As part of a sweeping two-year investigation into prison labor, The Associated Press found that correctional staff nationwide have been accused of using inmate work assignments to sexually abuse incarcerated women, luring them to isolated spots, out of view of security cameras. Many cases follow a similar pattern: Accusers are retaliated against, while the accused face little or no punishment.

Here are takeaways from the AP’s investigation:

Though they represent only 10% of the nation’s overall prison population, female incarceration rates have jumped from about 26,000 in 1980 to nearly 200,000 today. Most women have been locked up for nonviolent crimes that often are drug related.

In all 50 states, reporters found cases where women said they were attacked by staff while doing jobs like kitchen or laundry duty inside correctional facilities or in work-release programs that placed them at private businesses such as national fast-food restaurants and hotel chains.

Accused correctional staff often quit or retire before internal investigations are complete, sometimes retaining pensions and other benefits, experts say. With no paper trail and severe staff shortages nationwide, some are simply transferred or hired at other facilities or they land positions overseeing vulnerable populations like juveniles. Even when allegations do lead to criminal charges, convictions can be rare, which also makes it possible for perpetrators to avoid placement on sex offender registries.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act, passed more than two decades ago, created a channel for filing reports that resulted in a threefold increase in the number of allegations of staff sexual misconduct involving male, female and transgender inmates from 2010 to 2020 at jails and prisons nationwide.

Internationally, prison rape is recognized as a form of torture. In some states, correctional officers argue that — despite the clear power imbalance — inmates gave their consent. Laws vary from state to state. For example, sexual abuse of an inmate can be a misdemeanor in Kentucky, with a maximum sentence of 12 months, but prison rape is a felony in Pennsylvania, carrying up to seven years behind bars.

In cases that were confirmed through internal investigations nationwide, less than 6% of the nearly 1,000 staff who reportedly engaged in sexual misconduct with male and female inmates in 2019 and 2020 were prosecuted, according to the latest Department of Justice figures.

Brandy Moore White, head of the union representing 30,000 correctional staff in federal prisons, said chronic worker shortages are part of the problem, noting that staff are also vulnerable to abuse by inmates. “If you have 10 staff supervising 500 inmates,” she said, “there is time for people who have ill intentions to do things that they shouldn’t do.”

Women have been targeted from their days on slave plantations, when they were raped by their owners, to the decades-long period that followed emancipation and involved leasing convicts out to private companies. Widespread reports of sexual abuse eventually led to the creation of reformatories, where women no longer were overseen by men. That began to change in the 1970s as anti-discrimination laws opened the door for cross-gender supervision, just as the number of women being locked up started to rise.

Most female victims were abused before being incarcerated, research shows. They rarely report assaults, fearing they won’t be believed or will be punished, ranging from losing their jobs to being placed in solitary confinement or denied contact with their children. And many on work release have only a short time left to serve and are wary of doing anything that could send them back to prison or add time to their sentences.

Some guards believe women with substance abuse issues are accustomed to using sex as a commodity on the streets, seeing them as partly responsible for their own victimization, said Brenda Smith, a law professor at American University and one of the country’s top experts on prison rape. “They’re viewed as sort of the lowest of the low,” she said. “They’re not really women — they’re just other things.”

As part of the AP’s investigation — which has exposed everything from multinational companies benefiting from prison labor to incarcerated workers’ lack of rights and protections — reporters spoke to more than 100 current and former prisoners nationwide, including women who said they were sexually abused by correctional staff.

Reporters also scoured thousands of pages of court filings, police reports, audits and other documents that detailed graphic stories of systemic sexual violence and coverups from New York to Florida to California.

Those cases prompted a bipartisan Senate investigation two years ago that found prisoners were sexually abused by wardens, guards, chaplains or other staff in at least two-thirds of all women’s federal prisons over the past decade. And just last month, U.S. lawmakers held a hearing to discuss how to better safeguard inmates.

The Associated Press receives support from the Public Welfare Foundation for reporting focused on criminal justice. This story also was supported by Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights in conjunction with Arnold Ventures. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

——

Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org or https://www.ap.org/tips/

The courtyard outside the Cabell County Courthouse sits empty after hours, Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2024, in Huntington, W. Va. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

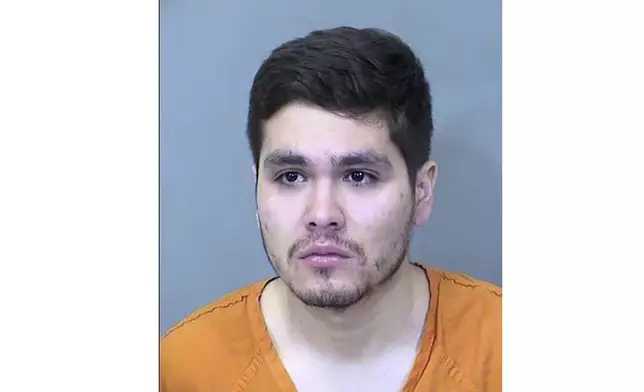

This September 2023 booking photo, provided by the Maricopa County Sheriff's Office, shows Jose Figueroa-Lizarraga, a former Arizona state prison guard who was sentenced to two years probation after pleading guilty to a lesser charge of committing unlawful sexual acts by a custodian. (Maricopa County Sheriff's Office via AP)

FILE - Two men walk into the Federal Correctional Institution in Dublin, Calif., Monday, April 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Terry Chea, File)

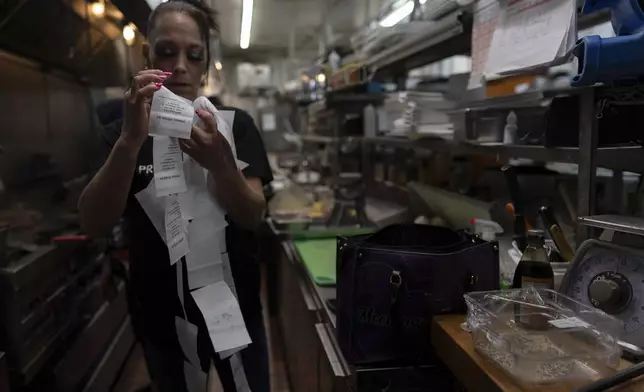

April Youst enters the kitchen of a restaurant where she works, Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2024, in West Virginia. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

April Youst goes through dinner orders in the kitchen while working at a restaurant in West Virginia on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

April Youst pauses for a cigarette in her backyard in West Virginia on Wednesday, Oct. 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)