CIUDAD HIDALGO, Mexico (AP) — The first place where many migrants sleep after entering Mexico from Guatemala is inside a large structure, a roof above and fenced-in sides on a rural ranch. They call it the “chicken coop” and they don’t get to leave until they pay the cartel that runs it.

Migrant encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border have reached a four-year low, but days before the U.S. election, in which immigration is a key issue, migrants continue pouring into Mexico.

Click to Gallery

Honduran migrants walk toward the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Eyla Fonseca feeds breakfast to her son Keilerth Veloz at the Casa del Migrante shelter in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Lisbeth Contreras hugs her children as she crosses the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Saturday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Luis Alonso Valle, center, sits in a car on his to Tapachula from Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, after crossing the Suchiate River with his family from Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Migrants rest in front of a paint shop in Tapachula, Mexico, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

City mayor, Elmer Vazquez, center, talks with workers in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, on the border with Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A Venezuelan migrant takes a selfie on a raft crossing the Suchiate River from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, to Mexico, Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Eyla Fonseca holds her son's hand during breakfast at the Casa del Migrante shelter in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Police officers patrol an area next to Suchiate River in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, on the border with Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrants cross the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Erika Arias waits with her family outside a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Elvin Cruz rests on a mat in a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Gerzon Zavala exchanges Guatemalan quetzales for Mexican pesos after crossing the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrants stand in line to have their photo taken by a smuggler as proof that they paid the passage fee to cross from Tecun Uman, Guatemala to Tapachula, Mexico, Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Mayra Torres hugs her sister in a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Salvadoran migrant Maria Garcia and her boyfriend cross the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

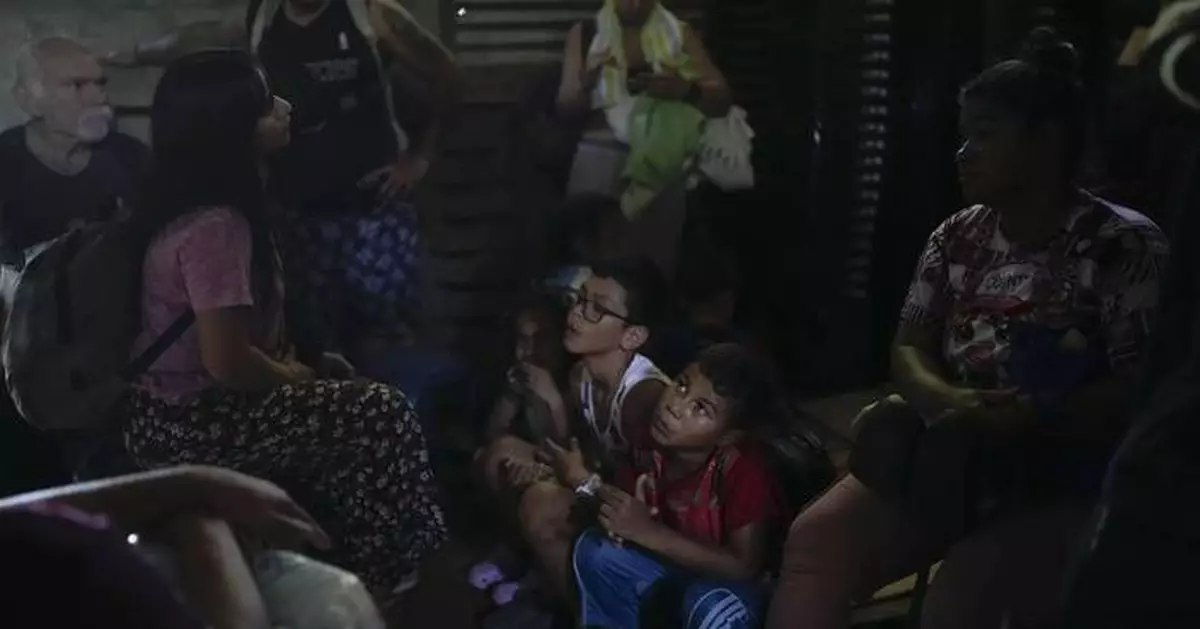

Venezuelan migrant Daniel Dura, second from right, waits next to his mother Rannely Duran inside a house before crossing the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

While U.S. authorities give much of the credit to their Mexican counterparts for stemming the flow to their shared border, organized crime maintains stricter control of who moves here than the handful of federal agents and National Guardsmen standing by the river.

Kidnapped migrants who pay the $100 ransom for their release are stamped to signal that they have paid. From January to August, just in this southernmost corner of Mexico, more than 150,000 migrants were intercepted by immigration agents, considered a fraction of the flow.

