to repatriate the remains of several children who were killed and buried at a boarding school.

Democratic U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who introduced a bill last year to establish a truth and healing commission to address the harms caused by the boarding school system, called the apology “a historic step toward long-overdue accountability for the harms done to Native children and their communities.”

And Sen. Lisa Murkowski, an Alaska Republican who is vice chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, also commended Biden while saying it reinforces the need for a truth and healing commission.

“This acknowledgement of the pain and injustices inflicted upon Indigenous communities — while long overdue — is an extremely important step toward healing,” Murkowski said in a statement.

As Biden spoke Friday, tribal members rose to their feet, with many recording the moment on their phones. Some wore traditional garments, and others had shirts supporting Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris.

There was a moment of silence, the formal apology and then an eruption of applause.

At the end of Biden’s remarks, the crowd stood again. There were shouts of, “Thank you, Joe.”

Hall, the boarding school survivor in Seattle, and others have long been advocating for resources to redress the harm. He worries that tribal nations will continue to struggle with healing unless the government steps up, and he sees a long road yet ahead.

“It took a lifetime to get here. It’s going to take a lifetime to get to the other side,” he said. “And that’s the very sad part of it. I won’t see it in my generation.”

Associated Press writer Matthew Brown in Billings, Montana, contributed to this report.

FILE - A poster about the history of Carlisle Indian Reform School includes a historical photo of Sioux girls upon arrival from their homes to the boarding school on Saturday, July 17, 2021 at the Sinte Gleska University Student Multicultural Center in Rosebud, S.D. (Erin Bormett/The Argus Leader via AP, File)

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland speaks at the Gila Crossing Community School in the Gila River Indian Community reservation in Laveen, Ariz., Friday, Oct. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

President Joe Biden speaks at the Gila Crossing Community School, Friday, Oct. 25, 2024, in Laveen, Ariz. (AP Photo/Rick Scuteri)

President Joe Biden, left, joined by Stephen Roe Lewis, Governor of the Gila River Indian Community, arrives to speak at the Gila Crossing Community School in the Gila River Indian Community reservation in Laveen, Ariz., Friday, Oct. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Attendees listen as Interior Secretary Deb Haaland speaks before President Joe Biden at the Gila Crossing Community School in the Gila River Indian Community reservation in Laveen, Ariz., Friday, Oct. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

President Joe Biden speaks at the Gila Crossing Community School, Friday, Oct. 25, 2024, in Laveen, Ariz. (AP Photo/Rick Scuteri)