Six migrant families interviewed by The Associated Press, who had passed through an initial abduction and were held until paying, explained how it works. A Mexican federal official corroborated much of it. They all requested anonymity for fear of reprisals.

Mexican immigration agents encountered 925,000 undocumented migrants through August of this year, well above last year’s annual total and triple the 2021 total. Yet, they’ve only deported 16,500, a fraction of previous years.

Rev. Heyman Vázquez, a priest in Ciudad Hidalgo along the Suchiate river that divides Mexico and Guatemala, sees it daily.

“It’s them (the cartel) that says who passes and who doesn’t,” Vázquez said. “The numbers of migrants that they take every day are big and they do it in front of the authorities.”

On Monday morning, Luis Alonso Valle, a 43-year-old Honduran traveling with his wife and two children, climbed off a raft lashed together with truck inner tubes and boards that had carried them across the Suchiate to Mexico.

They hadn’t made it 50 yards toward Ciudad Hidalgo before three men approached on a motorcycle to tell them they couldn’t keep walking. Then seeing journalists they left. The family looked scared.

In Ciudad Hidalgo’s central plaza, Valle asked for a van that could take them the 23 miles (37 kilometers) to Tapachula, considered the main entry point for southern Mexico. Climbing aboard, the driver asked in a whisper that journalists stop recording. “They (organized crime) are going to stop me,” he said.

This is often how migrants arrive at the ranch. Taxi or van drivers working for the cartel take them there and hand them over. They’re forced to sleep on the ground.

“There were more than 500 people there, some had been there 10, 15 days,” said a Venezuelan woman who was released Sunday with her husband and two children. “Whoever doesn’t have money stays and whoever decides to pay leaves,” she said.

A 28-year-old baker from Ecuador was escorted to a bank to withdraw money to free himself, his wife, daughter and four other relatives. His family was held as insurance until he returned.

Once the payment is made, migrants' photos are taken and their skin stamped.

Gunmen stop vans and taxis headed to Tapachula and check for the stamps. Those without them are sent back. Migrants said that once they got to Tapachula they were told to wash them off to avoid trouble with other gangs.

According to the nongovernmental organization Fray Matias de Cordova in Tapachula, at least one-third of the hundreds of migrants they have attended to this year arrived stamped. Director Enrique Vidal Olascoaga said those who cannot pay are often sexually assaulted.

None of the families interviewed by AP said they had been harmed.

The official with knowledge of migrants' statements to investigators said that more than 100 migrants freed by security forces in Ciudad Hidalgo in September, as well as a group of several dozen migrants who were shot at by soldiers on Oct. 1, had passed through similar kidnapping and extortion scenarios.

Organized crime’s strict control at Mexico’s southern border tracks with the growing violence generated by the struggle between the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation cartels. The state of Chiapas is only one of their battlegrounds, but it is key to controlling smuggling routes for people, drugs and weapons from Central America. Migrants have become the most lucrative commodity, according to experts.

The cartels’ increasingly aggressive presence is becoming an obstacle to the organizations trying to help migrants. Earlier this month, gunmen killed an outspoken Catholic priest in Chiapas. And Vidal said that sometimes the groups prevent the migrants from receiving humanitarian aid.

President Claudia Sheinbaum has said the government is dealing with the violence, but refuses to confront the cartels. She appears to maintain tactics that began under the administration of former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, to cycle migrants from the north back down to the south exhausting their resources and keeping them far from the U.S. border — exposing them to more kidnappings and extortion.

Ciudad Hidalgo Mayor Elmer Vázquez claimed to not know anything about migrant safe houses operating in the area and said his town always looks after migrants.

But Rev. Vázquez (no relation to the mayor), who has spent two decades defending migrants, said the prosecutor’s office, National Guard, special prosecutor for crimes against migrants do nothing even when crimes are reported.

“They are colluding with organized crime and, of course, they make it look like they’re doing their jobs,” he said.

In August, the U.S. government expanded access to CBP One, an online portal used to schedule appointments to request asylum at the border, south to Chiapas. Mexico requested the move to relieve pressure migrants felt to travel north to get an appointment.

The Mexican government followed by opening “mobility corridors” to help migrants with CBP One appointments to travel safely from southern Mexico to the U.S. border. The appointments are just a first step, but most applicants are allowed to wait out the lengthy process from inside the U.S.

But from Sept. 9 to Oct. 11, Mexico’s National Immigration Institute said it had transported only 846 migrants from Tapachula to the northern border. Others traveling on their own have told of being extorted by Mexican authorities and kidnapped – again – by cartels near the northern border, forcing them to miss their appointments.

Donald Trump has said he would do away with CBP One and close other legal routes to enter the U.S.

In Tapachula on Tuesday, hundreds of migrants with confirmed CBP One appointments waited outside Mexican immigration agency offices for permits that would allow them to travel north.

Jeyson Uqueli, a 28-year-old Honduran, had slept outside the office to make sure he was the first in line when it opened. He was traveling alone, but planned to reunite with his sister in New Orleans.

To have any chance at doing so, he would have to make it to the border between Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico by Nov. 6 for his CBP One appointment. He planned to fly from Tapachula to the northern city of Monterrey and then take a bus to Matamoros.

He was nervous about making it in time, but relieved to have the appointment, “because Donald Trump is going to come in and get rid of (them),” he said.

AP journalists Matías Delacroix in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, and Edgar Clemente in Tapachula, Mexico, contributed to this report.

Honduran migrants walk toward the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Eyla Fonseca feeds breakfast to her son Keilerth Veloz at the Casa del Migrante shelter in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Lisbeth Contreras hugs her children as she crosses the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Saturday, Oct. 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Luis Alonso Valle, center, sits in a car on his to Tapachula from Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, after crossing the Suchiate River with his family from Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Migrants rest in front of a paint shop in Tapachula, Mexico, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

City mayor, Elmer Vazquez, center, talks with workers in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, on the border with Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

A Venezuelan migrant takes a selfie on a raft crossing the Suchiate River from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, to Mexico, Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Eyla Fonseca holds her son's hand during breakfast at the Casa del Migrante shelter in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Police officers patrol an area next to Suchiate River in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, on the border with Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrants cross the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Erika Arias waits with her family outside a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Elvin Cruz rests on a mat in a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Gerzon Zavala exchanges Guatemalan quetzales for Mexican pesos after crossing the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrants stand in line to have their photo taken by a smuggler as proof that they paid the passage fee to cross from Tecun Uman, Guatemala to Tapachula, Mexico, Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Honduran migrant Mayra Torres hugs her sister in a shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Salvadoran migrant Maria Garcia and her boyfriend cross the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Monday, Oct. 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

Venezuelan migrant Daniel Dura, second from right, waits next to his mother Rannely Duran inside a house before crossing the Suchiate River, which marks the border between Guatemala and Mexico, from Tecun Uman, Guatemala, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Matias Delacroix)

JERUSALEM (AP) — Israeli legislation cutting ties with the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees raised fears that the largest provider of aid to Gaza could be shut out of the war-ravaged territory, even as the implications of the new laws remained unclear Tuesday.

The agency known as UNRWA provides essential services to millions of Palestinians across the Middle East and has underpinned aid efforts in Gaza throughout the Israel-Hamas war. Legislation barring it from operating in Israel passed with an overwhelming majority Monday. Israel says UNRWA has allowed itself to be infiltrated by Hamas, with the militants siphoning off aid and using the agency’s facilities as shields. UNRWA denies the allegations, saying it is committed to neutrality and acts quickly to address any wrongdoing by its staff.

The two newly passed laws are all but certain to hamper UNRWA's work in Gaza and the occupied West Bank, as Israel controls access to both territories. But the details of how the legislation would be implemented, and potential workarounds, remain unclear. It could also face legal challenges.

Either way, the laws could have major consequences for Palestinians in Gaza, who are heavily reliant on emergency food aid more than a year into a war that has killed tens of thousands, according to local officials who don't distinguish combatants from civilians; displaced 90% of the population of 2.3 million; and left much of the territory in ruins.

The first law prohibits UNRWA from “operating any mission, providing any service or conducting any activity, either directly or indirectly, within Israel’s sovereign territory,” according to a statement from parliament.

It's unclear whether UNRWA would still be able to operate inside Gaza and the West Bank, territories Israel captured in the 1967 Mideast war but has never formally annexed. The Palestinians want both to be part of a future state.

The second law prohibits Israeli state agencies from communicating with UNRWA and revokes an agreement dating to 1947, before Israel was created, under which it facilitated UNRWA’s work.

With Israel controlling all access to Gaza and the West Bank, it could be difficult for UNRWA staff to enter and leave the territories through Israeli checkpoints, and to bring in vital supplies for its schools, health centers and humanitarian programs.

UNRWA and its staff would also lose their tax exemptions and legal immunities.

UNRWA’s headquarters are in east Jerusalem, which Israel seized in the 1967 war and annexed in a move not recognized internationally.

Much of the agency’s supply lines to the territories run through Israel, and shutting them down could create even more obstacles to getting essential aid — everything from flour and canned vegetables to winter blankets and mattresses — into Gaza.

At present, all shipments of aid into Gaza must be coordinated with COGAT, the Israeli military body in charge of civilian affairs, which inspects all shipments. Aid groups say their work is already hampered by Israeli delays, ongoing fighting and the breakdown of law and order inside Gaza.

Aid levels plunged in the first half of October as Israel closed crossings into north Gaza, where hunger experts say the threat of starvation is most acute. COGAT attributed the decline to closures related to the Jewish holidays and troop movements for a large, ongoing offensive in northern Gaza.

In the first 19 days of October, the U.N. says, 704 trucks of aid entered the Gaza Strip, down from over 3,018 trucks in September and August. COGAT’s own tracking dashboard shows aid deliveries in October plunging to under a third of their September and August levels.

The new laws would also likely bar UNRWA from banking in Israel, raising questions about how it would continue to pay thousands of Palestinian staff in Gaza and the West Bank. Its international staff would likely have to relocate to third countries like Jordan.

Rights groups say Israel is obliged under international law to provide for the basic needs of people in the territories it occupies. Israel also faces increasing pressure from the Biden administration, which says it may have to reduce U.S. military support if there isn’t a dramatic increase in aid going into Gaza.

State Department spokesman Matthew Miller said the United States was “deeply troubled” by the legislation, which “poses risks for millions of Palestinians who rely on UNRWA for essential services.”

“We are going to engage with the government of Israel in the days ahead about how they plan to implement it” and see whether there are any legal challenges, he said.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said in a statement Monday that Israel is“ready to work with our international partners to ensure Israel continues to facilitate humanitarian aid to civilians in Gaza in a way that does not threaten Israel’s security.”

But many of those partners insist there is no alternative to UNRWA.

A spokesperson for the U.N. children’s agency, which also provides aid to Gaza, denounced the new laws in unusually strong language, saying "a new way has been found to kill children.”

James Elder said the loss of UNRWA “would likely see the collapse of the humanitarian system in Gaza.” His agency, known as UNICEF, “would become effectively unable to distribute lifesaving supplies,” such as vaccines, winter clothes, water and food to combat malnutrition.

Israeli officials are considering the possibility of having the military or private contractors take over aid distribution, but have yet to develop a concrete plan, according to two officials who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the closed-door discussions.

COGAT referred all questions on the new legislation to the government.

At risk is not just UNRWA’s aid delivery to Gaza, where it is also the largest employer. UNRWA also operates schools in the occupied West Bank serving over 330,000 children, as well as health care centers and infrastructure projects.

Amy Pope — head of the International Organization for Migration, another U.N. body — said it would not be able to fill the gap left by UNRWA, which she described as “absolutely essential.”

“They provide education. They provide health care. They provide some of the most basic needs, for people who have been living there for decades,” she said.

FILE - Displaced Palestinians inspect their tents destroyed by Israel's bombardment, adjunct to an UNRWA facility west of Rafah city, Gaza Strip, Tuesday, May 28, 2024. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi, File)

FILE - United Nations and Red Crescent workers prepare the aid for distribution to Palestinians at UNRWA warehouse in Deir Al-Balah, Gaza Strip, on Monday, Oct. 23, 2023. (AP Photo/Hassan Eslaiah, File)

FILE - Israeli soldiers take position as they enter the UNRWA headquarter where the military discovered tunnels underneath of the U.N. agency that the military says Hamas militants used to attack its forces during a ground operation in Gaza, Thursday, Feb. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit, File)

FILE - Palestinians look at the destruction after an Israeli strike on a school run by UNRWA, the U.N. agency helping Palestinian refugees, in Nuseirat, Gaza Strip, May 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana, File)

FILE - Palestinians check the bodies of their relatives killed in an Israeli bombardment of UNRWA school at Nusseirat refugee camp, in front of the morgue of al-Aqsa Martyrs hospital in Deir al-Balah, central Gaza Strip, early Thursday, June 6, 2024. (AP Photo/Abdel Kareem Hana, File)

An ultra-Orthodox Jewish man walks past the east Jerusalem compound of UNRWA, the U.N. agency helping Palestinian refugees, Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Mahmoud Illean)

FILE - Palestinian children who fled with their parents from their houses in the Palestinian refugee camp of Ein el-Hilweh, gather in the backyard of an UNRWA school, in Sidon, Lebanon, Sept. 12, 2023. (AP Photo/Mohammed Zaatari, File)